Inside Turkey’s Hidden War

Exploring the 'Kurdish question' and what it means for an already-unstable region

Magnum Photographers

For more than 30 years, the front pages of Turkey’s newspapers have seemed all too familiar to Emin Özmen: the coffins of Turkish soldiers covered with the red-and-white flag; headlines describing the Kurds as “despicable” and “traitors”; descriptions of “treacherous attacks in the southeast.” The Kurdish conflict has simmered for decades in Turkey — but two-and-a-half years ago, the insurgency entered one of its deadliest chapters.

Since the founding of the Turkish republic in 1923, the country’s Kurdish minority — an estimated 15.3 million people or around one-fifth of Turkey’s population — has faced repression, often restricted from expressing their culture or even speaking the Kurdish language. The Kurds, sometimes described as the world’s largest ethnic group without a state, number roughly 30 million people across Iraq, Iran, Turkey and Syria — an ever-changing regional backdrop against the national aspiration of the Kurds. Within Turkey, the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK), designated a terrorist organization by the U.S., NATO and the EU, has been waging a guerrilla campaign against the Turkish government since 1984 to secure political rights and self-determination for Kurds — and to establish an independent Kurdish state. The insurgency has led to some 40,000 deaths in Turkey.

" Without evidence, there is no war."

- Emin Özmen

Both Özmen and Moises Saman have a personal connection to this deeply complex subject. Özmen is Turkish by birth and “grew up in a culture where the Kurdish issue is ever-present.” Since 2014, he has dedicated a great deal of his work to the Kurdish community, particularly in the largely Kurdish southeast part of Turkey. The deterioration of Turkey’s free press means that the official state view dominates public opinion. “The media tend to show the conflict in a very Manichean way,” Özmen says. “But I’ve rarely seen a conflict where everything was black or white. I wanted to go there and document what was really going on.”

Saman’s work on the transnational Kurdish conflict, meanwhile, arose out of his extensive work on the Arab Spring. “The Kurds emerged from this post-Arab Spring period as the most consequential non-state actors in the Middle East, so it was a very natural continuation of my ongoing body of work on this region,” he says, noting that he visited southeast Turkey three times between 2014 and 2016. But the issue also had a personal dimension: while living in Cairo in 2011, Saman fell in love with an Iraqi-Kurdish woman whom he married in 2016. “I wanted to know more about the land and the people where she came from,” he says.

With conflict inflaming Syria and Iraq in recent years, the Kurds have become one of many local groups competing for control of territory and power. In Syria, the Kurdish minority in the north essentially seceded in 2012 — becoming America’s ally in fighting ISIS in Syria. (The U.S. has provided the Syrian Kurds with arms, training and logistical support, despite their connections to the terrorist-designated PKK.) During the battle for the Syrian border city of Kobani in fall 2014 to spring 2015, Kurdish militants won the world’s admiration and garnered attention for their cause.

Ankara meanwhile has remained deeply suspicious of the Syrian Kurds fighting ISIS, fearing the potential creation of a powerful — and now well-armed — Kurdish fighting force that would straddle the Turkish-Syrian border and challenge Turkey’s authority. The breakdown in government in Iraq has also strengthened nationalist sentiment among Kurdish groups there, who have since become bolder in pursuing their national ambitions. Iraqi Kurds voted overwhelmingly for independence in late September, but the Iraqi government responded with force, seizing one-fifth of Kurdish-controlled territory.

But the story of Turkey vs. the Kurds is more complex than a clash between state and society — and the stance of its current leader reflects that. During his tenure as prime minister from 2003 to 2014, Erdogan was seen by many Kurds as pro-Kurdish rights — even using the word ‘Kurdistan.’ He supported the ‘Kurdish opening’ reforms that began in 2009 and brandished a copy of the Kurdish-language Quran at an election rally in Turkey’s mainly Kurdish southeast in May 2015. In 2012, with the war at a stalemate, Turkey and the PKK began negotiations and declared a ceasefire in March 2013 — though scattered violence continued. “I remember that it was a huge relief when the peace process started,” says Özmen. “We all hoped for peace and a real solution that would put an end to this bloody conflict that has plagued Turkey for so long.”

It was not to be. The conflict in Syria complicated matters, as did internal politics in Turkey. After becoming president in 2014, Erdogan launched a bid for an executive presidency — strongly opposed by the pro-Kurdish HDP, which managed to galvanize support not only from the Kurds but also from Turkey’s liberal voters. In 2015, the HDP managed to triple its seats, meaning that Erdogan’s party lost its parliamentary majority for the first time since coming to power 13 years earlier.

After an ISIS attack killed 30 Kurds at a peaceful rally, the PKK responded by assassinating two police officers, blaming Ankara for failing to protect Kurdish citizens. The ceasefire collapsed in July 2015 and Erdogan began collaborating with Turkish nationalists to keep the Kurds out of power, calling a snap election in November 2015.

