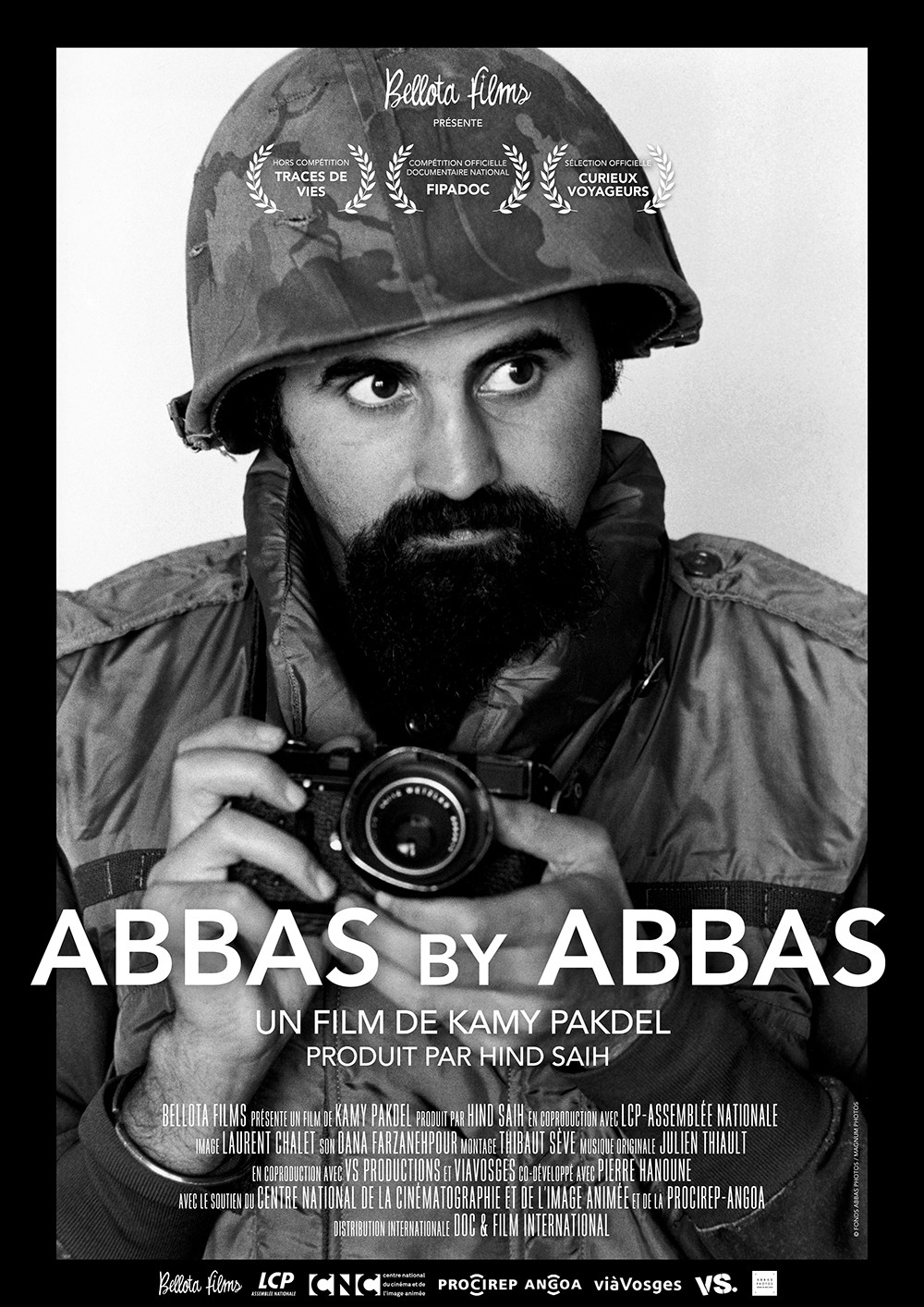

Abbas by Abbas

Filmmaker Kamy Pakdel reveals the story behind a new documentary on Magnum photographer Abbas, completed mere days before his death

A soon to be released documentary sees the late Franco-Iranian photographer Abbas discussing his work, on camera for the first time, over ten days in the Magnum Photos office in Paris. Below, the film’s director Kamy Pakdel discusses how the project came about, and how its making unfolded over the last weeks of Abbas’ life.

