Syria: The Aftermath of December 8

Emin Özmen, who has been documenting the Syrian Civil War since 2012, travels to Damascus to cover the fall of Bashar al-Assad for French newspaper Libération

Following the fall of President Bashar al-Assad’s government on December 8, 2024, Emin Özmen has been in Damascus documenting the aftermath for the people of Syria on assignment for the French newspaper Libération.

Arriving in Damascus on December 13, Özmen first photographed the mass gatherings in the city’s Umayyad Square, as people celebrated the end of over five decades of the brutal Al-Assad regime. His images show moments of joy and elation as groups hold the Syrian flag of independence and its three red stars high — an act that would have been unthinkable only one week earlier under Al-Assad’s rule.

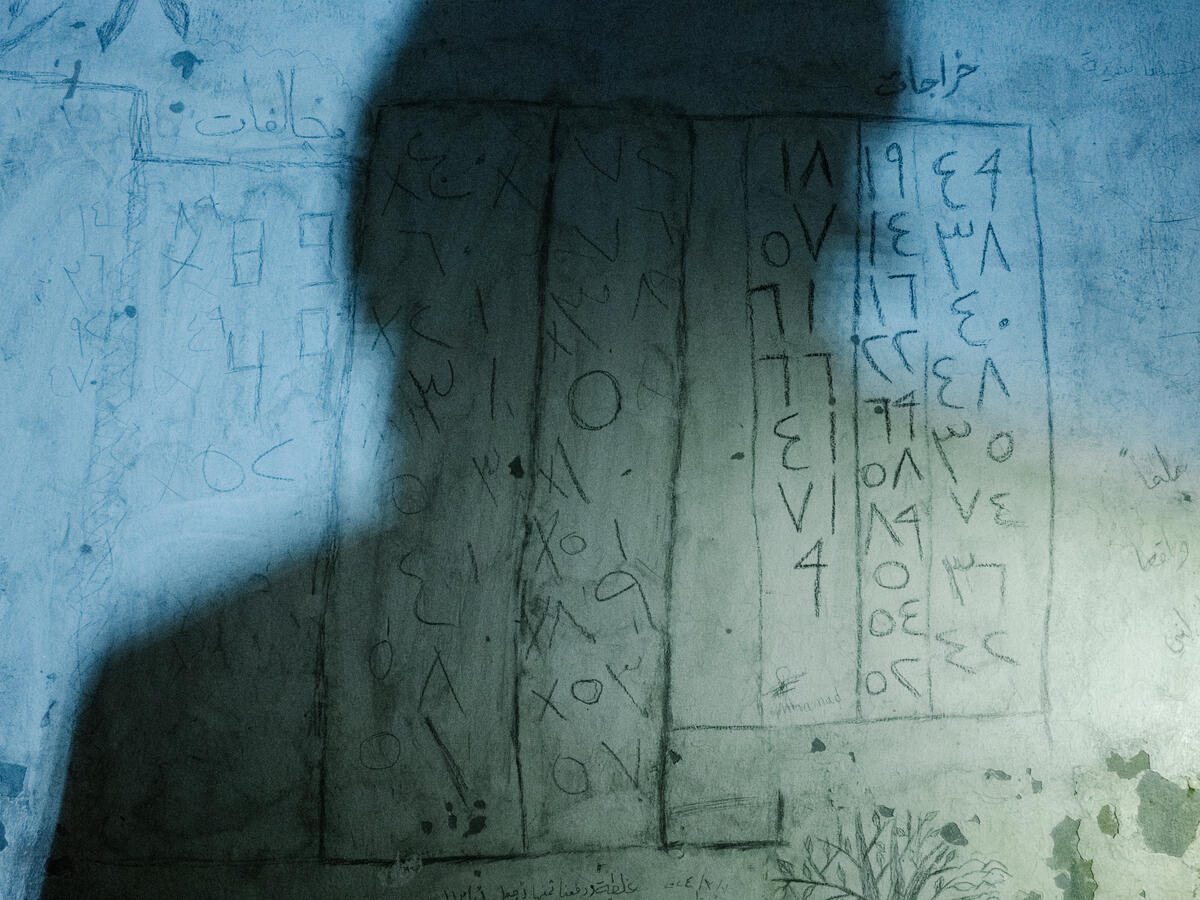

Accompanying Libération journalist Luc Mathieu, Özmen then traveled to Yarmouk, a Palestinian refugee camp located only eight kilometers from the center of Damascus. Home to Syria’s largest Palestinian refugee population before the war broke out in 2011, the district has now been almost entirely destroyed. Once home to over 150,000 people, most were forced to leave amidst violent clashes between the Syrian government forces and opposition fighters over the past 13 years.

Only several thousand live among the ruins now, according to Libération, with homes in ruins and no access to basic services such as electricity and water. Following the fall of Al-Assad, several begin to return to the destroyed zone.

The article, Dans le camp de réfugiés palestiniens de Yarmouk, “Le régime voulait tuer les morts” (“In the Palestinian refugee camp of Yarmouk, ‘the regime wanted to kill the dead’”) was published in Libération on Tuesday, December 17.

In parallel to Myriam Boulos, who has also been reporting in Syria over the past fortnight, Özmen also documented the tragic search for loved ones unfolding at Sednaya Prison, one of the vast network of prisons established by Bashar al-Assad during his reign, where tens of thousands are estimated to have been tortured and killed.

Since December 8, people have been searching relentlessly for information about family members and loved ones who were seized by the regime over the past 13 years, many having disappeared without a trace.

Mathieu writes in detail of the scenes at Sednaya in the article “Sur les traces des disparus en Syrie ‘Tout ce que je sais, c’est qu’ils ont été détenus ici’” (“On the trail of the missing in Syria: ‘All I know is that they were detained here’”), published in Libération on Monday, December 16.

Özmen, who is from neighboring Turkey, has been documenting the Syrian Civil War and its ramifications since 2012, from the early days of the war to the fracturing of militias and militant groups, and the ensuing refugee crisis. He now remains on the ground to continue to document the beginnings of a new era for Syria.

Photographing Syria’s Civil War and its Ramifications

Damascus in the Days Following the Fall of Al-Assad