Behind Bruce Gilden’s Portraits

The photographer shares a selection of color portraits from his archive and the story behind how, and why, he shoots them.

“You can’t define what a perfect portrait looks like. You know it when you see it.” Gilden explains to Martin Parr in front of a crowded Silencio in Paris one evening in November 2023. “I’ve learned so much by doing portraits,” he continues. “I can look at every person in this room and tell you who I could do a good portrait of and the ones that I can’t. I’ve learned the shape of the face, how deep the eyes are set… I’m always learning.”

Now, Gilden has made a selection of 10 color portraits from his archive. Half are from the photographer’s well-known projects from the past decade. We see the familiar face of Jenna from Farm Boys and Farm Girls USA (2017), a series documenting youth at Middle America’s state fairs, or Bonnie and her kitten, who appeared in Face, published in 2015 by Dewi Lewis. Another shows a portrait of a woman with the nickname “Texas,” from Miami, the clashing colors of the blue and yellow wall serving as a backdrop to her tough, confident posture and heavily made-up eyes. “Texas” is one of the women from Only God Can Judge Me, a poignant project on “drug-addicted prostitutes” that Gilden conducted from 2016 to 2019 (published in 2018 by Brown’s Editions of London).

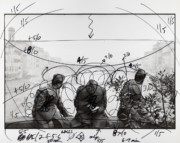

The other half are new portraits from ongoing projects, made over the past 12 months in the United States and Mexico. Each portrait is unashamedly Gilden: a close-up of the face alone, or from the waist-up, always with flash. They are direct, jarring. His style of portraiture has once been described as ‘unforgiving.’

Shooting collaborative portraits in color was a huge shift for Gilden in his nearly-60-year old career, having grown to fame with his black-and-white, gritty street photographs of New York City, Haiti, and then Japan. His color portraits are carefully crafted, with the photographer spending time with each person and attempting to capture what initially caught his eye about them. “I was at the Minnesota State Fair one day and there were over 200,000 people there,” he explains to Parr during the talk. “I mean it was packed but I only made five portraits that day. I’m very selective.”

“Would you be able to define what is in a person’s face that makes you want to take that picture?” Parr asks. “I can,” Gilden replies. “It’s when they have an interesting roadmap. They have intense eyes. Every once in a while, very rarely, you see a person and you think, wow! — I hope they say yes to the portrait. Because you know you have the picture.”

“Do you show them the portrait?” Parr continues. “If they ask,” Gilden responds. “And what do they say when they see them?”

“It depends who you ask. People have preconceived ideas about how the persons I photograph must react when they see the portrait I took of them. They think that the ones that wouldn’t be defined in our society as ‘beautiful,’ would be the most critical. That’s not the case.”

“Stern once hired me to make a portrait of a famous director and I only had about ten minutes to do it. We were on Houston Street and we did a very basic portrait because if you’re a pro and you don’t have much time, you’ve got to make sure you get ‘the shot.’ It wasn’t even with flash. A week later, I get a call from my agent saying that the director didn’t like the portrait: his nose looked too big…

“Then, there was this lady in the West Midlands who had seen better days. She had lipstick over her face and was missing her teeth, and when I asked if I could take her picture, she said yes. After I took it she asked to see it so I showed her and I said what do you think? She answered ‘I’m beautiful.’”

“What people don’t realize is that society doesn’t pay attention to these people. When I started Faces, I thought most of these people were left behind, but actually most of them are completely invisible. People don’t care about them.

“One very strong portrait that I did is of a guy that I also met in the Midlands. We talked for 20 minutes and then I took his picture and I just felt that he would then go back to his room, watch his black and white television, sad and so lonely. It affected me. I can understand if someone doesn’t want to put his portrait on their wall, but it’s a statement, a strong picture about life. I mean the world isn’t wonderful, look what goes on all the time. My pictures are real. That’s it.”

One image from Gilden’s selection is a portrait of Frieda that he took on one of the several trips that he made to Mexico in 2023. In an interview about the image selection, he shares the story behind the image: “She agreed to do a portrait so we took a first picture, but the background wasn’t right. I walked away but wasn’t happy with the picture, so I went back and eventually found her again, asking if we could walk three or four blocks until we found the right background. I knew exactly what I was looking for, I knew I wanted a cigarette in the mouth, but in a certain position, and the ash had to be a certain length.

She had had a really tough life. She told us about a lot of really bad situations where she found herself with drug cartels. You could see the trauma and loneliness in her face.”

Another very strong portrait taken on the street in Kensington, Philadelphia is of Amber, a young woman with eyebrows furrowed and her top lip slightly curled up into a scowl. She seems stern and confident. How did Gilden approach her? “When I have to go out and photograph I have to be in the mood to talk to people, and when you just arrive at a place that can be tough,” Gilden explains.

“When I first saw Amber I loved the tattoos on her face and I was intrigued. I started talking to another woman who knew her and she went to her and asked her permission to be photographed. Amber is tough, fierce and aggressive. It’s hard to describe, but I wouldn’t call her a victim despite her circumstances, she doesn’t act like one.

“My portraits are supposed to tell stories,” Gilden explains, ‘and stories of real life. We make many of our judgments based on what these people look like, not who they are, or what they have lived through.

“You can learn photography in college, or you can learn photography from life,” he continues. “I suffered emotionally, and it shows in these pictures. But if you don’t look at reality face to face, how do you change it?”

In Face, Gilden draws upon a quote from Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray in the book’s afterword: “Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter.” If this is the case, then, what are Gilden’s portraits trying to tell us? Are they a reflection of Gilden’s life and tough upbringing? Or are they, in their unapologetic directness, a call to look, to take note, and not simply turn away?

Watch the full discussion between Bruce Gilden and Martin Parr here.