‘Abbas by Abbas’ will be premiered on Tuesday, February 18 at 8.30pm on the LCP Assemblée Nationale channel in France. You can see the official trailer below, and learn more about the film here.

The Iranian photographer Abbas Attar – better known by his mononym Abbas – was a man of many sides. “What was fascinating about Abbas was that he was very tough and rough but, at the same time, very sweet and kind, and extremely fair. I found this mixture really unusual,” says Kamy Pakdel, the director of a new documentary about the Iranian image-maker, titled Abbas by Abbas.

This combination, Pakdel notes, speaking from his home in Paris, is something that emanates from Abbas’ photographs, which frequently depict war, revolution and religious fanaticism, but in a poetic, very human, manner. “His behavior and character were really reflected in his pictures.”

Pakdel should know: an art director in publishing by profession, he worked with Abbas to realize some of the photographer’s best-known books, beginning with his famous 2002 publication, Iran Diary 1971-2002, documenting Abbas’ native country before, during and after the revolution. It was while making Iran Diary – during which time Abbas regaled him with endless fascinating stories that couldn’t possibly be squeezed into a book – that Pakdel suggested making a documentary together. “Abbas didn’t take it seriously,” he recalls. “He said that this type of film, like making a monograph, was something one did just before you die.”

Pakdel repeated his request countless times over the next decade, and always got the same answer: “not yet.” Fast forward another ten years, however, and Pakdel, who had remained close with the photographer, heard that Abbas was unwell and had begun work on his monograph. The pair arranged to meet at Abbas’ Paris apartment. Pakdel, who hadn’t seen the 74-year-old photographer for nine months, was shocked by his appearance: “he had aged ten years in that time.” Pakdel asked Abbas whether he thought it might now be time to make the film, the photographer replied that he had never ruled it out, adding, “if you still want to do it you have very little time left…”

Pakdel assembled his team in just ten days, persuading Oscar-winning director of photography, Laurent Chalet, and sound designer, Dana Farzanehpour, to come on board – after seeking Abbas’ approval. “I really wanted him to feel in control of the film, because he was a man of control,” he explains.

That said, Pakdel had a very specific kind of film in mind, and it didn’t entirely align with Abbas’ own ideas. “Initially, Abbas wanted to tell me his entire story, from beginning to end. I told him we didn’t have time for that, that it would be boring,” he chuckles. “I pointed out that in his books, he always talked about the factual elements of his work – everything but himself, his emotions, what he went through.” Immediately he said, ‘That’s not interesting, no one cares.’ So I knew it was going to be tough.”

