Philadelphia’s ‘Badlands’: At the Heart of the Opioid Epidemic

Photographer Jérôme Sessini travels to Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, a destination for opioid users because of the ready availability of cheap, strong heroin

WARNING: The following post contains graphic images

The opioid crisis in the United States kills 115 people every day on average. But for photographer Jérôme Sessini, the story is not just about the drugs; it is about understanding the context behind the crisis. In this, the second chapter of a series documenting America’s opioid crisis, we follow Sessini as he travels to the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, part of which is known locally as the ‘Badlands’.

The Northeast Philadelphia neighborhood of Kensington is like “a limbo of lost souls,” says Sessini. “You have people everywhere hanging around or lying on the floor, almost dead,” he adds. “It’s not just one or two people; they’re everywhere – and it’s a big neighborhood, it’s not just one street.”

The reality facing one of America’s poorest districts is far worse than any imagined purgatory. The Pennsylvania city—which forms the backdrop of Sessini’s second chapter on the country’s escalating crisis—has the highest poverty rate among the nation’s ten largest cities. It also had the second highest rate of drug overdose deaths in the country in 2016.

Sessini attributes the high overdose rate to the ready availability of some of the “cheapest and most pure heroin in America”. An increasing amount of the heroin on sale here is cut with fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that can be 50 to 80 times more powerful than heroin. Fentanyl or fentanyl analogs were present in 84% of opioid-related deaths in Philadelphia in 2017, up by 27% on the previous year. “This is why I decided to go to Kensington,” Sessini says. “Here, one bag of heroin costs only $5. You don’t even have to look for it; on every corner of the neighbourhood people are selling [heroin] and often giving it away for free, to attract new clients or maintain customer loyalty.”

This prevalence makes for big business and the city’s once thriving textile and cigar industries, which peaked in the 1950s, have now been replaced with another lucrative economy. In a place where job opportunities are extremely scarce, the narcotics trade is a tragically appealing option for young people. “Everything in Kensington is related to drugs in some way,” says Sessini. “I was told that even the small shops that sell food are used as a front for drug money.”

As a consequence, Kensington—part of which is known locally as the ‘Badlands’— sees a constant influx of new people looking for a cheap fix. On Sessini’s second visit to the neighborhood just one and a half months after his first, he barely recognised anybody on the streets. “I think there is a high turnover in Kensington,” he says. “People move, people die or go to jail or to I don’t know where and all the while there are new people coming. It was very hard to follow anyone because you see them one day and the next day you don’t know where they are.”

The ever-changing cast of characters made it more difficult for Sessini to navigate than Ohio – the setting for his first chapter—where he was able to closely follow the same people.

But his access was aided by a Kensington-native called Nathaniel, a former heroin user now Percocet addict who proposed himself as a guide. “He’s very intelligent, very brilliant and knows everything about the neighbourhood,” says Sessini. “But he was difficult to work with because he was always high on drugs. He’s tried to stay away from heroin but has replaced it with Percocet, which is more expensive and has the same effect.”

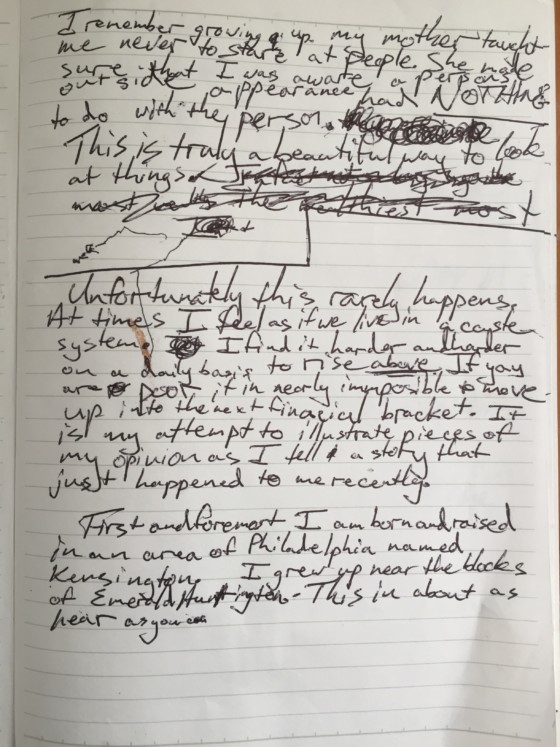

Sessini encouraged Nathaniel to share his story in his own words and in one revealing account he writes: “I remember growing up and my mother taught me never to stare at people. She made sure that I was aware a person’s outside appearance has nothing to do with the person. This is truly a beautiful way to look at things. Unfortunately this rarely happens. At times, I feel like I live in a caste system. I find it harder and harder on a daily basis to rise above. If you are poor, it is almost impossible to move up into the next financial bracket.”

