Breaking Out of the Archive Trap

New gazes and promoting diversity in curatorship can help redefine the role of the archive in contemporary society, as discussed by Mark Sealy and Diane Dufour

Archives are a document of history, but the version of history they promote is not challenged as much as some would argue it should be. American writer James Baldwin wrote in his essay Stranger in the Village that, “People are trapped in history, and history is trapped in them.” In it, the African-American novelist recounts the experience of being black in an all-white village in Switzerland in the early 1950s. While initially focused on his treatment by white villagers, the piece broadens to race in America, as he explores the dynamics of privilege and power, skewed and weighed down by the history of African diaspora. He questions whether James Joyce’s assertion in Ulysses that “history is a nightmare” is, in fact, a “nightmare from which no one can awaken.”

Archives capture history in so much as they enshrine the perspectives of those who have been privileged enough to tell it and record it, as exposed by Mark Sealy MBE and LE BAL director Diane Dufour at a recent talk. They argued that by taking into account diverse viewpoints, and broader, more inclusive curations, it is possible to re-assess the archive’s monolithic status, and break free from the trap of viewing archives as the single repositories of historical truth-telling, which Sealy argues has influenced not just the history of photography, but history itself.

Here, we present some points of consideration on rethinking, creating and exploring archives, as discussed by Sealy and Dufour at the Magnum Photos Now talk New Approaches to the Archive at the Barbican Center in London in June 2017. Presented here alongside images from the LE BAL exhibition, and some that were referenced in the discussion.

