On Antiracism, Resisting Fascism, and Policing in London

Chris Steele-Perkins and Peter Marlow documented a 1977 protest in South East London which defined British race relations of the time

Magnum Photographers

The day had started with a peaceful gathering of anti-racism campaigners near Ladywell station in South East London. However, by 2pm on August 13th, 1977 – 43 years ago today – there was chaos. Members of the far right group the National Front, counter-protestors and police clashed in what would come to be known as the Battle of Lewisham.

Even before the event, there had been concerns about violence. The National Front’s plan to march had been denounced in a letter to The Times as “a direct incitement to racial hatred” and the day before it would take place a letter, published also in The Times, warned that it would be “naive to presume that there will be no violence.” Chris Steele-Perkins, who arrived around noon to photograph the march, considers why there was such an urge to document and to resist: “Everybody expected it,” he says, “The idea that fascists would be walking the streets of London without some without some kind of confrontational response seemed fairly self-evident.”

Social tension had been brewing for a while. Almost a year earlier, London’s largest Afro-Carribean-led street party, the Notting Hill Carnival, had ended in riots. The Battle of Wood Green, between the National Front and members of the local community in the North London borough of Haringey, had occurred in April. The National Front and affiliated far-right groups were striving for political legitimacy and seemed to be getting it with significant percentages of votes in London council elections. In a May 1977 Lewisham by-election, they came fourth.

"The idea that fascists would be walking the streets of London without some without some kind of confrontational response seemed fairly self-evident."

- Chris Steele-Perkins

Events in in May 1977 also fed into the clashes on the 13th with 21 black people from Lewisham having been arrested on suspicion of involvement in a recent spate of muggings. In response to the heavy-handed arrests, members of the community set up the Lewisham 21 Defence Committee who held a protest in July. 200 members of the National Front came out to meet them, hurling rotten fruit and caustic soda. The right-wing group then announced that it would be holding its own “anti-mugging” march through New Cross and Lewisham on the 13th of August.

"Social tension had been brewing for a while. Almost a year earlier, London’s largest Afro-Carribean-led street party, the Notting Hill Carnival, had ended in riots."

-

The counter-protesters, who would in the event outnumber the National Front by thousands, consisted of a coalition of local community members and left-wing groups. The All Lewisham Campaign against Racism and Fascism (ALCARAF), the Anti-Racist / Anti-Fascist Co-ordinating Committee (ARAFCC) and the recently formed Socialist Workers Party came out in force to denounce the National Front alongside religious leaders like the Bishop of Southwark Mervyn Stockwood and civil rights campaigner and former British Black Panther Darcus Howe.

Desperate to keep the two groups from ever meeting, the Metropolitan police – generally referred to in London as the Met – diverted the counter-protesters’ route. In spite of these efforts many slipped away through the backstreets intent on physically blocking the National Front’s progress through the main roads. Steele-Perkins said “I do remember going up towards a side street off New Cross. There was a crowd of people outside the pub and I thought maybe I could get a quick drink before it all kicks off. But as I got a bit closer, I realized it was National Front supporters… not people I wanted to be hanging around with. But they were getting tanked up before the confrontation as it were.”