As well as reflecting on his own internal struggle, Nathaniel also showed Sessini the struggle on the street. He led him to the heroin highway of Kensington Avenue, where a thriving drug business works with shameless efficiency. He took him to ‘drug encampments’ that sprawl under bridges and along avenues, where addicts, cocooned in dirty blankets and makeshift beds, spend their hours—mostly undisturbed by police—injecting and sleeping. They went to Jasper Street, where Sessini found a mother and daughter prostituting themselves on opposite sidewalks to fund their respective addictions.

The desperate and seemingly cyclical stories of the people Sessini met nearly all began with the misuse of prescription drugs. One 35-year-old woman living under a bridge near Kensington Ave, started using morphine and Oxycodone aged 13 following a car accident, before later moving on to heroin. Jay, 41, a former Marine who served in Afghanistan, first started taking pain killers after a car accident and later transitioned to heroin. Meanwhile Shannon, 34, from Delaware County, started taking Percocet aged 15 and then got hooked on heroin because it was considerably cheaper.

Though drug use is often all consuming, Sessini sought to show another side to the addicts’ stories. “Addiction is a disease, but society sees addicts as criminals,” says Sessini. “Rather than show that, I tried to suggest how opioids users are trapped not only in their addiction but also in the negative environment. So I also focused on portraits, the streets, the cityscape…to photograph someone with a needle in their arm doesn’t tell you much.” He quotes from the short story Morphine, the fictional diary of a morphine addicted doctor, by Mikhail Bulgakov: “I’m afraid of the slightest noise, I hate everyone when I’m in the abstinence phase. People scare me. In a phase of euphoria, I love them all, but I prefer loneliness.”

The high concentration of drug activity has made Kensington acutely segregated, with entire avenues and blocks becoming no-go zones for non-users. With the help of a large investment plan, authorities are hoping to attract a wealthy population to Kensington and the traces of gentrification can already be seen in the surrounding streets. “Little by little addicts are pushed back further and further, if they do not die before,” says Sessini. But a full transformation is still a long way off and the owner of the house where Sessini was staying—just three blocks from Kensington Ave—said she “never, ever” ventured there. “It’s like an invisible border that people just don’t cross,” says Sessini. “They’ve heard about it but they just don’t want to see it.”

But for some, reality is unavoidable. Sessini joined first responders on two ‘ride-alongs’ as they combed the streets looking for casualties. “The second time we found a man on a pavement who was still conscious but close to overdose,” he says. “They gave him the Narcan just in time and then they took him to the ambulance.” Narcan—the commercial name for naloxone—is designed to reverse a heroin overdose by blocking the brain’s opioid receptors and restoring normal breathing. All emergency staff in Philadelphia are required to carry Narcan but it is mostly the firefighters who administer it. Such is the rate of overdose here, regular citizens are also encouraged to carry it in case of emergency.

Kensington’s community centers also shoulder the weight of a heavily addicted, poverty-stricken populus. The San Franciscan Inn opens every day from 4.30 to 6pm to offer food and clothes to the needy. Though it is mostly populated with heroin addicts, the Inn “does not pretend to enforce drug prevention”, says Sessini. There are other organisations in Kensington for that; the Last Stop center, where addicts can go for support and advice, and Prevention Point, where addicts can apply to take part in a heroin-substitute programme.

But rehabilitation can often be meaningless when dangerous triggers are still close by. A heroin user called Joshua, 28, who arrived in Kensington six months ago, has been to rehab several times but told Sessini that he didn’t get the help he really needed. “He needs not only to get clean and get help finding a job,” says Sessini. “But he needs to leave Kensington.”