The Everyday and the Extreme: The Far Right in the USA through the Magnum Archive

Magnum photographers reflect on their experiences photographing racist movements in America, and finding sinister beliefs thriving in the most ordinary of contexts

This is the second in a two-part series looking at far right movements and their supporters through the Magnum archive. The first focuses on the far right in the United Kingdom — read it here.

In 1990, when Carl de Keyzer wanted to photograph the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) setting a cross on fire, he had to phone Klan leader Thomas Robb in person. “The Klan was not very popular then, and these cross lightings did not happen very often,” he says. “Finally, one month before we went back to Belgium, I called him again. He didn’t remember me but said: ‘If you’re white, you can come’.”

In 2001, over a decade later, Jonas Bendiksen had a similar experience shooting a neo-Nazi family festival in Kentucky called NordicFest. A young photographer shooting ‘identity’ for a World Press Photo masterclass, he wanted to see the event because “the idea of it was so bizarre to me”. “I just cropped my hair short, bought a tent, and hoped they would love my Norwegian accent,” he says. As he suspected, they did, and welcomed him into the event which was “hidden away in a forest”.

These sorts of offbeat recollections seem common among photographers covering the fringes of the far right, whether on assignment or as part of extensive personal projects. But these disparate, seemingly isolated, small-scale gatherings of extremists may change when viewed together. And images of extremists groups of the 20th and early 21st century gain weight in the light of growing right wing openness and expression around the world , not least in America?

In 2009, when Bruce Gilden went to take pictures of the National Faith and Freedom Conference in Zinc, Arkansas, he had to go to a hotel to get directions to the event. “I was working for Newsweek, it wasn’t difficult to get permission [to attend],” he says. “But they didn’t tell us where the place was. You got to the hotel and they had a sort of treasure island map, showing you how to get to the place. It was very childish, done very crudely. So, we went the next morning and, I don’t know, I took some funny photos. There were maybe 100 people there.”

It was similar for Peter van Agtmael in 2015, when he photographed isolated KKK meetings that were “private and attended by only a dozen or so people”. But in 2017, when he photographed alt-right protests and abundant counter-protests in Boston, Massachusetts, the situation was very different. While the white supremacists at the event numbered only a few dozen, the “counter-protest was attended by thousands of people and was completely public,” he says.

Bendiksen echoes this observation, and muses that the community he photographed back in 2001 would “have a different tonality” now. “Back then this was hidden away: you had to know where it was and so on,” he says. “Nowadays it is entering public discourse in a whole other way. Now that world feels different, so much closer to power and influence. Then, I had the sense that these were disgruntled people, super angry but very far from power. Now I imagine it would feel different.”