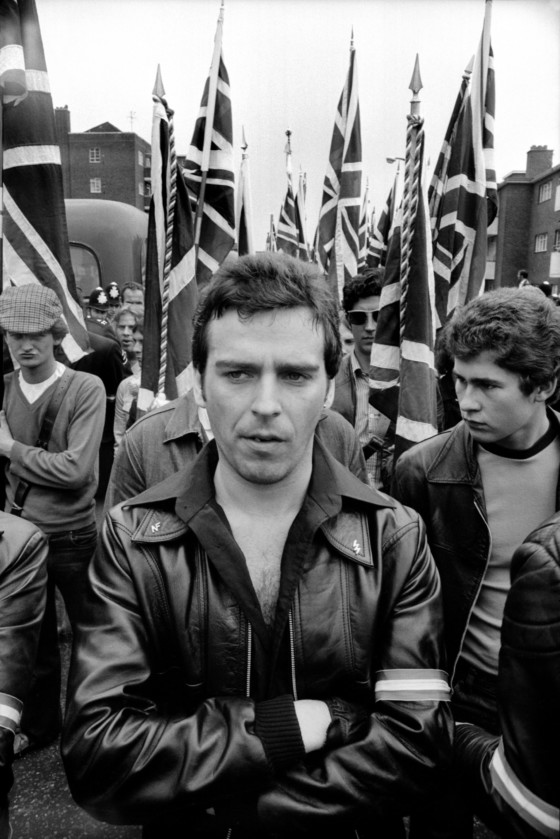

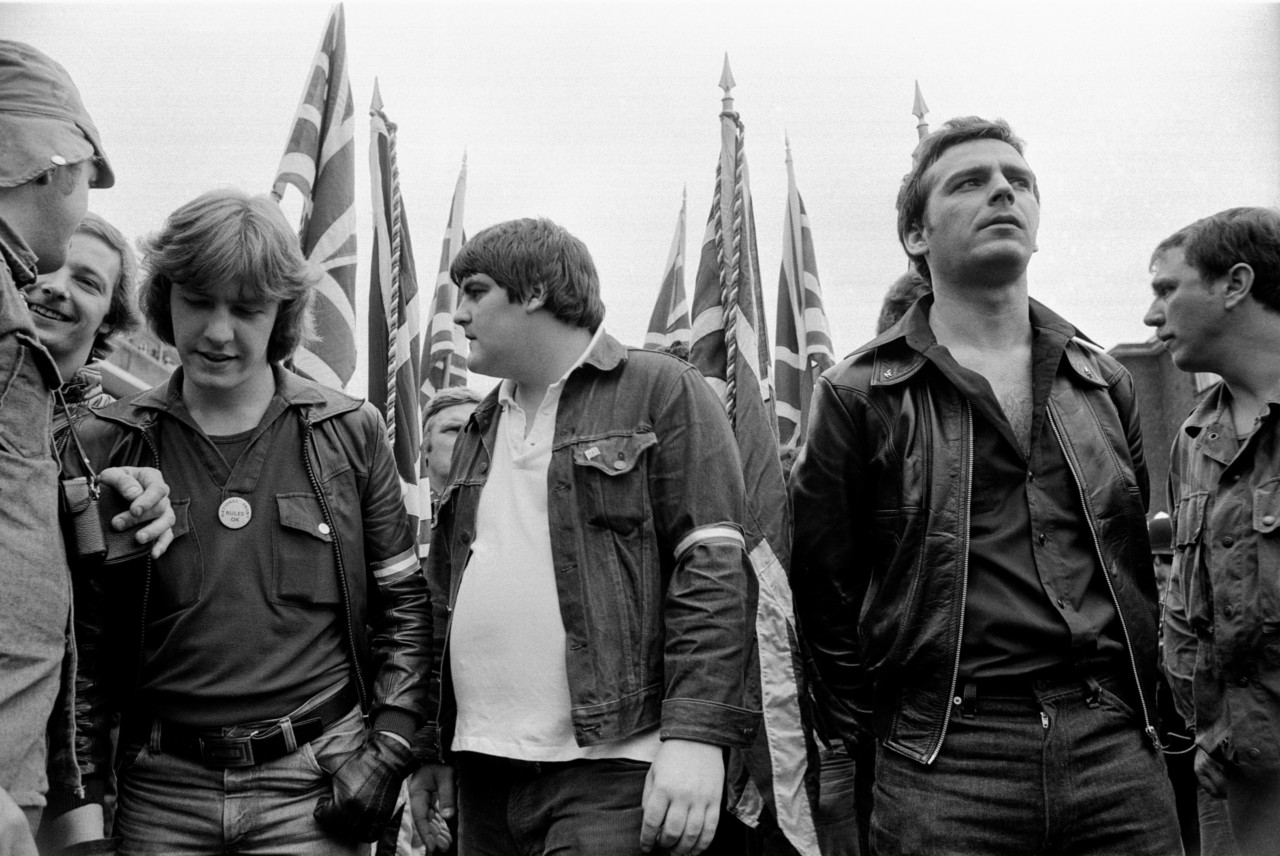

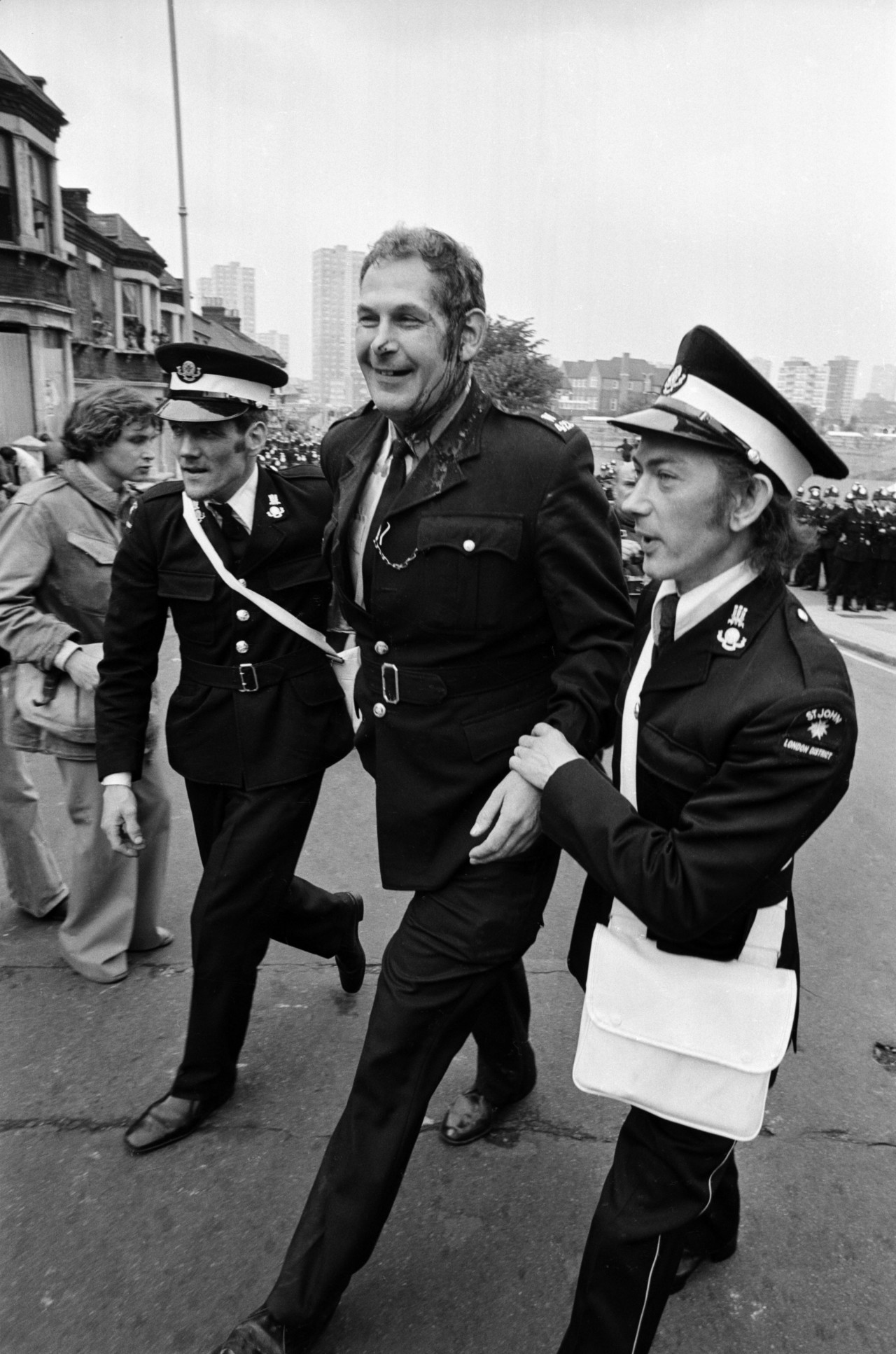

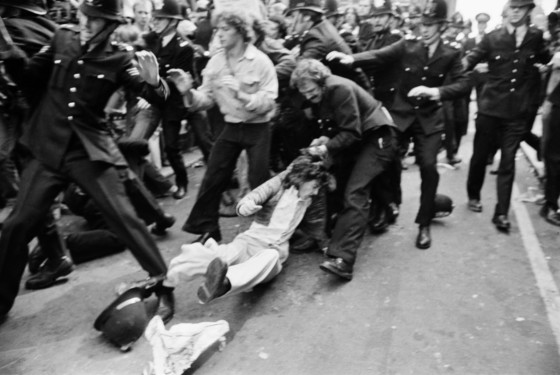

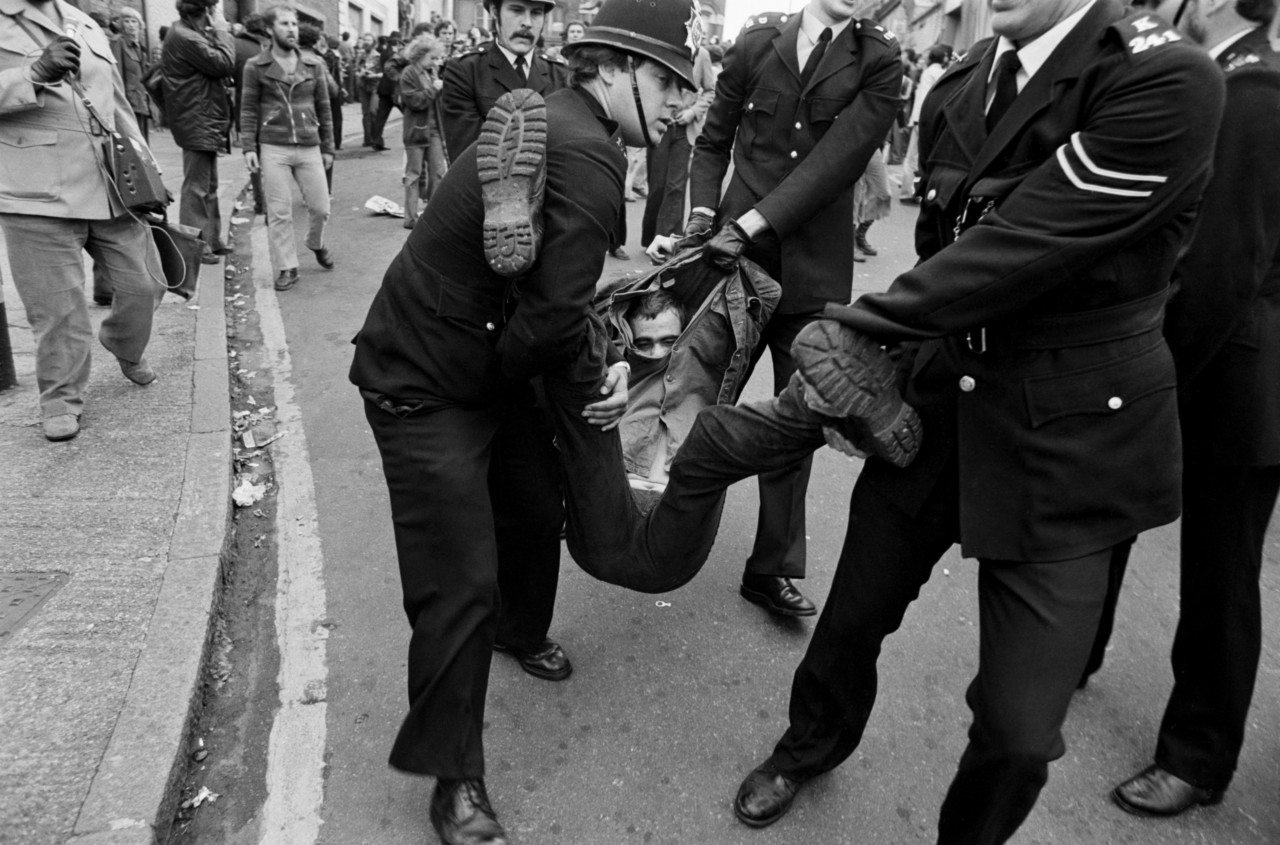

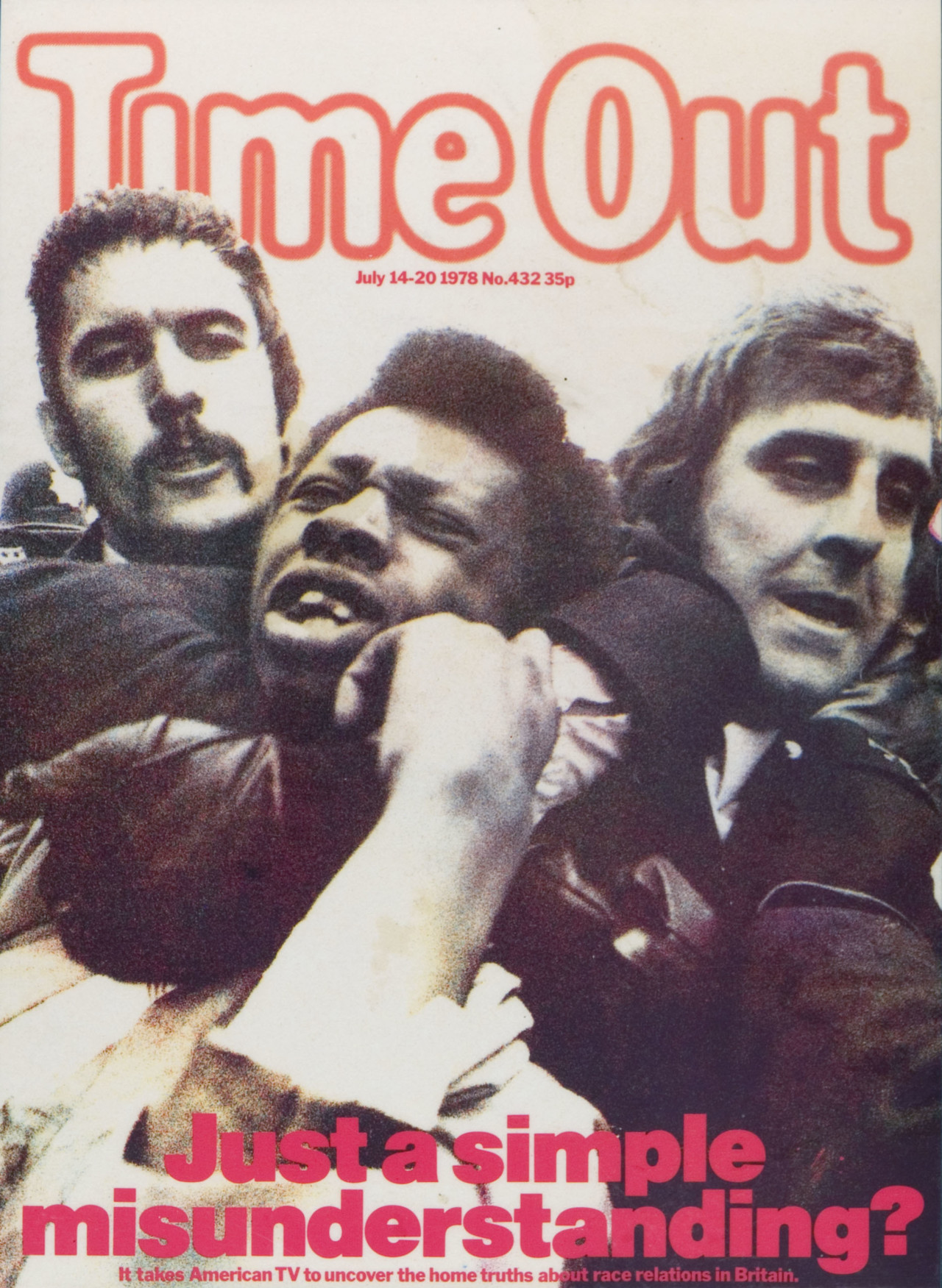

The main skirmishes began as the police attempted to forcibly clear the route. Large crowds had gathered on Clifton Rise and were being contained — partly to prevent them spilling out into Achilles Street where the National Front were gathering, but also to keep them from getting down to New Cross Road where they might block the march route. The counter-protestors, National Front members and police clashed as the march moved onto the main road and people broke through police lines. Bottles and bricks were hurled, flags were captured and burned. Peter Marlow was another Magnum photographer who captured the tumult. A few of his images depict members of the National Front and anti-racist protestors physically fighting, the slight blurring of their forms conveying a degree of the commotion.

