100 Years of Werner Bischof

To mark the centenary of Werner Bischof's birth, Magnum's photographers respond to his legacy in images and words

Magnum Photographers

An intrepid adventurer, Swiss photographer and Magnum member Werner Bischof was personally committed to report on injustice. His photojournalism was published in the most well-read magazines, such as Life and the Picture Post; he was destined to be one of the great photographers of his age, with a diverse and wide-ranging practice that also included pioneering darkroom techniques, experiments with abstraction, and fashion. A car accident in the Andes led to his premature death in 1954, but his legacy has inspired generations of photographers.

2016 marks the centenary of Bischof’s birth, and to mark the occasion, international exhibitions and several books were launched celebrating his work (as well as a special collection of prints, contact sheets and posters). In homage to Bischof, Magnum’s photographers selected the images from his archive that mean the most to them, and responded to them through their own words and pictures. Together, these images and texts connect the various styles of the agency’s photographers, highlighting the invisible threads that bind the practices within Magnum, and revealing the symbols and images that echo each other through the ages.

Martin Parr comments on Bischof’s Courtyard of the Meiji Shrine (above), and responds to it with an image from his early black and white work (below): “One of the most iconic Bischof images is his Japanese image of the walkers, with umbrellas in the snow. It’s one of those images that enters our subconscious and just stays there. Here is a response to this from an early project, called Bad Weather, where I explored this national obsession in Britain, and only shot images in the rain and snow. Part of the time I was shooting this, I lived in Ireland and extended it to cover here too. This is the most famous bridge in Dublin, the Halfpenny Bridge, bang in the center of the city.”

"Only work done in depth, with total commitment, and fought for with the whole heart, can have any value"

- Werner Bischof

Parr wasn’t the only photographer inspired by this image. “In 2000, at the Meiji shrine, which was photographed by Werner in 1951, I looked for the spot where his photo was taken. But fifty years is a long time and the shrine had changed. Besides, there was no snow! There was no snow either at the Oyashimo shrine, which I visited later in Ise, dedicated to the kami (the spirit) of love and family. Pigeons are roaming spirits, revered by visitors and fed by the High Priest. I asked the kami of snow to bring some snow as I wished to photograph the roof-wings of the temple in white. On the third night, the kami of snow obliged by offering flakes which are immediately dispersed by the wind. Is the kami of wind angry with me for not having honoured him properly as I did his colleague of snow? Or is the kami of wind making sure, by blowing, that the snow will not melt until the morning, when I can photograph the temple under a blanket of white?”– Abbas