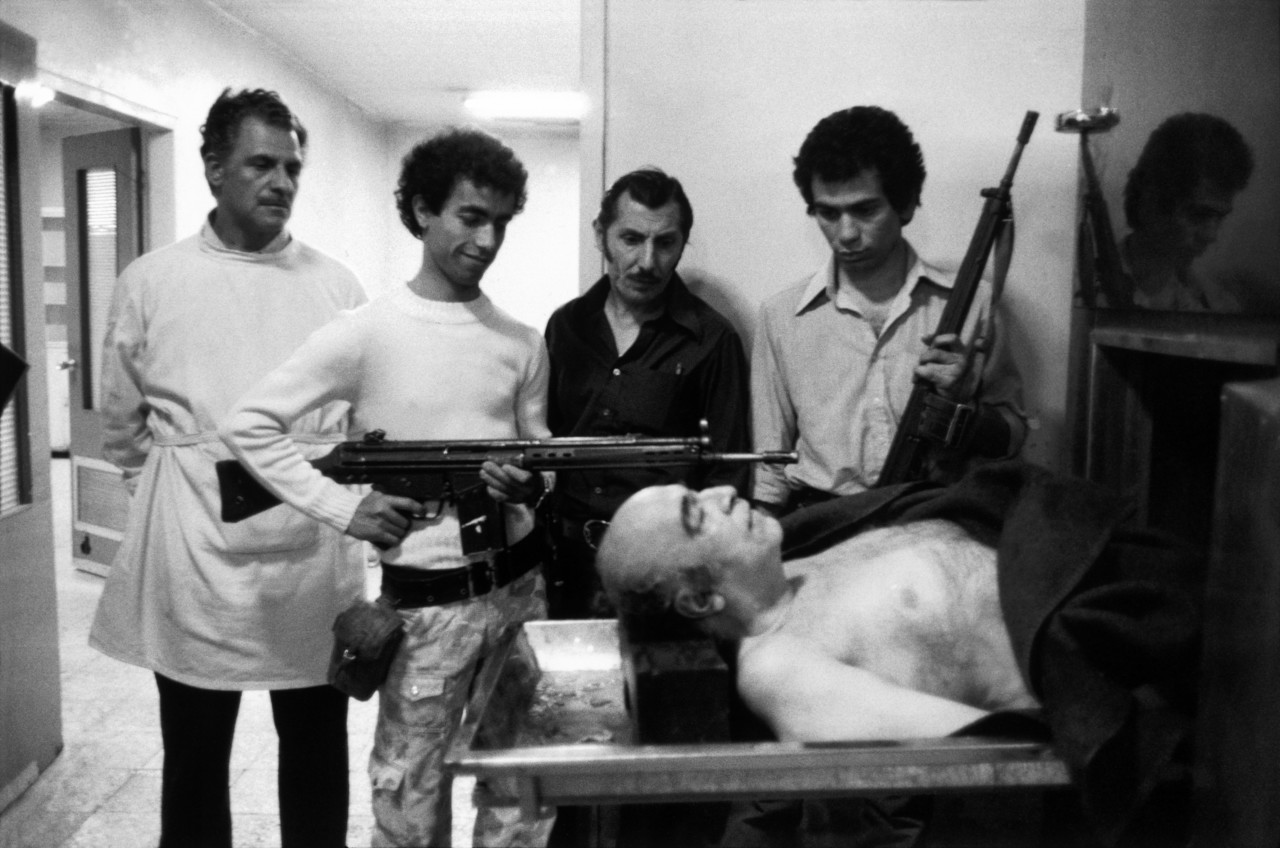

In the end they compromised: Pakdel suggested that Abbas break down his output into ten emotions, signaled by ten key photographs for discussion. Abbas instead picked ten themes that defined his oeuvre – violence, fanaticism, humiliation, pain, chaos, mockery, spirituality, beauty, sadness and private life – and chose ten images to illustrate each one.

Abbas’ preparation process took two to three months, but shooting, they decided, must be done in ten days. “He was suffering a lot, which was very hard for him and to watch, so we knew we’d have to shoot one theme a day,” Pakdel explains. “He was so stoic and determined to finish the film; he never once complained, but he was getting weaker and weaker and he died six days after we finished filming.”

Abbas told Pakdel to ask him questions, but the filmmaker, well aware of Abbas’ evasive nature, said that Abbas must lead the dialogue himself. And it proved a winning method. “Even his children said, ‘You’re probably the only person who could have done this,’” Pakdel says with an audible smile. “They also said it answered a lot of questions they had about their father. And that was really beautiful to hear.”

