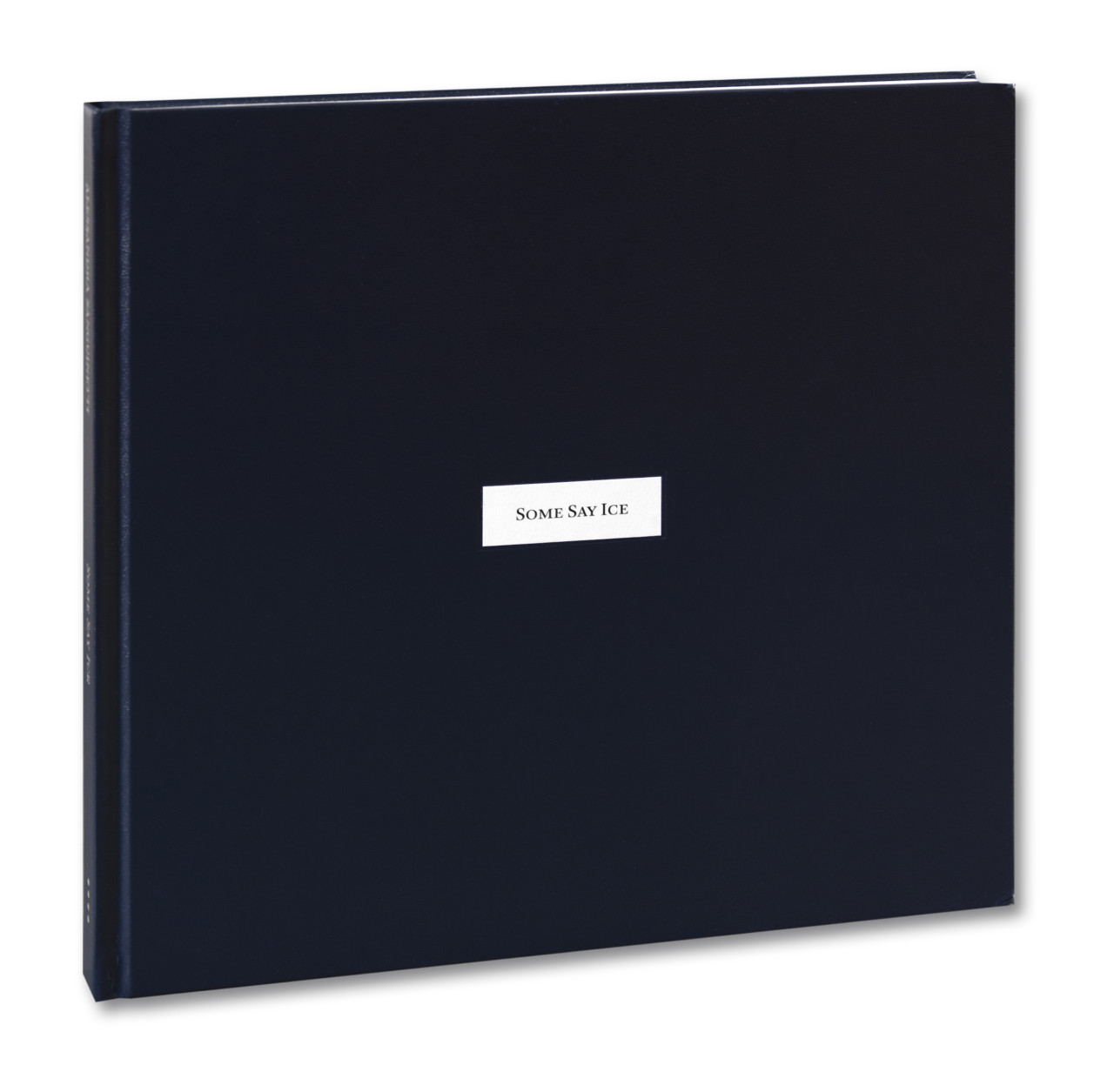

Some Say Ice

Alessandra Sanguinetti's Some Say Ice is currently on view at the Magnum Gallery in Paris. Below, she talks to Allie Haeusslein about how the project came to life.

At age nine, Alessandra Sanguinetti stumbled across a copy of Michael Lesy’s Wisconsin Death Trip on the bookshelves of her family’s home in Buenos Aires. The macabre, cult classic of historical non-fiction, first published in 1973, portrays Black River Falls and its environs at the turn of the 20th Century. Interweaving contemporaneous images from photographer Charles Van Schaick with clippings from local newspapers and other ephemera, the book offers a harrowing depiction of strange goings on in the rural Midwest.

Sanguinetti credits this early encounter as the moment she first acknowledged her own mortality and that of everyone she loved.

