Raymond Depardon’s Paris Dakar Rally

As the Dakar Rally enters a new era, we look back on Raymond Depardon's photographs from the event's 1990 staging

The Dakar Rally begins a new era on January 5, 2020, when the gruelling off-road race is staged in Saudi Arabia for the first time.

First run during the winter of 1978-1979, the event’s reputation was built during the years up to 2007, when the race was contested between the respective capitals of France and Senegal. It was thus known as the Paris-Dakar and, when the French city ceased to provide the starting point, it became simply the Dakar.

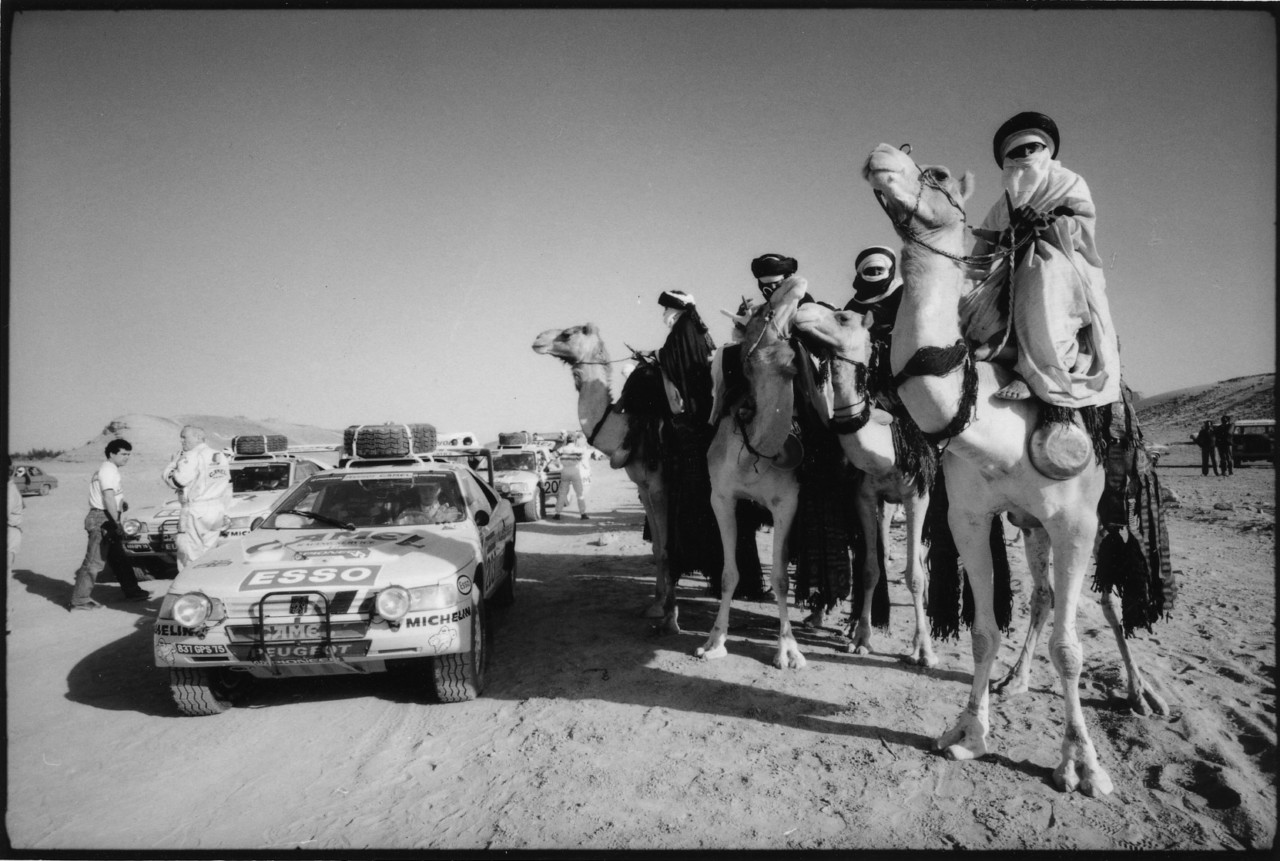

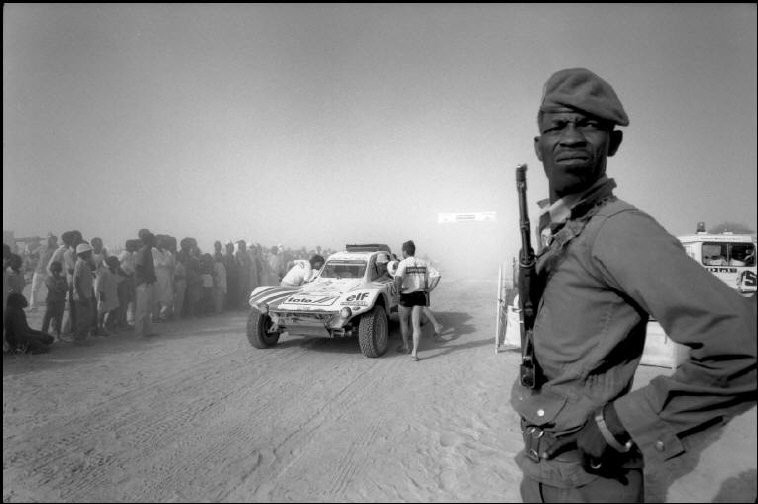

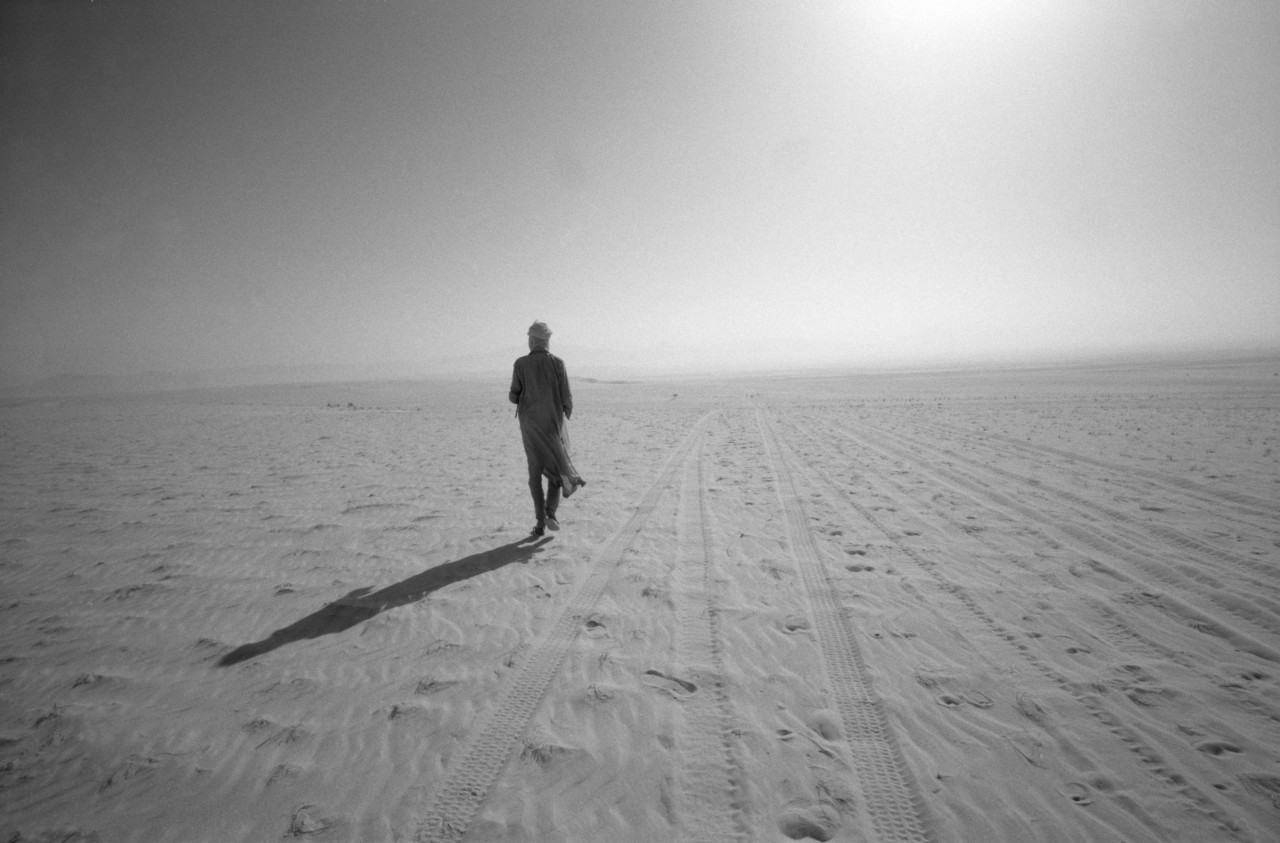

Within its first decade, the rally was transformed from a one-off adventure for a group of French thrill-seekers into a major fixture on the international sporting calendar. The Dakar became Formula 1 in the desert, with world-famous drivers and riders taking the wheels – or handlebars – of vehicles decked out in the colours of tobacco brands. Raymond Depardon‘s photographs, which show these machines alongside camel riding Tuareg nomads, capture the meeting of two diametrically opposed worlds.