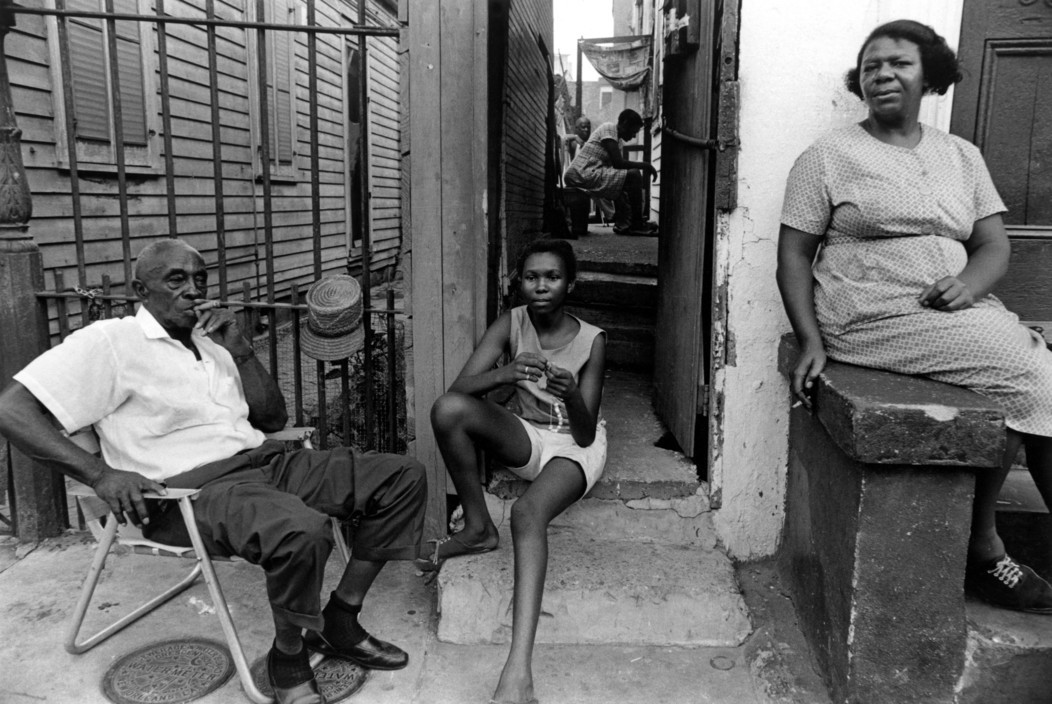

Abbas refers to his photographs as prompts throughout the film, beginning with a picture he took in 1968, of three family members sitting together on a front stoop, with two others talking in a passageway behind them. This image, he explains, confirmed his decision to pursue photography, capturing as it did a “suspended moment” – a phrase he would use throughout his career to explain his distinct mode of documentation. “I’m not freezing a situation, I’m suspending it,” he says sagely. “I want it to seem like the subjects kept doing things after the picture.”