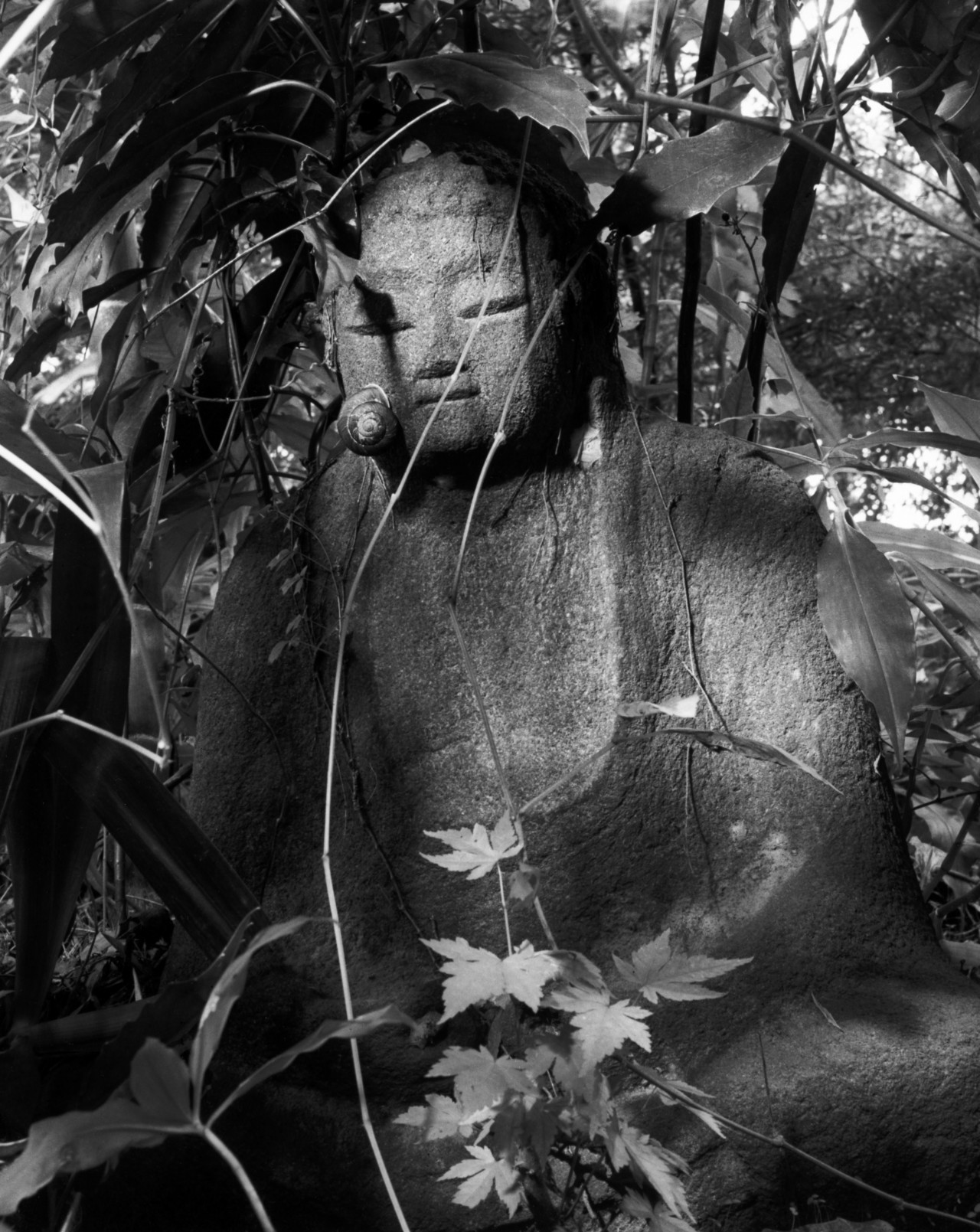

“When I look through Werner’s work I see so many parallels, so many places where our paths have crossed: from Machu Picchu to Japan, from a love of nature and form, to a warmhearted approach to the human condition. Ultimately, I wanted to choose a picture, or pictures, that underline Werner’s deep sense of the connection between nature and society. I am sure that, had Werner been alive today, he would have embraced environmentalism, even deep ecology. I see him walking through woods like the path through Nugent’s wood here.”– Stuart Franklin

Chris Anderson remembers his early days as a Magnum photographer and finding Bischof’s original contact sheets in the archive. “When I first entered Magnum, I would go to the New York office and spend hours looking through the files of contact sheets. The captions were sometimes handwritten or hammered out on type writers. The very first file I remember opening was Bischof’s trip to Japan in the 40s or 50s. Seeing all the images of the contact sheets felt like being transported through time and being on the journey with him. It was the beginning of feeling connected to the history of Magnum in a very visceral and powerful way. As a young photographer trying to find my place in this family, it sort of felt like Werner was welcoming me and showing me the way.” – Christopher Anderson

Some found it hard to limit their choices to a single image; above, we show one of Constantine Manos’s choices, he explains: “Werner Bischof was a photographer whose pictures imparted elegance and poetry to the most ordinary of human situations. His death at the age of thirty-eight was a shock to the Magnum family. It is a tribute to his talent that within such a short life he left behind such a large and beautiful body of work, from which I have chosen six of my favorite images.” – Constantine Manos

Marco Bischof was a very young child when his father, Werner, died. Today, he is the custodian of his legacy and manages his estate. He played a crucial role in this year’s programme of books and exhibitions. Alec Soth finds this relationship deeply moving.

