Human Rights at Home: Documenting the Plight of Canada’s First Nations

Larry Towell visited the Attawapiskat First Nation in Ontario to photograph the housing crisis facing the isolated community

Seventy years ago, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a milestone document that “proclaimed the inalienable rights which everyone is inherently entitled to as a human being”. To mark this, a new theme called ‘Human Rights at Home’ reflects on the work of three Magnum photographers who have reported on injustices in their country of birth. All have worked on such issues extensively around the world – but how difficult is it to turn one’s gaze inwards and examine the flaws that exist in your own ‘backyard’?

Larry Towell’s interest in the plight of North America’s First Nations reflects a lifelong advocacy of human rights. “I started photographing in Central America during the Reagan years and worked in the Middle East and in other places of social unrest,” says the Canadian photographer. “So looking internally, looking in my own home, only makes sense.”

A concern for the indigenous people of his home country has long been held, but it wasn’t until 2013 that his documentation began in earnest. “You’re often drawn to issues when they boil to the surface,” says Towell. “I’ve always been interested in First Nation issues but I’d never had any doors in until the [resistance movement] Idle No More and then things began to boil over—even in my own backyard.”

A few miles from Towell’s home in Ontario, the Aamjiwnaang First Nation in Sarnia had camped across a railway track, blocking a spur line for CN rail. Their lands are within a 25 km radius of 60 industrial facilities—many of them chemical—packed within a 15-square-mile area known as Chemical Valley. “The trains were carrying chemicals into Chemical Valley for oil processing and plastics – they stopped the trains for about ten days or so,” says Towell, who photographed the resistance.

Towell then visited Attawapiskat First Nation in northern Ontario to report on its dire housing conditions, which had triggered a State of Emergency (meaning federal resources and funds are galvanised) and a humanitarian intervention by the Red Cross a year before. The lack of governmental action since then had lead Chief Theresa Spence to go on hunger strike, drawing attention to the poor state of infrastructure in First Nation settlements countrywide. Her hunger strike became synonymous with Idle No More, an indigenous resistance movement that was sweeping the country at that time. “All of a sudden there was quite a lot of attention on First Nation issues really for the first time in Canada – it’s always been on the back burner but now it was on the front burner,” says Towell.

