An Atmosphere of Fear: Matt Black on Documenting Migration

The Magnum photographer's years-long projects focusing on migrants have left him compelled, now as much as ever, to address the 'atmosphere of fear' that is damaging the vulnerable

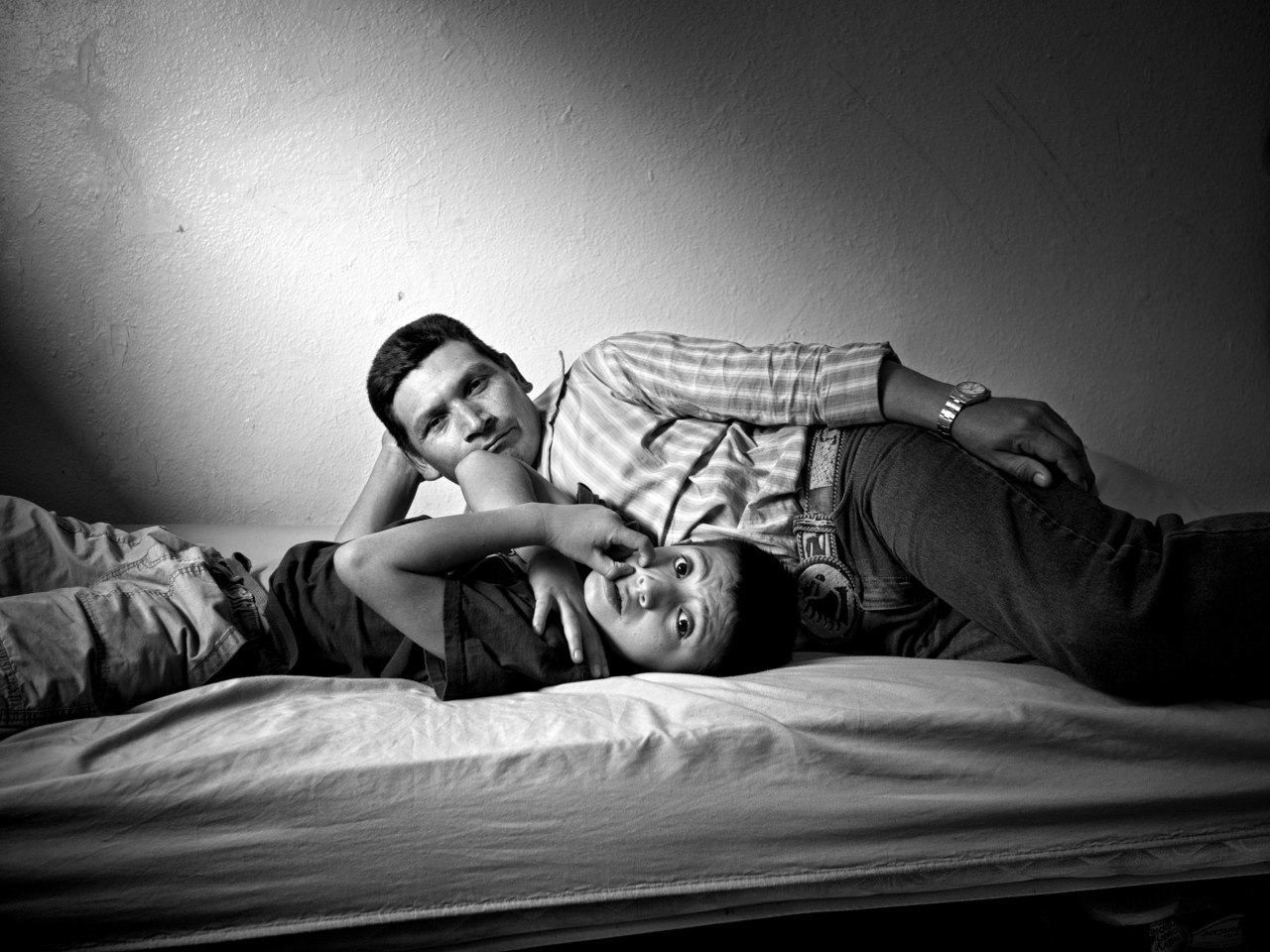

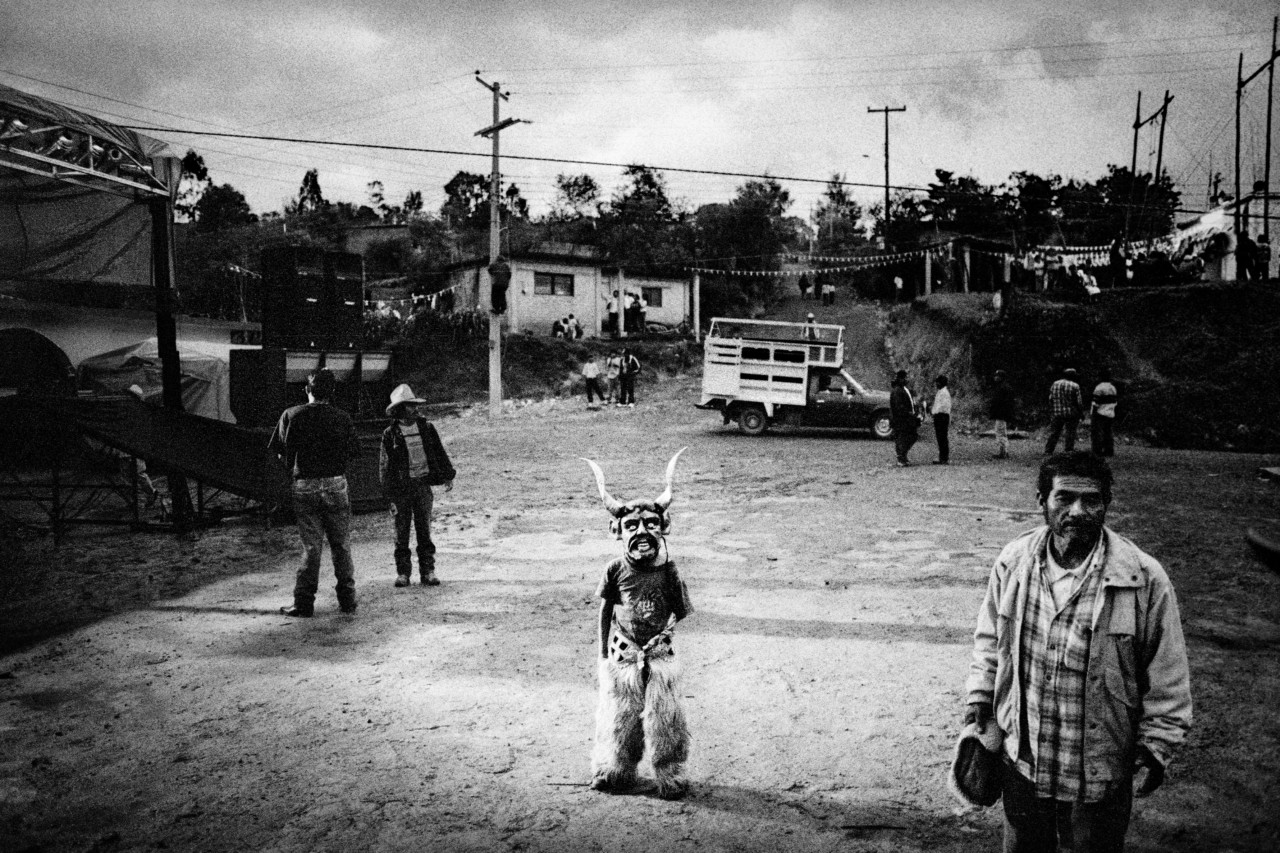

Magnum photographer Matt Black’s work has for years explored the margins where migration and poverty meet, mingle, and feed one another. From his Kingdom of Dust work focusing on the devastating decline in agriculture in his native California, to his ongoing Geography of Poverty project which has seen him travel over 100,000 miles through the United States exploring societies and communities eking a living on the periphery of the American Dream, examining the issues around migration has long been part of his practice.