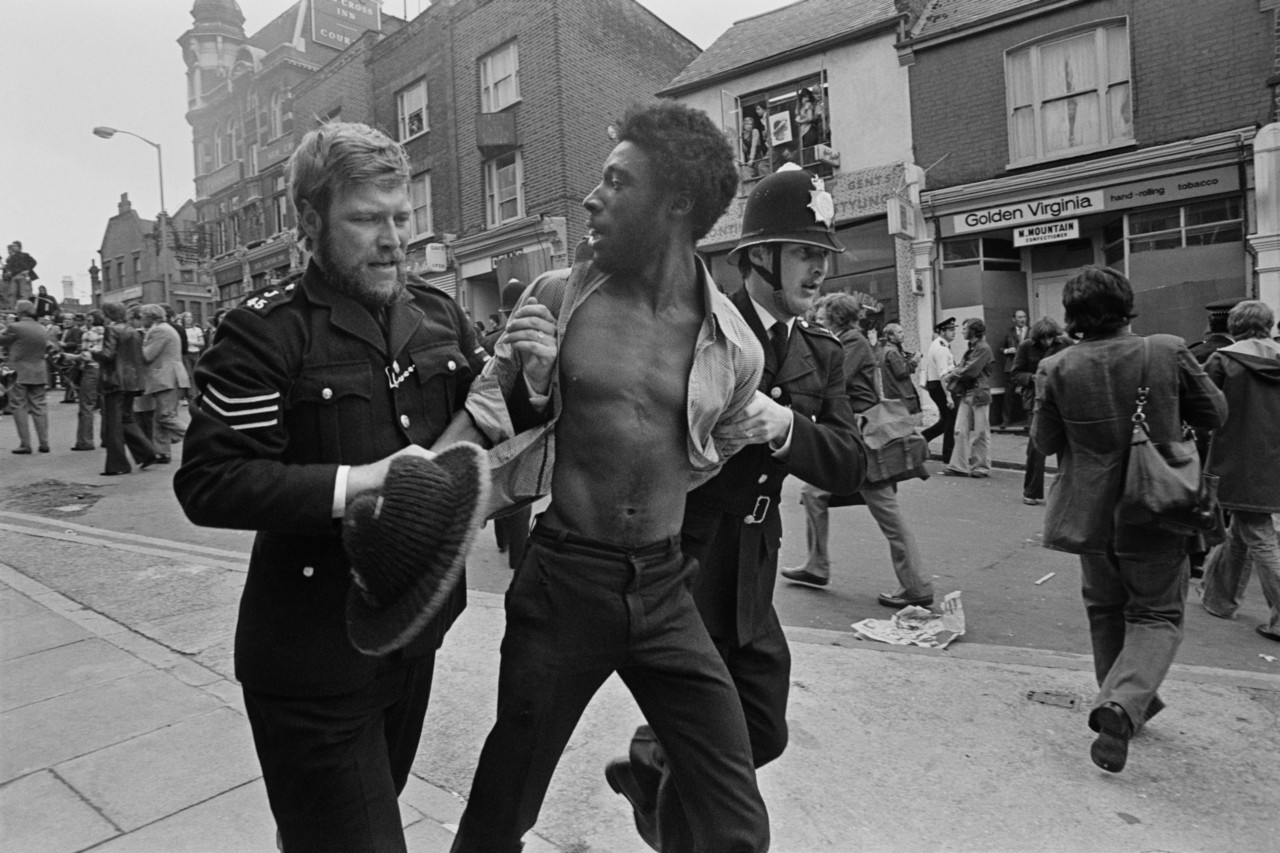

These photographs will look familiar to anyone who has seen images of protests, riots and fascist-antifascist confrontations that have taken place in the decades since the Battle of Lewisham. Union flags, mounted officers, smoke bombs, banners, placards and a heavy police presence abound in the images. Police feature prominently in both Marlow and Steele-Perkins’ photos which emphasize not just the sheer numbers of the Met officers on the streets (estimated to be 5000) but also the tactics used to police the march, which included the first ever use of riot shields by British forces on home turf (in Northern Ireland the equipment had been in use for almost a decade).