Media Influence in Biased Political Times

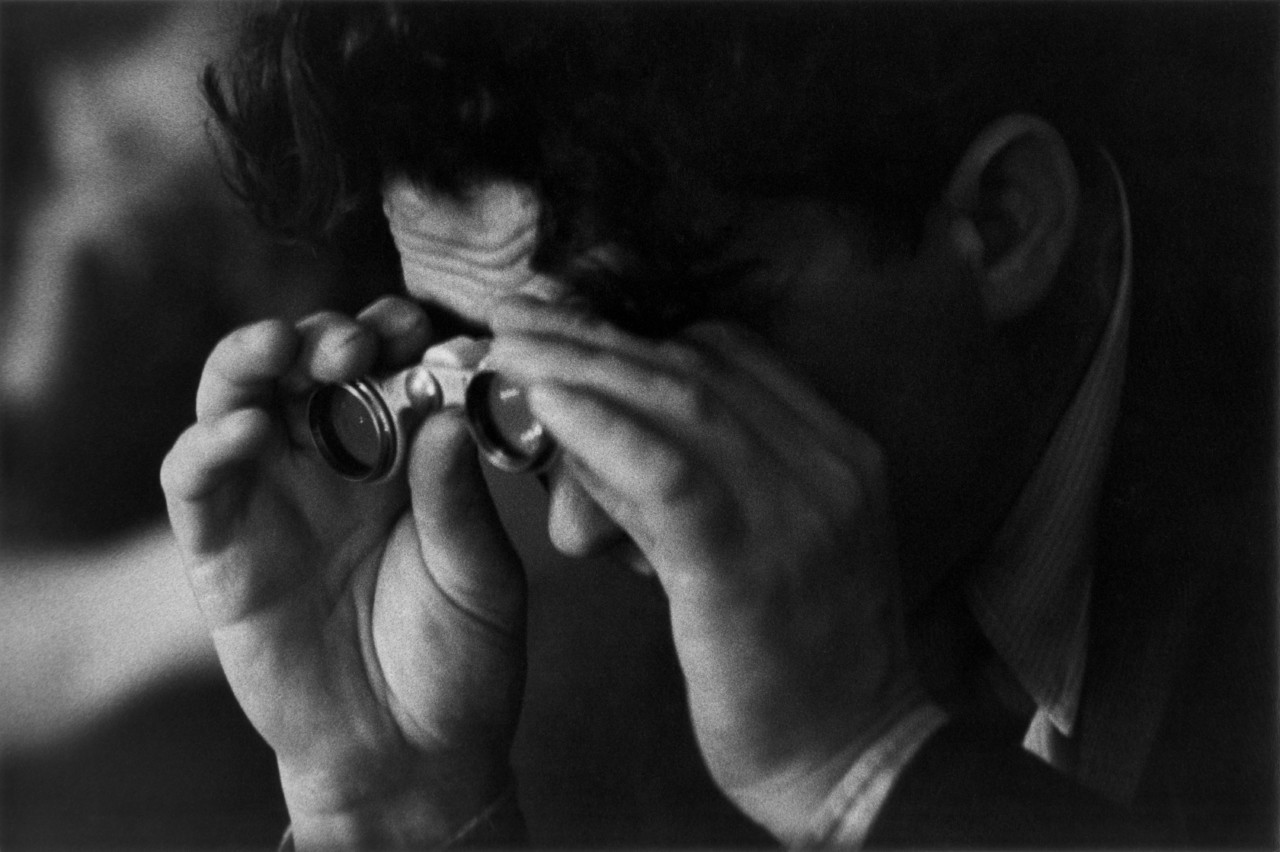

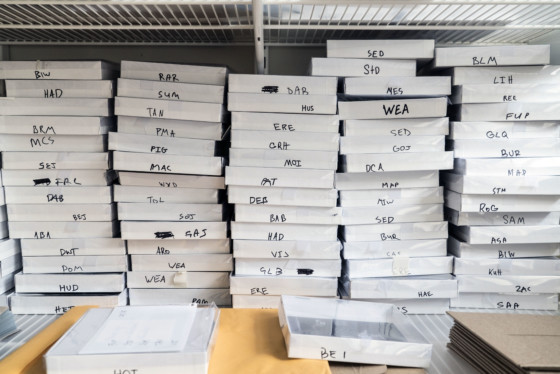

Through looking back at archived Magnum stories for the show Analog Recovery at LE BAL, the gallery’s director, and former director of Magnum Photos, Diane Dufour found insights into the photography practices at the time of the agency’s founding, when the main activity of the photographers was still commissioned stories from magazines (today they have a varied practice spanning self-funded work and personal projects, exhibitions, teaching, and more).

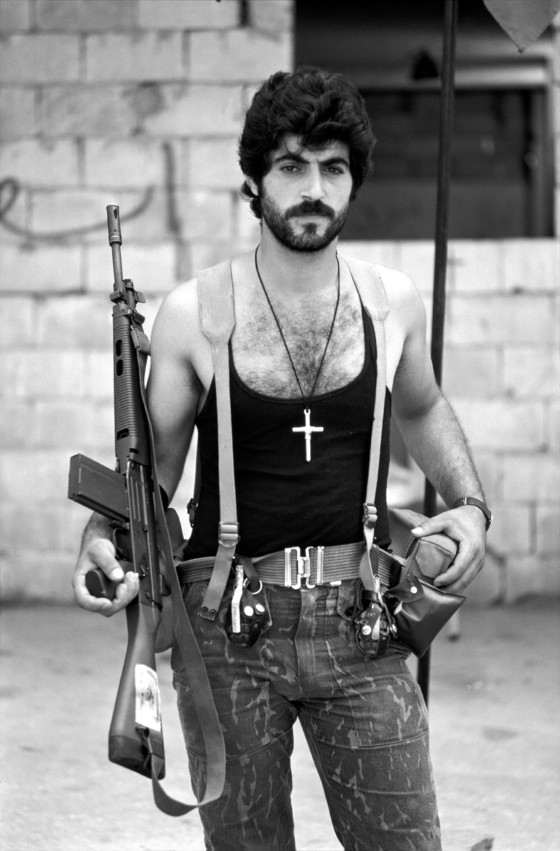

Magnum was set up to give photographers some control over of their work at a time when magazines usually retained the copyright of photographic assignments. “Capa, by creating Magnum, made a big gesture, turning the assigned photographer into an author,” she said. But while the photographers now had more control over what they shot and how, the magazines still controlled what made it into he public domain by making the call on what was published. For example, in the 1940s and 50s Robert Capa, David Seymour and George Rodger were all covering the Israeli-Arab war in Palestine. Capa and Seymour’s photographs of the Jewish refugee camps were published in the press, but Rodger’s images of Palestinians’ destroyed homes and villages were not. Rodger later wrote, “my versions of the facts were never published by magazines.”

