USAID: The Human Cost of Trump’s Cuts

Countries worldwide are feeling the impact of the Trump administration’s recent cuts to foreign aid, which have amounted to about $60 billion dollars

On January 20, President Trump signed an executive order to freeze U.S. foreign aid, pending a review of 90 days. After only a few weeks, under the notion that “the United States foreign aid industry and bureaucracy are not aligned with American interests and in many cases antithetical to American values,” the federal government dismantled the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). At least 83% of the USAID grants have been eliminated thus far, nearly $60 billion dollars of the budget has been seized, and thousands of workers have been furloughed or fired. The drastic slash has put life-saving services and medication for millions at a standstill, while the future of the agency remains uncertain.

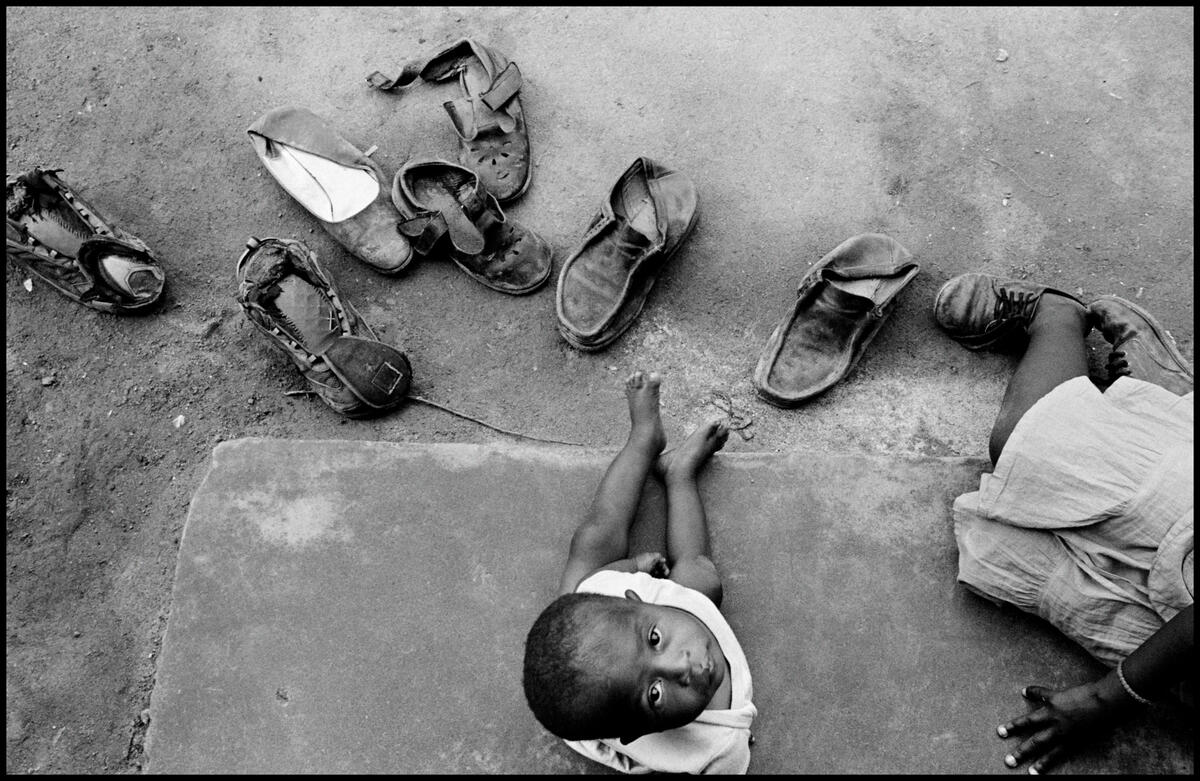

Magnum photographers have traveled to many of the countries benefiting from or relying on foreign aid programs, relaying stories of people around the world given access to essential services financed by the U.S. government. Their images are testimonies not only to the individuals receiving aid and their battles with health crises, but the resilience of their families, the tireless efforts of aid staff, the humanist initiative to save countless lives, and the basic right to healthcare.

Formed under John F. Kennedy in 1961, USAID has undertaken humanitarian and development projects in more than 120 countries, with the goal of tackling disease prevention, reducing poverty, and providing emergency relief worldwide.

After being placed on leave, Nicholas Enrich, an assistant administrator for global health at USAID, released memos published by The New York Times estimating the devastating effects of slashing foreign aid programs: “up to 18 million additional cases of malaria per year and potentially 166,000 additional deaths; 200,000 children paralyzed with polio annually with millions of more infections; one million children not treated for severe acute malnutrition each year; uncontrolled outbreaks of mpox and bird flu, including as many as 105 million cases in the United States alone; rising maternal and children’s mortality in 48 countries”, among other daunting repercussions.