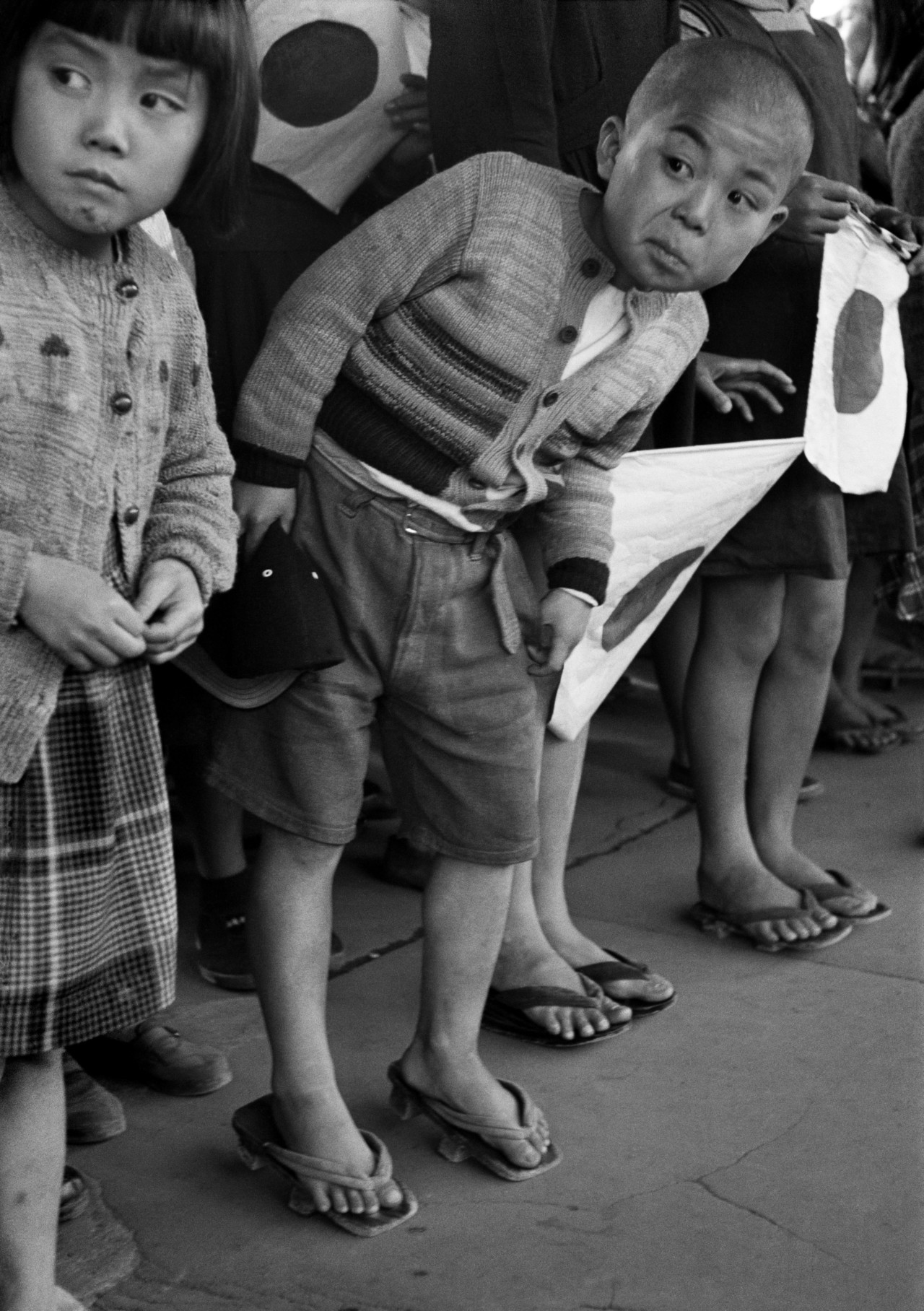

“‘Children are surely a paradise in Japan, so sanguine, so unpolitical, so untainted, seeing everything with wide eyes, the mother drags them unremittingly down the street, while they stop for a moment and look at something they’ve seen, something that urgently commands their attention. It is the same the world over, wherever children are to be found, and now I know you feel the same joy, because you understand and allow our little boy time to loiter, letting him zig-zag his way along the street.’

“Werner Bischof wrote this letter to his wife Roselina in 1951. A few years later he was dead. His son Marco came to learn about his father through his letters and photographs. Like many others, I’ve come to know Werner Bischof through his son’s eyes. Consequently, when I think of Werner Bischof’s work, I think first of this connection between father and son. Though I’ve never seen a picture of Marco taken by Werner, I see Marco’s spirit in all of the photographs he made of children.”– Alec Soth

Werner Bischof and Chris Steele-Perkins share a passion for Japan, which moved Steele-Perkins to write:

