Challenging the Established Picture

Mark Sealy walks us through his ongoing project reimagining African political history through an intervention on the Magnum Photos archive, and exploring the work that images do in culture, in relation to race, as well as colonial and postcolonial African histories

The following article explores Mark Sealy’s recent curation of the Magnum Photos archive on Africa. The project aims to serve as inspiration for contemporary photographers to respond to with new work.

Four grants will be allocated to early-career South African photographers. Two of these grants will be available on application via an open submission process, and two of these grants have been awarded through Magnum’s ongoing relationship with the Of Soul and Joy project; a workshop and talent development program in Johannesburg, South Africa.

For full details on the grants available, and to apply, go here.

Archives capture history insomuch as they enshrine the perspectives of those who have been privileged enough to narrate and control how it is recorded. At the core of Mark Sealy’s work is a motivation to challenge the notion of archives as singular repositories of historical truth-telling, which he argues has influenced not just the history of photography, but our collective understanding of history itself. By being open to diverse perspectives, Sealy aims to broaden our understanding of history, and expose the power structures that have, and continue to, allow established narratives to dominate.

“I think once we get ourselves over the idea that photography is not this fantastic invention, the undisputed eye of the world, but is just another dominant tool used to narrate Eurocentric perspectives, then I think we’re in a place where we can begin to unpick photography’s social meanings through the prism of different ways of seeing… It’s a form of curatorial resistance work. It’s about understanding that things aren’t always the way that powerful cultural institutions tell us that they are.” The solution lies in locating “our silent history”, as he described it when speaking at a Magnum talk on archives at the Barbican.

"It’s a form of curatorial resistance work"

- Mark Sealy

In a new project, which sees him working within the Magnum archive, Sealy is unpacking various narratives of African culture in an attempt to reveal alternative, perhaps lesser-known, or lesser-seen moments of that continent’s history. The idea being that these stories will serve as a catalyst in a call-out to a new generation of photographers to respond with their own original work. Some of the stories he has extracted from the Magnum archive have been left out of western epistemes, slipping from collective, national, and international memory. Others were actively suppressed by colonial forces operating in a wider cultural context, while some new photo edits shine light and offer alternative perspectives on what might have previously been misunderstood, denied or buried.

The stories he has chosen to focus on are varied – spanning the French-Algerian War from 1954 -1962, the 1948 South African Election, the Mau Mau uprisings through the 1950s, the 1969 Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algiers, and The Rumble in the Jungle between Muhammad Ali and George Forman in 1974. Here Sealy explains a number of themes from his new curation of the archive.

What is not in the curation

What is important to note, explains Sealy, is what is absent from the curation. “One of the things that’s not in here is images of broken black bodies. When you look through photographic archives that concern the continent of Africa, or indeed Eurocentric archives that have a focus on the southern hemisphere, they are full of devastation – detailed images of broken black, brown, yellow bodies. I argued in an exhibition that I did in 2012 – titled Human Rights Human Wrongs – that this image of the broken black body is really prevalent in many Northern photographic archives; that the focus on the black subject in the past has been disproportionately caught up within the disasters of conflict. And that’s still very much the frame in which we reference the South today. And we don’t see the European body treated, photographically, in the same way – especially post World War II.

"Some stories in the curation shine a light on events about which little is known in the West"

