Three Voices From Palestine Curated by Myriam Boulos

A series of images by three local photographers in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank curated by Beirut-based Myriam Boulos. Warning: this article includes graphic content.

Samar Abu Elouf, Nidal Rohmi and Maen Hammad are grantees of the Arab Documentary Photography Program (ADPP), a joint initiative of the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture, the Magnum Foundation, and the Prince Claus Fund that provides support and mentorship to photographers from across the Arab region. All three are currently based in Palestine — Abu Elouf and Rohmi in the Gaza Strip, and Hammad in Ramallah, in the occupied West Bank.

The three photographers have each been producing work around life in occupied Palestinian territories for years. Abu Elouf has explored on the theme of light, or lack thereof in the Gaza Strip, with frequent power cuts and fuel shortages. Rohmi has worked on documenting the lives of people with amputated limbs due to Israeli airstrikes, whilst Hammad has focused on capturing the small, intimate Palestinian skateboarding scene as a form of escapism from frequent violence and tension brought about by the occupation.

Since Saturday, October 7, 2023, when Hamas launched an unprecedented attack against Israel, killing over a thousand and taking several hundred people as hostages, Israel has pounded the Gaza Strip with airstrikes, killing over 14,000 people at the time of writing, and displacing millions. Basic needs such as water and electricity have been blocked by the Israeli army, and almost no humanitarian aid has been able to enter the Strip. Meanwhile, Israeli forces and settlers have killed more Palestinians in the West Bank in the period since October 7 than in any other period over the past 15 years.

Abu Elouf and Rohmi are among the photographers and journalists who live and work in constant danger in Gaza, unable to leave. For other reporters, access to Palestinian territories — the Gaza Strip in particular — is extremely limited, and highly regulated by the Israeli army — if not entirely blocked.

Myriam Boulos, who is located in Beirut, Lebanon, has curated a selection of images from the three photographers since October 7.

Myriam Boulos: I have been denouncing the occupation of Palestine for a few years now. As an Arab woman, I always try to challenge the conventional ways of representing our region in photography. In a context where our history is controlled by politicians and the media, it is necessary to listen to Palestinian voices documenting from a local point of view.

Below is a selection of images from three photographers since October 7, 2023.

Samar Abu Elouf (@samarabuelouf)

MB: Samar, who is based in Gaza, has been reporting for the New York Times. In a video posted by the publication on October 22, Samar said: “I had to evacuate from Gaza City and head south on the Strip to Khan Younis city. There are constant strikes around me. There is horror, fear, anxiety. What I am seeing in the Khan Younis hospitals is no less than what I saw in Gaza City. The wounded and the people pulled out from underneath rubble are petrified and look like they’re lost. When I was filming in Gaza City, I would look through the children in fear that my children were among them. Now I live the same fear in Khan Younis.”

Samar’s project “The Light From Hell“, was previously published by the Arab Documentary Photography Program. The series explores the theme of light, and in her accompanying statement, she describes the power cuts, fuel shortages and lack of electricity that 2.5 million Palestinians must endure, a “war of darkness” that she longs to escape.

Maen Hammad (@maenster)

MB: Maen, who is currently based in the U.S., came to Palestine for what was meant to be seven days, then the war happened. Below is his statement:

“I am writing from the occupied West Bank, from the refugee camp preserving my father’s ancestry. I am writing with the pulse of freedom that my people embody, even when the world attempts to make it only a dream.

“As a photographer and documenter, I place my trust in my camera to convey this dream of ours, this craving for liberation. In a world where my people are maimed as dehumanized subjects or buried as numbers in a tally of deaths, I trust my camera to document the gravity of our life. To document our immortal confrontation against 75+ years of Israeli domination of our land, our bodies, and our collective imagination.

“I am writing from dignity. Documenting from proof. That this imagination of freedom is not out of reach. I am photographing with this freedom overflowing in my veins, from my people in Gaza, in the rolling hills of the West Bank, and the shores of historic Palestine. I am writing to you from Falasteen. From a free Palestine.”

October 5, 2023: “A small watermelon grows on a vine at my grandmother’s house in Helhul, situated in the southern region of the occupied West Bank. The image was captured two days before the outbreak of the war. My grandmother had used the skin and seeds of a previous watermelon as compost on her land months earlier. For decades, the watermelon has served as a symbol of Palestinian resilience. It first emerged after the Six-Day War in 1967, when Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza, including East Jerusalem. In response to the Israeli regime’s ban on public displays of the Palestinian flag, Palestinians began using the watermelon as an expression of their identity, as the fruit’s colors mirror those of the Palestinian flag.”

October 10, 2023: “Over 400 Gazans have found refuge at Ramallah’s Nadi Al-Sarryieh, typically a sports club but transformed into a shelter for Gaza’s day laborers who were working inside Israel when the war began. Some Gazans snuck into the occupied West Bank on their own, afraid of being attacked or arrested. Others were forcibly relocated by Israeli police who took them to multiple checkpoints scattered across the occupied West Bank.

