Opioids in America: An Intimate Portrait of a National Crisis

In the first chapter of a personal project, Jerome Sessini travels to small-town Ohio in a bid to document opioid abuse

The opioid crisis in the United States kills 115 people every day on average. But for photographer Jerome Sessini, the story is not just about the drugs; it is about understanding the context behind the crisis. In this, the first chapter of an ongoing project documenting America’s opioid crisis, we follow Sessini as he travels to Ohio to explore the link between poverty and the rise in substance abuse.

In a small, suburban town in Ohio, prospects are low and opioid addiction is high. Once a bastion of the manufacturing industry, Chillicothe – population 27,000 – is now in decline. Plagued by mass unemployment and the prevalence of opiates, for some, it is a living hell.

This imbalance is being mirrored in towns, cities and suburbs across the United States with chilling consistency, contributing to the deadliest drug crisis in American history. But beyond poverty and poor employment prospects, the origins of the ‘public health emergency’ can be clearly traced to the overprescription of opiate-based drugs during the late 1990s, when healthcare providers – reassured by pharmaceutical companies that patients would not become addicted – began to prescribe them at greater rates.

But as misuse of medication and opioid overdoses increased, it became clear that drugs like OxyContin, Vicodin and Percocet were indeed highly addictive. According to SAMHSA, between 2008 and 2010, around 80 percent of those who used heroin in the past year reported nonmedical use of opioid pain relievers prior to taking heroin, compared to 64 percent in 2002 to 2004.

The engrained social problems that provide fertile ground for addiction, form the focus of Sessini’s series. His journey began in Ohio. Unlike the chaos of Sessini’s next destination, Philadelphia’s Kensington neighbourhood, where drug overdoses play out on street corners – in this midwestern state, addiction tends to take place behind closed doors. “In Ohio the law is very hard with addicts; it’s not a very liberal or open-minded state,” says Sessini. “So [users] tend to hide their addiction.” Authorities were also “totally closed” to Sessini, he thinks because – in Chillicothe especially – they were trying to control the mostly negative press the town had been getting. This meant getting access to those who were willing to share their stories proved difficult.

