Albania: A Homecoming

Enri Canaj shares the story of his life, career, and practice during a workshop in his hometown of Tirana, Albania

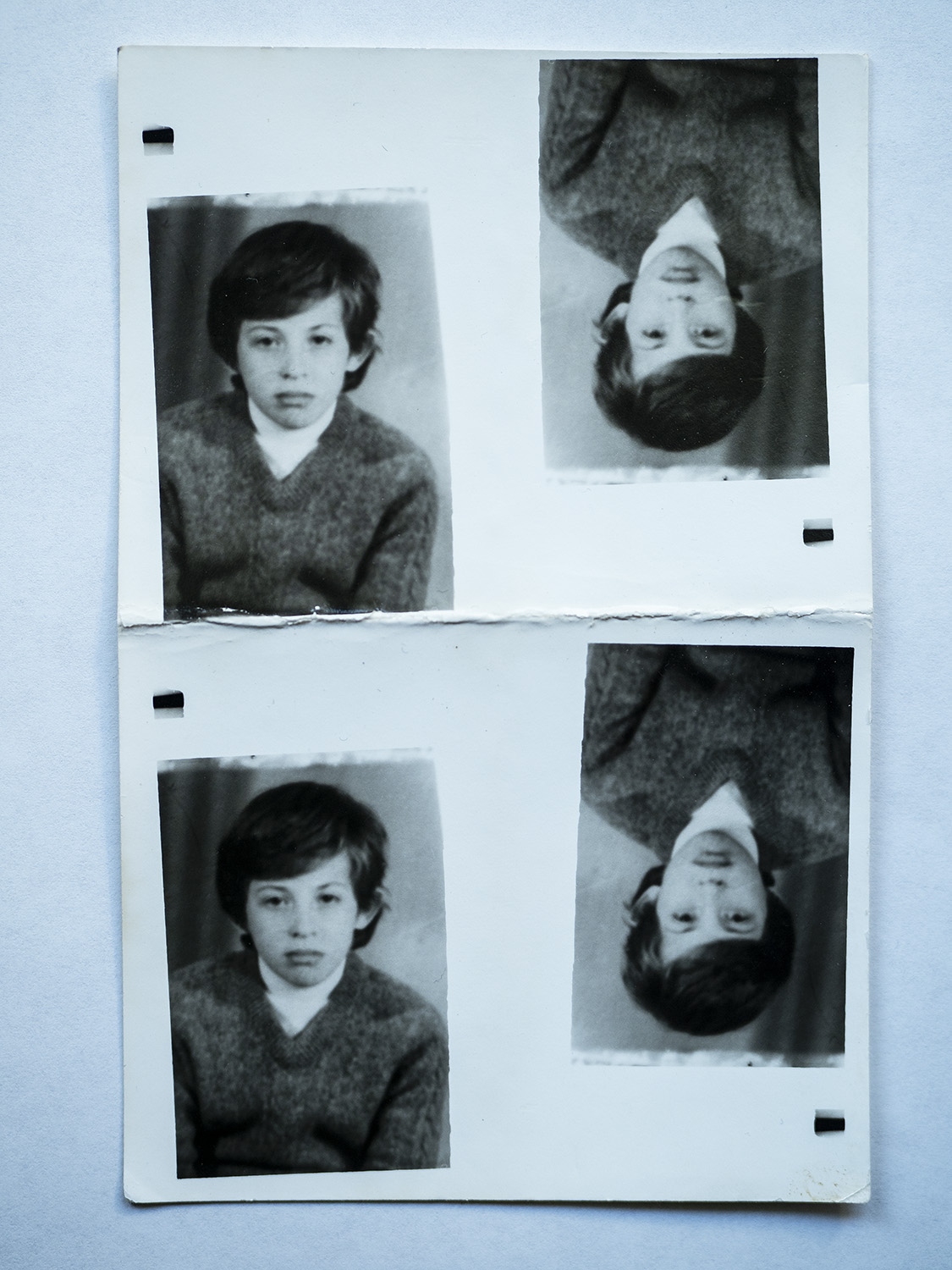

Enri Canaj sits on stage at the Agimi Cinema in central Tirana, the crowd before him quiet and attentive as he flicks through early images of his childhood on the big screen. The first image is a family portrait, shot in the city’s Skanderbeg Square in the 80s. “None of us had a camera to take photos,” he explains. “The only images we have are ones that were taken in public spaces. Many of my friends have the same family portrait in this same spot.”

Canaj was born in the Albanian capital in 1980. The country was 36 years into Enver Hoxha’s brutal communist regime, long cordoned off from the rest of the world and deprived of the freedom to travel, freedom of speech, and freedom of religion. It wasn’t until 1990, under Hoxha’s successor Ramiz Alia’s rulership, that Albanians were granted the freedom to travel abroad for the first time in five decades.