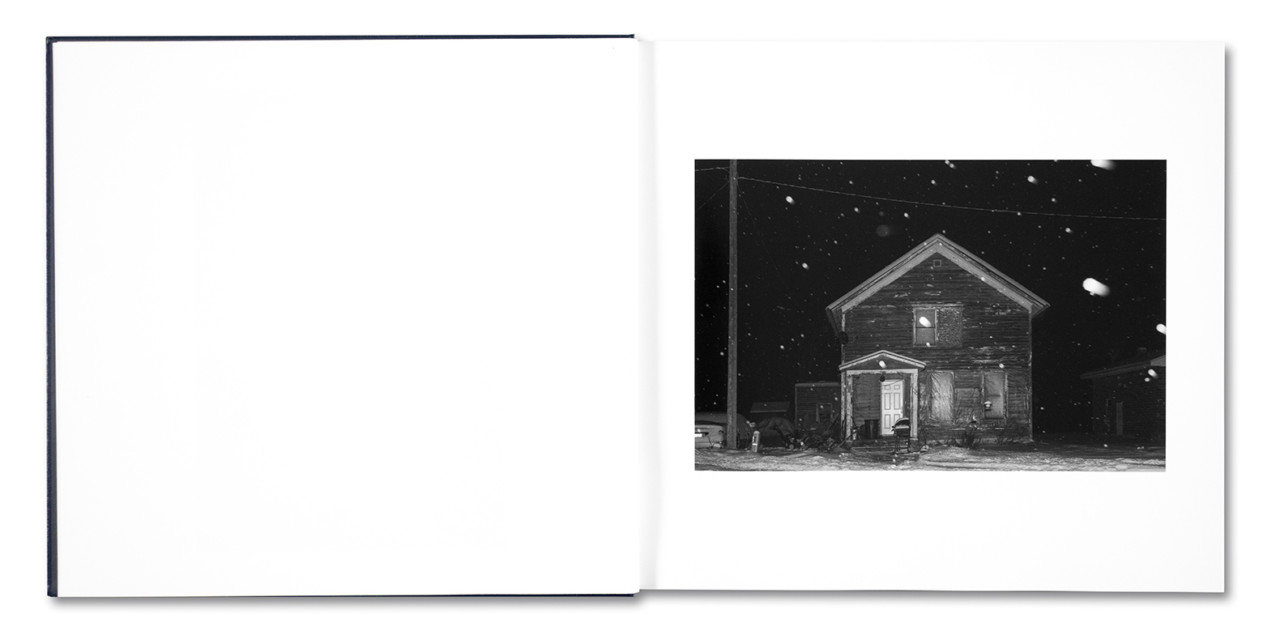

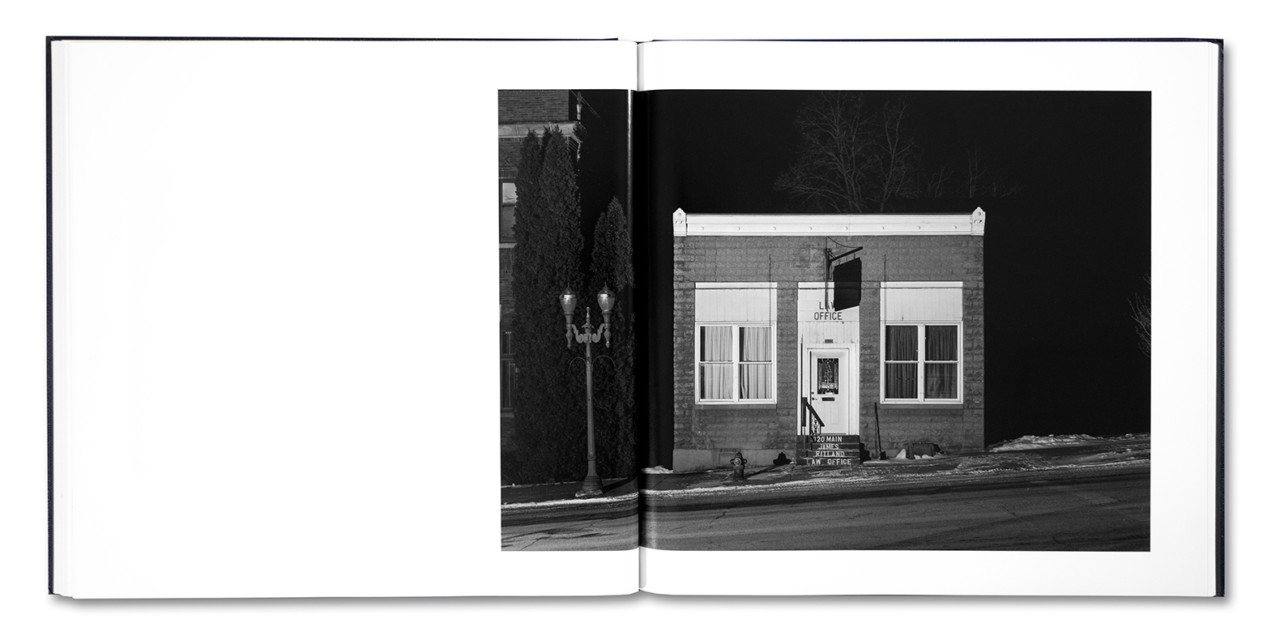

Nearly 40 years later – and over a century since Van Schaick made his images – she ventured to the fabled town, photographing Black River Falls and the surrounding region. From 2014 to 2022, Sanguinetti documented the people, places, and rituals of these communities, blending a tender curiosity with an underlying gothic sensibility.