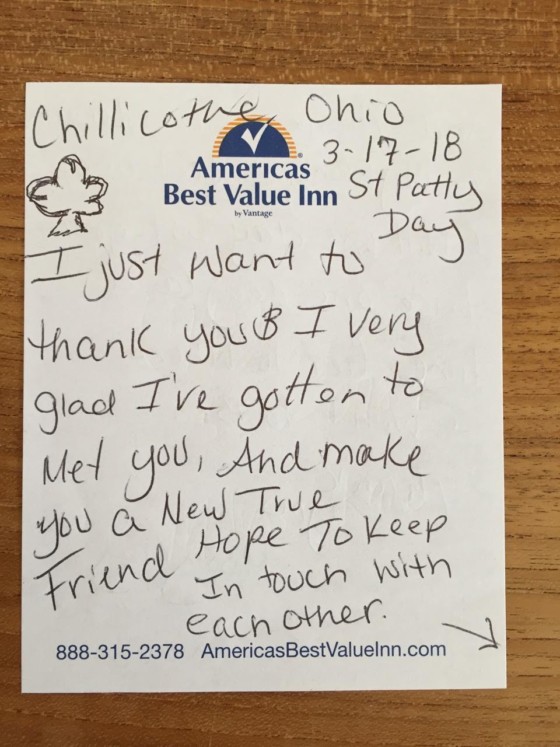

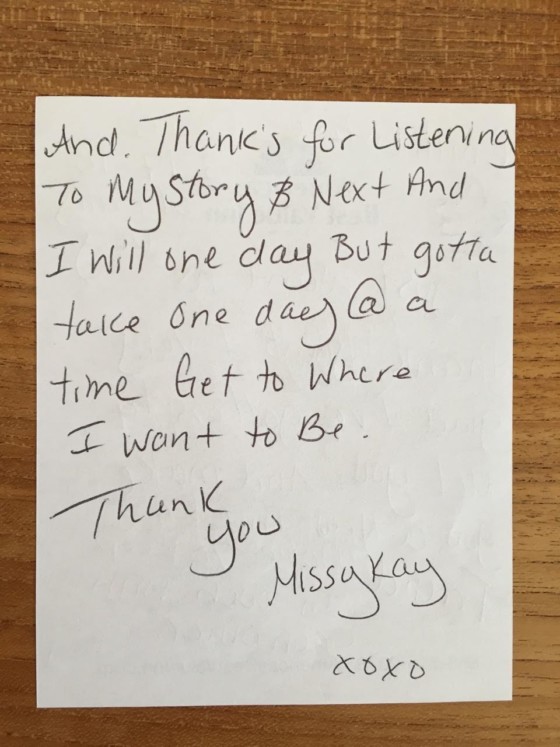

The breakthrough for Sessini came in Ohio’s second city, Cleveland, at the city’s first LGBTQIA sober house. It was there he met Kay, a mother-of-one who became a central character in the Ohio narrative. The 40-year-old had been taking heroin for eight years and at her lowest point was injecting up to 5 grams a day. “I needed a lot of money. I stole from my own parents and ripped off my friends,” Kay told Sessini. “I was violent, a real threat to society.”

When Sessini met Kay, she had been clean for nine months and “felt strong”, despite missing her 19-year-old son. She offered to take Sessini back to her hometown of Chillicothe, which she said was like “hell” with people dying “every day” due to Fentanyl; a cheaper, highly potent synthetic opiate that is increasingly cut into heroin by dealers. Initially, Sessini was hesitant about taking her back to the source of her problems, but she was insistent and he said the pair “shared a mutual trust”.

