Southall Resists

Forty years ago, residents of a London suburb took to the streets to protest against racism. Two activists working with the legacy of these events reflect on the importance of archival images in recording underrepresented histories

On April 23, 1979, the far-right National Front (NF) party held a meeting at the town hall in Southall, an area of suburban London with a large South Asian population. The party had, for some, time been organizing activities in areas with large ethnic minority populations in order to gain publicity for their campaigns. A demonstration against the NF took place in Southall involving local activists, community members, and anti-racist groups from across London.

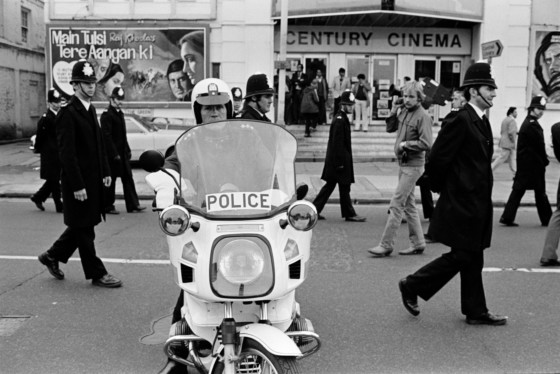

A large number of police were ordered to the area in order to contain protestors, who the authorities feared would incite violence. In the clashes that followed between 3,000 protestors and 2,800 police officers, hundreds of arrests were made, and 64 members of the public were reported injured. One man, a left-wing activist and teacher named Blair Peach, died of a fatal head injury during the clashes. Peach’s injury, according to sources at the time, was thought to have been caused by a police officer. This was supported by the subsequent Cass Inquiry’s findings which were published in 2010.

Magnum photographer Chris Steele-Perkins was in Southall on Saturday April 28, 1979, to capture the events which followed the death of Blair Peach. Suresh Grover is a founding member of the Asian Youth Movement in Southall, one of the groups which organized the demonstrations on April 23 and 28. Together with Jagdish Patel, he presently runs The Monitoring Group, a human rights group which works challenging discrimination in policing. We spoke to Grover and Patel about memories of April 1979, recognizing fellow community members in the photos, and the affirmative role that photography can play in how history is recorded.