-

Amplifying seldom-told stories

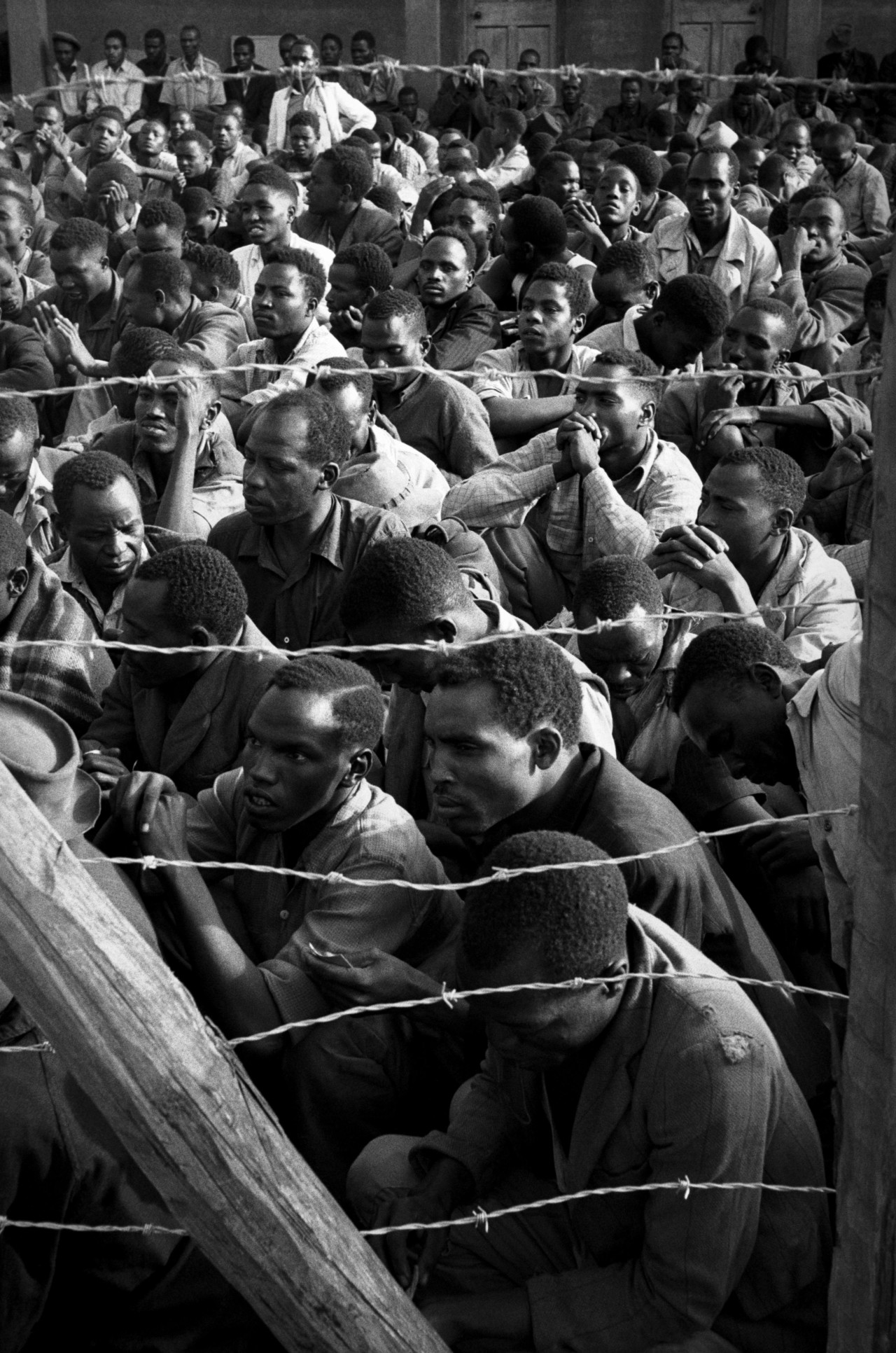

Some stories in the curation shine a light on events about which little is known in the West. Stories like the 1975 Green March in Morocco: a demonstration of some 350,000 Moroccans demanding that Spain hand over the disputed province of Spanish Sahara, or the treatment of Mau Mau resistance fighters in Kenya by the British authorities in the 1950s.

“It’s only recently that there was recognition by the British of the traumas that they put the Mau Mau resistance fighters through,” says Sealy. “When we think about World War II, concentration camps… These images invite us into a conversation on the nature of fascism and the application of international human rights agreements. Through images like these from the Mau Mau resistance movement we can ask what lessons – if any – have been learned from the experiences of the Nazi concentration camps and racial hatred… In terms of the history of Human Rights it’s quite clear that there’s a kind of duplicity involved concerning colonized people’s rights, especially those who continued post WWII to fight for the freedom and equality that was promised.”

"Through images like these from the Mau Mau resistance movement we can ask what lessons - if any - have been learned from the experiences of the Nazi concentration camps and racial hatred"