In 1991, at the age of 11, Canaj’s life was set on an alternative course to that of his peers. Following the collapse of the communist regime, his parents decided to pack their few belongings and move to Athens, Greece. “One of the only things we took was the box of photographs,” he recalls.

Life in Athens was difficult. Leaving their home, belongings, and community behind, the family found themselves living out of one room in a cheap hotel. For the first decade of their new lives, the family were stuck in Greece, unwelcome and unable to return to their homeland.

“I had to grow up fast,” he remembers. In one image, we see him at 12 years old holding a basket of sesame bread rings, known as kuluri, a local delicacy. “I didn’t know what to do with my time. My parents never told me to go and work but I’d understood the situation — it was a difficult one.” One morning, he went to a bakery and asked if he could take a basket of bread and sell it on the streets. They accepted, and it was as such that he found his first job, and first sense of purpose, at such a young age. “I would wake up every day at 6 a.m. and go to sell the bread. I found a way to do something, and I was happy.”

Listening to Canaj telling the story of his life and journey to photography, especially his early years, is a rare occasion. Now in his 40s, the photographer is still based in Greece, but travels regularly to his homeland and often splits his time between Athens and Tirana. In the audience are several of his Magnum colleagues, Mark Power, Bieke Depoorter, Newsha Tavakolian, Sohrab Hura, Jérôme Sessini, and the participants of the Inside>>Out workshop, hosted in the Albanian capital that week.

It is the first time a Magnum Learn initiative has taken place in Albania, and marks the largest and most ambitious Magnum workshop to date, encompassing six separate workshops with six Magnum photographers, and sixty-plus participants from around the world, including eleven scholars from the Balkans peninsula. Each evening, after spending the day with their respective tutors, the full group would gather at the Agimi Cinema for a talk from one of the Magnum photographers.

As the talk goes on, the images projected begin to change from family memorabilia to starkly contrasted black-and-white images of the dark streets of Athens. Canaj goes on to describe how he came to photography, completely by chance, at the age of 20, when he found a job at a gallery that exhibited a selection of photographs. “I thought the images were beautiful and I immediately told my new employer that I wanted to be a photographer. He said that I was crazy, that I would make no money. But he still shared his darkroom with me.”

"As an immigrant, you think that nothing belongs to you. But when I took the camera, I felt like I was in the center. Photography was kind of a step to explore myself too. "

-

Photography was by no means the easy option for the young Canaj, who at the time lived in the Omonia neighborhood of central Athens, and had only that year legally become an official citizen of his adoptive country. But as someone who had grown up quickly in a strange and unfamiliar place, there was something about the camera that, despite the impracticality of the career path, became his passion and purpose, resurfacing the same determination that he had shown as a 12-year-old selling kuluri in the streets of Athens.

“As an immigrant, you think that nothing belongs to you,” he explains. “But when I took the camera, I felt like I was in the center. Photography was kind of a step to explore myself too, or to understand. The project was to document the area, but the deeper project was to understand who I am.”

For the first decade of his career, from 2001 to 2012, Canaj spent his days roaming the streets and back alleys of the city, returning home each evening to the makeshift darkroom in his bathroom. With his camera, he documented the dark underbelly of the Greek capital, the modern-day society living in the shadows of ancient civilization.

It was a time of immense change for the city. With the advent of the Olympic Games in 2004, he describes how the city’s population began to change, and with the financial crisis, which came to a head in 2007, the city became an increasingly dangerous place to be. “It became hard to survive. Newspaper assignments wouldn’t be paid for six to seven months. Shops were closing, the city became very dark, and there were clashes every day.”

And in 2012, Canaj shifted his lens away from Athens itself and toward the early days of the refugee crisis. “I had no assignments, and didn’t know exactly what to do,” he explains. “But I wanted to go out and find a way to capture the situation. But after 2014, up to 100 boats were arriving on the Greek Islands every day. And I started photographing.”

Canaj embarked on the project by traveling extensively from Lesbos to Turkey, and the borders between the Balkans and Europe. His images are dark, tragic, showing the pain and suffering of asylum seekers who had lost everything through a raw, unfiltered lens, perhaps in stark response to the desensitized accounts presented by Western media at the time. Canaj spent time with groups as they attempted dangerous border crossings, often in confrontations with police forces.

One image from the final edit comes up large on the cinema screen as Canaj begins to talk about the series. It shows an Afghan family in the remains of the ruins of Moria, the biggest refugee camp in Europe, home at one stage to over 20,000 people, and victim of a widespread and obliterating fire in 2020. “It was lucky that no one died,” says Canaj. “This family returned in the following days to try and find the little that they had lost.”