December 18 has marked the International Migrants Day since 2000, following the United Nations’ Resolution 55/93, passed that year. With migration at the forefront of the global news cycle – whether in relation to the ongoing refugee crisis unfurling in Europe and the Mediterranean, or Central America’s continuing mass migrations – Black’s longterm, engrossed, documentation of migration and the myriad complexities surrounding it offers a very human view of this key issue facing the international community today.

To mark International Migrants Day we spoke to Black about the interplay between migration and poverty in America, the importance of honesty in photography, and the worrying permanence of the fear surrounding those in whose lives are in flux.

You have over your career worked on poverty – most notably in The Geography of Poverty project – and numerous aspects of that have delved into migration, another area of focus for you. Do you think the two issues can be tackled independently, or is it that in the case of America the issues of poverty are almost inextricably linked to the movement of people?

Yes, migration and poverty are definitely connected, maybe more so in the US than elsewhere. The work I’ve done in the US and in Mexico deals with people coming from very traditional, rural places to something more, quote-unquote, modern. There are definitely many aspects to it — economic, political, etcetera — but the part that most interests me is cultural, and how values change. For example, in some of the places I’ve worked in in Mexico, there’s basically no money, but there’s very little of the stigma associated with being poor that you see in the US. You can still be a respected member of the community and not have much. That’s changing, not just in Mexico, but in places like that all over the world. So it’s also about what gets valued and what gets respect and how communities react to these global influences. Now it’s seen as progress to be able to participate in consumer culture — and the way to do that is by leaving.

What do you think has changed, what has left us where we are now, with the majority perception of migration being that it is harmful, damaging, a strain upon one nation and a drain upon another?

I am not sure that’s new. In the US at least, you hear the same negative commentary that people said about immigrant groups 100 or 150 years ago. The same things were said then.

"Without [migrant workers], agriculture in California would cease to exist, and it would take with it about half of the nation’s food supply"

- Matt Black

Being a native of rural California you have presumably been face to face with migratory work for much of your life. How much of a driving factor in your work on migration do you think your personal background played?

Migration has been a big part of life in the area of California that I’m from: large movements of people coming and going. This goes back to the Dust Bowl migration of the 1930s and before, so it’s been a factor for a long time. There’s always been something particularly dramatic about it. That history is built into the DNA of the place, so I have a strong desire to continue this work and to show what’s happening now. Today, people are coming from Mexico and Central America, but much else remains the same.

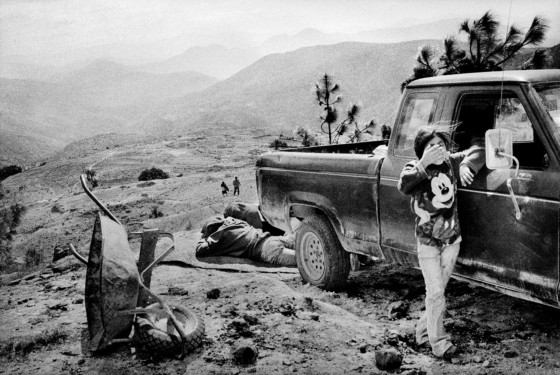

Your California background directly led to your examining Mixtec migrants in Mexico? Their situation at home represents some typical ‘push’ factors for Central American migrants coming to the United States. Do you think that we need to focus more on push factors? The mainstream conversation today seems to often underplay these in favour of a narrative around pull factors.