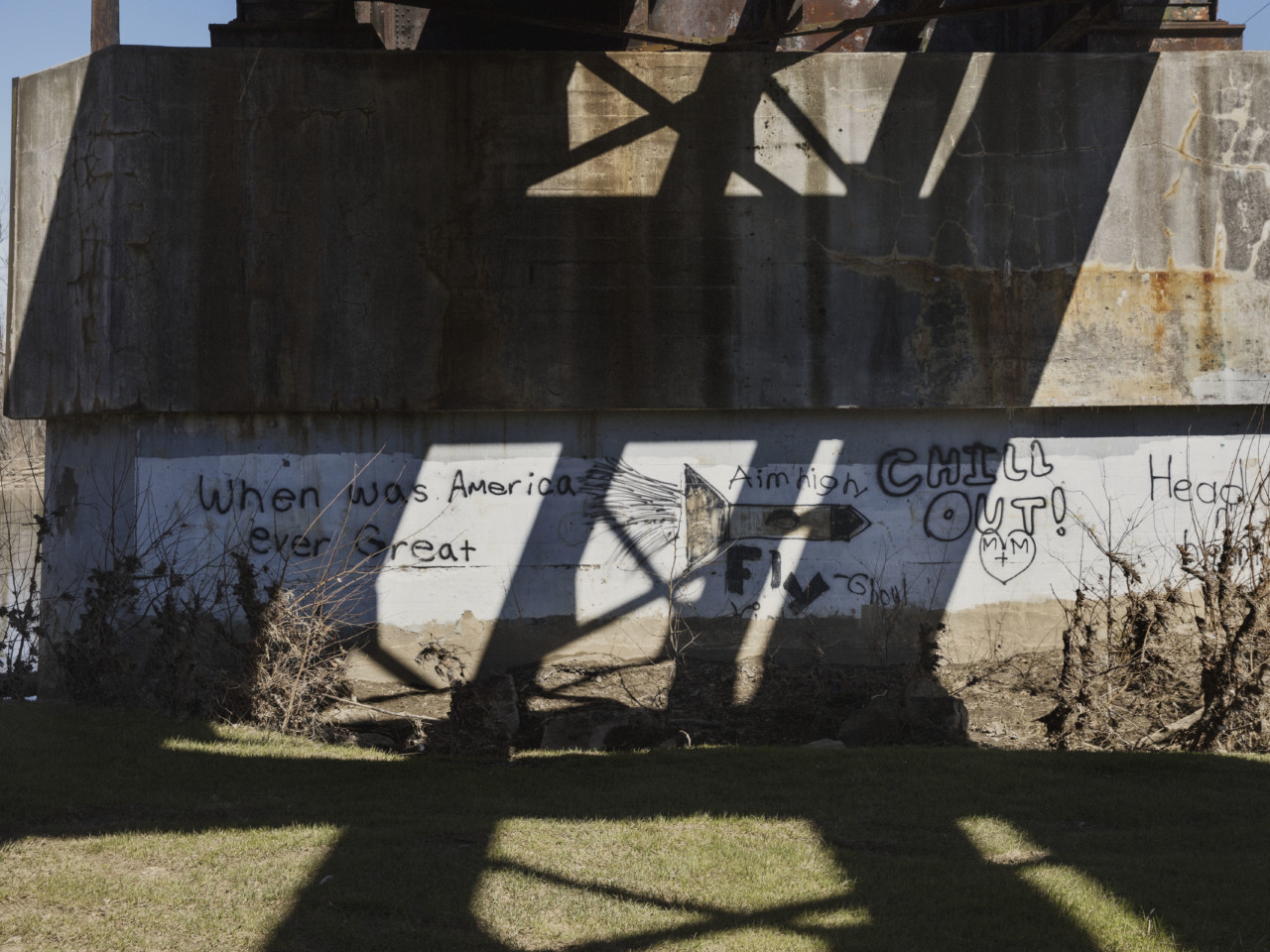

"The landscape was a very important part of this project...by showing the city and the abandoned factories, it shows the place in which this problem grows"

- Jérôme Sessini

A signature of Sessini’s documentary work is the intimacy he cultivates with his subjects. As well as Kay, he spent time with Missy (Kay’s best friend) and Sara (Missy’s cousin). The portraits of the women at home and in their neighborhood collectively offer a record of daily life as a heroin user. Through the illuminating – and at times harrowing – photos, Sessini builds up a personal narrative of addiction.

Intimate portraits may form the heart of Sessini’s work but the environment where addiction festers proved just as revealing. “The landscape was a very important part of this project because it’s difficult to photograph addiction without falling into the cliches and the very trashy pictures,” he says. “But by showing the city and the abandoned factories, it shows the place in which this problem grows. Of course, the main rise in addiction is because of overprescription, that’s a fact. But it’s also the environment.”

Though the opiate crisis is infecting cities and countryside alike, it was the small town story that Sessini had a particular affinity with. “I grew up in a small town in the east of France so I know exactly how it happens,” he says. “When you live in a small town, you’re bored, there is nothing much to do around you; it’s easy to fall into drugs and addiction. You fall into a kind of negativity; a nihilism. ” What he found in Chillicothe was no different.

For young people living in towns haunted by a dying industry that is unlikely to be revived, it‘s difficult to see a future. Route 23 – also known as the 23 pipeline – is one landmark that Sessini picks out. The highway cuts Chillicothe in two and offers easy access to dealers from Columbus and Detroit. Meanwhile, the mossed-over basketball courts of Youngstown and the weed-filled gas stations of Portsmouth, which Sessini also visited, are further signifiers of Ohio towns left to decay.

Depressed economies may contribute to high substance abuse rates, but it was important to Sessini that he showed that the journey to heroin addiction should not be typified. As he says, opioids don’t discriminate: “Black, white, rich and poor… for all it’s the same hell.” Missy’s cousin Sara, 27, became addicted to opioids after an oxycodone prescription for pain relief from scoliosis ran out and she turned to heroin instead.