The project slowly developed into what we now know as his first monograph, Say Goodbye Before You Leave. Published in 2022, the book is a documentation of people’s journeys, struggles, hopes and dreams across 3 continents, 13 countries and 25 cities and towns in western and northern Europe. It is a study of migration over three phases: the arrival, the first years, and the situations of those still waiting on the other side. “All of this was very familiar,” he writes in the book’s afterword. “The present walked in parallel with my past.”

"When you leave something behind, suddenly it feels like the umbilical cord has been cut. All the same, you don’t have time to say goodbye; you must go on and embrace the pain within."

-

Hearing Canaj talking about his own life gives valuable context to his decision to spend eight years documenting the immense danger and harshness for asylum seekers at the time. “I was 11 years old when my parents decided we had to leave our country. When you leave something behind, suddenly it feels like the umbilical cord has been cut. All the same, you don’t have time to say goodbye; you must go on and embrace the pain within.”

Fast forward to today, and Canaj has become a well-recognized face in the arts scene of his hometown, as is clear from the groups of people milling around before and after his talk. One morning during the week, he is found hiding in one of the booths at the very back of a long, indistinct café to complete some urgent work for a project with Polaroid. “If I go to Destil [an arts center and one of the workshop locations], I will never get anything done,” he laughs. “There will be too many people that I know.”

It was in 2001 that Canaj first returned to Tirana, and Albania. Now, he tells the audience how photographing in the city of his birth was initially very difficult. “I had no experience at that time, and the pictures were not good,” he laughs. But he returned in 2007, and there the fact of shooting in his homeland took on a new dimension, in contrast to the darkness we find in his early work in Greece.

"To tell the truth, what I had kept of Albania was not specific moments, but more of a fantasy. So the pictures I took are a lot more abstract."

-

“What I left behind in Albania was a lot of sweet memories, so when I had a difficult time in Greece I would think of that. I decided to go back to Albania to find what I missed while I was far away. The people here are nice, and I felt like I was exploring myself. So photographing there became so much fun,” he describes. “To tell the truth, what I had kept of Albania was not specific moments, but more of a fantasy. So the pictures I took are a lot more abstract.”

Canaj ends the talk by bringing together the different elements of his archive, defining his subject matter as an exploration of our relationship to familiar and unfamiliar places, unpacking a sense of belonging and what the word “home” could possibly mean. “The main projects that I took and crafted have been about Greece, Albania, the homeland that I left behind, and immigration,” he concludes.

The following day, Canaj is teaching a class on the 23rd floor of the Sky Tower, a high-rise constructed at the turn of the century and now home to various businesses, consulting firms, and high-end galleries. Titled “On the Road,” it is a shooting workshop, and this morning the group of 11 participants are going through the images shot the day before in Durrës and central Tirana. Canaj is cool, calm, collected as he walks into the room wearing his trademark slightly oversized denim jacket and red baseball cap. “How was it yesterday?” he asks the group with a smile on his face. “Did you make something?”

The participants are three days into the six-day workshop but seem as if they have known each other, and Enri, for much longer as they go through each other’s images. As a tutor, it does not take long to see that he is easygoing, but honest. “I don’t like this one,” he says to one participant. “There is nothing interesting in this picture.” Then, as the slide changes: “This one is much more interesting. This is a very nice portrait. Brava.”

“I’m a self-taught photographer, so I’m not used to sharing my work with anyone other than my friends, who don’t know anything about photography,” one of the participants laughs. “So it was stressful to show my pictures to Enri at the beginning. I spent the whole night before editing and trying to make it perfect. But it wasn’t as stressful as I thought, we had a good discussion, and then I felt much more confident afterward. He’s a very nice guy. Very down to earth. When I speak to him, I feel like I’m speaking to a friend.”

“It is not about perfect pictures. It is about interesting pictures,” he interjects mid-way through the morning as another participant describes the struggle to find the perfect composition for one of her photographs the day before. “Perfect is sometimes boring. Don’t think too much about it. Small mistakes are interesting. Surprising.”

Spending time with Canaj reveals the dichotomy between his affable nature and the depth and intensity of his photographs. These layers are perhaps what form the duality of his nature as a tutor: incredibly kind, but totally frank. He has the rare capacity to deliver criticism constructively and without a cutting edge, exposing his empathy as a human, not just as a photographer.

Enri Canaj will be hosting another workshop, titled Journey Through the Greek Islands, from September 22 to 27. Open to photographers of all levels, from passionate amateurs to working professionals who want to further refine their skills in the art of street photography, the workshop will take participants on a voyage through the islands of Sifnos and Milos. A few spots remain. More here.