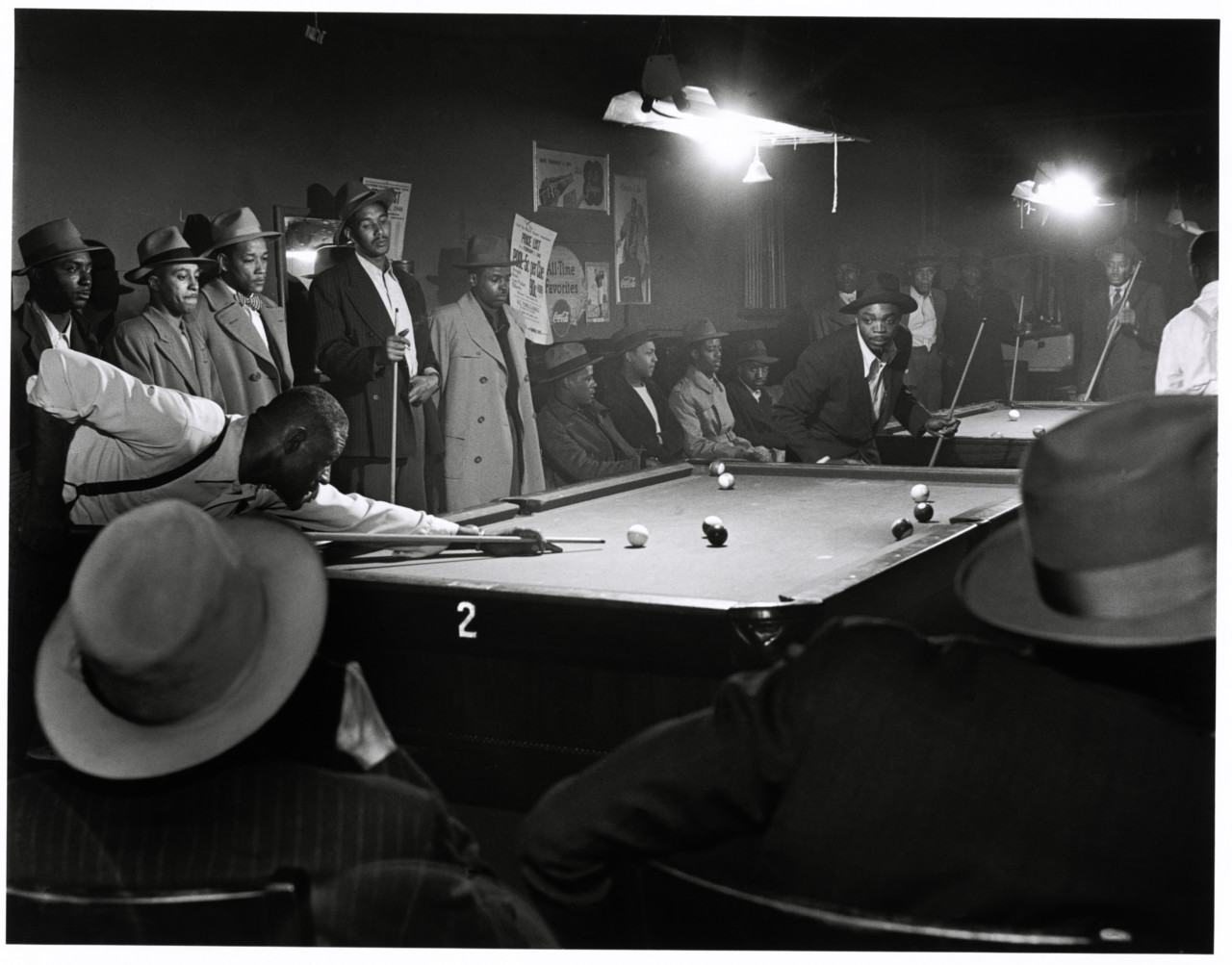

Mark Sealy’s exploration of the Magnum archives also found similar evidence of stories that had been photographed but not widely published until decades later. When he started to explore the representation of black subjects within Magnum under the auspices of his project Black Chronicles, he became fascinated with Wayne Miller’s Chicago work, for which the Magnum photographer was awarded two Guggenheim grants back-to-back.

"If we start to blend timelines through our work, we begin to see that we’ve always lived in these very biased political times"

- Mark Sealy

“What I found interesting is that after four years of photographing in Chicago back to back, there’s no visibility of the work. It kind of goes to sleep until the year 2002. What happened to Wayne’s work? And why is it nearly 50 years before these really interesting images of Chicago are allowed to emerge? These are probably the most important photographs of post-war black America in my view.”

“If we start to blend timelines through our work, we begin to see that we’ve always lived in these very biased political times and only when you begin to highlight that, can we begin to look at how contradictory our overall visual, cultural political world actually is,” said Sealy.

While the founding of Magnum allowed photographers freedom to cover wider perspectives on the stories of the day and to retain the copyright of their work, the fact that printed magazines were still the primary platform for the work was evident in most of the stories produced in the 50’s and strongly influenced the way in which the work was made. For example, the “New York Preacher” or “Long island migrants labor camps” stories by Eve Arnold exemplified “the idea of the picture story, providing an opening picture, a closing picture, which was very much in the process used by the illustrated press before the war.” Despite the freedom of authorship Magnum allowed, the medium the pictures would appear in still seemed to dictate the process of their creation.

