Bit by Bit, Mikhael Subotzky’s Destructive Collage Process Dismantles Depictions of White “Founding Fathers”

The photographer discusses his creative process and the importance of breaking historical cycles of racism, violence, and oppression

Magnum Live Labs offer a space for experimentation, making visible the collaborative process of creating new work. Participating photographers, working alongside a local curator, are challenged to respond to the location of each lab, making, editing and exhibiting new works together.

This year’s partnership with The High Museum of Art and The Hagan Family Foundation in Atlanta, was to be the first Lab hosted in an institutional space. Mikhael Subotzky, Carolyn Drake and Lindokuhle Sobekwa’s work represents the most diverse group of practices from Magnum to date, encompassing mixed media arts alongside photography. With the physical residency halted by COVID-19, the creative thinking went on.

This piece is part of a series of posts co-published with The High Museum of Art in Atlanta. Read an introduction by the museum’s Associate Curator of Photography, Gregory Harris, to the Magnum Live Lab program, here. Read the first of the interviews with the three photographers in the series, a Q&A with Drake, here. Last week’s interview with Sobekwa can be read here.

In this – the last interview of the series – Gregory Harris speaks with Subotzky about confronting his ‘privilege and complicitness’, and his creative processes.

On June 18 Harris and the photographers will hold a live conversation on Zoom at 12 noon.

What was your perception of Atlanta as you were preparing for the Live Lab?

I didn’t have a strong one, to be honest, just the usual cursory impression of MLK and civil rights history. And CNN. But I knew of the High and its incredible program and collection for quite some time too.

What were you originally planning to work on during the residency? How did you select the focus of your work during Live Lab?

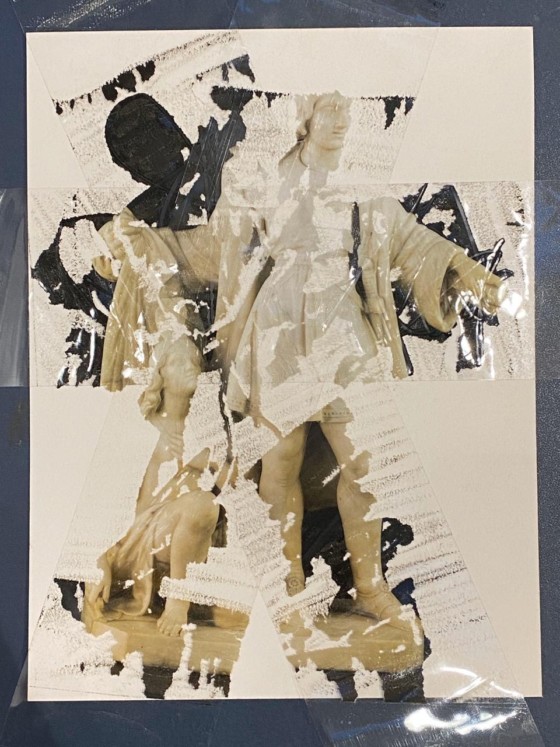

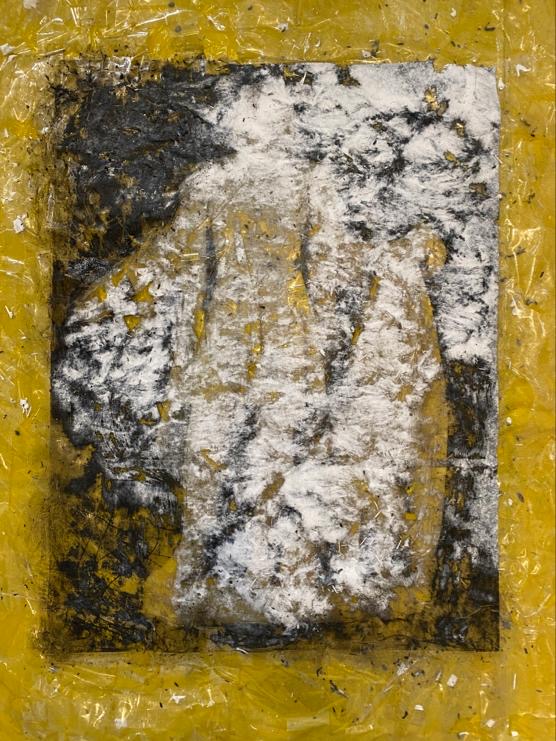

My plan was to work on two projects. Firstly, I was going to carry on making works from my Gangster Series. This series of works examines various figures in Western history whose mythologized presence is deconstructed and disassembled through the sticky-tape process. Each portrait is treated to a smothering layer of tape; then the image is dissolved and picked away, revealing a degrading core.

It’s an attack on the history of portraiture as much as on the figures depicted, an attempt to make them appear far less comfortable in their poses of power. There are a number of candidates for the “gangster treatment” in the High’s collection.

Secondly, I was going to continue with a new long-term film project, entitled Disordered, and Flatulent: A Work In Progress. This is an animated film that is related to the Gangsters — a look at the transmission of both generational wealth and cycles of violence. The parallels between American and South African history, politics, social dynamics, and general state of mind are always so strong.

You were here in the US for a few days before returning home to quarantine. What did you do while you were here?

