Back to the Archive, Looking for Peace with Newsha Tavakolian

Newsha Tavakolian speaks to Sara Kazemimanesh from her studio in Teheran about the series “And They Laughed at Me”

Magnum photographer Newsha Tavakolian speaks to me from her studio in northwestern Tehran: a repurposed common room in the basement of the residential complex where she used to live. While I am unable to interview her in person, I have no trouble imagining myself walking down the stairs to sit at the red table in the center. We speak in Farsi, our native language, as she makes coffee at her makeshift coffee station in the corner before joining me for our chat.

Floor-to-ceiling windows on one side let the daylight in and are sometimes rattled by powerful gusts of wind. A little imperfect glass jar with frequent visits from curious neighborhood cats and other residents who occasionally take a moment to peek through the tinted glass. She is admittedly “a very private person,” but she chooses to keep her studio open with the blinds up, like a ship in the dark: “I want people to see that the light is on and there is someone here, working; life goes on.”

Our conversation revolves around her recent solo exhibition as the first recipient of the newly established Deloitte Photo Grant. In And They Laughed at Me, which opened on December 13 in Milan at the Museo delle Culture, Tavakolian critically examines a collection of photographs that she took during the first three years of her career, from 1996 to 1999. However, the project is a significant diversion from her technically meticulous approach to image selection, as she has only included photos that are flawed in some way. In stark contrast to the high-resolution crisp photographs that she normally produces, these images contain “mistakes” made by her, her subjects, photo lab technicians, and her camera. Overexposed scenes, wayward frames, and blinking subjects have compiled into a once obscure treasure that she has now recovered from her archive.

It is a full-circle moment in her career, as her initiation into the world of professional photography was through the archive. As a teenage high school dropout, Tavakolian’s inquisitive mind propelled her into an extremely volatile and ruthless world of politics, as the formative years of her career coincided with popular reformist president Khatami’s election into office. His two consecutive terms in office were marked by relative openness in the cultural sphere of Iran, a bright prospect for the millions of post-revolution baby boomers like Tavakolian herself. However, the collective surge in hopefulness was not all that she experienced during this time, as waves of political conflict, the undue crackdown of student protests, and the shutting down of newspapers — including the Zan daily paper where she worked — complicated her perspective. “I grew up quicker than others, but I refused to let my work be used for any political agenda.”

"I was an aspiring amateur photographer; this skinny 16-year-old girl whom nobody knew."

-

She started to work in the archive at Zan (meaning woman in Farsi) newspaper just around the time when its first issue was about to come out. Her job was mostly clerical: “I’d be at the bureau at 9 in the morning. The first staff photographer would normally be back from their assignment by 10:30, 11. I’d then splice the negatives, write down the date and name of the photographer before filing them away. I was an aspiring amateur photographer; this skinny 16-year-old girl whom nobody knew.” Yet, she had an iron will to burrow into a complex professional world that offered no buffering zone where someone in her position could acclimate to the way things work.

“I remember the editor-in-chief rushed into the media room looking for a staff photographer to take the front-page photograph. But they were all out on assignments. I always had my camera on me, so naturally I volunteered and was overjoyed when she said that it didn’t matter who took the picture. I stopped by at home to grab some clothes and borrowed a few folk costumes from my friends, quickly making it back to the bureau. I had all the girls get ready, sat them down on the stairway holding up our first issue, and took the picture.” She tells me that after printing the photograph, she stayed in the editing room until the early hours of the next morning to make sure her name would be printed along with it. “And when I did go home, a combination of worry and thrill kept me awake all night.” Early the next morning, she went up to a kiosk and bought the paper. She sat down on a bench in a neighborhood park: “I stared at the front page for hours.”

When I ask her what she felt at that moment, she explains: “I felt contrasting waves of joy for having a dream realized, and guilt for not feeling content with it. I wanted more. But I knew that I had to return to working at the archive.” Back at the bureau, everyone had gathered to celebrate the publication of the first issue: “When I went down to the front yard, a few heads turned, and I got some looks. The staff photographers were upset that I had taken the front-page photo for the first issue. I explained that I took it because nobody was there but me. And that seemed like a good enough reason to settle the matter.”

Now in And They Laughed at Me, Tavakolian has returned to the archive, albeit this time taking a moment to ruminate on her own work. But this is not the first time she has felt obligated to pause and reconsider how to move forward professionally. More than a decade ago, her career as a prolific photojournalist was disrupted when she was temporarily banned from working in Iran. Back then, after taking some time off, she decided to embrace that obligatory change and made a conscious shift toward social documentary and conceptually creative work. “I always had social concerns. I wanted to be able to do meaningful work,” she explains. It was an enterprising move that would open new horizons for her, leading her on a transformative journey through which she became an auteur photographer.

"I have always struggled to understand why I have such a complicated way of seeing things."

-

Despite her globally extensive field work, she remains tethered to her homeland of Iran. Having witnessed multiple spectacles of widespread and violent social unrest in the country, and during the most recent wave of protests, she was faced with a new challenge. “I have always struggled to understand why I have such a complicated way of seeing things.” She goes on to tell me that she has often wondered if she would have found more joy in her work had she developed as an artist in a different environment. “But as I contemplated my earlier work, I realized that I have recurrently captured hope amassed into a collective will to change, only for that will to shatter and be replaced by a paralyzing sense of despair.” So, this time, feeling unmotivated to pick up her camera, she decided to examine her own gaze and the memories that shaped her. It was time for a perspective shift: “I felt a need to shed my skin and defy the urge to constantly create work in reaction.”

At a time when the world is governed by the production and fabrication of images, the act of revisiting old images is thought-provoking. She believes that it should be a doable challenge “to make people think while uplifting them and making them aware of their own power.”