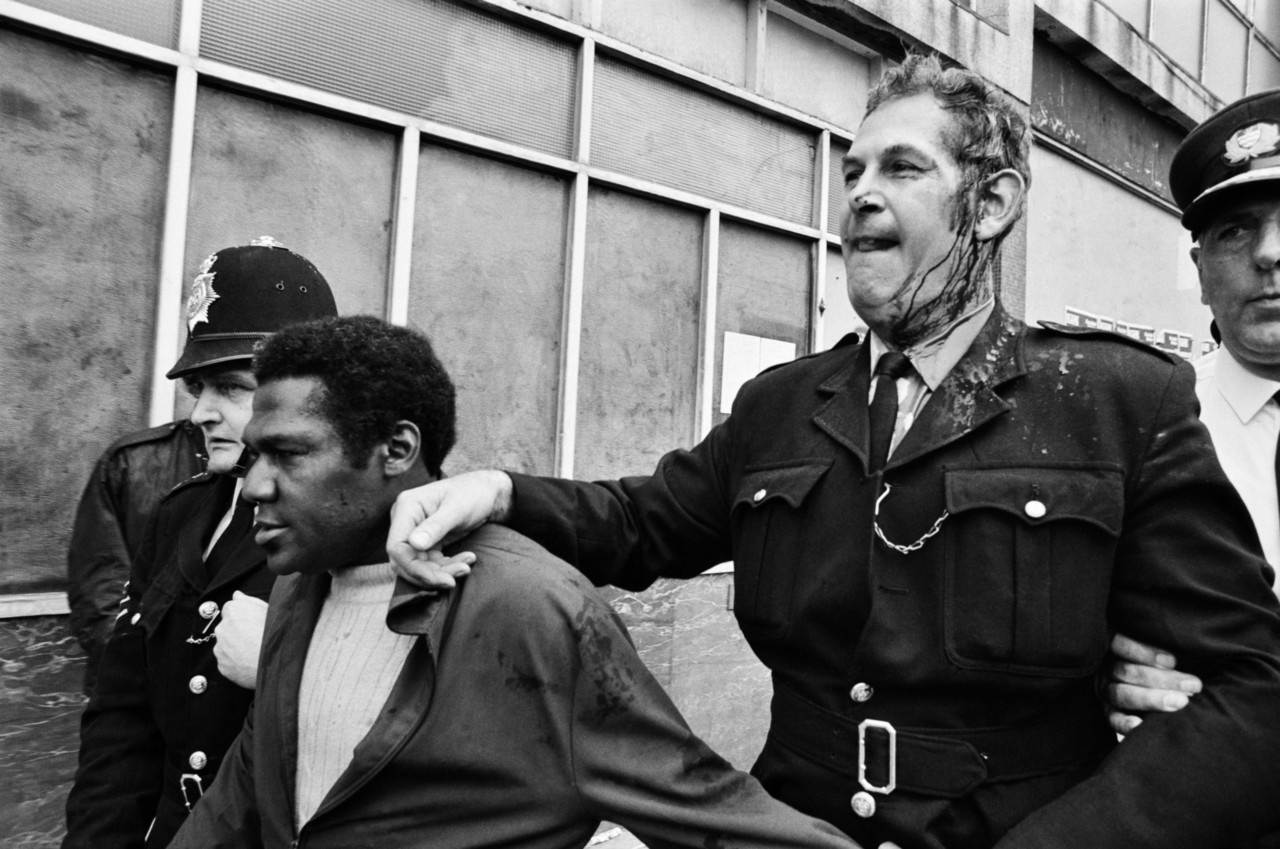

“The police were there to control the crowd and to maintain law and order,” says Steele-Perkins. “It did seem to me that they were facilitating something unacceptable: the march of fascists in a free London. And it seemed like they were picking on black people a lot too.” Both photographers took images depicting black protestors being held in chokeholds by officers, with Marlow’s appearing on the cover of Time Out magazine the following year.