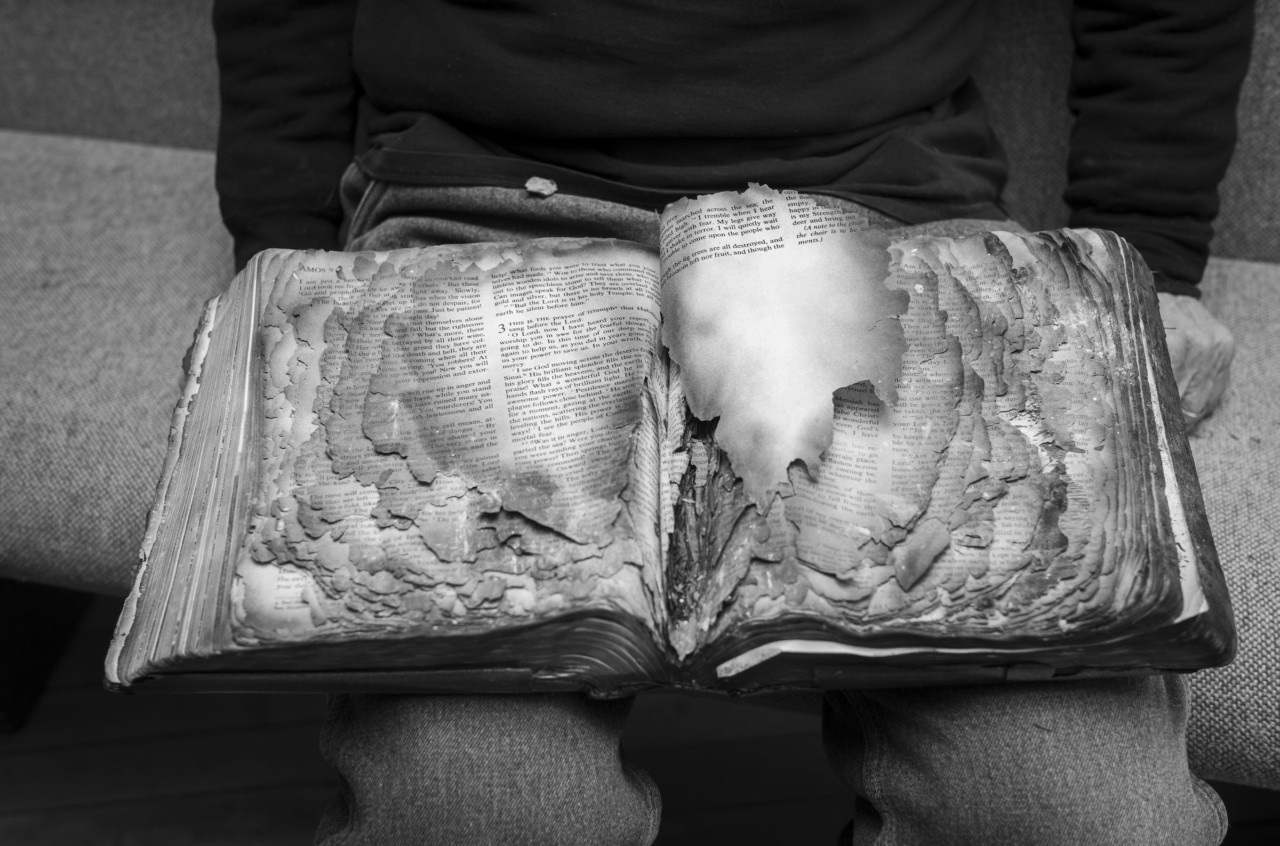

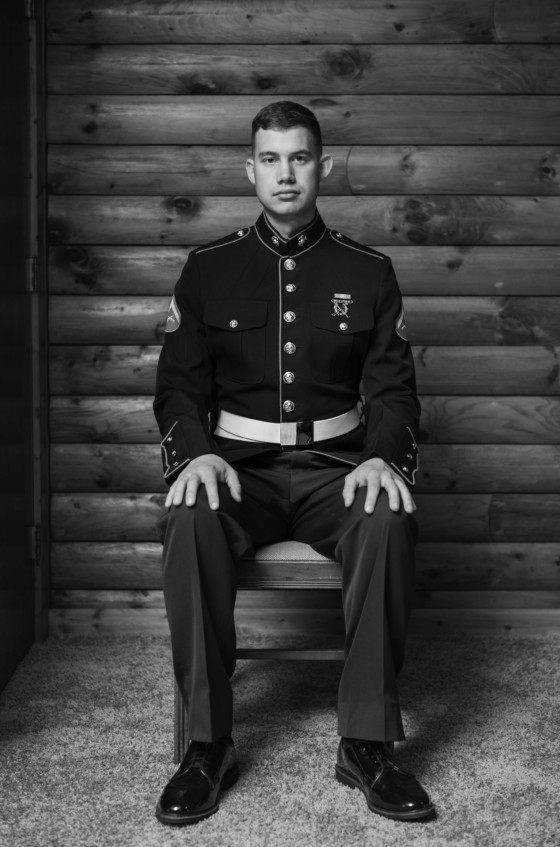

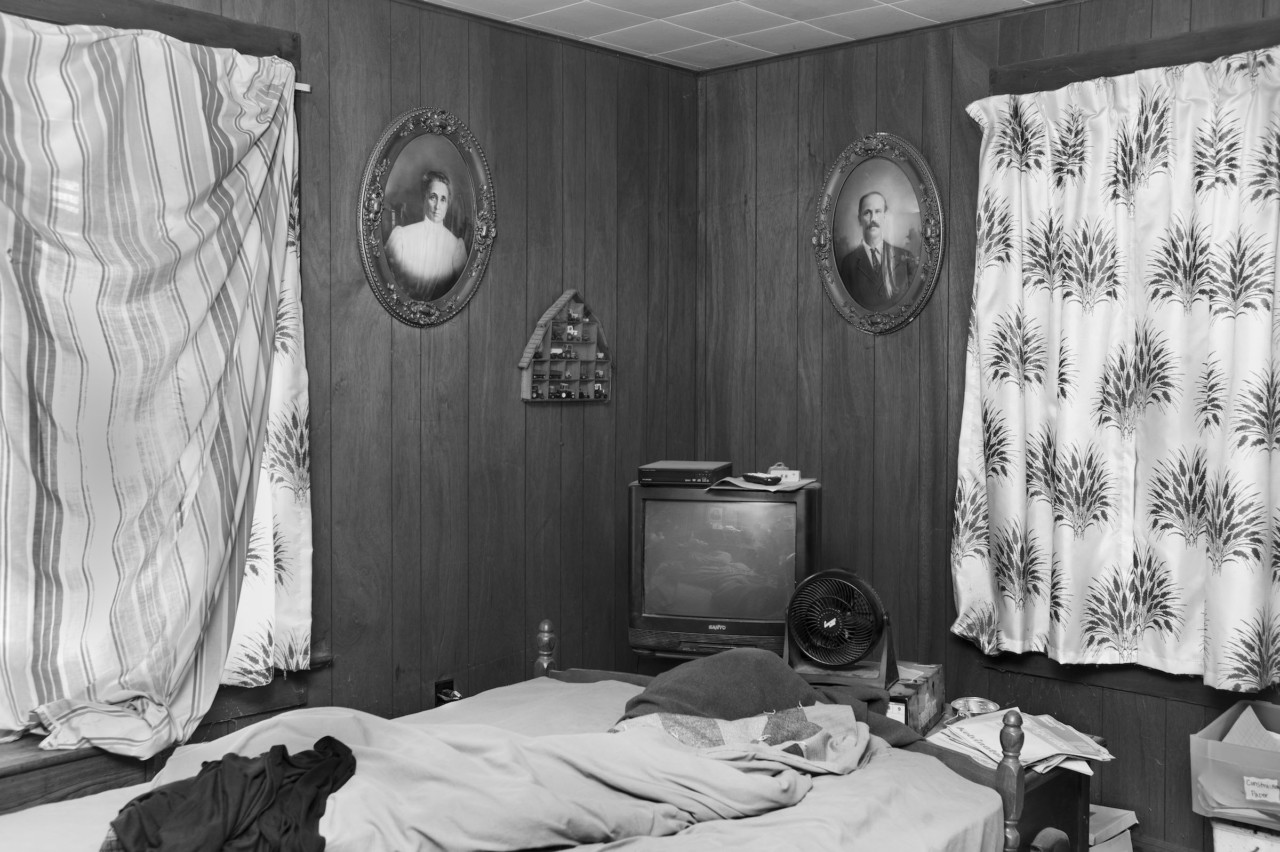

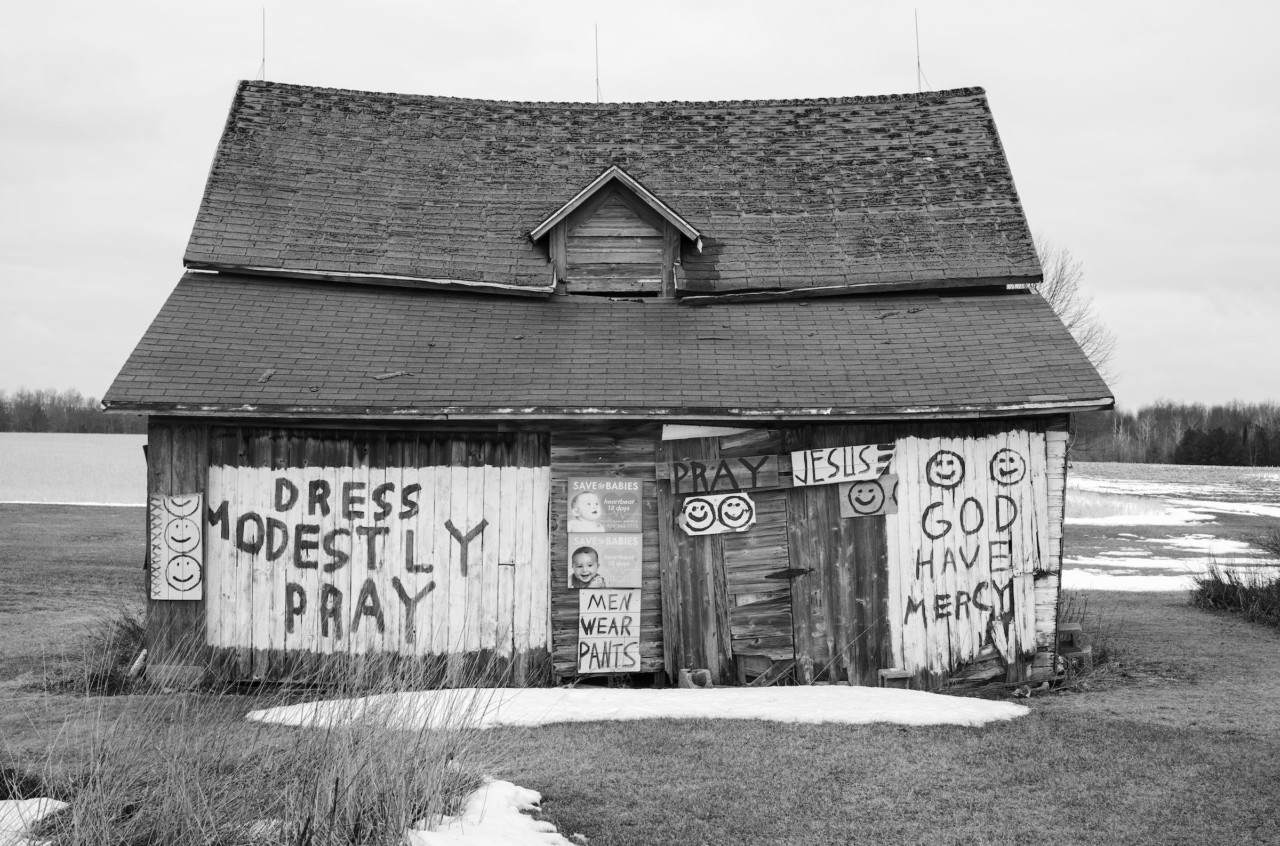

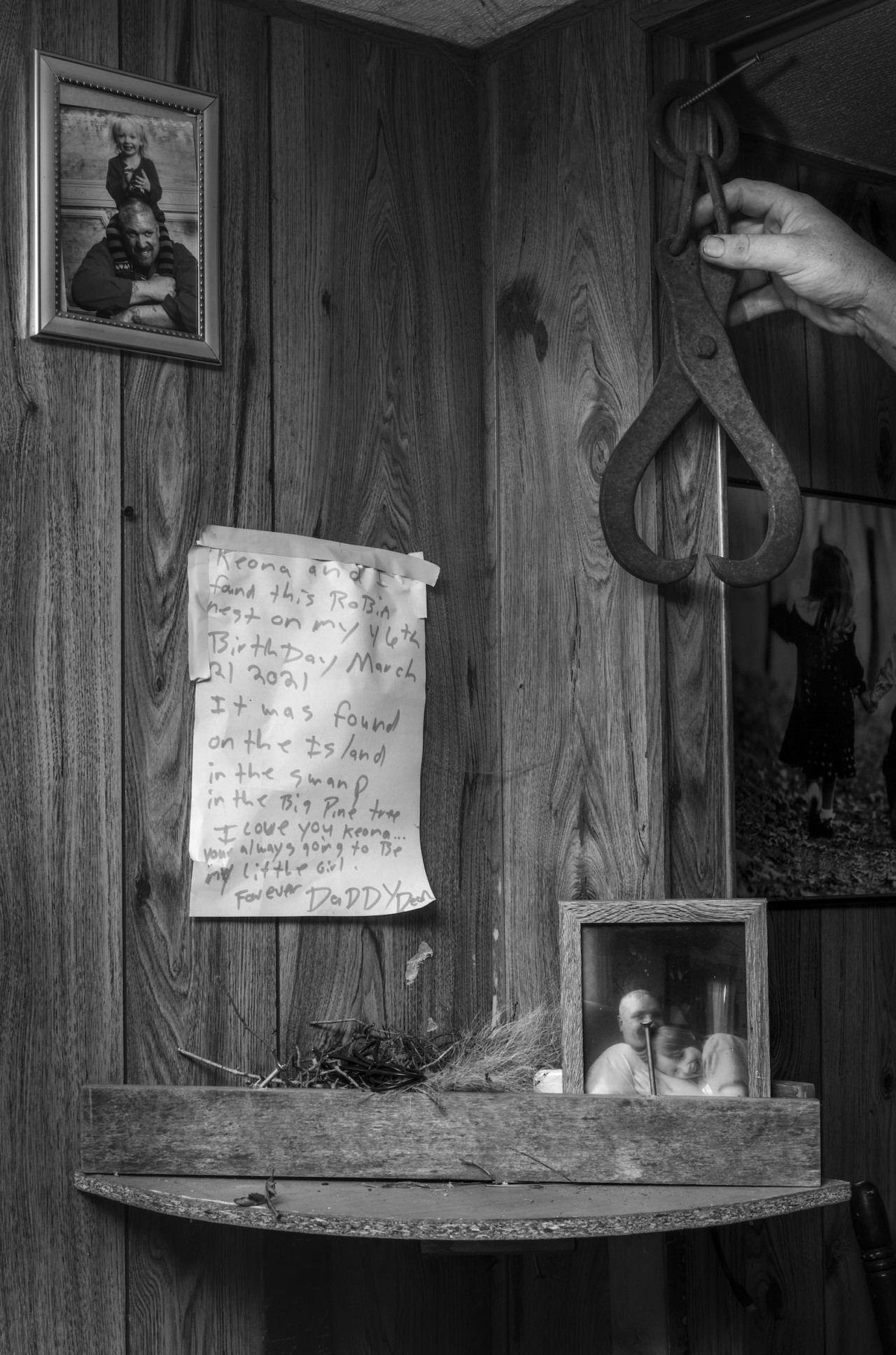

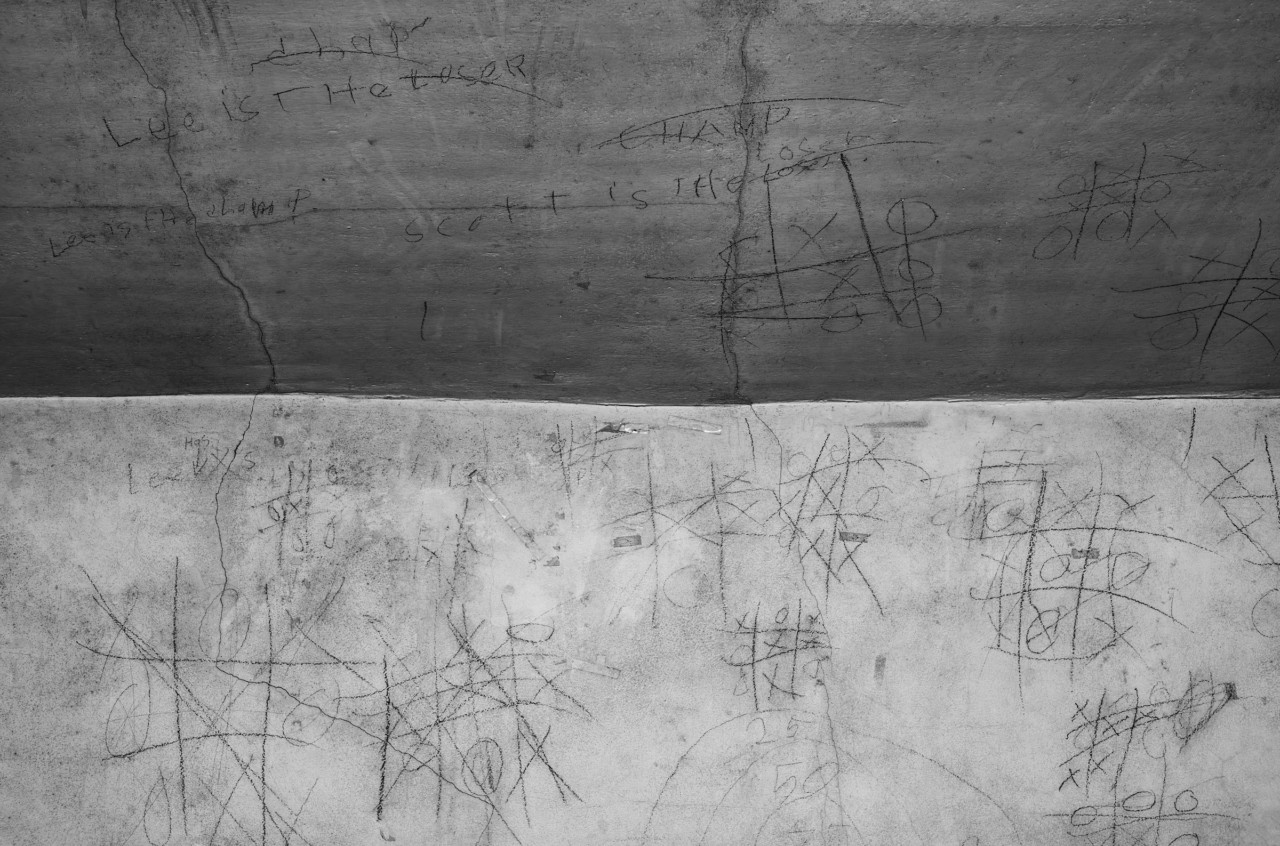

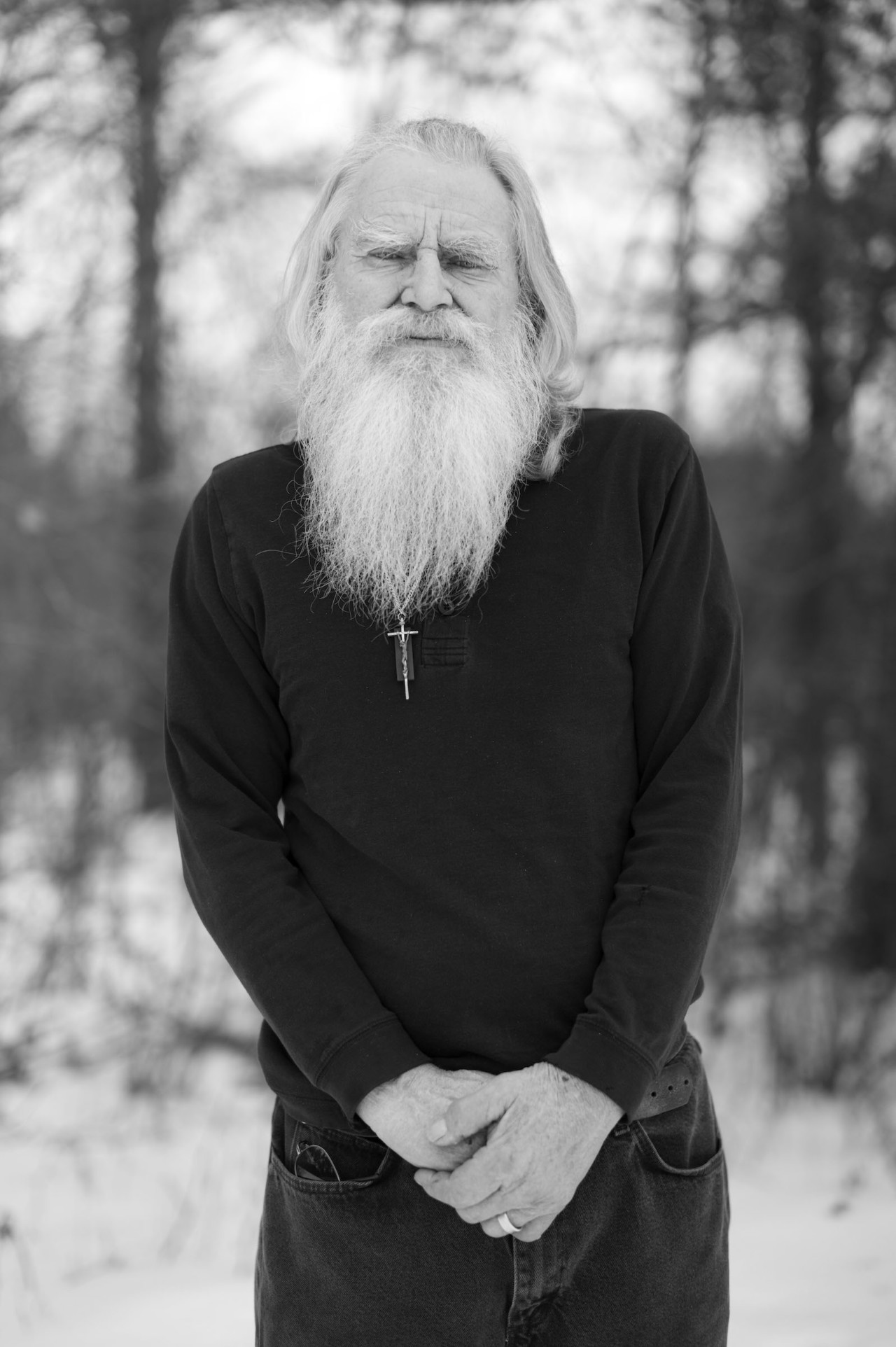

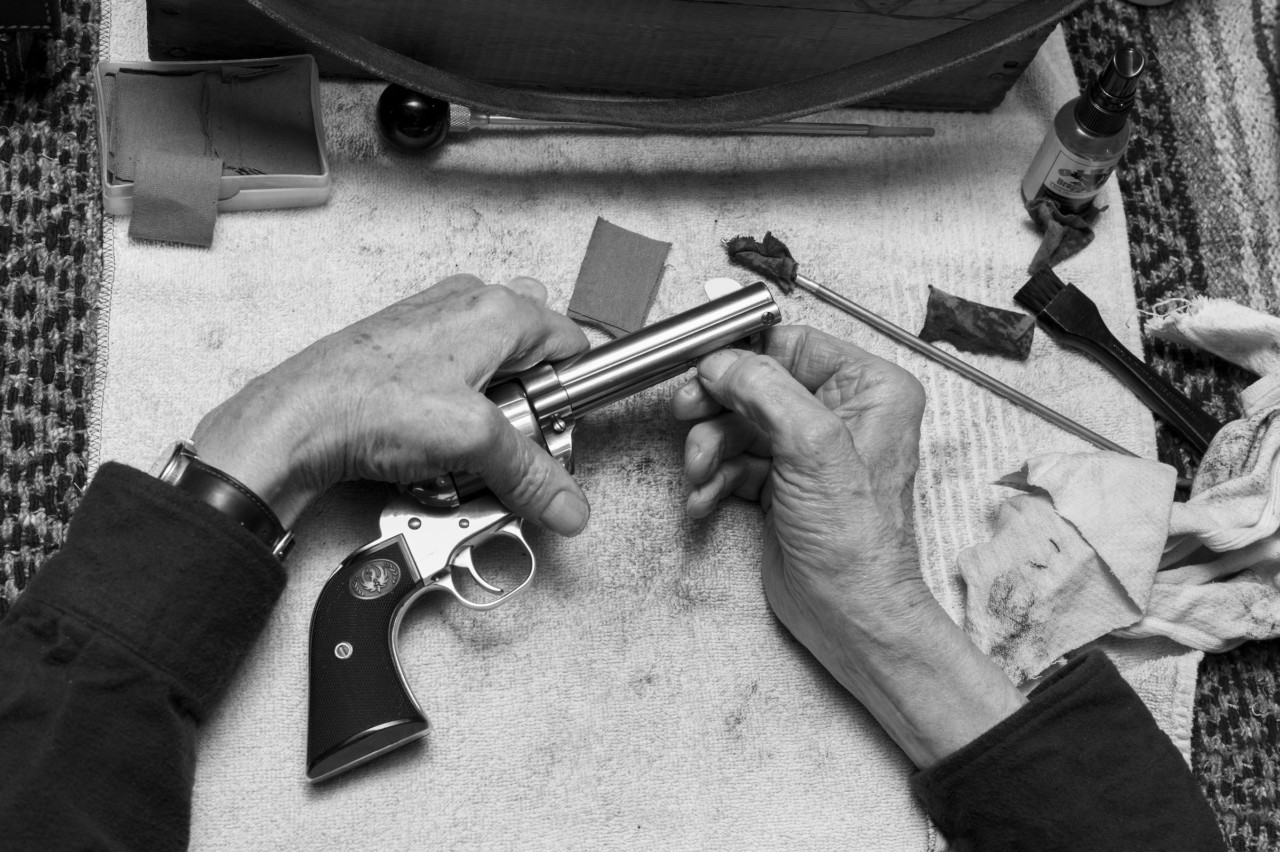

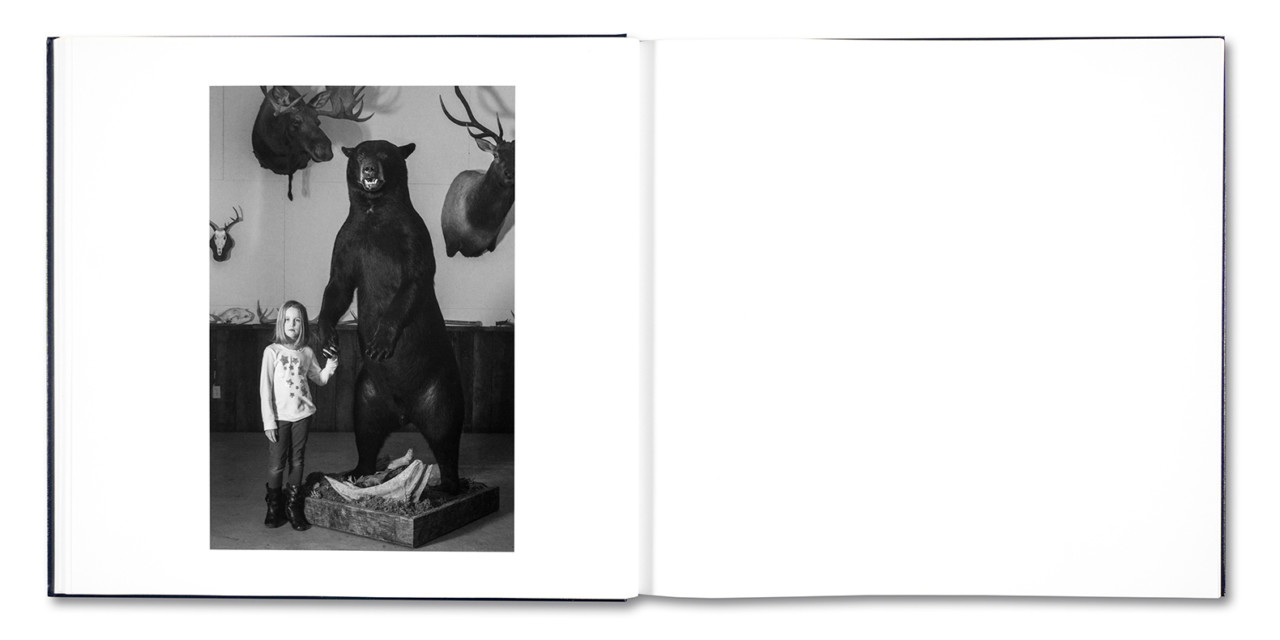

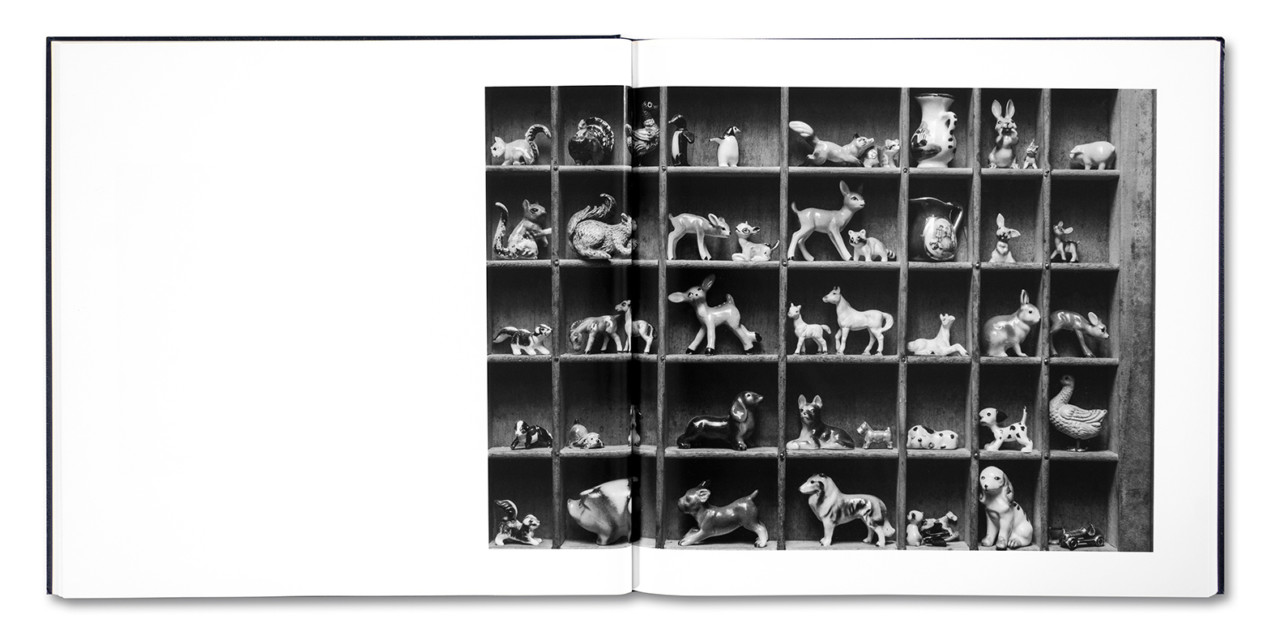

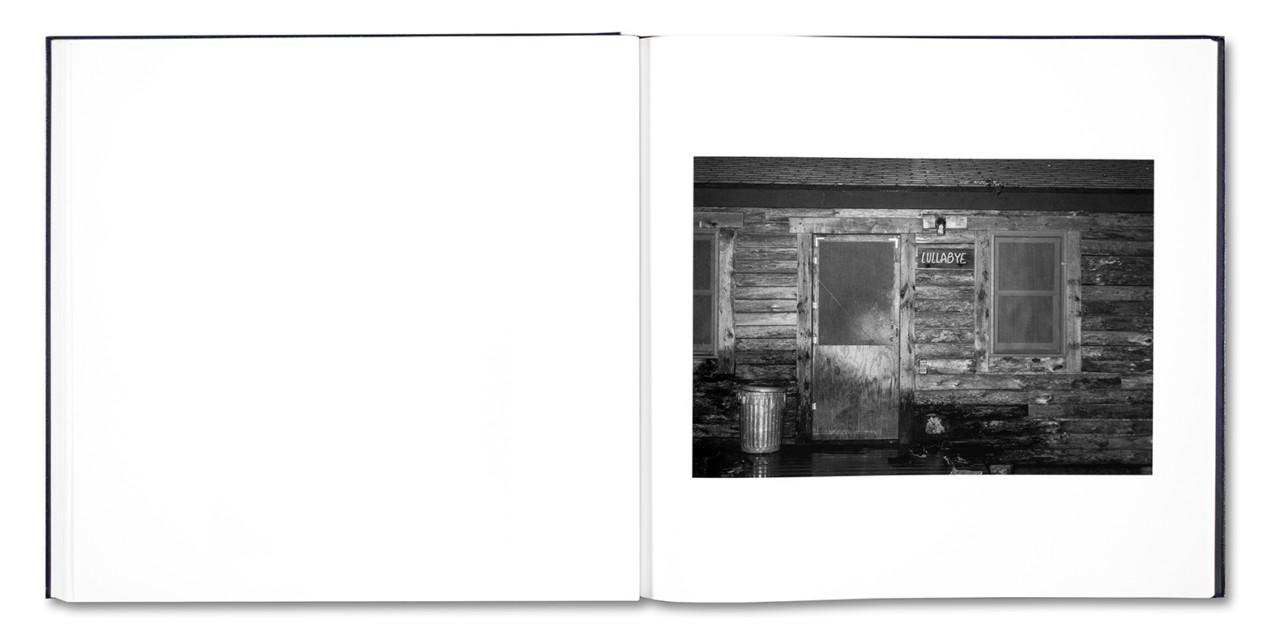

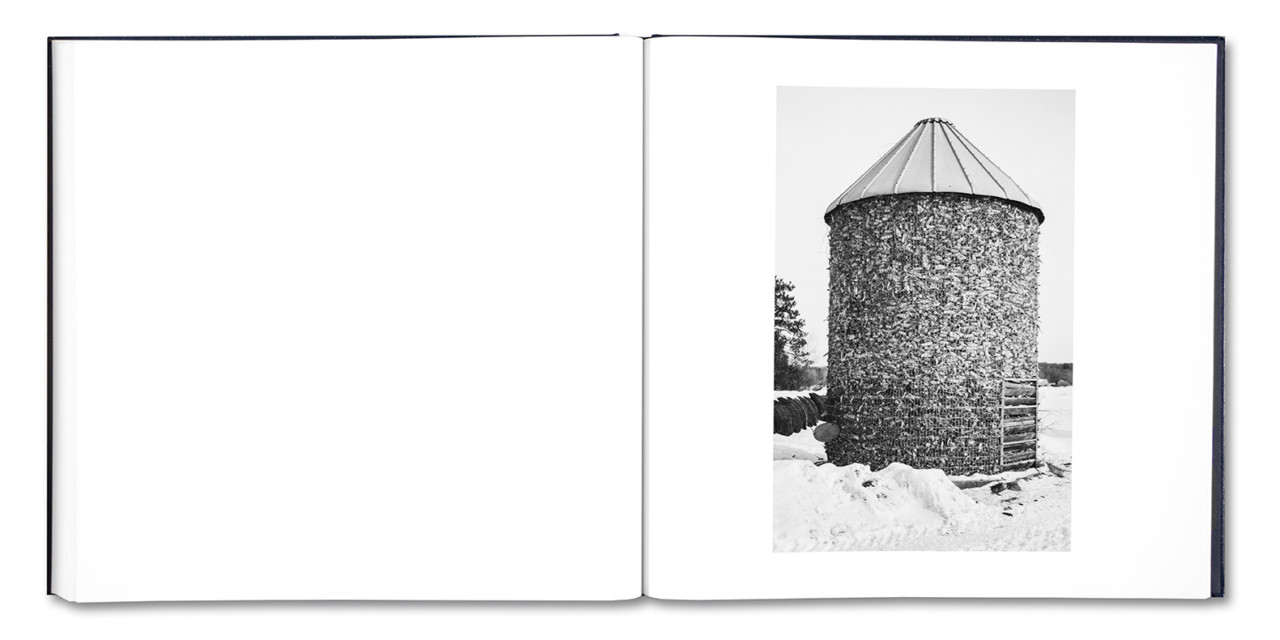

Some Say Ice, published this fall by Mack, appropriately takes its name from Robert Frost’s Fire and Ice (1920), a pithy, apocalyptic poem envisioning the end of the world. Stoicism characterizes every face, young and old. Timeworn buildings with wood-clad interiors populate the eerily unpeopled roads. The pictures are suffused with a bitter cold and the sensation that time stands still. And throughout, intimations of death and violence feel inescapable.