The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)

In 2009, eight Magnum photographers — Jonas Bendiksen, Jim Goldberg, Alex Majoli, Steve McCurry, Paolo Pellegrin, Gilles Peress, Eli Reed, and Larry Towell — partnered with The Global Fund on a large-scale project to document the experiences of people living with HIV and AIDS, and the transformative effects of antiretroviral therapy on their lives. The result was Access to Life, an exhibition and book presenting parallel visual narratives of people battling the disease in already precarious contexts.

Now, in the wake of Trump’s freeze, AIDS programs such as the PEPFAR are in limbo, as they heavily rely on USAID. People like Kumar in Goldberg’s series, which features portraits of HIV patients overlaid with written testimonies, are struggling to receive life-changing therapy. Although limited waivers have allowed some PEPFAR programs to resume, many are immobilized.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)

More recently, in 2023, Moises Saman was on the ground in Libya in the wake of the fatal floods that ripped across the northeastern coast. After two dams collapsed, flood water swept through the city of Derna, leaving more than 4,000 people dead, 10,000 missing, and tens of thousands displaced. Saman’s images communicate the devastating aftermath as well as the rescue crews’ emergency response efforts. Many of the injured were taken to hospitals supported by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), a sexual and reproductive health agency.

Due to the Trump administration’s cuts, the agency saw the termination of 48 grants, totaling approximately $377 million, which provided “critical maternal health care, protection from violence, rape treatment and other vital services in over 25 crisis-stricken countries and territories,” according to the UNFPA. While the U.S. government has since reinstated seven programs, the other 41 projects have been dissolved.

In 2022, Sabiha Çimen traveled to Zanzibar, where the UNFPA trains midwives and birth attendants to manage complications during childbirth and reduce maternal mortality, activities which are now in jeopardy without U.S. funding.

Çimen photographed the desperate conditions in a hospital where two or three mothers are forced to share a single bed with their newborn babies. The photographer spoke to midwife Sanura Abdulla Salim, who explains: “We have very busy days here in hospital and low capacity to welcome the flux, an average of three women sharing one bed. Three nurses working for forty mothers. We need quality care, and better standards.”

"We need quality care, and better standards."

-

Nanna Heitmann’s photographs tell the story of the Life Skills Education (LSE) initiative in India, which is also backed by the UNFPA. The initiative aims to empower young people with essential life skills to make informed choices about their health and well-being, while addressing social injustices such as gender inequality and child marriage.

Divya Chaudhry was 16 when Heitmann photographed her in 2022, living in the Tikuri district of Madhya Pradesh, the state with the fifth largest population in India. The region’s rich cultural heritage and vibrant wildlife is affected by drought, economic crisis, malnutrition, hunger, and high infant and child mortality rates. Despite these conditions, and thanks to Divya’s supportive parents and the LSE initiative, Divya and her sister could prioritize education and independence.

“They wanted to invest all their resources into their daughters,” Heitmann recounts, “because unlike the popular narrative in their region, they did not consider their daughters a burden, but young girls who had untapped and unlimited potential.” Their mother, Miradevi Ahirwal, is an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) supervisor who helps serve a total of 10,000 families in the region, giving women access to contraceptive methods and family planning programs.

Heitmann quotes Divya as saying: “I have chosen the science field because just like my mother, I want to work for women’s health. What particularly piqued my interest was the RKSK (Youth and Adolescent Health programme in India) workshop that took place in my school. I was able to participate actively, and soon I was shortlisted to represent my district in the monthly meetings to further educate young people on their health concerns and issues.” The Trump administration’s cuts will impact these resources designed for young women to thrive.

