To Obock and Back

Olivia Arthur reflects on her experience photographing the Markazi refugee camp in Djibouti on assignment for the International Committee of the Red Cross

It’s not a big country and the drive from Djibouti City to Obock takes you through most of it, tracing around the Gulf of Tajdoura. The landscape is surreal, literally looking like the Earth has opened up and spilled its insides. I’ve read somewhere that this is the hottest place on Earth, or maybe it was the driest? At any rate, you could be forgiven for thinking that you are arriving at the end of the world. Is there really a town at the end of this unforgiving desperately empty and dry land?

And then – finally – approaching Obock, a sign of life as we see people walking the road, heading out into the nothingness we’ve just come through, carrying bags. Not much further and there is the camp, a huge gated compound with rows and rows of hundreds of tents. The camp has existed for less than a year, set up when Yemenis started fleeing their country in the midst of the war there, but it already has nearly three thousand refugees.

We are just across the water from Yemen, on the other side of the Gulf of Aden. On the other side of the road from the camp is a small brick compound, the much older ‘migrant centre’. It was established to help economic migrants who have tried and failed to cross illegally over to the Gulf to get back home, mostly to Ethiopia. Down in the town there is a small port, a mosque, one cafe, a school and a smattering of tiny grocery shops. Beyond the town seems to be nothing, just desert and scrubland, the road ceases to be a road.

The next morning there is an event at one of the ‘smuggler’s beaches’. IOM (International Organization for Migration) has gathered children from the local community to try and educate them about the value of human life and the dangers of human smuggling. To get to the beach we have to go in convoy because it’s impossible to find one’s way through the empty scrubland.

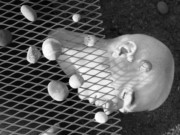

When we get there, we find the remnants of people’s belongings, either the things they have left behind before their journey or things that have drifted back onshore from the sea. There are bags, shoes, jackets, empty bottles and leftover foodstuff. In less than half an hour the kids have filled a container-sized cage with the debris. They are given a snack and little talk about the people whom the things used to belong to.

Young migrants pay smugglers from the local community to take them over to Yemen from where they aim to continue either to Saudi Arabia or the Emirates to look for work. It has been a smuggling route for many years and the migrant centre has been there for those who didn’t make it across, either losing their money to the smugglers or losing heart. Some of the young men I meet in the centre say they paid $750 to smugglers who never showed up; others were so exhausted and famished by the time they made it to Obock, they didn’t want to carry on. But returning home wasn’t such an easy option, most had borrowed money to pay for their journey and couldn’t face going home with nothing. That evening they held a candlelight vigil to commemorate International Migrants Day, a small respite from the boredom of waiting in the compound for the papers and permissions they need to begin the journey on.

"It’s the summer that is hard, the hot winds rip through the tents. It's hell on earth"

-

Over the road in the refugee camp the atmosphere is quite different, here it is not single men but families and there are kids everywhere. It’s quite a new camp but already bustling with activity and small initiatives. Some families have used the extensions of their tents to set up little shops or food outlets. Some men have motorbikes and they taxi people and goods around the camp and up and down to town. It’s blazing hot and the ground is dusty and bright. “Oh no, this is winter?” I’m reassured; “It’s the summer that is hard, the hot winds rip through the tents. It’s hell on earth.”

Nearly everyone in the camp has come from Yemen, most telling me that they fled because it was too dangerous living in the midst of the civil war going on in their country, and that their mixed ethnicity meant they were particularly under threat. Coming from the deeply conservative Gulf country, most of the women I meet are not willing to be photographed, even with their hair or faces covered.

Just living in this way with the rows of tents together is difficult for most of them, not having a private space to go outside. They cook in the porches of the tents and erect various extensions to give themselves a bit of privacy. At one end of the camp I find an extended family that have managed to secure several tents together, put up a large screen and have a sort of private courtyard. In one of the tents all the women are relaxing together and some of the younger ones agree to be photographed; then a divorced woman poses with her children and they all laugh at the audacity.

In another part of the camp I meet a woman who came alone as a refugee. Like most of the families I meet she says she never planned to stay here but wanted to go on to Djibouti city and try to go abroad. But she ended up in the camp, and in a tent on her own she felt quite insecure. Some days later she met a family who let her be a part of their family, she helps to look after their children and sleeps in the outside section between the two tents.

"A lot of protesting ensues, conversations about relatives in Europe or America; no one wants to stay in Obock"

-

Leaving the camp out the back where there is no fence, the scrubland rolls down towards the coast and a hot twenty minute walk takes you to a little cove where men from the camp are catching fish to take home and to sell in the camp. People are resourceful; they find ways to help themselves in between waiting for the arrival of the water trucks or the food supplies. Later I find a man who tries to sell me dried fish skins and shells that he has collected on the beach.

This assignment was part of a year-long collaboration with the ICRC covering their work supporting refugees and migrants around the world.