- Mark Sealey

A New Perspective on World Events

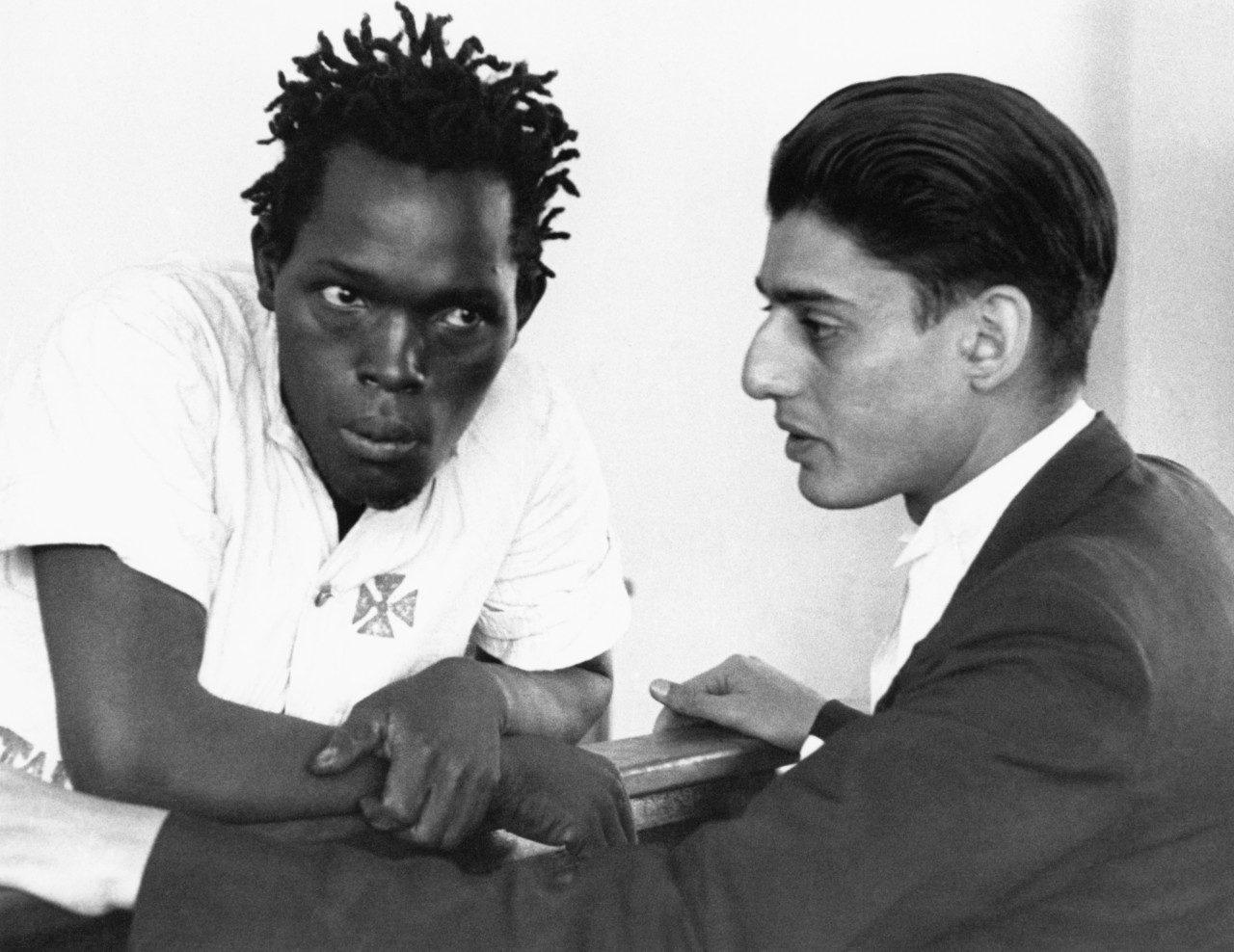

The curation draws attention also to unseen perspectives on well-known events. One such is the Algerian War of Independence, which ran from 1954 to 62, and saw Algeria eventually gain independence from its colonial ruler, France. Sealy’s curation includes a photo essay by Kryn Taconis, a photographer working for Magnum at the time, who had photographed a unit of Algerian freedom fighters.

When word got out that a photographer was documenting the everyday activities of such fighters – in theory giving them a more human face – the Magnum office in Paris became very concerned. There were fears that these images might be seen by the authorities as positive propaganda in favor of the Algerian Independence movement, and also that their publication might result in acts of violence against Magnum photographers, and indeed Magnum’s Paris office. Cartier-Bresson is reported as saying, in Russell Miller’s book, Magnum: Fifty Years at the Front Line of History, “It was not possible [to publish these images] because in those days one would have had a plastique [bomb] through the door…”.

As a result the essay was never syndicated. This collection of images, like many others, has been missing from the wider narrative for decades. By bringing it back into focus, Sealy hopes to add new knowledge to how this conflict is seen.

“[This work] reminds me of all those absences from narratives that surround the World Wars, and all those voices that get suppressed and silenced. Obviously of late there has been some adjustment work produced to argue for wider, more inclusive world history, but in general, if we go look back through time, the idea that African soldiers for example were fighting for the liberation of Europe and the rest of the world is not in the DNA of people’s consciousness. Being able to pull images like those of African soldiers out of the Magnum archives, simply reminds us that these men where there, and the evidence of their endeavor becomes visible.”

"Being able to pull images like those of African soldiers out of the Magnum archives, simply reminds us that these men where there, and the evidence of their endeavor becomes visible."

- Mark Sealy

The Power of Banal Images

What is interesting about Taconis’ Algerian work, argues Sealy, is that the images are what he describes as “a quiet story”. There is no combat, or captured French soldiers being tortured, but simply images of Algerian fighters going about the more banal aspects of their day, being comrades in arms. “In my view, there’s nothing really radical there when I look at the whole edit. There is nothing really offensive that could charge the photographs with being overtly propagandist in any form. It’s like, here is a small regiment of soldiers, sitting there going about their business, and that’s just what they look like: a bunch of men, human subjects, doing their everyday tasks.” The idea that they should not be seen opens the door to discussion on the inherent nature of colonial thought: The power – and perceived threat – of these images is in their ability to humanize their subjects.

