The Spirit of the Game

Trent Parke's return to exploring cricket in India, 24 years on

Having travelled with the Australian national team to the 1996 Cricket World Cup in India, on assignment, Trent Parke recently returned to the country with the former Australian team captain Steve Waugh, to help him make a book and documentary on the ‘spirit of cricket’. Shooting personal work during trips between filming locations, Parke was taken aback both by changes in the country, and by its enduring adoration of the game. Here the photographer discusses the sport’s pivotal place in Indian popular culture, his doubts about returning to the nation to work, and a new book project that has sprung from the images he made from the windows of moving cars as he criss-crossed the country.

For those who are not quite up to speed on cricket – who is Steve, and how important is cricket how important is cricket — to you, and also in Australia, and in India?

I have always had two main passions in life, photography and cricket.

Cricket in Australia is the national summer sport and is played by more than a million people. Cricket in India is a religion and it’s played by almost everyone! India accounts for 90% of one billion cricket fans worldwide. On the cricket field, Australia and India have a fierce rivalry.

I first travelled to India in 1996 with the Australian national team to cover the 1996 Cricket World Cup, working as the sports photographer for News Ltd papers. We landed in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and I had immediate culture shock. I was young and it was like nothing I had ever seen or experienced. We were mobbed by masses of people the moment we set foot in the city. Stray cats and dogs and animals roamed the streets, and the level of poverty was incredibly confronting. I struggled to leave the hotel for days.

Steve had organized to meet Mother Teresa (now Saint Teresa) at one of the Missionaries of Charity sites, and I was asked to go along to photograph. It was an incredible moment, like walking onto a movie set and that was kind of where it all started. From that point on, as we toured the country with the Australian team, Steve and I would organize early-morning sightseeing ventures to try and experience more of the country and the people. But everywhere we went we would be in an armed convoy as security was very tight and armed guards would exit the vehicles before us, clearing the areas and defeating the purpose of the outings, which was to try and see life as it really was.

"I struggled with many aspects of that trip. It was six weeks of extreme pressure, insane deadlines, continual illness, terrible phone connections for transmitting (that was pre-mobile-phone days) and all the problems associated with using film on deadline.

"

- Trent Parke

How did the recent trip to India with Steve Waugh come about?

Steve Waugh is a legend of the game. He is considered the most successful test captain in history [test cricket is generally considered the spot’s apex, with gruelling matches that last five days or more], and was one of the leading batsmen of his time, scoring over 10,000 runs. He is known as one of the toughest competitors to play the game.

One Sunday at 7.30 am I was driving in the countryside to a cricket-coaching clinic in the bush, when Steve Waugh’s name flashed up on my phone. I had watched him in England on TV only the night before, mentoring the Australian cricket team during the Ashes contest.

He was to the point, as usual: “Trent, do you want to come to India with me to help me make a book on the spirit of cricket?”

Having just mentored the Australian team in the art of cricket, he was now asking me to mentor him in the art of photography. At first I was reluctant: the difficulties I had experienced trying to work and cover the 1996 World Cup came flooding back.

I struggled with many aspects of that trip. It was six weeks of extreme pressure, insane deadlines, continual illness, terrible phone connections for transmitting (that was pre-mobile-phone days) and all the problems associated with using film on deadline. Most times I would have ten minutes at the game to shoot a picture worthy of a front page before having to leg it back to the hotel, assuming we had one! It wasn’t always the case due to the fanatical crowds and overbooking. I would have to heat up the tap water to exactly 37 degrees to process the color negatives in the bathroom, dry the films with a hairdryer and then try to transmit the color separations on a huge Lefax machine back to Australia while the phone lines dropped out every few minutes and I would have to start transmitting again. Sometimes it took eight hours just to get one separation through… and all the time, the editors in Australia were screaming for the pictures. It took me a long time to recover from the trip, physically and mentally. I doubted I would tour India again.

"We travelled the country over 18 packed days of exploration searching for anyone with bat and ball, from the beaches to the mountains, the desert and the cities."

- Trent Parke

What convinced you?

Steve can be very persuasive. In the end I agreed, and I’m glad I did.

The Indians play with unrivalled passion and freedom. They love it. They play the game in a way that’s always exciting. Stumps are only ever placed in the ground so far, so that when bowled [hit by the ball] they cartwheel backwards forever. Boundaries are always small so that more 4s and 6s [high scoring hits that carry the ball over the boundary of the field] are struck. And they find a way to play, no matter what the environment or circumstances, or their social status.

It was that last aspect that continually intrigued and excited me. As Steve says, all you need is a bat, and a ball, and imagination.

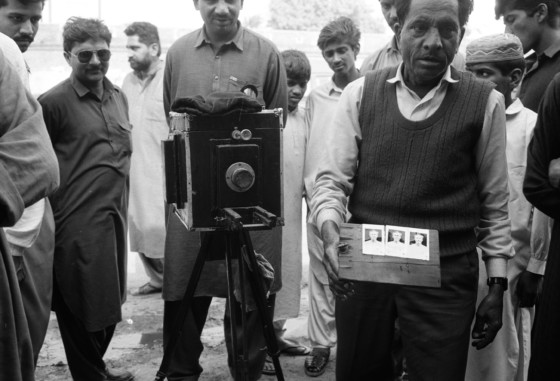

The country has changed so much since 1996. It was like being in a time machine, particularly as we visited many of those same locations from 24 years ago. We travelled the country over 18 packed days of exploration searching for anyone with bat and ball, from the beaches to the mountains, the desert and the cities. We watched them play in the streets, by the rivers, and in the fields of the countryside. From playing with a three-year-old Instagram prodigy on his rooftop, to palace cricket in the royal ballroom with a king, we experienced the game from all levels, and at extreme ends of the scale. And that’s what strikes me about India the most. All around, you have this collision between the old world and the new world, in a land of extremes.