“They were welcomed by Palestinian volunteers in Ramallah who tirelessly provide mattresses, food, medicine, a mobile salon — and unwavering solidarity. Thousands of other Gazan laborers have also sought refuge in various locations within the occupied West Bank. While lying on a cot, one man learned that three of his family members had been killed in an Israeli airstrike. He frantically asked his cousin in Gaza about the others, to which his cousin replied: ‘We are still sifting through the rubble.’”

October 14, 2023: “My uncle, diagnosed with prostate cancer, three weeks before the war began, is unable to receive medical treatment. The only PET scan available to determine the spread of cancer cells within his body is located in East Jerusalem, nine kilometers away. Thirteen minutes in the car, yet out of reach. On October 7, the Israeli occupation closed all checkpoints in the occupied West Bank. As his cancer cells continue to metastasize, my 73-year-old uncle, like countless others, remains glued to the TV, witnessing over 75 years of our people’s erasure. My uncle’s experience today offers a glimpse into what millions in Gaza have experienced for over 16 years: siege, collective punishment and domination.”

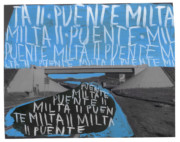

Maen’s project with the Arab Documentary Photography Program is titled “Landing” and explores the small, intimate skateboarding scene in Palestine — “this purposeful escape is a radical form of resistance to a headspace of violence,” he writes in the project statement. A sense of normality and community amidst the chaos.

Nidal Rohmi (@sameh_rahmi)

MB: Despite communication being incredibly difficult with our friends and colleagues in the Gaza Strip, Nidal Rohmi, who we know as Sameh, has been talking to Lebanese photographer Gabriel Ferneini on a daily basis. He told him: “Record everything because I might not be alive tomorrow and no one will know any of this. We have less than a 10% chance to survive because nowhere is safe.”

The images were taken between October 7 and October 10, before he decided to stop taking pictures in order to stay with his daughters and family.

Below is an extract of the conversations between Gabriel and Nidal Rohmi (Sameh) since early October.

October 9: Sameh calls me on Messenger. It’s the first time we have spoken since the war on Gaza started. He’s at his parents’ deserted house recharging his phone and laptop on their UPS battery because there’s no power in all of Gaza. His family is in Deir el Balah. It’s safer there. He has spent his day at the hospital documenting casualties. He’s saying they’ve never witnessed anything like this before. He tells me he hasn’t showered in 3 days. We promised each other we’d have a drink at Demo (our favorite bar in Beirut) when this is over.

October 11: Sameh sends a picture of his sister’s demolished house after a bombing. He left the area right before it happened. “Morale is high but it’s my daughters I’m worried about.”

October 13: Sameh made it to his daughters. He had been trying to reach them for days but couldn’t because of the unending airstrikes. A few hours later he sends a picture. He points out that he’s smiling “as promised.” Sameh mentions that he finally showered, that it’s worth more than “14 million dollars” precisely.

October 18: Sameh talks to me about Beirut, his eldest daughter. How she’s always afraid and follows him like his shadow. How she wants to sleep in his arms at night. His youngest, Fairuz, doesn’t believe him anymore when he tells her it’s fireworks they’re hearing outside. He tells me his feet can’t hold him.

October 19: We talk about the length of the internet cable they had to install from the closest house to them. We talk about the kids sleeping in the center of the room so they won’t be injured by shrapnel from the windows. We talk about how Sameh was able to get some gas. We talk about him walking all over the place to get water and food. He tells me “the narrative of the West is stronger than the narrative of an Arab.” Shortly after we hang up, he sends me a picture with his daughter and his nieces: “I was afraid to use my flash outside because of the planes flying above us.”

October 22: Today, Sameh mentions wanting to work again, that someone might lend him a helmet and flak jacket. I ask him to stay safe. He asks Beirut: “Will you let baba get back to work?” — “No” she says — “What’s more important, work or Beirut?” — “Beirut,” she says.

Rohmi has previously worked on a project named “My Phantom Walks With Me,” photographing people with amputated limbs due to Israeli airstrikes — of which there are thousands. He shares a little of his story through the project, how he was eight years old when his family moved back to Gaza in 1995, when “dreams were so high for liberation and for an independent state.” In 2001, he heard bombings for the first time, and since 2006, those bombings have not stopped.

Thank you to Myriam Boulos for her work in curating this selection of images and statements, and to Samar Abu Elouf, Nidal Rohmi and Maen Hammad for agreeing to share their stories.

Boulos also invites us to read Beyond Checkpoints on the Arab Documentary Photography Program website, a project by Samar Hazboun exploring a series of births that took place at checkpoints between the years 2000 and 2005.

Magnum Photos stands for the freedom of the press and against the targeting or silencing of journalists in the field.

From the Archive: Israel and Palestine

Peter van Agtmael: A Decade of Documenting Israel and Palestine