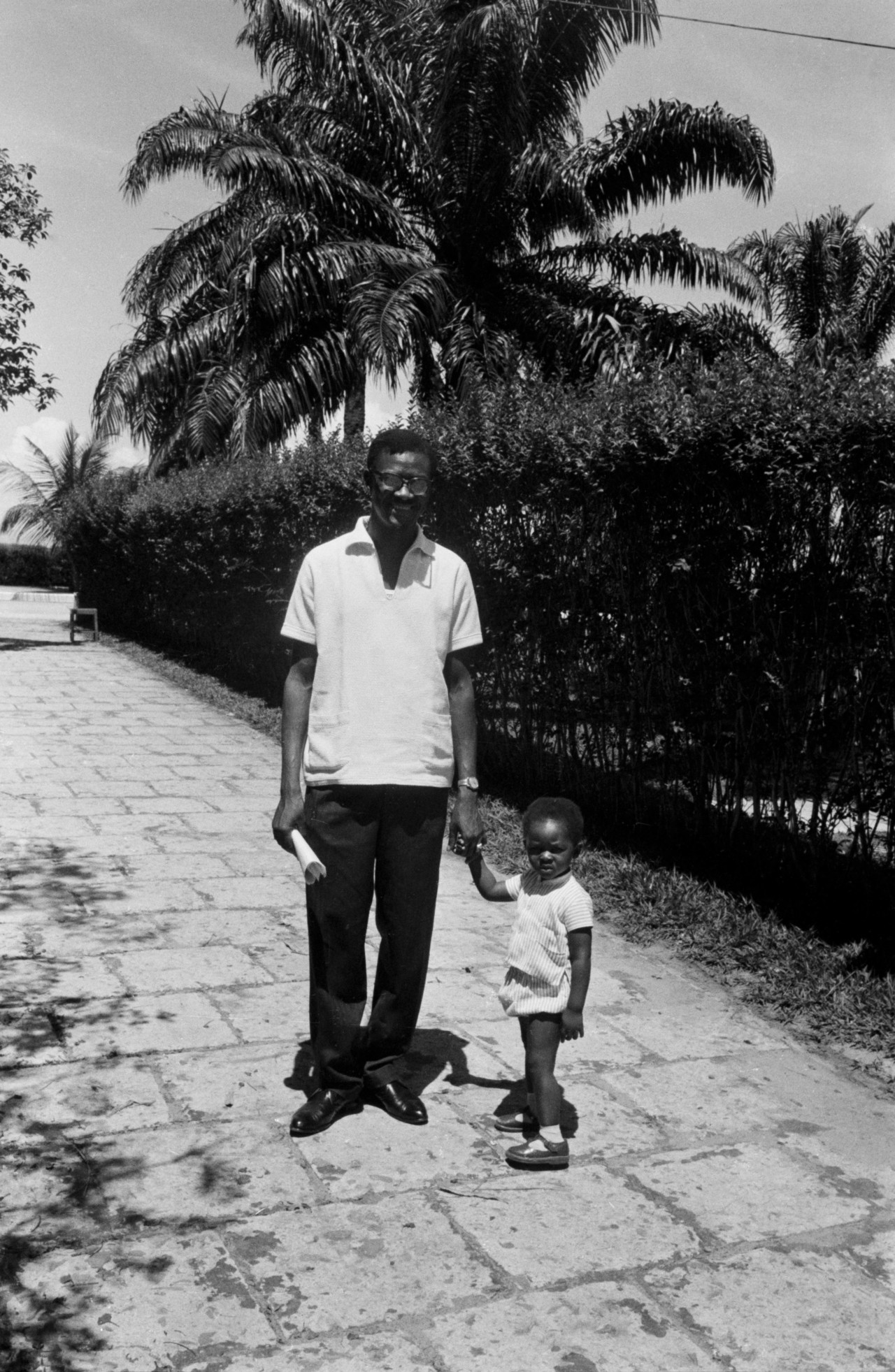

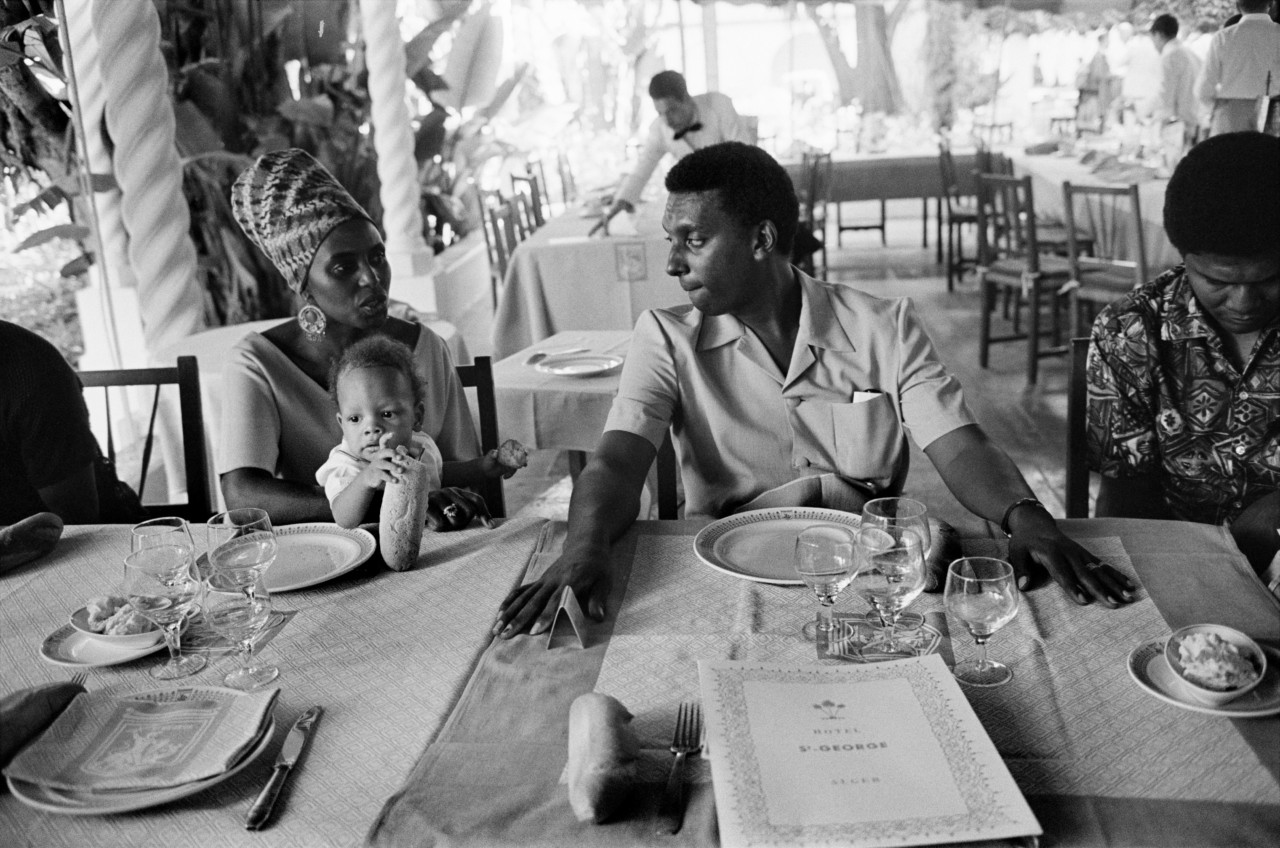

The same can be said, explains Sealy, of photographs he found in the archive of Congolese politician Patrice Lumumba: “Lumumba was described in the West as a kind of wide-eyed devil, and I think the image of him standing there in the street with his child, just as this kind man with a family, is a fantastic moment in helping us understand him. It relocates him beyond the space of politics and into the realm of the family and home”

"It’s really important that we measure and care for those simple moments, which, if they're not reflected back on, if they're not there, we lose sight of them."