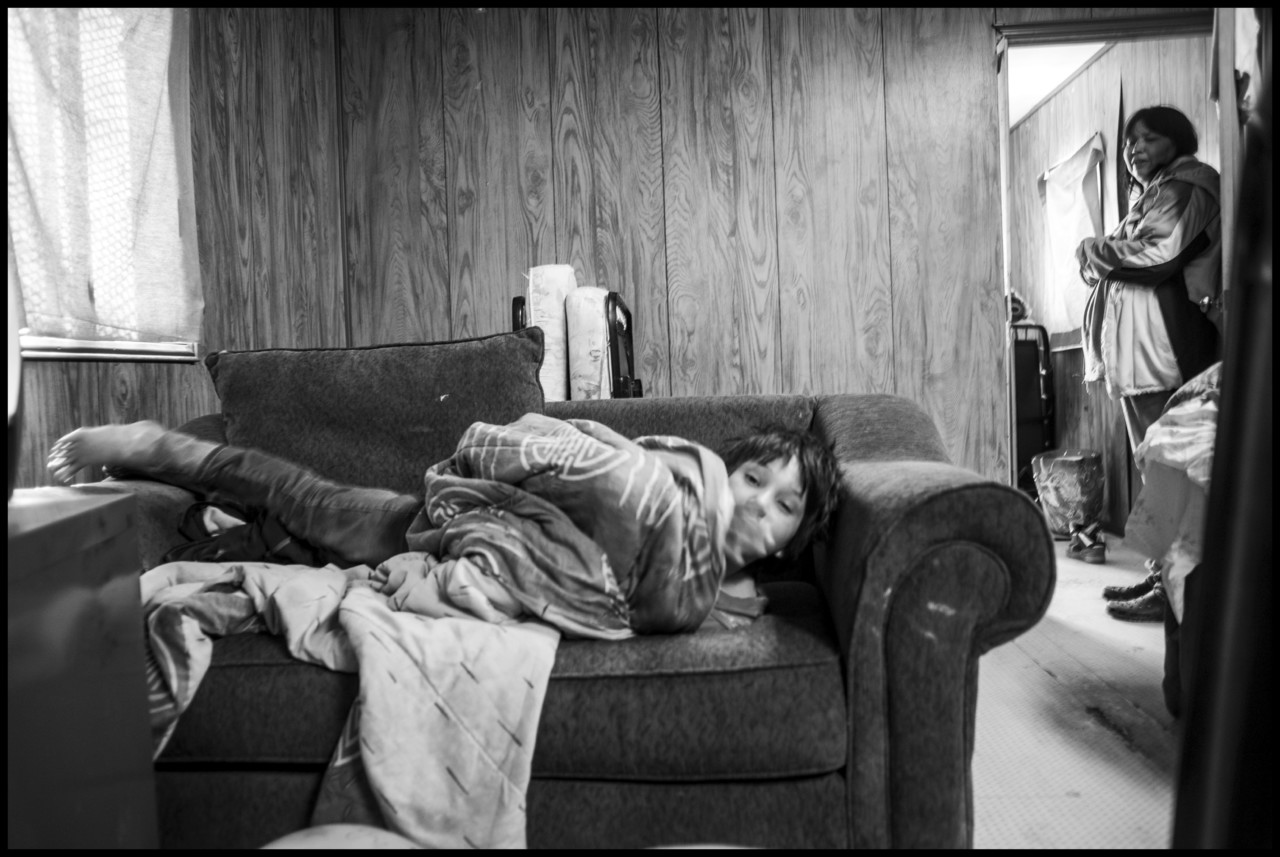

His photographs of the isolated Attawapiskat—accessible only by one road in summer and by airplane in the winter—show a community suffering the indignity of temporary housing as a long-term solution. “Most of the houses were trailers that were brought in and were sitting on bog and began to sink,” he says. “There’s not enough housing so a lot of people chose to live in these one room garages—sheds that were originally garages for snowmobiles—rather than the used, cast-off office buildings that are more communal.” At the time of the State of Emergency, five families were living in non-insulated tents, 19 families were living in makeshift sheds without water or electricity, 87 buildings fit for condemnation were being used as homes for 128 families and 35 families living in houses needing serious repair.

But poor housing is just one of many issues this community endures. Indeed Attawapiskat has long been a bellwether for the crisis affecting First Nation populations across Canada, such as scant access to good education, healthcare and clean water. In April 2016, a rash of suicide attempts—eleven people tried to take their own life in one night alone—threw a spotlight on the poor mental health of similar communities in the country.

“This didn’t shock me,” says Towell. “Every few years there are States of Emergency in many of these communities – including Pine Ridge.” Towell’s work on Pine Ridge, a Sioux reservation in South Dakota, shows a similar story of poverty, poor housing and high rates of depression and suicide. Towell attributes this to a painful history of oppression throughout North America. “First Nations people have an identity crisis thrust upon them by colonial history,” says Towell. “They were here first and displaced and it has been very difficult for them to rise above this current situation I think.”

But things are gradually changing. Idle No More quickly became one of the largest Indigenous mass movements in Canadian history. Meanwhile this Spring, Towell photographed protests against the controversial extension of the Kinder Morgan pipeline. The protests—led by First Nations in British Columbia, who see its expansion as an infringement of their sovereign rights—were the largest the country had ever seen. This wave of indigenous resistance, which seems to only be growing, is reflected in Towell’s shift in focus. “Change doesn’t happen quickly; it will take generations. But I’m interested in how people are rectifying problems themselves,” says Towell. “I have become more interested in resistance than poverty.”