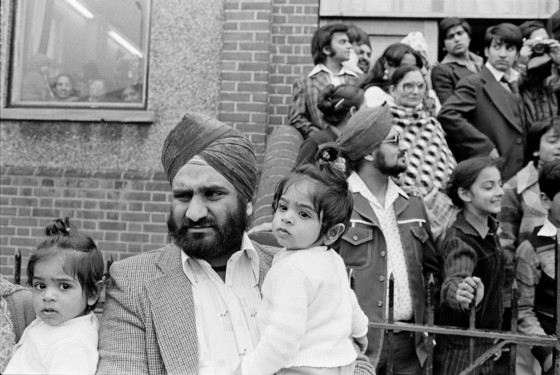

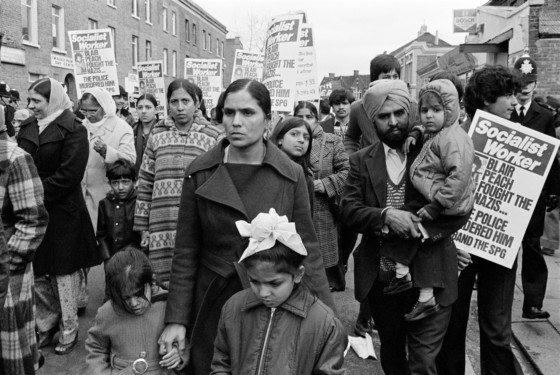

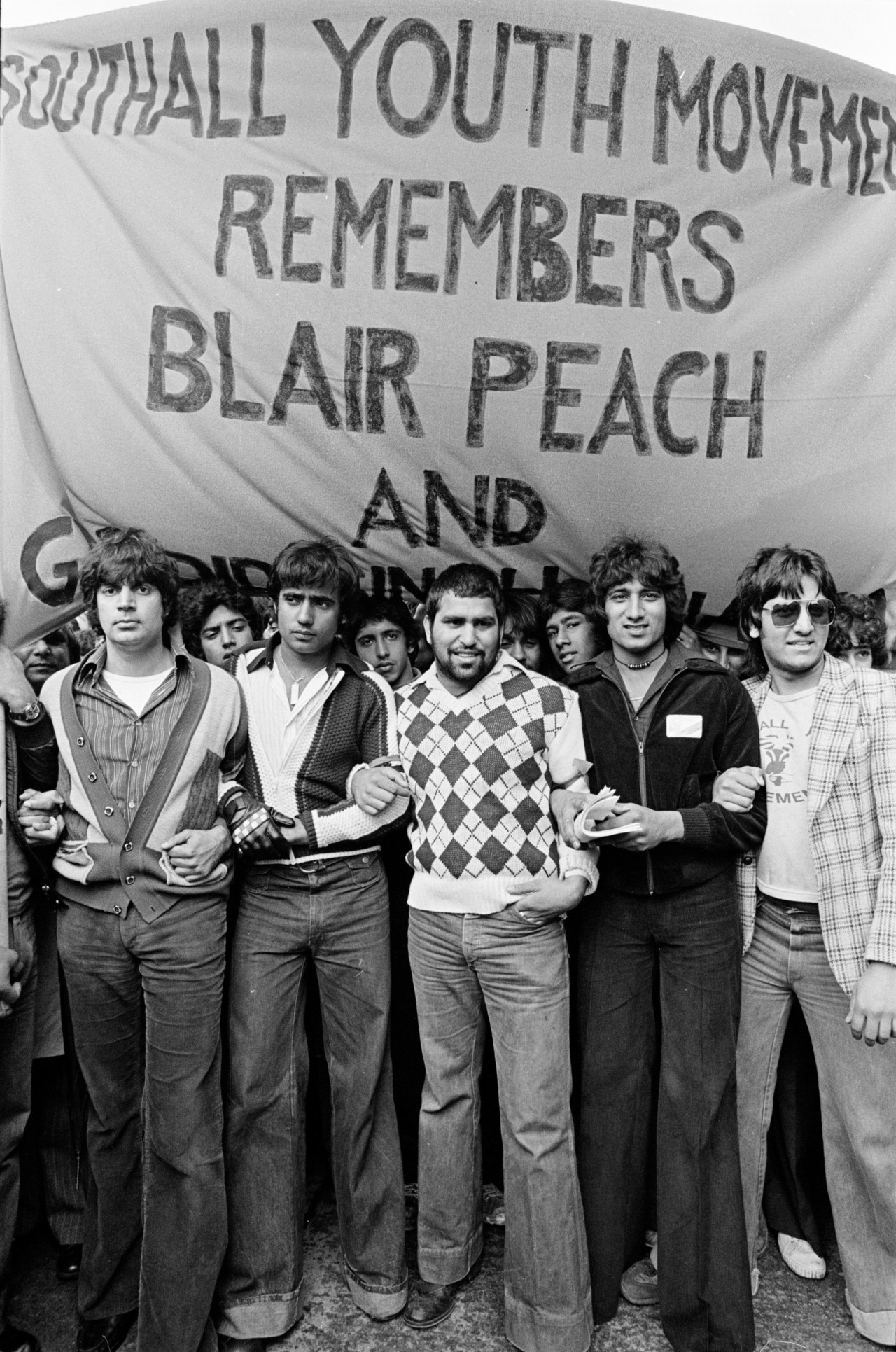

“The photographs I can see are about the demonstration after Blair Peach was killed. It’s Saturday 28th. I think there were over 20,000 people,” says Grover, “There was a sea of empathy for Blair and for other victims of April 23. These people had come out to express their anger and their show of strength.”