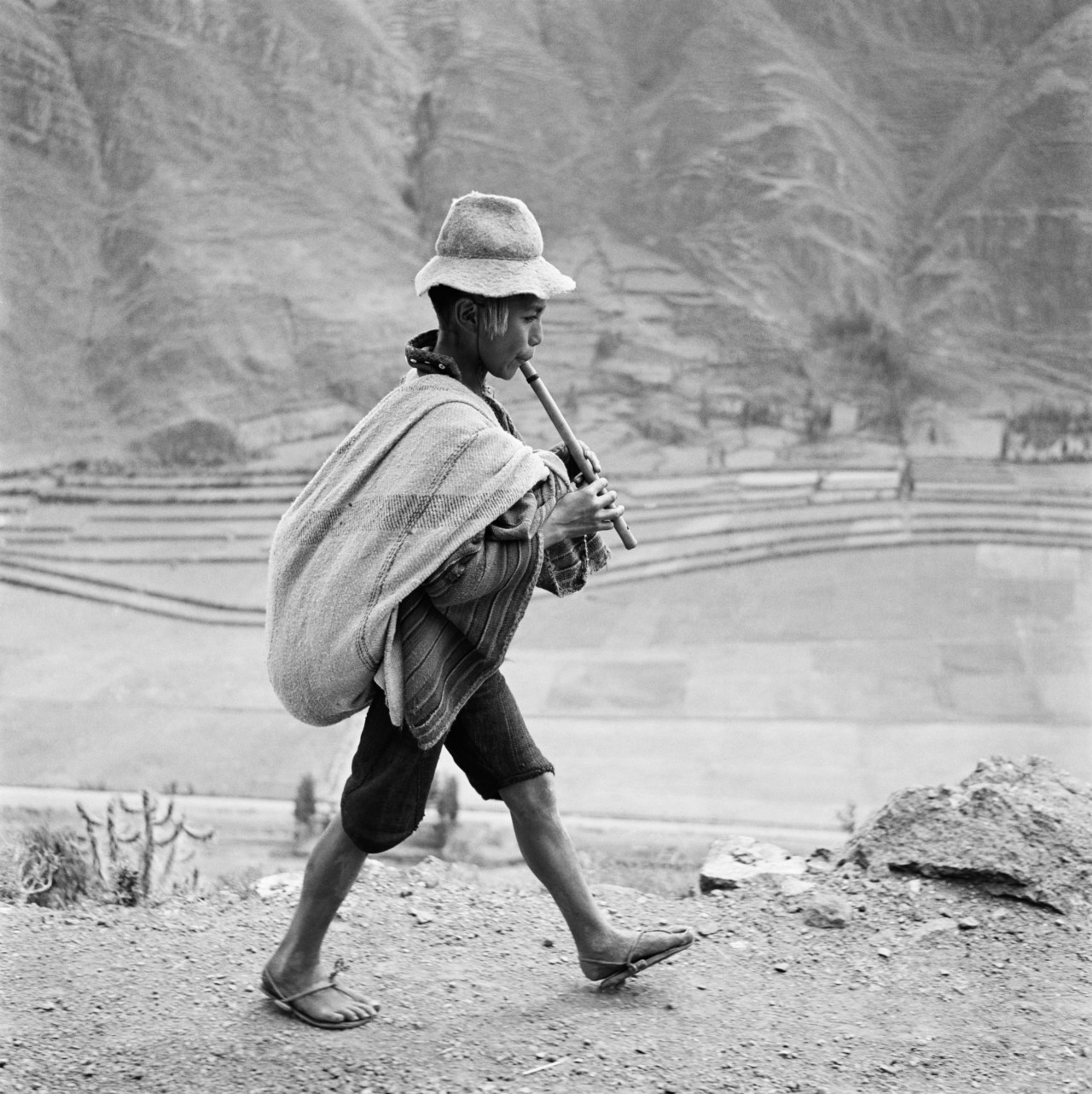

“Werner Bischof’s work is nearly always described as ‘humanitarian’ and as being informed with ’empathy’, and for good reason. I only know the man through his photographs and some of his writing, and it seems to me he was someone who liked people and was happy to celebrate them, and nowhere is that clearer than in his photographs of children. Probably his most famous image, of a boy playing a flute on the road in Peru, is infused with that sense of a child wrapped up in his inner world, of his childhood not yet lost and its music echoing through the valley.

On the anniversary of Werner Bischof’s birth I have chosen this image of his to respond to because, for different reasons, Werner and I both developed a serious relationship with Japan and its people and have tried to express some of it through photography. In his photograph the two children are wrapped, in their own ways, in the moment. The girl perhaps a little apprehensive as she knits her fingers, after all it is the Emperor they are waiting for, and the boy, excited, even impatient. Behind them others hold flags. The children are not interested in Werner, but Werner is interested in them, and he cares about how they are feeling and because of that he can still communicate that feeling to his audience, to us, more than 60 years later. That is one of the qualities that made him a great photographer.” – Chris Steele-Perkins

Creating connections between post-war Europe and the current conflict in Syria, Lorenzo Meloni writes of his image choices:

“Bischof’s images of the aftermath of the Second World War have longevity. This 1946 picture of an Italian woman clearing rubble in the town of Montecassino is an image relevant to any war, where women are so often left to pick up the pieces after the fighting has stopped. Almost 70 years later, similar scenes are unfolding across countries affected by 21st-century conflicts, such as Syria. In my 2015 image of a woman surveying the rubble of her former home in the town of Kobane, I found a visual connection with Bischof’s image, where the Syria of today and the Italy of 70 years ago could be almost interchangeable. That Bischof was a similar age to me when he took this picture gives the two images a stronger connection, and also highlights the legacy of Magnum photographers, who continue to document the many realities of the aftermath of wars.”– Lorenzo Meloni