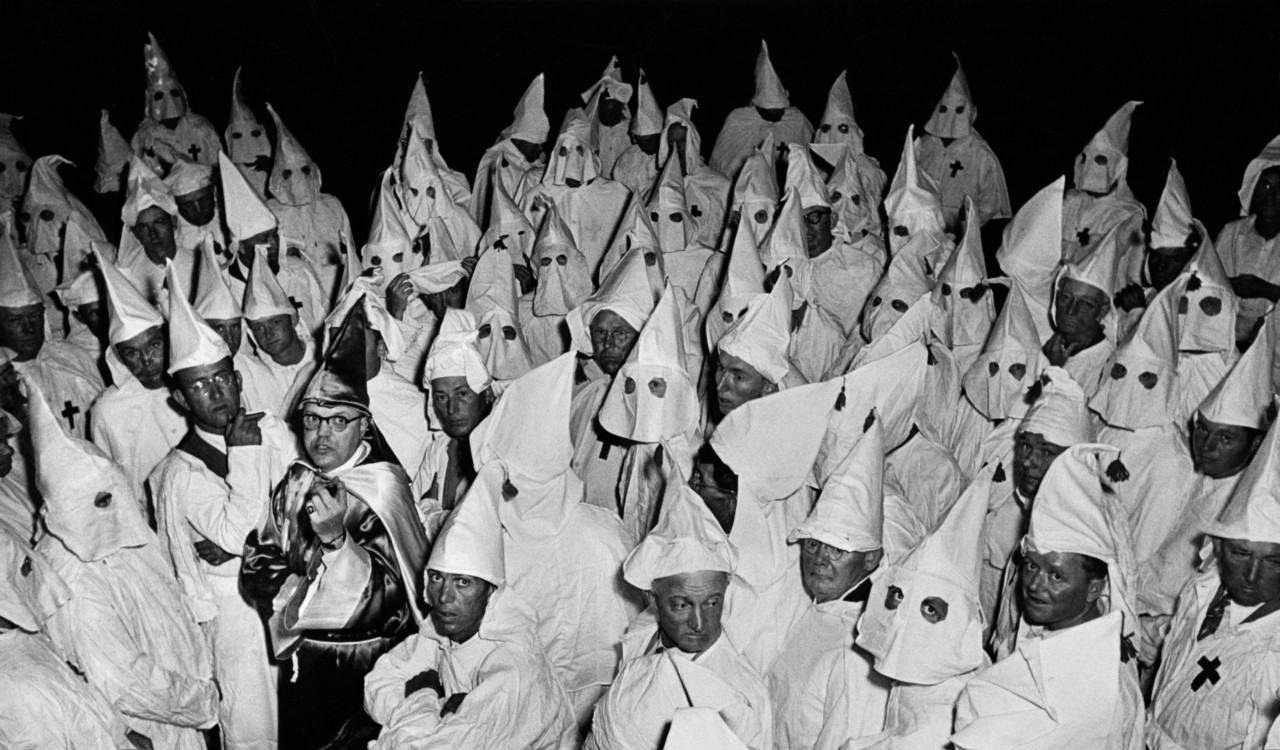

Neo-nazis have been in the US for a long time, as have the KKK that preceded them. The Klan, which has a history specific to the USA, nonetheless embodies and espouses beliefs that put it in line with ultra-nationalists and racist groups all over the world. Anecdotally, de Keyzer says he saw the same people at the neo-Nazi and KKK events which he photographed; in images taken by other Magnum Photos members, the overlaps between such groups are clear: Leonard Freed shot KKK members and neo-Nazis marching together in Pulaski, Tennessee in 1989, for example; the NordicFest Bendiksen shot was organised by a KKK offshoot, and featured an event in which a cross and a swastika were set alight side by side.

"Then, I had the sense that these were disgruntled people, super angry but very far from power. Now I imagine it would feel different."

- Jonas Bendiksen

In fact, even the most cursory look through Magnum’s archive shows that its photographers have been shooting far-right supporters in the US for decades. W. Eugene Smith photographed Klan members in full regalia in North Carolina back in 1951, for example. Constantine Manos’ earliest photographic works were his documentation of his native South Carolina in the 1950s – somewhat unsurprisingly, the Klan made its mark on him and his work also, as he explained in an interview on Magnum, “It was an important subject. I felt that the African American people were held back, and I was on their side. I was very sympathetic to them. We were Greek, and in a way we were outsiders too – outside that typical Southern world. I didn’t connect with the things that were happening in the South at the time.”

Eve Arnold and Thomas Hoepker both photographed American Nazis in the early 1960s, meanwhile, dressed up in full Nazi attire. Their uniforms look fairly shocking to modern eyes but, as Bendiksen notes, at NordicFest forty years later he was struck by “how universal these groups looked”. Outfitted in denim, worker boots and closely-shaved scalps, “these sort of neo-Nazi uniforms are universal, translated from one region to another,” he says. “They felt part of a global movement.”

For the photographers documenting these events, uniforms and insignia make for compelling pictures because they act as clear indications of the beliefs held therein. As Gilden says, his shot of a young child in Arkansas is striking because he’s wearing a shirt, tie, and symbols referencing the Knights Party (the political branch of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan) – and without those visual references, the photograph wouldn’t be so strong.

“It’s a really Aryan picture, a scary picture,” he says. “The kid has a badge on his shirt – that’s what makes the picture so ominous, this sort of Brownshirt look. If he was just wearing an ordinary shirt it wouldn’t be anything.”

But what’s perhaps most thought-provoking about this shot is the way it combines the everyday with extremism – a little kid playing on a swing with affiliations to far right beliefs. It’s something that stands out in Bendiksen and de Keyzer’s images too: Bendiksen showing a family of five who look completely unremarkable other than that the father is wearing a swastika armband, and de Keyzer showing a family picnic in which a toddler sports a KKK outfit. Richard Spencer, celebrity of a recent white nationalist movement in the US, is the individual responsible for coining the term ‘alt-right’. He’s depicted unassumingly in one photo by van Agtmael sitting on a bench in Clarendon, Virginia.

"The far right generally comes in well-tailored suits and snappy sound bites these days."

- Peter van Agtmael

Showing that people who look pretty average can harbour support for the far right, these images pose uncomfortable questions about extremism – positioning it as something close to home and normalized, not Other or confined to those in outlandish garb. It shows how “terrifyingly normal” those who hold such beliefs can seem, as Hannah Arendt put it when describing Nazi war criminal Adolph Eichmann. “I took pictures of regular people in suits,” notes Gilden; van Agtmael echoes his words, observing that “the far right generally comes in well-tailored suits and snappy sound bites these days.”

Perhaps what really hits home in some of these images is the fact that the kids are involved – something that Gilden found visually compelling, but also only too predictable. “What you realise [at these events] is something about parents and children,” he says. “They have this heavy indoctrination, [they] teach them their values, and you see the kids trying to be far right. But that’s what happens with all parents.

“My father was a gangster type, didn’t talk, was physical; I am a physical guy: I have it,” he continues. “I don’t think that ever goes away, even if you realise that’s not the way you want to go. It’s all learnt from your parents.”

Van Agtmael’s more recent photographs from Boston play with a similar shock of the apparently normal, but offer an alternative angle. Shot the week after the deadly rally in Charlottesville, they show very physical clashes between alt-right protestors and counter-protestors – individuals who otherwise look like ordinary men and women on the street.

“While it was nice to see thousands of counter protestors gathered to make a few dozen racist assholes unwelcome, elements of the counter-protest were eager to cause violence and beat up several of the far-right members who had the foolish idea of wandering into the crowd to express their beliefs,” says van Agtmael. “Having been on the receiving end of mob violence before, I was fairly disgusted with their behaviour, even if their general ideology is in line with my own.” Viewing such scenes compels us to consider uncomfortable questions about extremism, the best response to it, and the political temperature in the US (and beyond).