- Mark Sealy

“No one would really have been that interested in a photo of Lumumba in the street with this child. It’s not that interesting as a photograph, but it is interesting now that we know he was killed and assassinated and was fleeing with his family, so it’s again what was seemingly irrelevant at the time can have a huge charge if we allow images to escape from the archive and into the contemporary public realm. It’s really important that we measure and care for those simple moments, which, if they’re not reflected back on, if they’re not there, we lose sight of them.”

These moments, though pivotal to the reworking of the archive, are hard to come by. There are very few like this, and Sealy is quick to point out that this is not to say these moments were seldom, but they point to a bigger societal picture, indicating what photographers, and by extension the publications commissioning them were trying to produce and project onto the world.

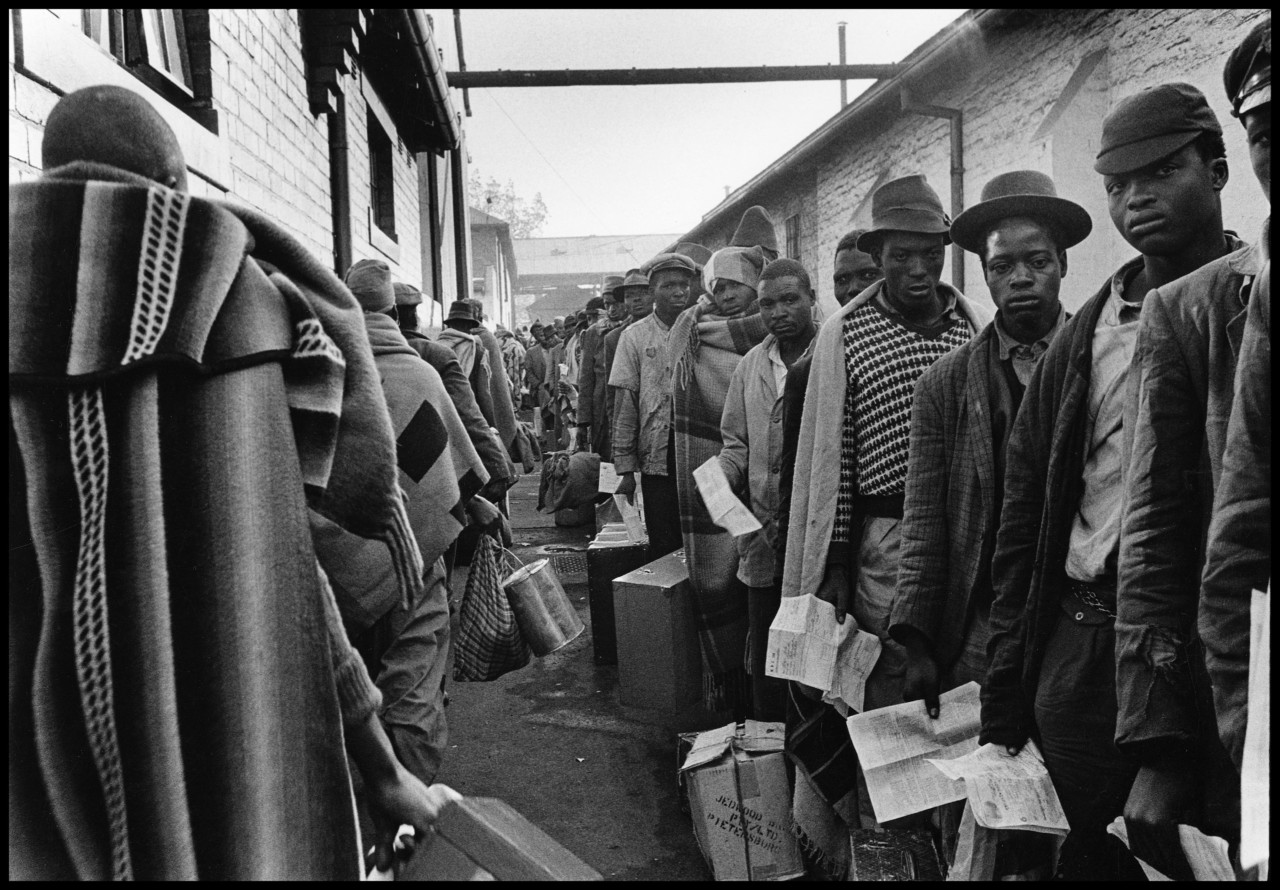

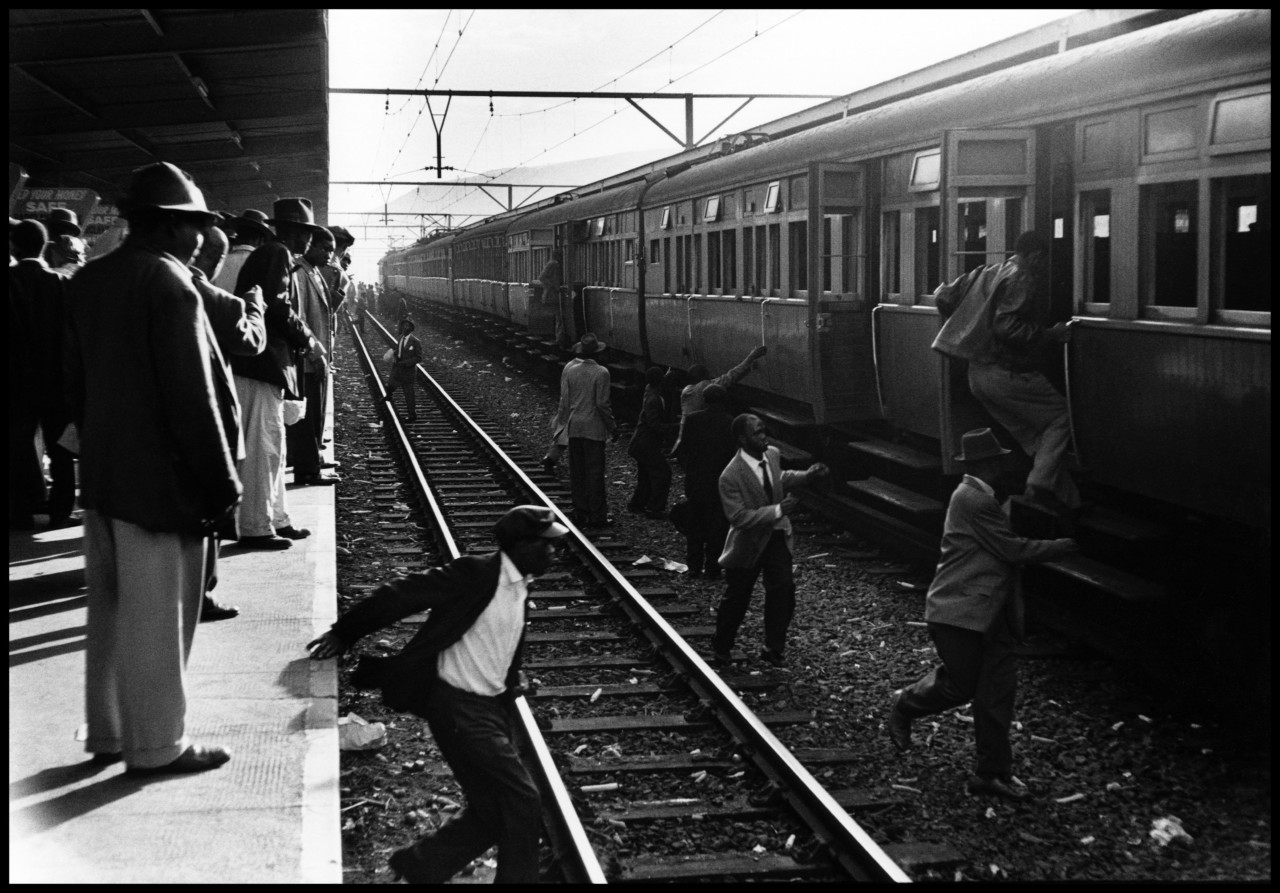

A Document of Struggle

A curatorial project based on the idea of ‘Africa’ seen through the Magnum archives would not be complete without acknowledging South Africa’s apartheid years. Black South African photographer Ernest Cole’s astounding body of work “House of Bondage” provides a first-hand testament to the daily brutality experienced by Black South Africans under the regime.