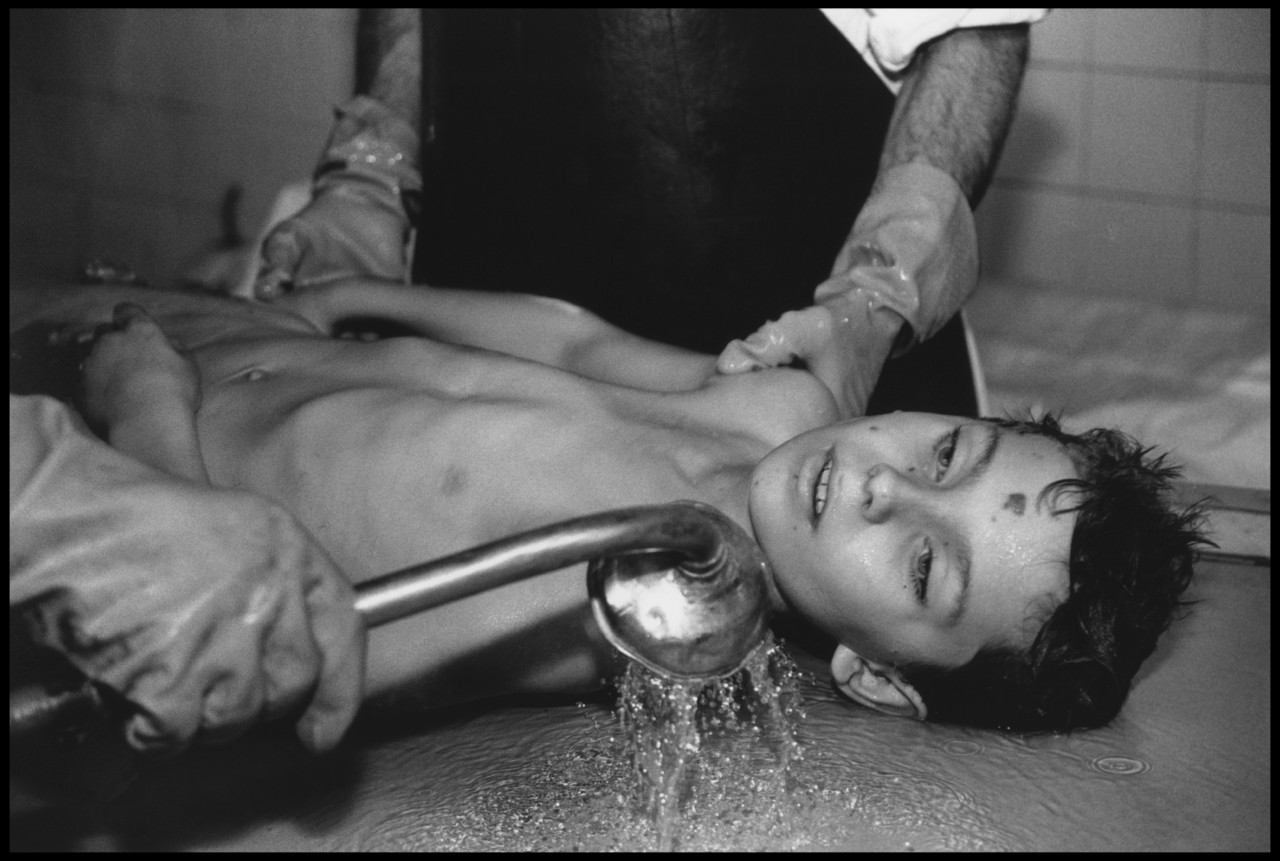

The film is dotted with insightful moments such as these, which offer profound insight into Abbas’ way of working and thinking as he approaches the end of more than six decades of image-making. One of his most heart-wrenching photographs – taken in 1993 and included under “violence” – shows the body of a young boy, killed in an explosion Sarajevo, as it’s washed down in a morgue. The eyes are still open, the face still animated. “You could see a boy still dreaming boyish dreams. I broke down [but] I kept taking photographs, of course,” Abbas says, showcasing both his innate empathy, and his overriding compulsion to document humanity at its most extreme.

"Abbas photographs as philosophers write. He doesn’t draw any conclusions; he doesn’t impose his point of view"

