Alex Majoli on Mentoring and the Power of Dialogue

Ahead of a long-term mentoring program with Gilles Peress, Alex Majoli shares his thoughts on photographic mentoring and the role of dialogue: “Photography is not about taking images only".

When Alex Majoli and Gilles Peress lead a six-month mentorship program in January, they will be asking participants lots of questions and leading probing discussions. They won’t be offering photo assignments. Their goal is to help the participants pursue long-term personal projects. To help them develop their own distinctive visual language. Majoli and Peress are planning exercises to encourage the participants to discuss “what they read, what they think, and what they do all day,” Majoli says. As he puts it, “Photography is not about taking images only.”

Majoli developed his ideas about teaching after leading short-term photo workshops. “Taking pictures for a week doesn’t help at all,” he says. “You leave with a nice portfolio, but then on Monday, when you’re back home, nothing has changed.” Or, after studying with a master photographer, he says, “Their work looks exactly like that of the master. They didn’t learn anything.”

Majoli restructured his classes to encourage students to talk about their photography before making photos. “I try to create a foundation where everybody can start again and rethink their own photography and how they want to do it—not how I would do it.” He also spends time listening to students and helping them refine their ideas. “Dialogue is really crucial. In dialogue, we find truths.” In one-on-one conversations with Majoli, his students “really opened up” to him about their lives, what they cared about, and why. Photographers who have worked with Majoli, including Olga Bushkova, Valerio Spada and Piergiorgio Casotti, have gone on to pursue deeply personal projects they turned into books and films. Using a range of aesthetic styles, formats and media, the projects are as individual as the photographers who made them, and nothing like Majoli’s work.

"Dialogue is really crucial. In dialogue, we find truths."

- Alex Majoli

Majoli hopes that, at the end of the six month mentorship, the participants will have produced a book dummy they can develop in the future. He and Peress will also be joined by guest speakers who will offer feedback and suggestions of how the projects can best be presented and shared.

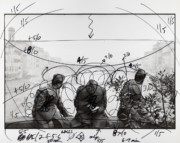

About his fellow mentor, Majoli says, “There are many great colleagues that take incredible images. In the case of Gilles, he taught me to look beyond the simple making of images.” Peress is renowned for innovating novel visual vocabularies that are consonant with both his subjects and his response to what he has witnessed. In his landmark book Telex Iran, for example, his startling compositions, tilted horizons, and bodies cut off by the image frame convey many things at once: the turmoil and uncertainty he observed in Iran after the revolution; his uncertainty; the ambiguity of his position as an outsider. In later works about the aftermath of ethnic cleansing in Rwanda, the Balkans and elsewhere, Peress’s compositions were often squarely framed. Their simplicity forces the viewer to look straight at the forensic evidence of horror.

Like Peress, Majoli has continued to reevaluate how photography functions. He was just a few years out of art school when he made the raw, emotional images in his first book Leros, about the closing of a brutal insane asylum in Greece. His new book, Scene, is a collection of photos he made over six years on four continents. Cinematic, ominous and often cloaked in shadow, the images explore Majoli’s sense of the theatricality and drama of everyday life.

Majoli’s books are the product of careful thought and editing, but in the moment of making photos, he works on instinct. “I photograph mostly with the stomach,” he says. He compares his way of making photos to diving into the crowd on a dance floor, and moving to whatever music is played. Once he begins sifting through the images he has made, he switches to a different way of working. “I use the brain and try to think about why I did that.” In his editing, he says he wants to “shape what was a pure instinct into something a little more sophisticated.”

Deciding what to photograph or which pictures to include or remove is complicated, he says, because we are so influenced by the images that bombard us daily. “You see something you’ve seen before – you don’t remember where – and you shoot that picture because it’s something you already have in your system. That doesn’t mean it belongs to you,” Majoli says.

He often tries to demolish certain myths about photography, and encourages students to re-examine their notions of how a photograph is supposed to look. He has shown his classes Renaissance paintings that influenced Western depictions of perspective, and iconic photos that echoed famous paintings from the history of art. “I always say that in National Geographic from the 1970s to 2000, you’ll never see any person from 11am to 4pm, because the light is not necessarily as amazing as it is at 6pm or 6am.” The photos produced within these boundaries are picturesque, but Majoli notes, “We had a gap in understanding what’s going in the world at those times for many years.”

Photographers will not come out of mentorship with a portfolio to show a photo editor, “in order to say, ‘Me too, I can do that,’” he says. His goal is for participants to make the stories they want to make, in what Majoli calls “their personal alphabet.” Majoli acknowledges that sometimes “desperation” forces photographers to retreat from experimentation. But as a mentor and a listener, he hopes to encourage others to persevere on their own path. “I understand that it’s difficult to live this life as a photographer,” he says. “But sometimes you have to resist and believe in your work, and eventually it’ll happen.”

To find out more about the Long Term Mentorship opportunity with Alex and Gilles, click here.