I think that’s true, and one implies a sympathetic view and the other doesn’t. In the US, no one really talks about the reasons behind migration except in the most superficial way. It’s an arrogance and a lack of curiosity that bothers me, and it’s one of the reasons for doing this work.

"In the United States, no one really talks about the reasons behind migration, except in the most superficial way

"

- Matt Black

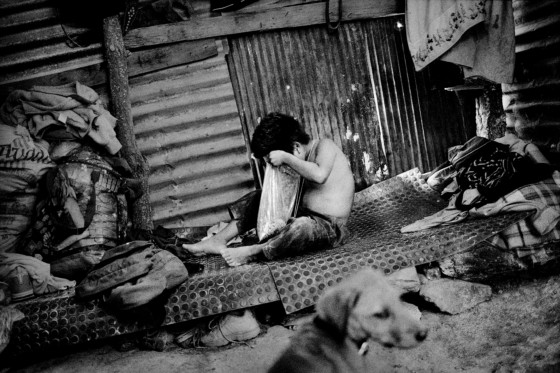

Your work for California Sunday Magazine recently focused on the extreme vulnerability of migrant workers to policy changes, specifically those happening under the Trump administration. How much do you feel that our treatment of migrants reflects wider issues within a nation?

A latent hostility and suspicion of immigrants is not new, but what is happening now is that it’s being channeled and brought to the surface in a really overt way.