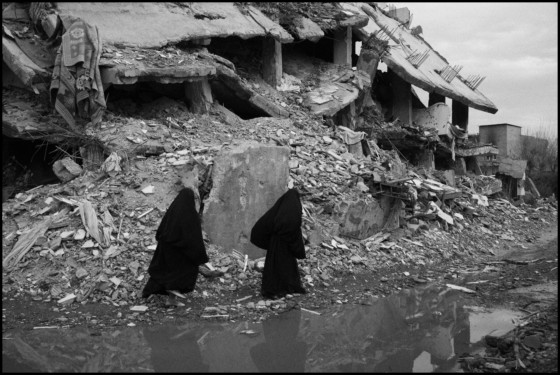

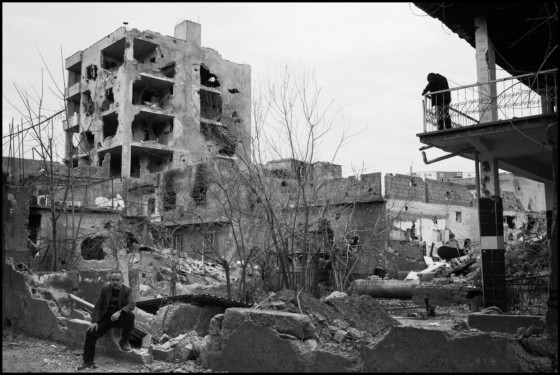

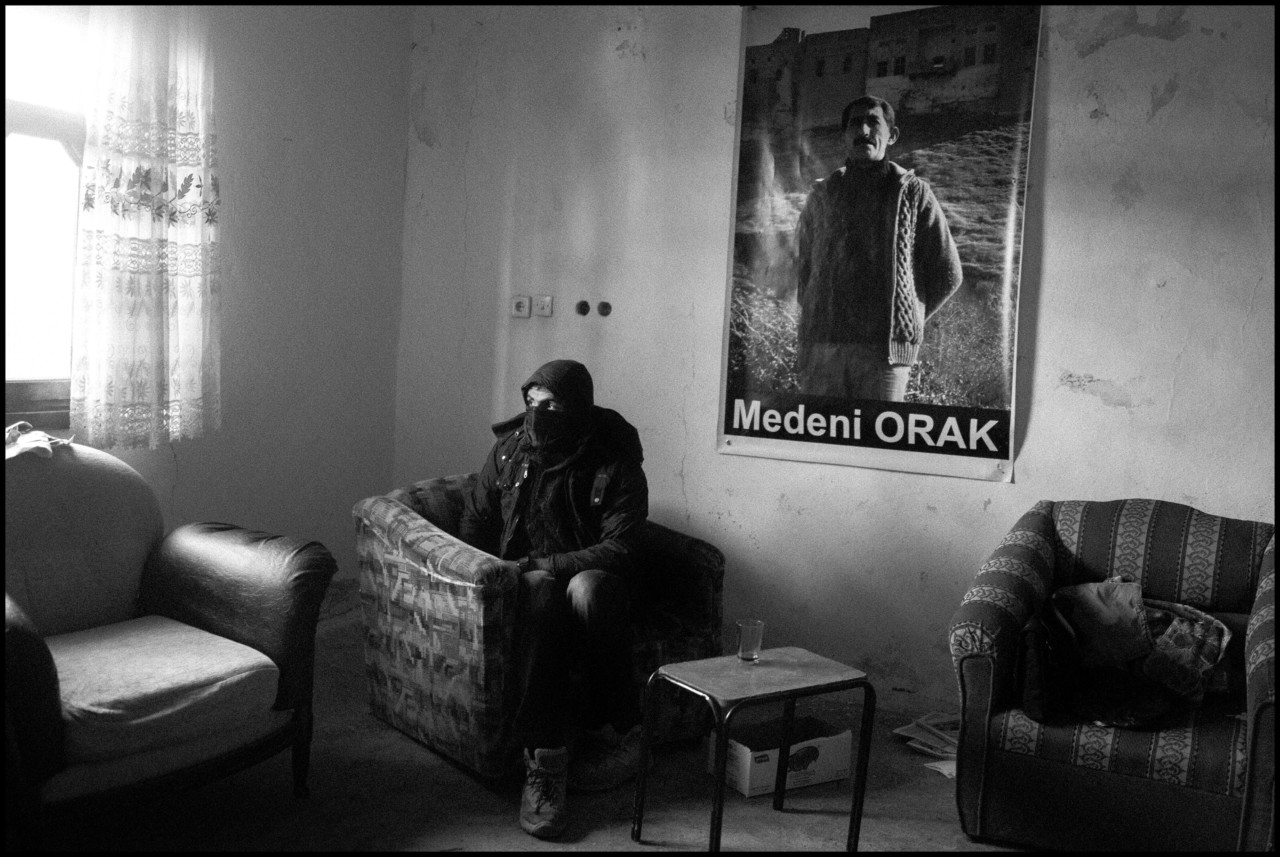

Unprecedented violence immediately took the place of the ceasefire but this time, the battle moved to the cities. Unlike the traditional rural-style guerrilla warfare, young Kurdish militants seized control of urban centers across the southeast, clashing with the Turkish military. The army placed entire towns under 24-hour curfews, shelling residential areas, destroying thousands of buildings. More than 350,000 people fled their homes and, according to the International Crisis Group more than 3,000 people have died in the clashes, including at least 437 civilians. Nearly 40 percent of deaths since July 2015 have been in urban areas.