1948 saw the Universal Declaration of Human rights adopted by the UN, however it was also that very year that the Apartheid regime was brought into power. “I think by bringing that work to the fore, it enables us to have a conversation around a post WWII story – the world had been devastated by, you could argue, racism, and the impact of Fascist ideology. Towards the end of 1945 you had the idea that the world should move into a more engaged, humanitarian period – no more disastrous wars, and the passing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights – Universal being the key word should have embraced all mankind. But somehow, in the case of South Africa, the UN allows this regime to emerge… So, the idea that the world stands behind these violent moments, lets these events occur, is quite important now to rethink how these political acts concerning race affect our present.”

"The idea that the world stands behind these violent moments, lets these events occur, is quite important now to rethink how these political changes affect our present."

- Mark Sealy

“Photographs for me offer the opportunity to examine our different temporalities in time and space. And we all live in different moments. A Black South African subject in time of apartheid is living in a totally different time and space from a White South African subject. They are in parallel but different temporalities.”

That Cole’s work recently came back under Magnum’s representation is also significant for Sealy: “For me it’s all about care for work, who advocates work, who manages work that’s very old fashioned viewpoint but I still support the underlying principle of curatorial work being locked into ideas of caring and its great that Cole’s work has been cared for in the past and will be cared for in the future.”