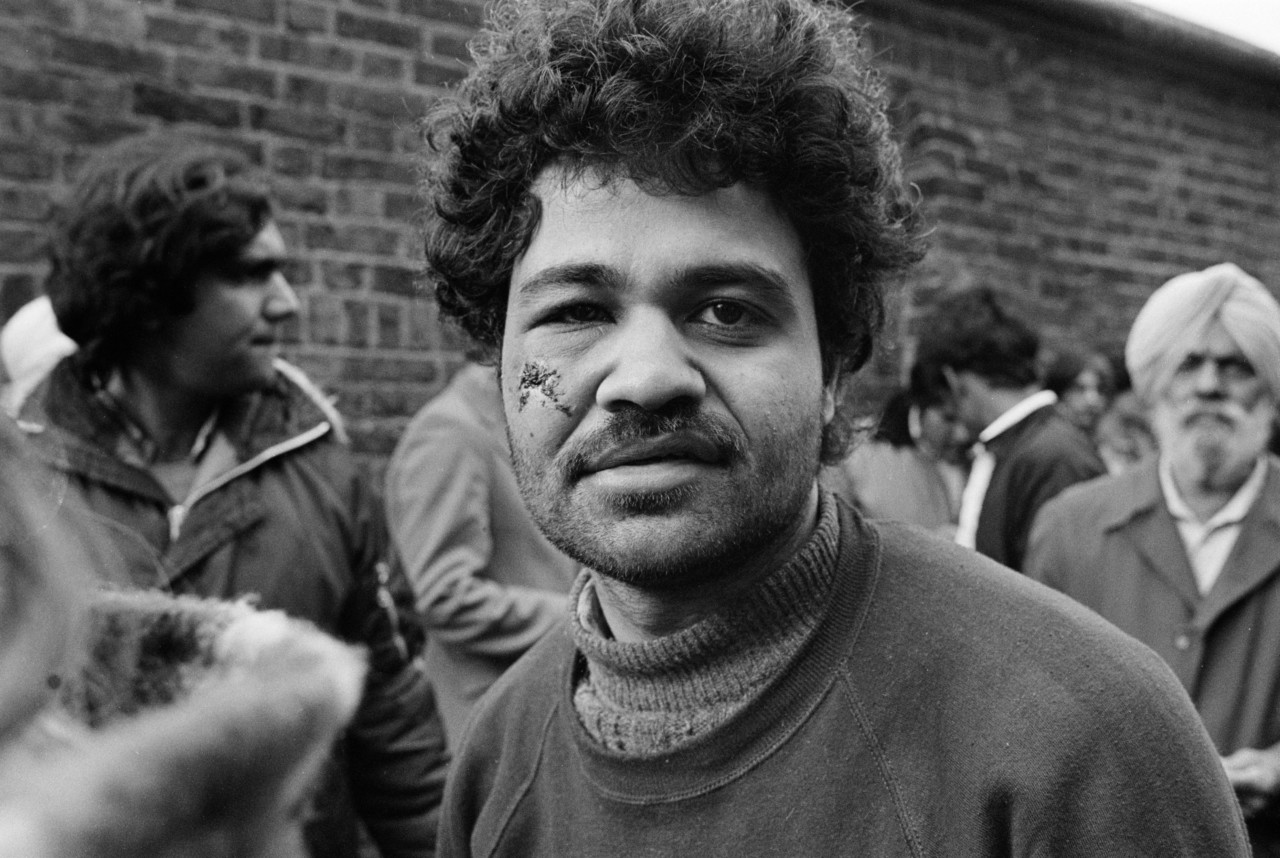

Grover points out the people he recognizes in the images. “You have a photograph of a young man, curly hair, with an injury on his right eye. That’s Sunil Sinha, one of the leaders of the Southall Youth Movement. On his right is a young Pakistani man who was the coordinator of Southall Rights Paralegal Centre that had been organising with the Southall Youth Movement.”

Grover identifies two women in a photograph who carry a banner for the Southall Women and Girls Association, a welfare association set up more than a decade prior to the Asian Youth Movement. “This woman, Lakhbir Bains,” Patel points at the woman wearing a plaid coat, “tells a story that she met a policeman who told her to go back to where she came from. And she says ‘Well I live over there and you won’t let me go home!’”

Tensions between the state, the far-right, and local communities in Southall had been building for some time. “Blair Peach’s murder cannot be understood unless you understand what happened in Southall a couple of years beforehand and a couple of years after,” says Grover, “A series of events which started with the murder of Gurdip Singh Chaggar on the 4th of June, 1976, right in the centre of Southall where everybody felt they were safe, which galvanized young people to come out on the streets and organise themselves.” Chaggar was a local teenager who was fatally stabbed in a racist attack, prompting the then-leader of the National Front to make the statement: “Last week in Southall, one n***** stabbed another n*****. Very unfortunate. One down, a million to go.”

"You can’t really build the future unless you acknowledge the past and present."

- Suresh Grover

The demonstrations against increasingly public displays of racism, against the killings of Chaggar and Peach, and against targeting by fascist groups, were a way for the community to stand in resistance to the terrorization they felt they faced. “There is a myth created about Asian communities as being docile — unable to fight and resist racism — when actually our tradition has been that we will always fight against injustice, to finish off the British Empire in India and other parts of Asia,” says Grover, “We’ve kept that tradition in this country and nobody has acknowledged that historically, including the left, properly. So that’s why these pictures and the events of 1979 are very, very pivotal to our own history of the Asian, the black, the brown — the history of people of colour across the country.”

Grover and Patel highlight that photography is very important in telling the story of a community. “If you look at the newspapers in ‘79 they immediately called it a race riot. And the photographs that were used [were of] Asians being aggressive,” Patel says. But delving further into a story can illuminate aspects of events that may not have been depicted in media coverage in the past. “If you look at this photo from Chris [Steele-Perkins] for example. It’s a suburban street, semi-detached houses.” Patel covers up half of the photograph. “If you look on this side, it’s a normal family sitting on the wall with their kids all dressed smartly. But suddenly,” he says revealing the rest of the image, “you have a whole street full of police officers. It’s that militarization of a town in that period of time, that just comes across, which you’d never see in the newspapers at the time.”

"It’s that militarization of a town in that period of time, that just comes across, which you’d never see in the newspapers at the time."