"Competitors describe [the desert] as a living being, the shifting dunes and sudden sandstorms akin to dramatic mood changes"

-

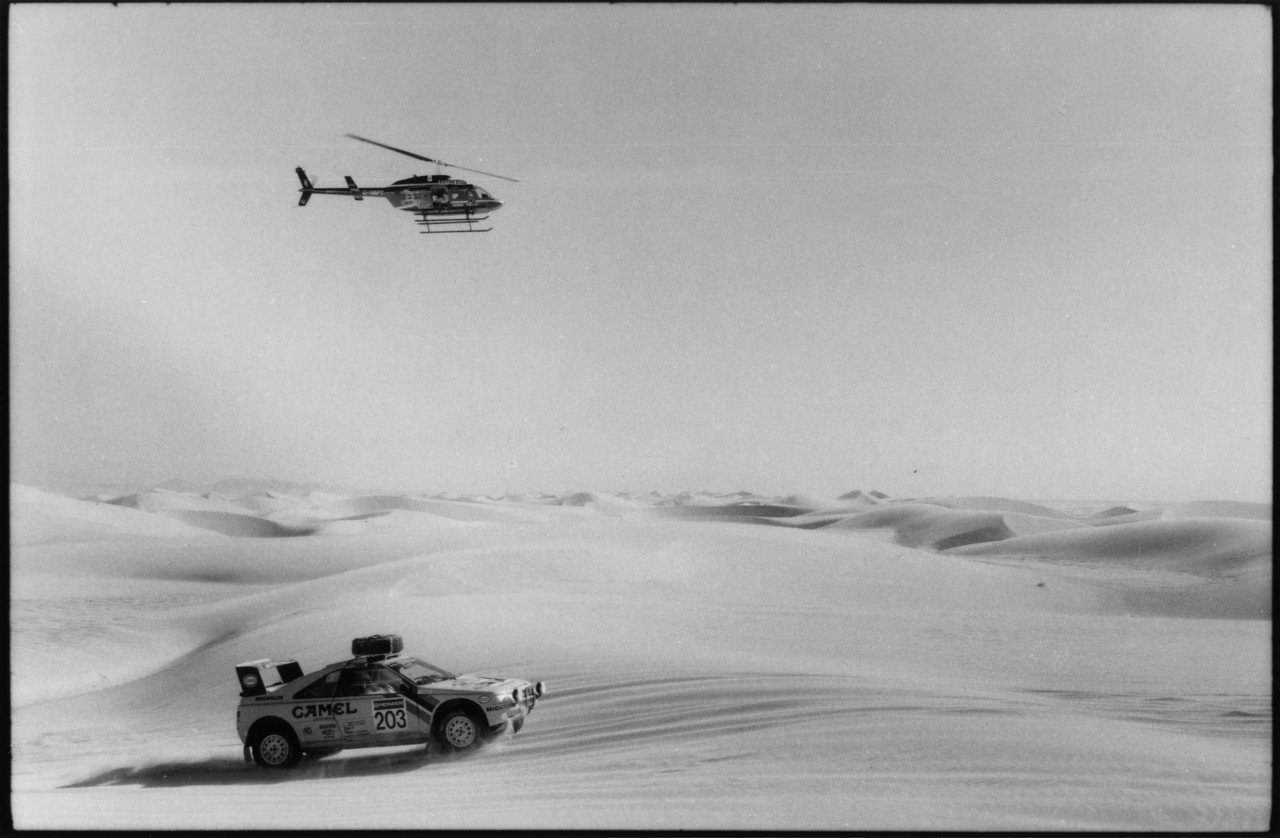

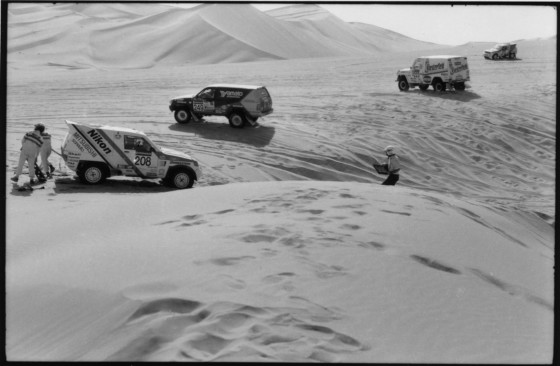

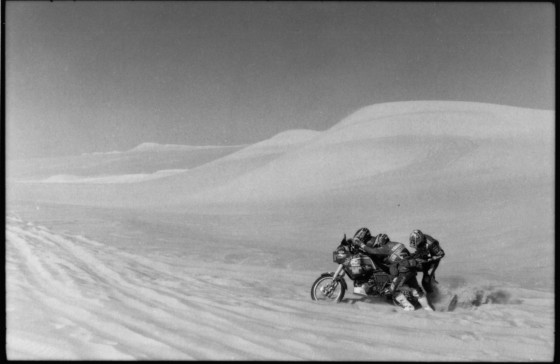

Though the location shifted to South America in 2009, the Dakar name stuck, the desert providing a tangible link between each of the race’s iterations. Competitors have described the desert as a living being, the shifting dunes and sudden sandstorms akin to dramatic mood changes. There was, in the event’s earlier iterations, a sense of solitude that is vanishingly rare in major sporting events, encapsulated by Depardon’s images of disconsolate motorcyclists pushing their stricken machines, or abandoning them altogether.