The haunting, uneasy narrative that unfolds in Some Say Ice captivates with its enigmatic tempo and tenor, speaking poignantly about the kinds of communities and lives that rarely make headlines in the US.

Signed copies of Some Say Ice are available from the Magnum shop.

Allie Haeusslein: What impact did seeing Wisconsin Death Trip have on you as a young person?

Alessandra Sanguinetti: Many books around my childhood home made a big impression on me. Among them, books of photographs by Chim (David Seymour), Dorothea Lange, and Jacques Henri Lartigue, along with The Best of Life [also published in 1973, pulling together iconic photographs that appeared in the golden days of the weekly illustrated magazine] and, of course, Wisconsin Death Trip, which as you know inspired Some Say Ice.

The edit of Wisconsin Death Trip has a kaleidoscopic feel to it, like a house of mirrors, which makes it very immersive. I distinctly remember the dread filling me when I saw a photograph of an impossibly old woman followed by an image of a dead little girl in a coffin with a faceless man standing by her. I suddenly and without question understood that death was real and would happen to me.

My response to this realization was to ask for a camera.

What are some of your earliest memories with that first camera? At what point did you realize you wanted to spend your life making photographs?

It was a Kodak Instamatic with those old flash bulbs that would burn out after one pop. The film and flash bulbs were really pricey in Buenos Aires, so I’d have to make a roll last for months, thinking very carefully about what I photographed.

I’d photograph kid stuff: my favorite things, best friend, stuffies, family. . . . The camera had a square format, which I’d tilt sideways so the frame was in the shape of a diamond to show how special the subject was to me.