- Kamy Pakdel

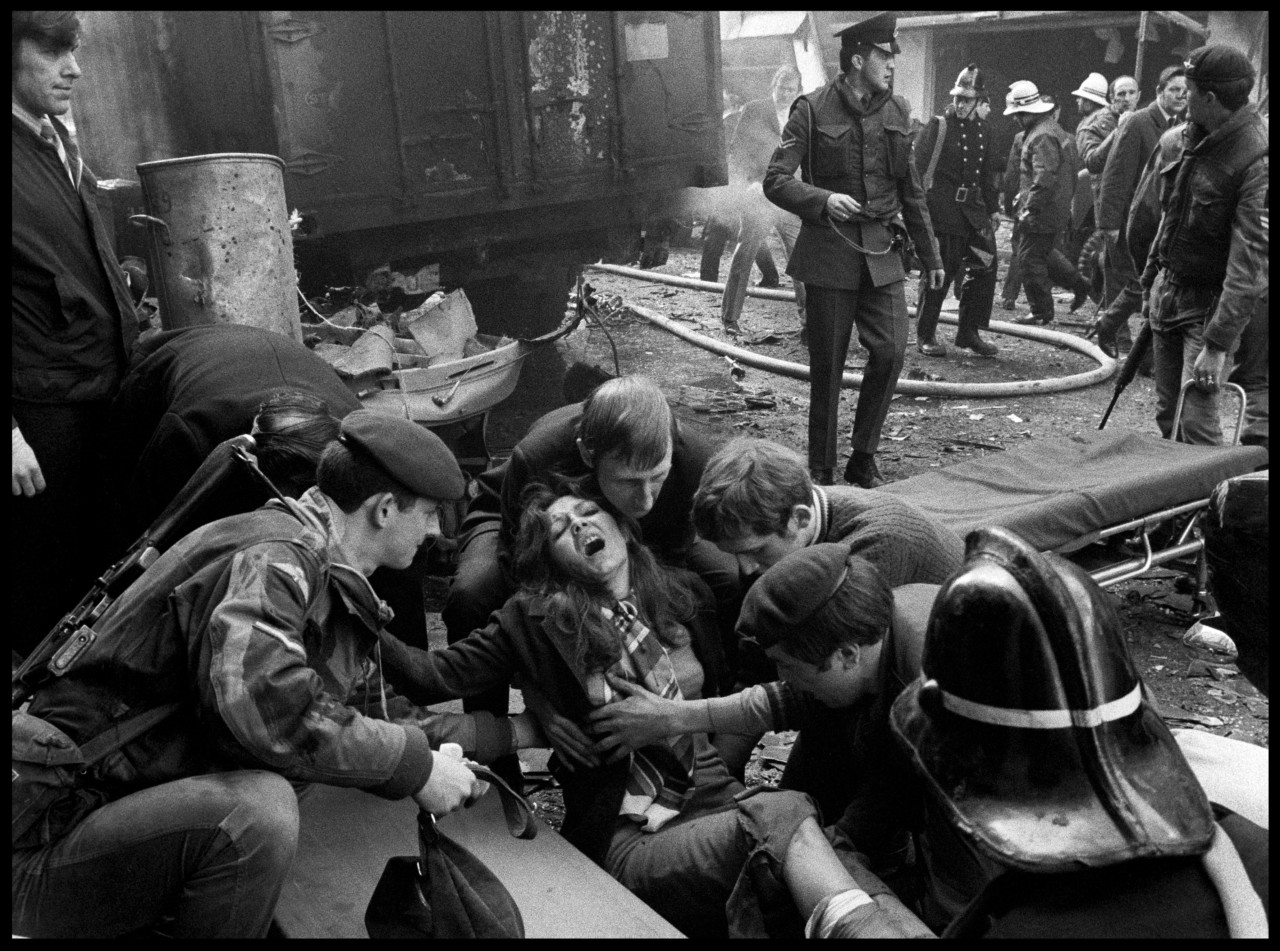

Another stirring image – shown in “pain” – depicts a woman injured by an IRA bomb in Northern Ireland in 1972. Her face is contorted in pain and she rests upon the outstretched arms of concerned bystanders who gather round her like mourners in a lamentation scene. The photo, Abbas says, demonstrates his interest in conveying universal themes through individual subjects. “Is it this one woman who is suffering or is her suffering symbolic of all those suffering during the war?”