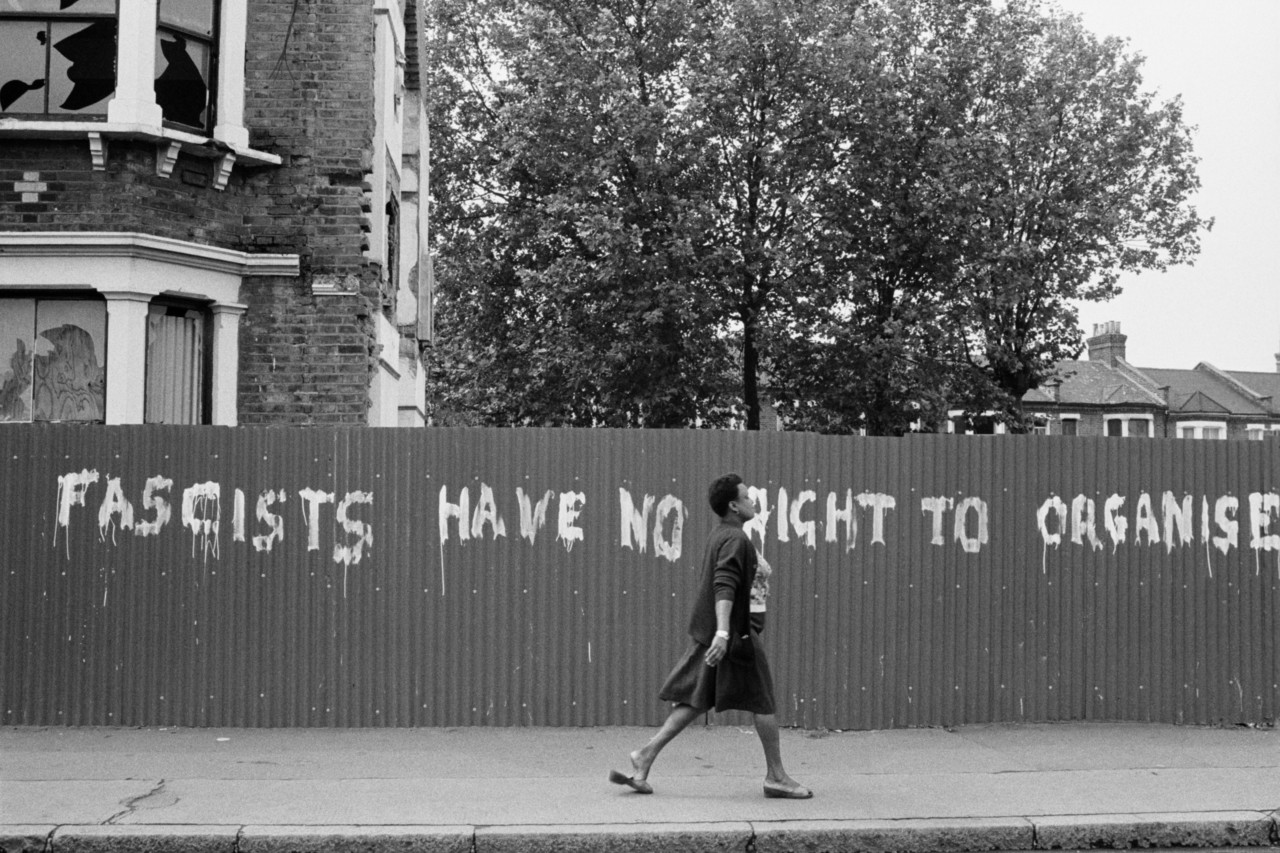

The use of excessive force by British police officers particularly in their contact with black people has been a topic of discussion and cause for protest for decades. It has risen again to the fore now in the wake of the death of George Floyd in America, and the Black Lives Matter protests which are forcing a national conversation on systemic racism in Britain.

As for the presence of the far right, the Battle of Lewisham would eventually be considered the death knell for the National Front and its affiliates being taken seriously— at least as political forces. At the time it was difficult to “see it as a watershed” rather than simply one of many street clashes, says Steele-Perkins. Confrontations between fascist and anti-fascist groups and police would also flare up around the city and country-wide in the 1980s, but this event would always be deemed significant for being the first occasion on which the National Front were stopped from marching along their planned route.

"It did seem to me that they were facilitating something unacceptable: the march of fascists in a free London."

- Chris Steele-Perkins

The Battle of Lewisham is now commemorated in a mural in New Cross that attests to that significance despite the event’s relatively muted legacy in comparison, for example, to the 1936 Battle of Cable Street. What is intriguing about the mural is that by taking its inspiration from 1970s zines, instead of focusing on wholly original painted or illustrated images, striking photographs from the day have been adapted and incorporated into this public artwork.

Marlow’s image of the Metropolitan Police officers behind riot shields appears as does Steele-Perkins’ photo of a black protester held in a chokehold by a police officer. A well-known image of Darcus Howe by Syd Shelton also appears. The mural was not created until 2019, and, together with the maroon plaque unveiled on the event’s 40th anniversary in 2017, is a long-awaited commemoration of a moment that contributed to the diminishing of far-right political power in the ‘70s and ‘80s. The mural is also a testament to the power of photography to create iconic images that can embody and reanimate a historical event for later generations.