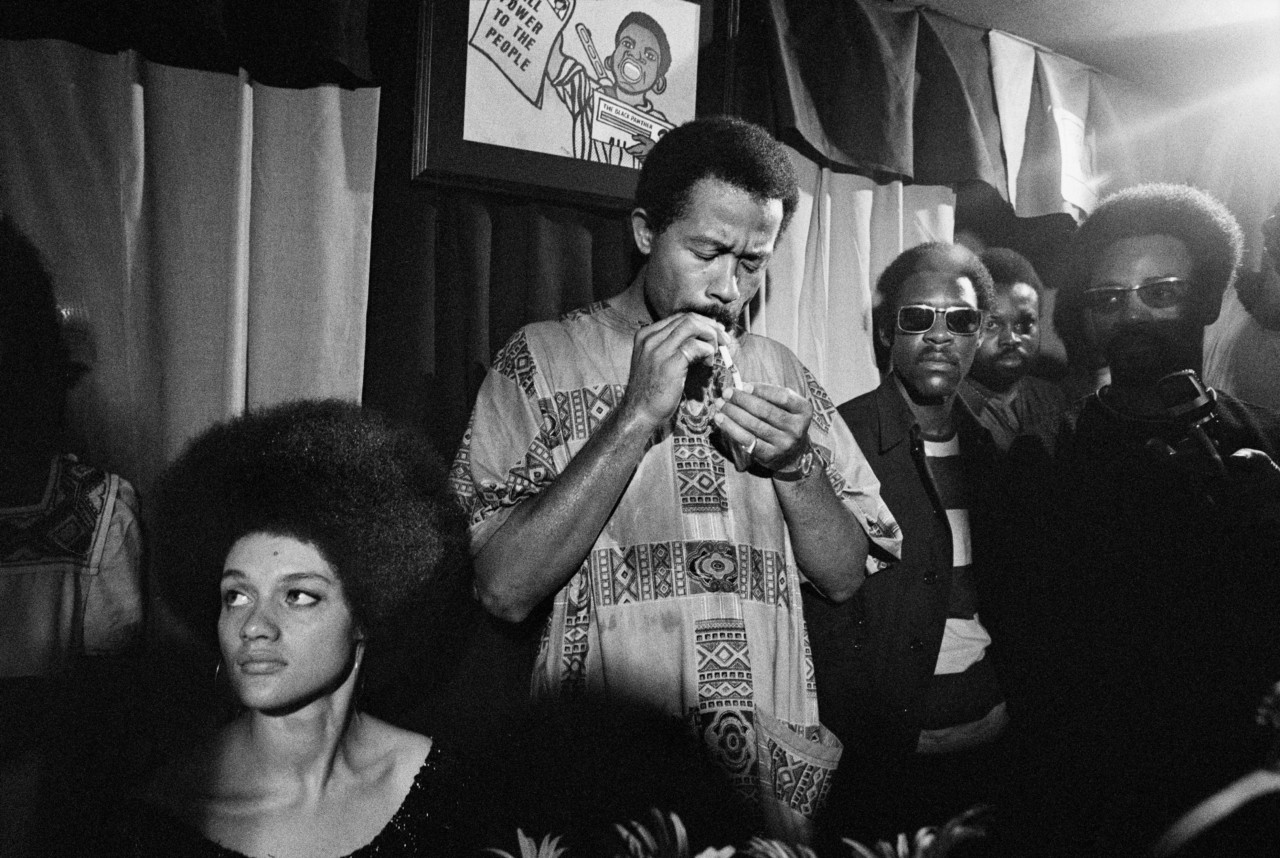

The First Pan-African Cultural Festival

Sealy’s curation focuses also upon moments of affirmation, including a comprehensive selection of images made during the first Pan-African Cultural Festival, a moment where Black Africans and those of the African diaspora came together in Algiers, in 1969, and asserted their cultural worth. Sealy likens this to contemporary international arts and culture events like the Venice Biennale. “Why did they need to do this?” asks Sealy, “Because historically they have been repressed, historically have been held back, historically they have been told that they are a-cultural, they have been told that they don’t have a history, and these moments are big celebrations, and they essentially provide people with a sense of human worth.”

“I like the idea of thinking about this material through inviting us to think about different cosmologies, different ways of looking up to African cultures, as bright stars in the cultural galaxy. Thinking about Africa for those in the diaspora as a place to look up to helps us begin to re-dream, re-imagine, repossess a sense of being. This is done through an identification with the deeply cultured spaces and histories that make up Africa and if you can’t imagine what freedom looks like, then it will never be.”

Sealy is keen to show how the African countries were in dialogue, working together as a collection of Pan-African states, “a place where the economies and their cultures could be discussed and where alliance could be made.”

"I like the idea of thinking about this material through inviting us to think about different cosmologies, different ways of looking up to African cultures"