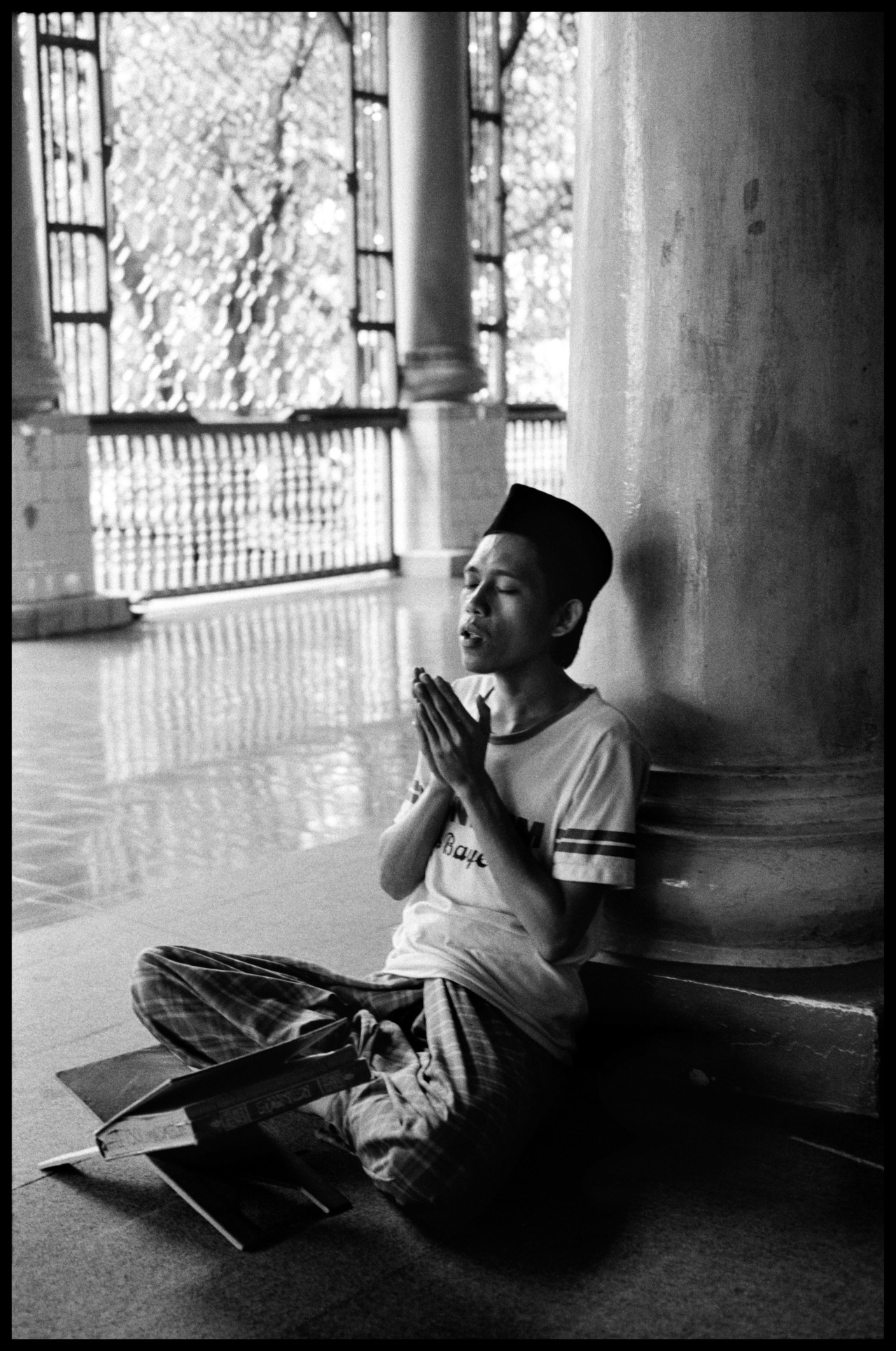

“Abbas photographs as philosophers write,” says Pakdel, musing on the power of the photographer’s work. “He doesn’t draw any conclusions; he doesn’t impose his point of view. He’s just questioning the human condition – questioning war, religions, beliefs. When I asked him during the ‘spirituality’ chapter, whether God did not exist for him. He said, ‘No, if there’s a single man or woman who believes in God, then God exists.’ It shows his great respect for others, his understanding of people. That was my favorite answer he gave – it’s so simple and deep at the same time.”

"If there’s a single man or woman who believes in God, then God exists"

- Abbas

Other chapters are lighter in tone, highlighting Abbas’ appreciation for “beauty” (a selection of lyrical, light-strewn works), for his “private life” (moving photographs of his treasured granddaughters), and for absurdity. “I love mockery,” he chuckles, looking at a series of preposterous photographs of Bokassa, President of the Central African Republic, who crowned himself Emperor on a golden throne, turning a blind eye to his country’s extreme poverty. “He walked by the toilets [in his ermine and crown]. I couldn’t miss the chance [to mock him].”

"Let the photos live their lives and keep their mystery"