What was it you were doing there – day to day – in terms of your role in the making of the doc, and making of images?

Just to be clear, it was not my documentary. We were accompanied on the trip by cinematographer Andre Mauger who filmed behind the scenes and all the action. The footage was then given to ABC, who then made the film… The film concentrated on me teaching Steve to photograph, and of course the cricket.

What were the most impressive, or hard-hitting points of your trip? And what aspects were perhaps most removed from your expectations?

There were so many highlights. Every day I would sit back at the end of it and think that was the best day of the trip… But they just kept coming. One day would outdo the next. I came across so many forms of the game I have never seen before. So many people playing cricket, everywhere you look. Girls and boys, women and men. Giant billboards of former players adorn many city street corners. Huge stadiums rise out of unexpected places. The game is everywhere, all-around. India is cricket.

To get off the bus after a long road trip and have the sun shining on a team of monks playing cricket, with the ice capped mountains of the Himalayas as a backdrop, it just doesn’t get much better than that. And those monks were serious athletes and tremendous players. Tough as nails. Playing on a cow paddock (with cows in place), no protective padding and hard cricket balls, belting them all over the place. One guy was hit in the face with a bouncer [an aggressive type of bowl where the ball pitches up toward the batsman’s head] and hardly flinched. We watched as a huge egg of a bruise – like something from a cartoon – formed on his face. He just shrugged it off and kept batting.

"If you ever need inspiration, look no further. Some of the players, with only one arm or one leg, or with other challenges had found a way to play. And not only play, but to excel."

- Trent Parke

Photographing and admiring the skill of India’s World Cup-winning, physically challenged cricket team was also pure joy. They are — once again — incredible athletes, and if you ever need inspiration, look no further. Some of the players, with only one arm or one leg, or with other challenges had found a way to play. And not only play, but to excel. Bowling seriously quick deliveries, using the assistance of a crutch to balance and propel themselves. They had incredible fitness and strength, and played games that were so demanding on the body as well. They were hitting sixes with one hand. Just amazing.

One one of the most surreal days of my life saw me bowling to the King of Baroda, Maharaja Samarjitsinh Gaekwad III (who was once a very good cricketer) as Steve took photographs. We played cricket in the Royal Ballroom of Lukshmi Vilas Palace, surrounded by priceless and irreplaceable vases, sculptures, and paintings. There was one rule… Keep the ball along the ground and don’t break anything! Suffice to say, the queen wasn’t the most relaxed person in the room!

I remember the bat and ball factory in Meerut: watching the skill and precision craftsmanship that goes into hand-stitching every cricket ball. Everything there they made from scratch, from the tanning of the leather all the way to finished product. It was five floors, manufacturing cricket equipment on an epic scale. Such is the need to fill the huge demand.

"On a single oval at any given time a hundred different games of cricket can be taking place. Bats and balls are flying everywhere, and fielders are constantly running every which way in what can only be described as organized chaos."

- Trent Parke

How have technological advances changed the way cricket exists in India?

One of the amazing things I love about sport is that if you have serious talent you can make it as a professional athlete no matter where you are.

With the rise of the Indian Premier League, millions upon millions of dollars are to be made. One of the biggest notable changes from the pre-mobile-phone days of 1996 is the rise of digital technology. This has opened up the sporting world and suddenly kids living in poor and rural areas with normally little chance of being seen are being found and promoted through the use of social media.

Cricket gives them hope, a chance of a better life. Parents will go to extreme lengths to have their child seen. We visited a three-year-old Instagram prodigy on the outskirts of Kolkata, whose parents had enclosed their rooftop with netting to allow him to practice. On one Instagram post alone he had over 600,000 views.

On a single oval at any given time a hundred different games of cricket can be taking place. Bats and balls are flying everywhere, and fielders are constantly running every which way in what can only be described as organized chaos. The Oval Maiden in Mumbai is such a place. The great Indian master batsman Sachin Tendulkar grew up playing his cricket there and said if you can find the gaps with a hundred players on the field, international cricket and big stadiums, with only eleven fielders and plenty of space becomes easy.

"I became obsessed with the world outside the bus window and I shot the entire time, day and night. I couldn’t believe how much the country had changed since I covered the 1996 World Cup, and I kept having this sensation: I was looking at what the world may have looked like in the past, but what it also all may look like look like in the future"

- Trent Parke

What do you plan to do with the work you made yourself while in India?

In between the cricket, we travelled by bus on long road trips, which I found utterly fascinating. I became obsessed with the world outside the bus window and I shot the entire time, day and night. I couldn’t believe how much the country had changed since I covered the 1996 World Cup, and I kept having this sensation: I was looking at what the world may have looked like in the past, but what it also all may look like look like in the future. Humanity with all of its excesses, and waste, and dwindling space.

Sometimes I felt like was traveling through a war torn landscape, the result of the ‘over-population bomb’. Other times I felt like I was watching a strange, alternate version of America, or Australia even. It’s hard to explain, but I felt like I was removed from it all, a spectator, or an alien in a flying machine, slicing through moment upon moment in time…

This work is something that I am exploring more now in book form: the collision between the old and the new world. The class difference between the rich and poor, the rise of the middle class. Cultural homogenization. The technology boom. Digital India. The mobiles and modern cars. The visual clutter of advertising everywhere: CEMENT, STEEL, COKE, PEPSI, FAST INTERNET…All of this amidst the constant noise and pollution of a country on the move… The random chaos. I couldn’t take my eyes away for fear of missing something, I did not want the bus journey to end.