I passed through New York to see some friends, look at some art, and go to a few meetings. Then I went up to Boston to do some research at MIT Media Lab for a project on the relationship between the brain and the gut, which we are all learning are much more connected than commonly understood. I was about to fly from there to Atlanta when things shut down and I had to rush to get home.

When you returned home, you and Lindo went into quarantine in your home. What was that experience like? Did you continue to work? What kinds of conversations were you having?

Our conversations were limited by the fact that we were both having to self-isolate, and my wife was also in the house. But we started taking walks together, and that was great — a chance to talk about photography and our surroundings, and I particularly enjoyed watching Lindo work, giving him a few tips, and of course learning from him too.

Amid quarantine, how have you adjusted the work you’re doing? Upon returning home, did you carry through with any of your initial plans for the Live Lab? Earlier in your career you worked in a more traditional “documentary” mode. These days you rarely use a camera to make images. What caused you to shift away from making photographs?

As South Africa entered lockdown and Lindo returned home to his family after quarantine, I turned the spare room in my house where Lindo had been staying into a mini studio, seeing as I couldn’t travel to my main studio. This is pretty much what I was planning on doing in the Live Lab space at the High, so quite comfortable, in fact.

The second part of the question would take a long time to answer, but I do still use a camera to make images, just in a different way. I have always used image making to try to understand the world and my place in it; it is simply that the camera has been replaced with a broader variety of image-making tools and no longer holds a privileged spot in my practice.

You work with a unique collage process. Can you tell us about it and how you developed this way of working?

Yeah, I call these works Sticky-tape Transfers. They are derived from a wide variety of sources — scanned images from the artist’s book collection, sketches I’ve made over the years, photographs I’ve taken, images from my personal history, photography guide books, encyclopedias, etc.

The process of making these works is normally to scan and make inkjet prints of the source images and then work them together in collage, often combining them with censoring white-out tape and handwritten text excerpts. I then lay the pieces on the studio floor and cover their entire surface with J-Lar tape, a highly stable archival clear tape.

Once this is done, I pull the tape away from prints, separating the ink of the prints (as well as anything that has been added to their surfaces) from their paper supports. Or I use a more delicate process — weaving together images strip by strip.

Sometimes I draw on the lightly applied tape to remove it selectively; sometimes I scrub at the back of the tape to remove parts of the transferred ink.

What drew you to the image of the Edmonia Lewis sculpture from the High’s collection, and why did you want to apply this process to that image? Tell us about your decision to work on the piece even though you weren’t able to make it to the High.

It’s such a fascinating image, and Columbus, of course, is one of history’s most prominent gangsters. It just felt like the perfect image to connect the work I was doing anyway in South Africa with a parallel history in the US, and Atlanta in particular.

Once my mind was there and all the materials had been prepared, it just made sense to carry on with it here in Joburg.

For a while now, you’ve been working on a body of work that critically considers depictions of “founding fathers” in Western art history. Can you tell us about this project and why you wanted to continue working on it in Atlanta?

Yes, it’s been a while, but my thoughts on this project are still not fully formed.

It starts in 1632 when Rembrandt was paid to paint a bunch of white men in a semi-circle around the pale, prone corpse of Adriaan Adriaanszoon. In 1652, Jan van Riebeeck, a corrupt mid-level manager at a multinational corporation, arrived at the Cape of Good Hope [in what is now South Africa] and stole the land next to the Camissa River from the Goringhaicona.

And on the 28th of September 1654, John Milton wrote a desperate plea to his doctor Leonard Philaras as he sunk into blindness while preparing to compose Paradise Lost, a foundational text in our conception of Western thought. He writes: “I think it is about ten years since I first perceived my sight to weaken and become dull: at the same time my spleen and bowels were disordered, and flatulent . . .” Paradise Lost is a story of both morality and doubt, a series of inner conflicts described by God and Satan, and the author himself, grappling with both his power and his uncertainty.

Something was up, and it wasn’t the fortunes of the millions of slaves who were violently coerced to sacrifice their lives and bodies to build the “Golden Age.” None of the ships that transported slaves and built the Dutch and British Empires could have been made without Baltic timber, and it is not hard to imagine my ancestors in Lithuania felling trees or trading in their trunks, a couple of hundred years before they followed the wood south. I feel connected to this time period in ways that are both prosaic while at the same time deeply profound, personally and culturally.

The work I’m busy with now, Disordered, and Flatulent: A Work In Progress, takes on these ideas, examining the inheritance of wealth and woes; violence given and violence received; privilege and pain passed on from one generation to the next. And the conflict between hubris and uncertainty in the pale sickly men who shaped these histories, blinded by greed, lust, belief, and doubt.

The Live Lab was conceived to open up an artist’s creative process to a general audience. What do you hope people will take away from seeing how you work as an artist and how you’ve adapted your process to the new situation created by the coronavirus?

It’s not just coronavirus; since you sent these questions, the tragic murder of George Floyd has changed the world again.

It was thrilling to see the statue of Edward Colston thrown into the river in Bristol yesterday. And yet at the same time, both coronavirus and this latest wave of BLM protests have in many ways just emphasized what we knew already — that the world is a violent and unfair place for many, many people.

I hate this profoundly and at the same time need to acknowledge my privilege and complicitness. That is really what is behind my work at the moment. But that would have been anyway; it just carries on, on its own course, taking me with it.

The Live Lab Photography Residency and Exhibition are organized by the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, and Magnum Photos. This project is funded by the Hagan Foundations.