Matt Black’s homage to Bischof celebrates the humanity that motivated his work: “Long before I became a Magnum nominee, I admired Werner Bischof for his commitment to everyday life in the face of war, poverty, and remoteness. His decision to not be swayed by the headlines, his dedication to being an author, and his commitment to marginalized people in forgotten places has been an inspiration. This image, of a reindeer roundup in Finland in 1948, reflects what I admire most about Bischof’s photography: he captures the energy, difficulty, and grace of lives eked out in the margins; pays homage to labor being honestly performed; acknowledges the coexistence of beauty and hardship; and attests to the fact that seemingly small moments in small places can reflect our biggest truths. In this image, Bischof points us towards this high potential and deep calling.” – Matt Black

"The image reminds me of Werner's iconic flutist and I would like to add it to the Magnum collective memory"

- Micha Bar-Am

Many were moved by Bischof’s iconic image of the flute-player. “I was thinking of Werner Bischof during my first trip outside Europe. The work of Werner Bischof was part of my education at the Royal Academy in Gent, so the image was familiar when I first traveled to India. At the time there were not so many photo magazines available in Belgium, the one that I bought regularly was the French Photo where I saw that image again before I joined Magnum. Images, paintings and movies are constantly in my head and it does happen from time to time that I recognise, very often unconsciously, certain remakes of these pieces of art in real life. In this case the similarity was too obvious, so I decided not to use the image I took myself. It’s not that great anyway.”– Carl De Keyzer

“The more you settle down with your own photography, and your own strategy in this visual act, the more it is difficult for you to determine and establish the contribution of other photographers to your composition, style and attractions. For almost fifty years, I had many click moments in my life and slowly my eyes moved towards random and ad-libbed forms. The centenary of the birth of Werner Bischof rekindles and brightens up the meaning of his important contribution to the history of photography and brings him back again to our present. Talking about him with my partner, Sergine, also a photographer, she immediately reminded me of a picture taken in 1969 but printed later in 2006. I told her what pleasure it gave me to find out about this forgotten picture in my contact sheets. It was a picture from my first trip to Sub-Saharan Africa, the last take, the 36A, from the first film roll of this first day of photo-reportage, on August 6, 1969. It was with a lot of apprehension that I placed in my viewfinder these three little children passing through the village in an absolute quietness. I remember perfectly well this moment: my emotional state and my anxiety.

I hoped this picture would have pleased Werner, with its Bischofian atmosphere, and that he would allow me to make a link between my picture and his famous Peruvian flutist. Werner knew how to give balance and strength to simplicity, which he regarded as very beautiful. He did not yield to the temptation of the effect, but preferred instead to give the biggest space possible to the subject of his picture. Maybe, there is, in my picture of these Chadian children, some of the subtle delicateness and aesthetic simplicity of Werner Bischof. If this is the case, I would be very proud. This is my little tribute to Werner. I hope I have been worthy of him.”– Guy Le Querrec

“I would like to contribute to Werner’s centenary an image which was made at about the same time Werner lost his life in the Andes: I was trekking in the Biblical Galilee landscapes when I met this young shepherd. The image reminds me of Werner’s iconic flutist and I would like to add it to the Magnum collective memory.”– Micha Bar-Am

“Most of us never met Werner Bischof, nevertheless we are deeply in his debt. His body of work combines sensitivity and elegance, honesty and a hope for redemption. His love and respect for fellow human beings and their ways of life is impossible to overlook. He said it best himself, ‘Only work done in depth, with total commitment, and fought for with the whole heart, can have any value.'”– Steve McCurry

Finally, Carolyn Drake reminds us of the modernity of Bischof’s work, and how it still resonates today: “I had to pause at this 1952 image of North Korean POWs dancing in masks in front of a statue of liberty replica on Koje Do Island. The symbols feel familiar, yet their meaning is unclear. Since the caption didn’t answer my questions, I looked online. Clicking from link to link, I found answers, and then answers that contradicted those answers. What I was left with was a reminder that history and truth are themselves a battleground. Traditional war narratives normally include a hero and an enemy. But who is who in this scene? I’m not at all sure. When I look at this image, I feel like I’m seeing something I’m not supposed to, a secret only partially, inadvertently exposed. Despite being 60 years old, this image remains a very contemporary depiction of war.” – Carolyn Drake