The first picture I made that taught me photography could go beyond the literal was of a storm rolling into the horizon at our farm. I remember the thrill at seeing the print, how the photo captured that feeling of excitement and exhilaration of wind picking up and the sky darkening.

Thinking back to your first arrival in Wisconsin back in 2014, how were you received by the people in these towns? The kinds of portraits you made require willing collaborators, so you must have developed strong trust and rapport within the communities you visited.

Wisconsinites are very proud of their state and their way of life, so, from the start, people were very welcoming and thought it perfectly natural that I’d take an interest. I began photographing in schools, nursing homes, farms, police stations, churches, and at community events. Through these encounters, I developed more personal relationships with people and was invited into more intimate settings.

How did you gain access to spaces that are normally quite private, like schools, nursing homes, and even police stations?

The project began with the support of the Milwaukee Art Museum. Before my first visit, when I started contacting schools and other organizations, being able to provide the museum’s formal letter of support opened many doors.

Once there, I developed relationships and friendships that led to others and have outlasted the project.

Through these relationships, you were invited into the most personal of spaces – people’s homes. Did you feel a greater responsibility in these contexts, to how you were depicting these subjects and spaces in the work?

I always feel a great sense of responsibility when photographing other people’s lives, be it strangers or family. In working on the final edit of a project, both the way someone is depicted and the context of their image are big considerations that determine my choices.