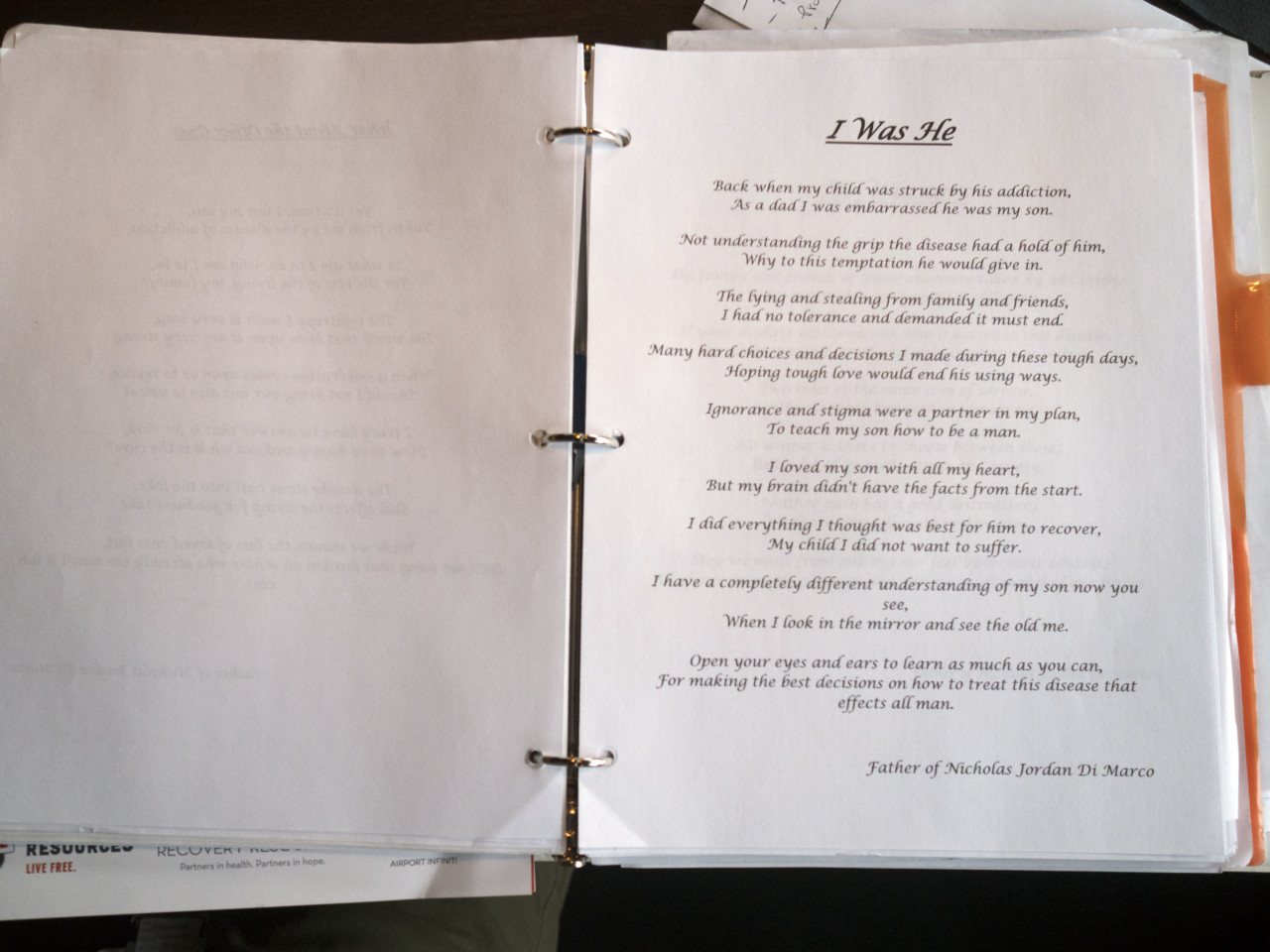

The idea that addiction happens to ‘other people’ is no longer tenable, as Sessini found out when meeting the families of victims in Cleveland and Youngstown, Ohio. In Cleveland, Sessini met Fred Di Marco, whose son Nick, a good student who loved sports, died aged 18 after taking heroin laced with fentanyl in 2015. “It’s not like the crack epidemic of the nineties,” Sessini notes, highlighting that opiate addiction is prevalent across social divides. Nick di Marco’s father, Fred, and Don le Giudice, whose son had also died young of an overdose, are both from conservative, middle class backgrounds, far from the stereotypes of neglect and poverty that often accompany society’s image of drug use, says Sessini. “To them, drugs were bad; something that could only happen to the cliché junkie. And then, when they lost their kids, they totally changed their point of view. They realized these people are not criminals; they’re sick, they need help and support.”

Fred di Marco now finds catharsis through his work with drug prevention groups, by offering support to parents in similar situations and through poetry, which he writes every day. One poem reads: “I loved my son with all my heart/ But my brain didn’t have the facts from the start/ I did everything I thought was best for him to recover/ My child I did not want to suffer.”

Sessini’s work in Ohio began, and ended, with Kay. After six days spent in Chillicothe visiting old friends and old haunts, Sessini drove her back to the sober house in Cleveland. But the pull of her old life proved too much. She asked Sessini to drive her back to Chillicothe to be with her son. “I said: ‘No way. If you go back, you go back to heroin’,” says Sessini. “I dropped her off at the sober house and I left.”

A week later, Sessini got a call from Kay, who had made her own way back to Chillicothe and was begging for money for ‘a bus ticket to return to the sober house’. “I refused,” says Sessini. “But I had a real reckoning of conscience. I felt very guilty.” The manager of the sober house believes Kay manipulated Sessini from the start but Sessini doesn’t think so. “I had a lot of proximity to drugs and violence when working on my project ‘Wrong Side’,” he says. “But I never felt this guilt.”

In the next chapter of the series, Sessini travels to Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood. It has become a destination for heroin users all over the country because of the wide availability of some of the cheapest and purest heroin in America.