The race was conceived by Thierry Sabine, a dashing and bright young Frenchman from a well-off family. Contesting a rally between Abidjan and Nice in 1977, Sabine became lost in the Libyan desert. Close to death from exposure when he was finally rescued, he had fallen in love with the inhospitable landscape. Sabine resolved to stage a rally where losing oneself in the desert was the objective, rather than an unfortunate mistake.

On the day after Christmas, 1978, the inaugural Paris-Dakar began. The assortment of vehicles included little Renault 4s and Range Rovers temporarily withdrawn from farm duties, while the competitors were largely amateur adventurers like Sabine. Motorcyclist Cyril Neveu won after a three-week, 10,000-kilometre trip into the unknown.

"Back in wintery Europe, images of breathtaking Sahara scenery and nomadic tribespeople captured imaginations. Aided by Sabine's knack for PR, the Dakar was an immediate hit; by the early nineties the rally was reaching its zenith"

-

Back in wintery Europe, images of breathtaking Sahara scenery and nomadic tribespeople captured imaginations. Aided by Sabine’s knack for PR, the Dakar was an immediate hit; by the early nineties the rally was reaching its zenith.

Soon, the privately-entered Range Rovers and Renaults had been replaced by cutting-edge machinery paid for by major automotive manufacturers. World Champion rally driver Ari Vatanen won the 1990 event, his third in four years, driving a Peugeot 405 T16 that had been created specifically for the desert.

Sabine would not live to see this. Searching for a group of vehicles in a sandstorm during the 1986 event, his helicopter had crashed into a dune, killing all five people on board. This put the Dakar’s death count at 15, a number that has continued to grow since, and had reached 70 by the end of 2016.

The loss of competitors was grim but could ultimately be accepted: they knew the risks and participated of their own free will. Arguably, the Dakar’s darker side was revealed by the destruction it could wreak on innocent lives. Spectators and bystanders have also been killed in accidents and collisions involving racing and support vehicles, while livestock and crops along its route were destroyed.

"As the event grew bigger, it seemed to lose touch with its host. Conceived as the star, Africa was becoming little more than a stage"

-

Questions were asked about the environmental damage caused by many hundreds of vehicles – including competitors, support crew and media – descending on a continent known for its fragile ecosystems. As the event grew bigger, it seemed to lose touch with its founder’s proclaimed love of the desert. Conceived as the stars, the dunes of the African Sahara and Sahel were becoming little more than a stage.

There was no shortage of criticism as the event grew: the Vatican newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, called the rally a “vulgar display of power and wealth in places where men continue to die from thirst and hunger”, the same paper dubbed the event “the bloody race of irresponsibility.” Some critics believed that former colonists were treating the countries which the rally passed through as little more than playgrounds. Senegal had been under French control from 1677 through 1960 and, from 1902, Dakar had been the capital of French West Africa. French musician Renaud sang about “500 connards sur la ligne de depart” (500 assholes at the starting line).

Sabine seems to have been genuinely passionate about the desert and was keen for competitors to experience it and support its inhabitants by buying supplies locally during the race. In his absence some efforts were made to give something back, with a number of water pumps installed to improve irrigation in villages along the race’s route – a move that may have come about sooner had the event’s founder lived long enough and which was dubbed as little more than tokenistic by the event’s critics.

When the Dakar finally left Africa, it was due to security fears: four French tourists were killed in Mauritania on Christmas Eve 2007, leaving organisers with no choice but to cancel the 2008 event. In 2009 the Dakar was reborn in South America. From a sporting perspective this proved largely successful, though environmentalists and indigenous peoples spoke out here too against the impact of the event. In 2019, with Chile refusing to participate, the race was staged solely in Peru.

The Dakar clearly retains some of the appeal of its heyday: the 2020 edition will see the debut of two-time Formula 1 champion Fernando Alonso. The event’s success owes much to its years spent traversing Africa, the continent remaining a powerful component of the event a decade after it left. Memories of those first rag-tag forays into the unknown continue to draw the brave and the wild, while the glory years of the eighties and nineties add prestige, explaining the continued use of the Dakar name and the event’s iconic logo, a likeness of a veiled Tuareg nomad.

While the move to Saudi Arabia might sidestep issues regarding indigenous rights in Chile or questions around neo-colonialism in Africa, the fresh charge of ‘sportswashing’ has been raised in relation to the event’s new setting. The act of moving is not a problem in itself – like the Tuareg, the Dakar is seemingly a nomad, its only home the desert.