There were quite a few images I was attached to in this project, but ultimately decided against in the final edit of Some Say Ice. I felt the subjects were overly reinterpreted and I’d not left enough space for them, or I saw that without the whole backstory, which the viewer would not have, the image could be misconstrued.

Even being as careful as you can, there’s always a chance someone will not agree with how they are presented, and it can hurt. But that’s a risk we all take when putting things out in the world.

Looking at all of the project’s portraits, I immediately noticed you capture people with deadpan expressions, never smiling or outwardly emoting. Why was it important to present your subjects devoid of emotion?

When you’re by yourself, you usually are not smiling or making facial expressions. It doesn’t mean you’re devoid of emotions – quite the opposite. You’re just not displaying them.

To encourage people to be more present in that way, I worked with my small camera as if it were large format. I used a tripod and slow shutter speeds to make everyone slow down and create a more ritual-like mood.

Why was it important to you that your subjects be “present in that way”? Is that something you think about in all projects, or were you specifically attuned to it in this body of work?

That all of the portraits are done this way is probably more specific to this project. But I usually do tend to slow things down when making portraits, so that people can settle in and be present.

In addition to the absence of facial expressions, I was struck by the sense of timelessness that pervades the project. Despite some contemporary markers of time, it feels like many of these pictures could easily have been made 50 years ago. Can you talk about that a bit?

It wasn’t so much about making the photographs look timeless as it was austere. I avoided obvious signs of contemporary life, like cell phones, televisions, advertisements, and fashion, which are inconsequential at the end of the day.

Was it difficult to avoid signs the contemporary? Or did you feel like austerity speaks to the character of life in these towns?

Hmmm. . . . no, it was pretty organic to what it felt like. There was something there that spoke to me in the sincerity of both the people and lived spaces – unaffected, with no more than what is needed and loved.

The number of references to Christianity – both overt and subtle – suggest that religion is of great importance, counted by many as something that is needed and loved. How prominently does religion shape the communities you visited?

In the rural areas I visited, religion is central to most people’s lives and identities, and churches are hubs that build and hold communities together. I became good friends with the Reverend of a small storybook-like chapel in Black River Falls who holds the warmest and most joyful services I’ve ever attended. You can take your dog, dress as you like, and never feel judged.

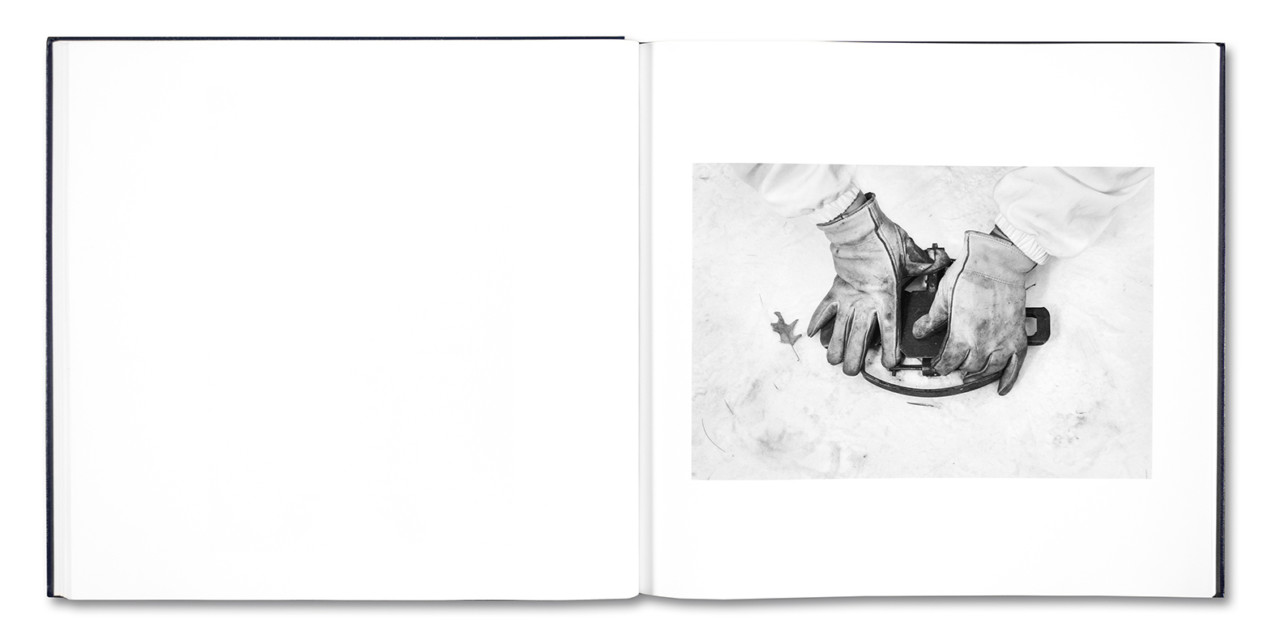

Animals – both domesticated and wild, alive and dead – also appear throughout. What do they signify in this project?

To me, animals are the purest constant in this world. That’s why, throughout history, we have endowed them with so much symbolism. They are silent witnesses to all of humanity’s absurdities.

They’re also central to Wisconsin life – for companionship, sustenance, or entertainment. Dairy farming and all kinds of hunting – deer, coyote, duck, crow, bear – are a main part of life there.

You photographed over an eight-year period, spanning a time of tremendous economic, political, and social change in the United States. How did you see that change and upheaval reflected in these midwestern towns?

After 2016, when the darker undercurrent of the US came to the surface, the beliefs and attitudes I had dismissed as quirks or cultural differences became heavier and more threatening, so they were certainly on my mind. I went into the work with many fixed ideas about the Midwest and left humbled, with many more questions than answers.

Perhaps the light in many of these pictures, which is particularly theatrical and portentous, speaks indirectly to the kind of heaviness you sensed. Can you talk about the quality of light in this project? What do you hope it communicates?

Most of the work was made in deep winter, when the days are short, dark, and somewhat claustrophobic. The lighting was meant to both capture the feeling of sheltering from the cold and dark, and convey that light isn’t a given. We could be in the dark at any moment.

I’d like to hear about your approach to editing and sequencing Some Say Ice. Did the unique structure of Wisconsin Death Trip impact your process?

Wisconsin Death Trip motivated me to work in Black River Falls, but it was not the model for sequencing or editing.

What kinds of concerns did guide the development of your book’s final sequence?

I intended for the book to feel more like a riddle than a statement about a place. That was the guiding principle. Unlike The Adventures of Guille and Belinda [first published by Nazraeli Press in 2010, then reprinted by Mack in 2020], this story has no chronology or linear narrative, only the trajectory towards the inevitable.

How does it feel to have finished this book, representing the culmination of nearly a decade thinking about and working on this project?

I have a real sense of closure publishing this work. Like something came full circle and now I’m free to move on in any direction.

In a short statement at the end of the book, you mention photographing as a means of keeping everything and everyone around you from disappearing. Has that impacted the way you continue to document your own life and family?

I used to photograph 24/7 at home, but not anymore. It distances me from my family and fills the moment with melancholy.

I used to photograph my daughter all the time until she hit her teens. Then, she asked me to stop, saying it ruined the moment and made everything seem less real. Now, I mostly stick to cell phone pictures when it comes to friends and family.