- Jagdish Patel

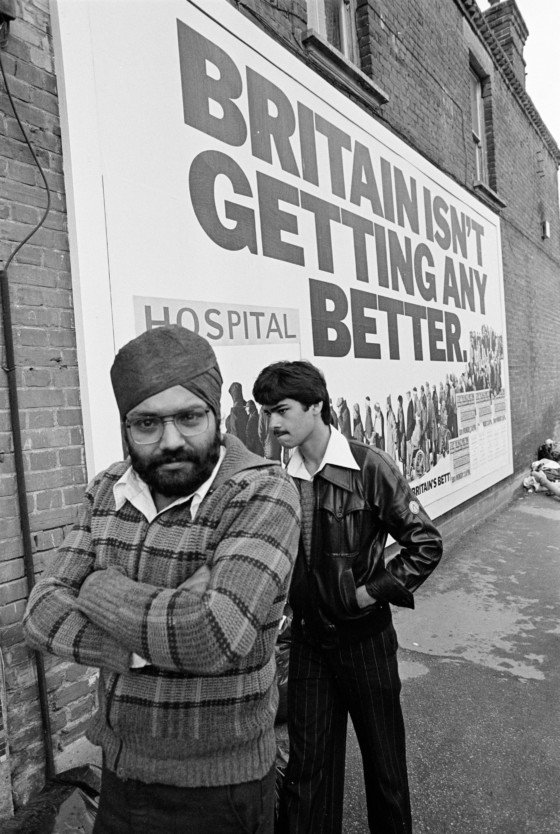

The issue of immigration is as relevant now as it was in the 70s. On this subject, photography has a key responsibility in influencing people’s perceptions, says Grover. “People are very conscious about photography, certainly in my family or our communities, because you feel a minority always in this country, and whenever there are elections there’s always the issue of immigration. It’s not recent. Every election since 1966 — since I’ve been here — has been about immigration. A simple photograph people love, because it acknowledges your presence. And if you distort that presence people get very angry. So that acknowledgement of being just simply present, or being omitted, becomes an issue for people,” says Grover.

“The fact is that the early migrants came to rebuild Britain in a post-war economy, but never got the benefits of it. They serviced the hospitals, they swept the streets, they worked in the foundries…. That needs to be depicted in an archived way. It’s really never done and that’s what we are moving towards. You can’t really build the future unless you acknowledge the past and present,” says Grover.

Proof of the existence of immigrant lives is not the only type of evidence that photography provides. Individuals involved in the protests in Southall were acquitted of charges they were not guilty of as a result of photographic documentation. “Clarence Baker, who was the manager of [reggae band] Misty in Roots, the founder of People’s Unite [a community center in Southall], a Rastafarian, a totally peaceful person, was beaten so brutally that he had to spend three months in intensive care. He could have died. And he was actually charged with violent disorder. The police claimed that he was wearing an army uniform and shouting ‘kill the pigs’ — Clarence has never ever used those terms. It’s only because of the photographs that existed that we could show that Clarence was not in an army uniform. It’s only because videos also showed he was telling the police to remain calm, ‘this is peaceful demonstration’ — that the charges against him were dropped. If there was no evidence he would have spent years in prison.”

Did Grover and Patel think that attitudes had changed in the last four decades? “It really angers me that the black presence has been here for a long time and it never really gets acknowledged until someone dies or a terrible event takes place, and you have to push the authorities to do that. […] It’s not a question of what color you are, what ethnicity you are, you can sense moments regardless of who you are, if you believe in humanity,” says Grover.

“One of the ways you can have a discussion [about how people are represented] is by asking the people who are actually in the photographs to tell the story from what they see.” says Patel, “And [in 2010] the police acknowledged they used excessive force, that Blair was probably killed by an officer. That many years it took.”

Alongside other local activists and artists, the pair are currently organising Southall Resists 40, a season of events commemorating and memorialising the events of April, 1979. Their aim is to raise awareness of issues that their community, and the country more widely, continues to face, through exploring the educational value of photographs like Chris Steele-Perkins’. But the value of the photos lies not just in cultural or educational applications. “I think photographs can reflect life as it is, or was then, as lived experience.” says Grover. “I think there is a narrative in every photograph. In the mainstream, when it looks at migrant, immigrant, or black presence generically, in this country, 9 out of 10 times that narrative is very negative. There’s still an image of Southall as a place white people can’t come to, that it’s run by black or brown people, that it’s violent, it has riots. Southall is one of the few areas where kids will be walking down the street and they’ll feel safe. It’s very family-oriented. So [in mainstream media] it’s not what is in the photograph that is important. It’s actually the absence of things in it. What photography [of our real experiences] does is actually bring to life the other half: our presence.”