In And They Laughed at Me, Tavakolian’s treatment of the images is notedly different from her previous projects. This is not solely because of the so-called subpar technical quality of the images: “This is the first time I’m using chemical processing creatively with the result completely out of my control.” However, she is no stranger to creative experimentation. In her directorial debut, a short film called For the Sake of Calmness, she experimented both with sound and image: the use of super slow-motion sequences maintained the sense of stillness of singular photographs, while revealing more motion than a single frame may offer. Already disillusioned by the world of politics, she tells me that during the production of For the Sake of Calmness, she experienced “a sense of exhaustion.” At the time, the unexpected passing of her father, one of her biggest supporters, was a significant catalyst for her changing perspective. The film marks the stirrings of a second intentional shift in Tavakolian’s career, which has come to fruition in And They Laughed at Me.

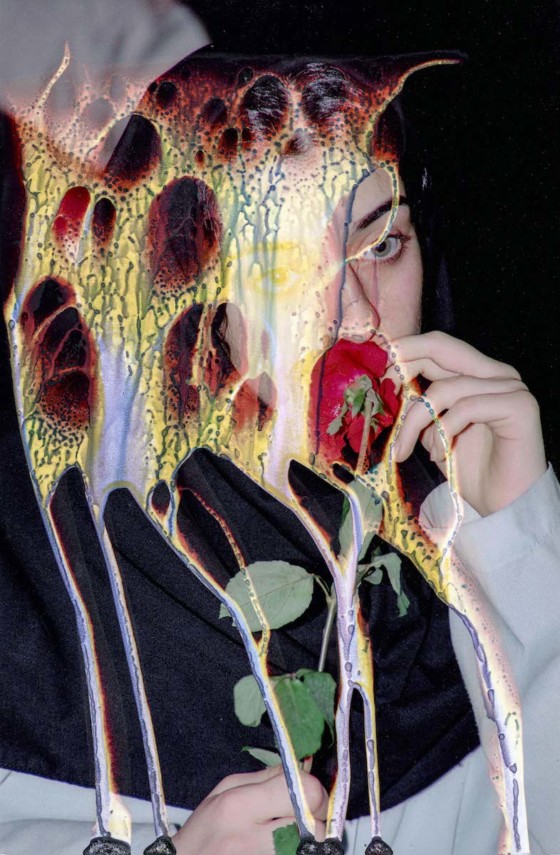

Within the raw compilation of her old images, we arrive at the pensive portrait of a young girl taking in the scent of a red rose. Matted black hair beneath a dark scarf, bright eyes with a distant look, slim fingers loosely wrapped around the stem: a moment of pause in an otherwise explosive historical era. It is as if the collection of images unfolds like a reel of film, revealing an overwhelming succession of visual cues. Each time the image appears, altered as it may be, it is as if time slows for a moment, urging us — the viewers — to do a double take. Did I not just see her? And perhaps, it also prompts us to go back and look at how different she looked the last time we saw her. This metaphorical traversing between the past and present corresponds to the way Tavakolian’s gaze has gradually shifted away from external observation, and toward self-reflection. It raises questions about the moment the photograph was taken, the girl herself, and her distant gaze as she smells the wilting rose.

"The female awakening that many have witnessed in Iran in the past year didn’t happen overnight. It has been ongoing for years."

-

Over 20 years ago, before the era of citizen journalism, Tavakolian took a picture of a female protester climbing a fence. To her, witnessing the way that girl determinedly hoisted herself up for a better vantage point was moving: “on stage or TV, we were used to seeing women acting subdued. They weren’t supposed to raise their arms above their shoulders per censorship laws.” She explains that her being there to document that young protester’s “fight for more” was serendipitous. But there were many others before her, who fought hard in their own way, with no cameras around to capture their efforts.

“The female awakening that many have witnessed in Iran in the past year didn’t happen overnight. It has been ongoing for years.” But people are seeing it now, because it is associated with an image-based spectacle that keeps regenerating itself. “I have grown to become quite cautious about being reactive because it interferes with the ability to digest important events.” She explains that when one is immersed in an experience that warrants kneejerk emotional responses, “it gets tough to stick to a conscious decision not to allow those reflexes to cloud your judgment.” But it is important that we try, because artists have a social responsibility to hold politicians accountable: “[politicians] should be aware of the eyes trained on them, and that their decisions will affect collectives of people.”

While she continues her practice as an artist and documentary photographer, Tavakolian dedicates half of her time to teaching: “Learning has always been difficult for me. So, I’d like to make it easier for others. Sometimes a little tip can help you take a leap forward.” In a contemporary world with rapidly mutating values, she finds working with the younger generation of photographers inspiring: “It helps me understand changing perspectives and keep my work relevant.”

To Tavakolian, the gradual abstraction of the portrait of the young girl represents a state of reset: a point of origin that enables her to curate new narratives. And while she is embracing this state of reset, she prepares for another chapter in her creative career. “I remain committed to challenging myself every few years,” she says before revealing that her most recent challenge is a feature film: “I have been developing a narrative script, which I hope to direct eventually.” She does not reveal much about the project. But considering her repertoire as a compelling visual narrator, it is worth the wait to see where this new path may lead her.

Girl Smelling Rose, an image from this series, will be available as an exclusive, hand-finished five-image portrait from Tavakolian as part of the new Limited Drop series of posters and prints. The sale runs from Friday, July 26 for 72 hours only. Find out more and sign up for early access here.

Words by Sara Kazemimanesh (@sarakazemimanesh)

Photographs of Tavakolian in her studio by Sina Shiri (@sinashirii)