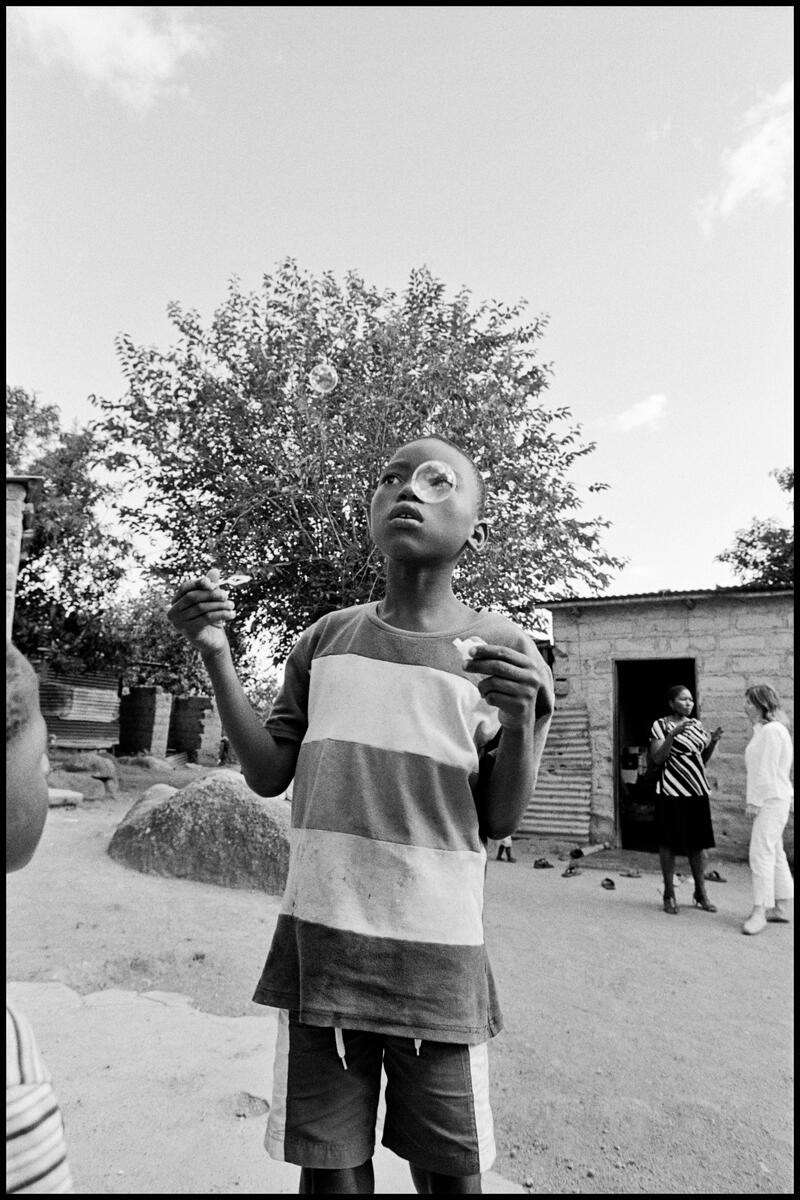

On assignment with the UNFPA, also in 2022, Lindokuhle Sobekwa traveled to Nigeria to document the work of the Young Mums’ Clinic, which offers support for young pregnant women in a country where teenage pregnancy rates are high.

In the state of Lagos, Sobekwa closely captured the everyday life of Kehinde, then 19 years old, who got pregnant in 2020 after being sexually abused. Kehinde significantly benefited from the UNFPA-backed clinic, which provided free antenatal care services, free baby care items, psychological support and family planning counseling. In conversation with Sobekwa, Kehinde affirmed, “I got my confidence back by accessing the YMC.”

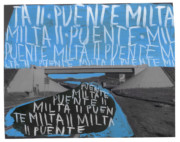

Also on assignment for the UNFPA, Newsha Tavakolian documented humanitarian work in the remote northern region of Roraima in Brazil, where information about contraception is often limited. There, Tavakolian discovered the Pintolândia shelter, which houses members of the Warao tribe who fled their homes in Venezuela. Tavakolian writes that refugees “rush toward the Brazilian border to get away from the dire social, political, and economic conditions of their homeland. Their main priority is finding enough food to sustain themselves on a day-to-day basis, since the food crisis in Venezuela has made life extremely difficult for them.”

In Bôca da Mata, Tavakolian met Dr. Pamela Biasdakosta, who works with a majority population of indigenous people. “Indigenous tribes in Brazil often do not have access to standard healthcare, which leads to problematic pregnancies and births, and of course various birth defects in babies,” Tavakolian recounts from their conversation. Thanks to local clinics, women are improving their chances of healthier pregnancies and babies. Yet, without U.S. funding, the efforts to raise awareness among women about their sexual health and reproductive rights are now at risk.

Magnum photographers continue to document humanitarian efforts that shape the futures of communities in dire need of support. Currently on exhibition at Foam in Amsterdam, Sakir Khader’s photographs of the violence against Palestinians in the West Bank point to the issue of global aid to Gaza, which, already subject to months of blockades by the Israeli government, are further disrupted by the Trump administration’s cuts. These collective visual narratives remind us that behind thousands of aid infrastructures are individuals and their families who depend on life-saving programs.

View a larger selection of work by Magnum photographers documenting global humanitarian aid here.