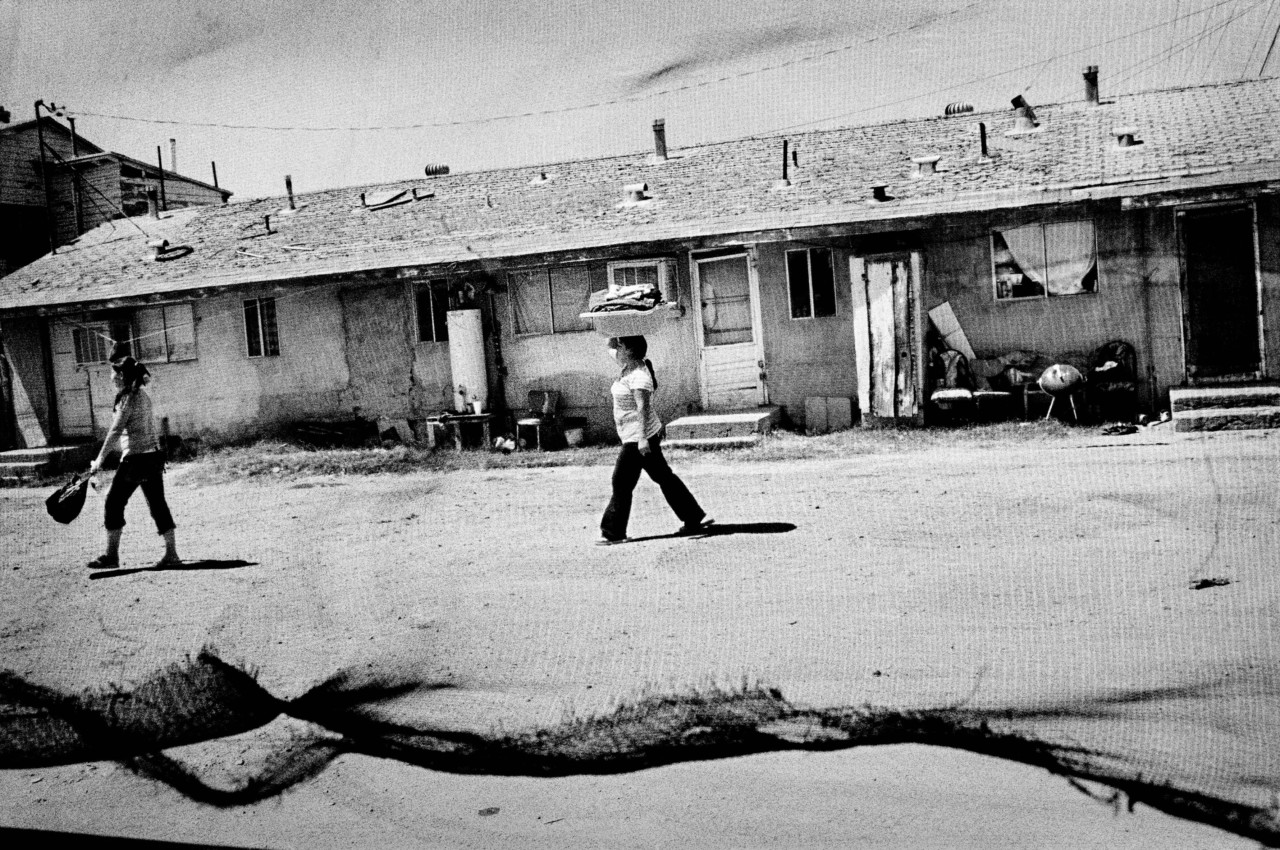

There is it seems a selective approach to migrants: that they are at once seen as a burden and openly discussed as a source of revenue or as a workforce. There is hypocrisy and contradiction there. How does this dichotomy in the perception of migrant workers perhaps reflect a wider myopia in our view of immigrants?

In the US, very little of the discussion acknowledges the country’s dependence on migrant labor. In California, it takes 500,000 people every year to work the farms. Almost everyone doing that work is from Mexico or Central America, and most are undocumented. Without them, agriculture in California would cease to exist, and it would take with it about half of the nation’s food supply. So reminding people of these realities is another function of this work.

"Should people care about what is happening? To me, it’s obligatory"

- Matt Black

You have spoken before about issues around poverty not existing in isolation, that the driving factors are broad, and that the realities and impacts of poverty are everywhere. Do you feel similarly about migration? Do we have a collective responsibility to address the issues? Just being geographically removed from front-page migration issues does not mean a place or community is removed from the impacts?

The entire project behind this work is to get people out of themselves and to see the world from different perspectives. This applies to the subjects I’m working on perhaps more than others, but that question cuts to the heart of doing this work entirely, and the role photography can play in informing people and enriching people’s perspectives about the world. Is the question should people care about what is happening? To me, it’s obligatory. It’s part of being alive.

Another facet of your work on poverty is people’s ability to feel compassion for some forms of poverty, and not others. You have spoken about America’s capacity for sympathy for those in living in poverty in far-flung places, as compared to those in their own towns or neighbourhoods. Do you think that the coverage and management of today’s migration issues suffers similarly? That some migrants are seen as good, or worthy, while others aren’t? How can we address that, and how important is documentary photography in doing this?

I have complicated feelings about the word “compassion” because I think it’s too simple and too limiting of what photography can do. These photos might make some people feel compassionate, that’s fine; they might make others feel upset, that’s okay, too; but the point is one’s work must come from a deeper place than either of those two emotions, and most often it’s coming from a complicated mix of feelings. The imperative is that it’s done according to one’s own compass — that it’s coming from an honest place within you. Then it reflects life. Then it can contain the full range.

"Right now, we have families that are being pulled apart, people who don’t want to leave their homes out of fear of being picked up and deported"

- Matt Black

Do you think we still need to speak about, and cover, the positives of migration: the hope, the aspiration, the changes relocation can offer? Is there a place for more coverage of such aspects of migration in working toward a better understanding of migration? Or do you feel that to focus on this is to effectively sugar-coat the daily horrors and deprivations many are faced with?

I think that all stories honestly told have worth. My work deals with a certain part of the world, and it’s one I have a responsibility to represent. Right now, we have families that are being pulled apart, people who don’t want to leave their homes out of fear of being picked up and deported. This tenor, this atmosphere of fear is damaging people and inflicting harm. And this is going on in California of all places, which is supposed to be one of the most civilized parts of the world. To me, it’s obligatory to address this.