- Mark Sealey

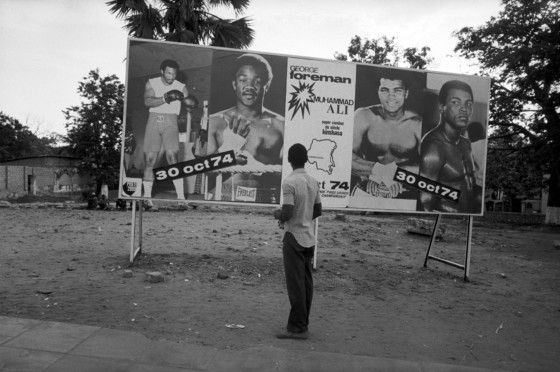

African Soft Power

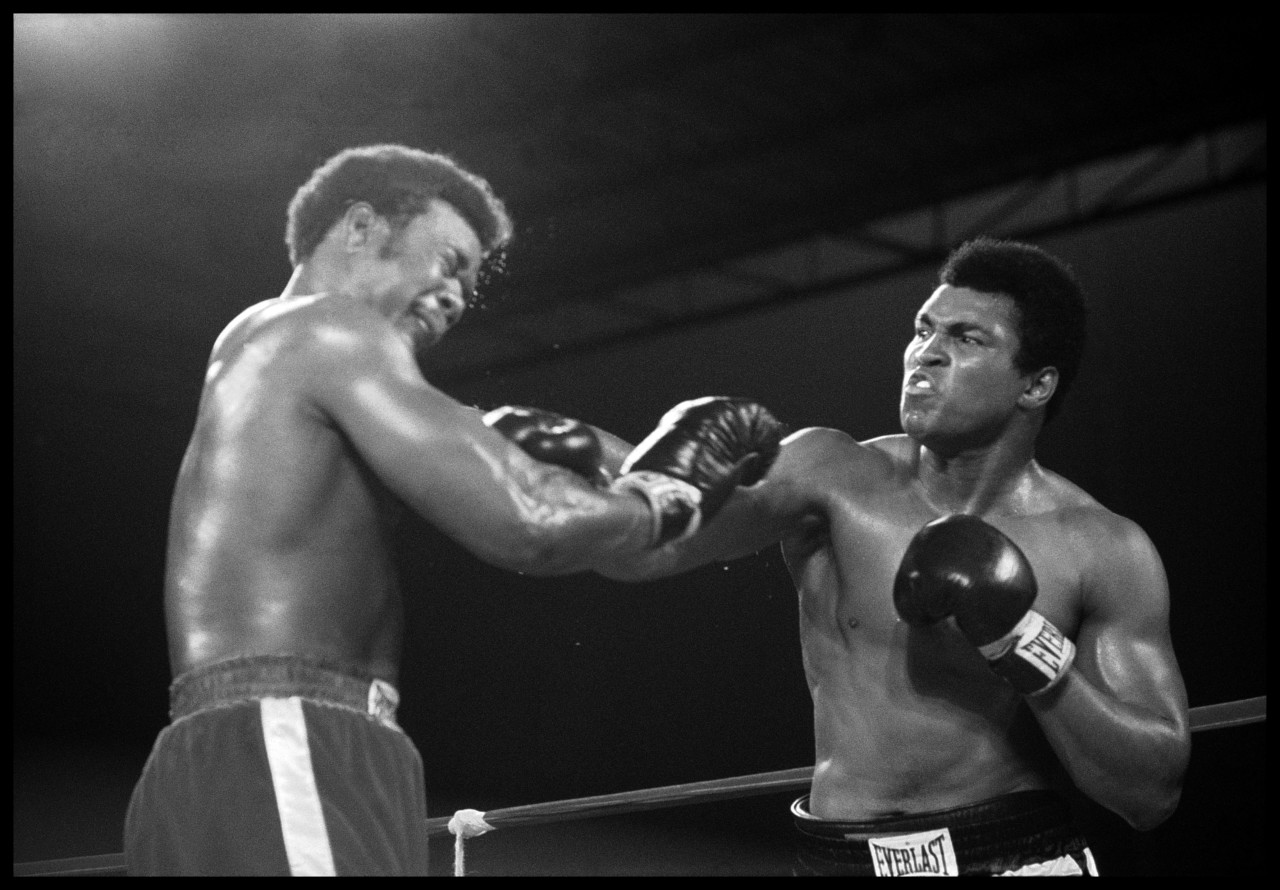

In addition to the politics represented in the curation, Sealy includes important moments of what he calls African “soft power”, whether exerted by musicians like James Brown and Nina Simone, or by the famous Rumble in the Jungle – the boxing match between George Foreman and Muhammad Ali, which took place under dictator Mobutu Sese Seko’s rule in Zaire in 1974, and was watched by an estimated billion viewers worldwide.

“Muhammad Ali, at the time the most important sportsman in the world, is fighting George Foreman, who is probably seen as a boxing version of Mobutu himself in the ring, crushing everyone in front of him,” explains Sealy, who argues that Ali’s victory represented something significant in terms of ideas of freedom and liberation. Ali, who rejected the draft to fight in Vietnam becomes representative of a wider, post-colonial or anti-imperialist narrative.

Tourism in Africa

Sealy chooses Martin Parr’s work documenting white tourists in Africa to explore “the European idea of tourism and the tragedy of those kinds of entanglements and the power relationships that are at play.” Parr, who has photographed tourists all over the world as part of his practice, captures these holidaymakers engaging with African culture at surface-level, while the inclusion of cameras around the necks of some are a tacit reminder of how vernacular holiday snaps also add to the propagation of a certain kind of understanding of African culture in the West.

Power and Consequences

The curation in this project aims to look beyond single, stand-out images and explore new narratives. “What I am not trying to do is find ‘decisive moments’ in these works, I am trying to find works that open up stories,” explains Sealy. But, what the curation really points to is what resonates outside of the frame. Though Sealy is able to draw out a different perspective on Africa than has traditionally been propagated, what his work on this project has highlighted is how few of these potentially alternative views were photographed, and what that says of the power structures that have directed the display and commissioning of photographic images.

“It’s interesting that if this is a snapshot of the world’s photographic archives in terms of trying to find a positive image of the continent, then there’s not that much there,” says Sealy, “Because what drove most people to the continent was its turbulence, rather than trying to find stories that are really celebratory. What this speaks of is the way photographers where conditioned to work and what they were commissioned to produce by publishers, what was designated as being of public interest at the time.”

More than the aesthetic value of an image, Sealy asks deeper questions around the effect the images have on culture; “I always ask a key question: what’s the work actually doing,” he says, stressing the seriousness of these real-life consequences. “[Photographers] produce ideology,” he explains, referencing the late African-American photojournalist Gordon Parks’ key text My Camera is a Weapon. “Images can kill and destroy lives, or they can celebrate them,” says Sealy.

Call-out for New Perspectives

Magnum Photos and Mark Sealy want this curation of images to serve as inspiration for contemporary photographers to respond to, and are asking photographers to submit their own work.

Four grants will be allocated to early-career South African photographers to respond to Mark Sealy’s curation of the Magnum Photos archive by making new photographic work in response to themes in the selection. Two of these grants will be available on application via an open submission process, and two of these grants have been awarded through Magnum’s ongoing relationship with the Of Soul and Joy project; a workshop and talent development program in Johannesburg, South Africa.

For full details on the grants available, and to apply, go here.