"They are all lost in a spirit of revenge"

- Emin Özmen

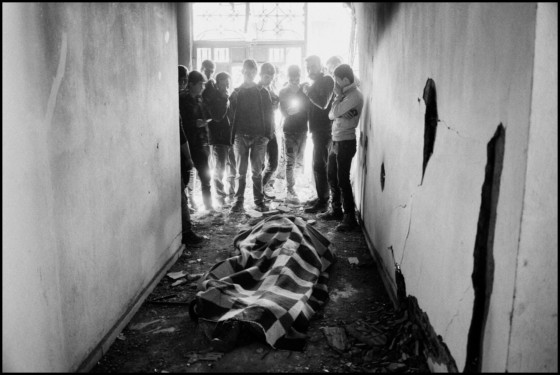

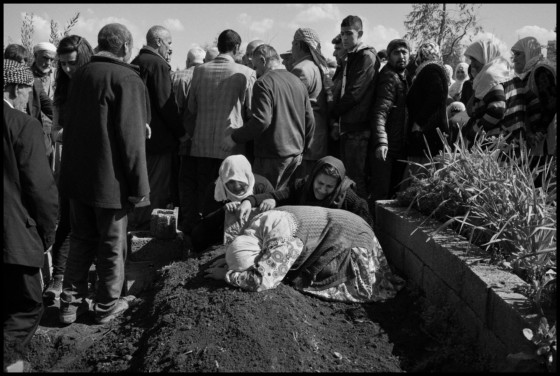

Saman photographed funerals taking place in Cizre, one of the main cities in the southeast, in the immediate aftermath of the Turkish army’s siege of the city. “Bodies were still being found in the rubble of bombed out buildings and there was an utter sense of shock at the extent of the destruction.”

Both Özmen and Saman describe the difficulties when it comes to photographing in this area. “When you enter these areas, it is full of checkpoints and you are under high security control from Turkish soldiers and police officers. They check your background, your previous reports and even your social media accounts,” says Özmen.

Saman adds: “Even with foreign journalist accreditation from the Turkish government, it was very difficult to report from the southeast and it has gotten even harder. As a journalist, you run the risk of being arrested at any moment.” Even once through the checkpoints, it’s difficult to gain the trust of the Kurdish people in the area, “the real downtrodden witnesses of this conflict,” as Özmen calls them. They wonder whether the journalists are undercover secret service members, and question why they care.

"Fighting for their cause gave them a purpose and a sense of belonging that was bigger than anything they had ever known"

- Moises Saman

In the last few years, Kurdish armed groups have repeatedly attacked Ankara and Istanbul. In October 2015, an offshoot of the PKK claimed an attack at a peace rally in Ankara that killed more than 100 people; multiple attacks in 2016 were claimed by Kurdish militants, killing dozens. Political repression of the Kurds also accelerated after the attempted coup in July 2016. Thousands of Kurdish politicians, academics and civilians have faced charges of terrorism and been imprisoned.

The recent wave of violence has spawned a new generation of Kurdish fighters. Saman and Özmen say as in many other conflicts around the world, most Kurdish fighters were young — often under the age of 20 — and from poor families. “In the case of the female fighters, some spoke about joining the guerrilla as a way out of abusive family relationships,” says Saman. From speaking to the young men and women, he realized there were a lot of conflicting emotions but “the lasting impression was that fighting for their cause gave them a purpose and a sense of belonging that was bigger than anything they had ever known.”

Özmen, on the other hand, says some of those he met didn’t even know why they were fighting anymore. Almost all the fighters he met had lost at least one relative during the conflict. “They are all lost in a spirit of revenge.” Özmen worries about the long-term polarization of the country along ethnic fault lines, as children and teenagers in southeastern Turkey feel more and more disconnected from Turkey — making a peace process increasingly unlikely. He fears seeing “the radicalization of the young people in this region — a new generation of Kurds, traumatized, growing with anger. What will be the consequences in a few years?”

While the international community has not necessarily ignored the Kurdish conflict, the fact that it remains frozen after decades means it garners relatively few headlines. Since the Kurdish issue involves so many countries and is linked to the regional politics playing out in Syria, Iraq and Iran, it seems particularly difficult to resolve or predict what will happen. “These last decades have shown that the conflict could ignite, then calm down, and resume again,” says Özmen. “The slightest intervention can ignite an entire region.”

Both photographers feel a responsibility to document this issue, as well as a personal connection to what happens in this part of the world. But Özmen says while he hopes to generate a response from the public, what he has witnessed in the last few years has not given him much hope. The “hidden war” has been going on for years. “But without evidence, there is no war,” he says. “That’s why it’s important for me to document it with my photos.”