- Abbas

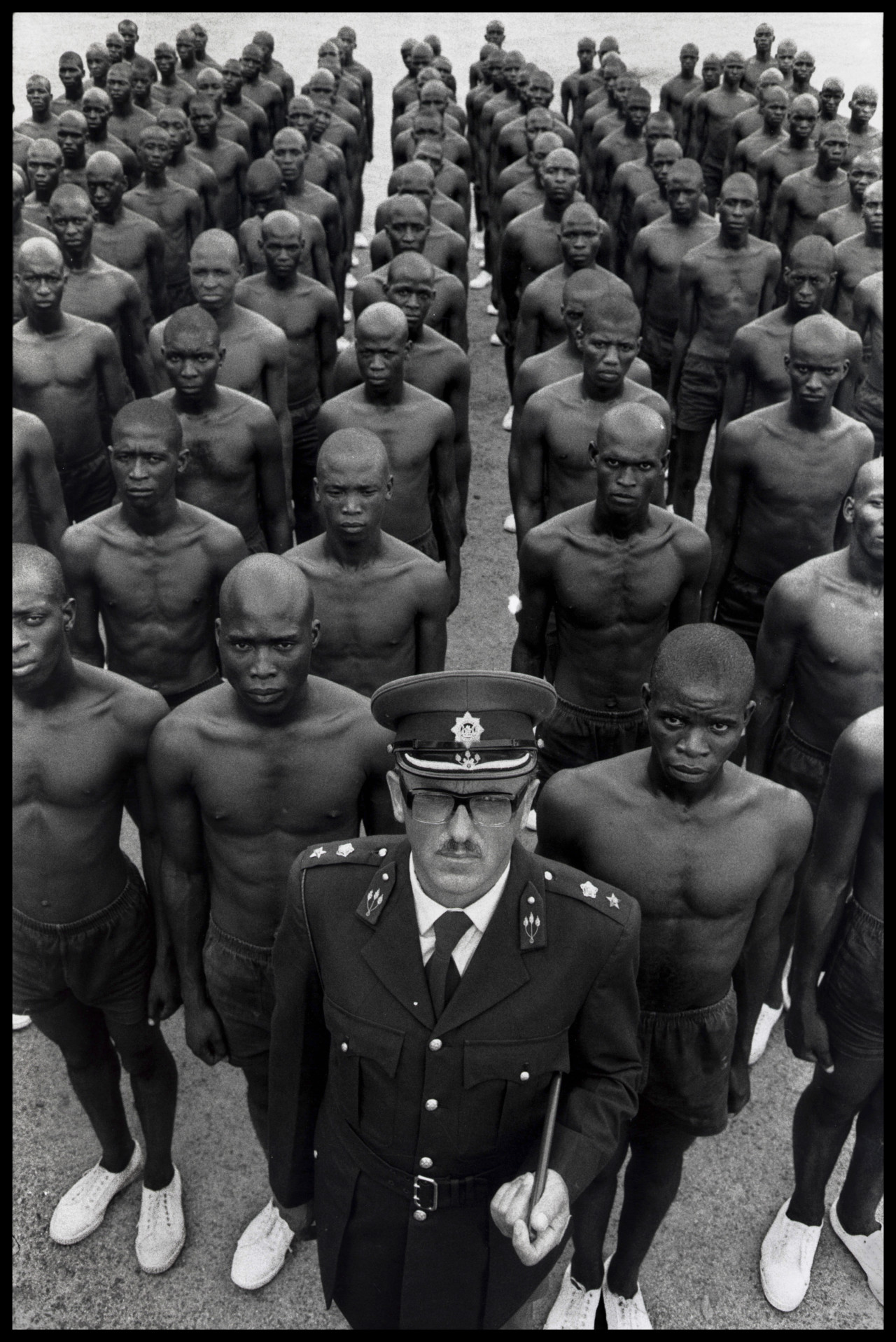

The documentary frequently affirms this impeccable sense of timing and composition. From the seminal photo that came to symbolize the apartheid in South Africa – a white colonel from the black police academy, standing grandly in his uniform before his trainees, who are lined up behind him in rows, wearing nothing but shorts and plimsols – to his image of a young man who had fainted during the first anniversary celebrations of the Islamic Revolution. Crowds hold him aloft above the dense crowd, while a descending fog seeps the scene in mysticism. Pakdel – posing a rare question – asks how he got the shot, but Abbas just shakes his head. “Let the photos live their lives and keep their mystery.”

As our conversation draws to an end, Pakdel remembers something important he wants to add: that Abbas refused to redo any of the takes. “Once I said, ‘Abbas, that was really interesting but I don’t think we captured it quite right, can you repeat it?’ And he said, ‘This is not a film for the cinema: you’ve got one shot, you’d better get it’” – a phrase that could just as easily be read as a motto for photojournalism, and which undoubtedly resulted in the remarkable collection of suspended moments from across the globe that Abbas leaves behind.