Unlocking Ourselves

The medium of photography has a “devastating indexical nature… it may well have locked certain parts of the world, and various gendered types of peoples, in a frame which we cannot unlock ourselves from,” says Mark Sealy, echoing James Baldwin’s comments about history being “a nightmare from which no one can awaken.”

“We are permanently and perpetually fixed in this space because of this dark historical past, in these pseudo-sciences that unfortunately photography has become associated with” continues Sealy. He points to the work of contemporary artists whose work focuses on unlocking these spaces.

The black experience during the 1950s and 60s, according to photographic records, appears to be centered on political and civil rights movement; but the truth is, black life was fuller, more nuanced and, for many, less politicized than the narrow view provided by visual records of the time suggests. “The history of photography told us that there were no black photographers photographing in London during the 1960s,” said Sealy. “But meet James Barnor, who was here making fashion shoots for African people through Drum Magazine for consumption in Africa.”

The fashion shoot images were made in the same political context that images representing racial divides in society were made in; yet there is a dominant narrative that narrows our understanding of the full experience. Sealy wants to attempt to close these gaps in our understanding of history by re-assessing the way events are represented in photography. He promotes the creation of a more comprehensive archive, by making sure these moments are not isolated from each other. “In 1968-9, Britain was loaded with not just the civil rights movement. It was legislated that it was quite legal for you to advertise that you didn’t want a type of person living in your house or working in your factory. James’s photographs in Drum Magazine circulated across Africa and showed up in London, through the prism of these race acts that were still alive at the time.”

A more inclusive curation to write modern history

“We’re beginning to realize that the history of photography is nowhere near written. It’s so empty, so vacuous,” said Sealy. “There are huge gaps that need to be filled across various perspectives and people who have the camera.” The solution, he argues, lies in locating “our silent history”. “I think once we get ourselves over the idea that photography is not this fantastic invention and the eyes of the world, but is just another dominant tool, historically in the hands of many European narratives, then I think we’re in a place where we can begin to unpick its social meanings in a very different way,” he says. “It’s very simple curatorial work. It’s just about moving past the assumption that things aren’t always the way that our world tells us that they are.”

Who gets to build archives, whose work is included, and from whose perspective existing archives are explored dictate the document of history. So by taking into account a number of perspectives on a moment, a broader and more inclusive story begins to be told. This is why now, big efforts are being made to build archives of a more diverse history of Britain by acquiring vernacular work. This is work that, owing to the structures of power in society and the media, was most often independent, and not commissioned and remains unpublished.

“What we realize is that one of the key things that one has to do is recognise that of course peoples picked up cameras: Neil Kenlock Armet Francis and Charlie Phillips … And the reason why they picked up their cameras is not because they wanted to record the world, they’re not interested in that space. What they wanted to do is to make sure that their people were actually recorded. Never mind what’s going on in the global scheme of things. They’re absent from the field of representation,” said Sealy.

“My argument is this, in terms of considering their work: they may not be the best photographers in the world, but they certainly love their subject and without the care and commitment that they had for their subject, these images would never exist today. And now because the archive does its work and time does its work, they become inherently more interesting because we can begin to understand that there were moments like the black panthers in Britain.”

"We’re beginning to realize that the history of photography is nowhere near written"

- Mark Sealy

Youth and the loss of truth

As an educator, Diane Dufour and her peers are in regular contact with young people, and part of the program they teach includes visual literacy – understanding the ‘what, how, when and for who’ an image was taken. “This literacy which can help to build a critical eye from a very different perspective,” she said. But now teenagers are highly attuned to the potential for images to mislead: they see conflicting and confusing ‘fake news’ on social media, and are well-versed in using those platforms to create their own false reality, be it though highly filtered and deceptively curated Instagram feeds that create an impression of a life that is far removed from reality. Dufour is finding this is affecting their trust in images, and history overall.

"Now we are facing a situation where images totally lost their indexation towards reality"

- Diane Dufour

“Post the terrorist attacks in France, some teachers were facing a very difficult situation where what we call the post truth syndrome, where the history teacher said, ‘I’m going to teach the story about colonisation,’ And the 17-year-olds said, ‘No, what you’re telling us is not the truth.’ Then, they say, ‘We’re going to move to the Arab Spring, and we’re going to tell you what was going on in Egypt,’ And the kids said no this is your story, but this is not the truth.’”

“It’s extremely interesting because what we are facing is a kind of situation where some teenagers think in a different perspective, and bring an opposite perspective on images. They think that images can do everything. For example, you can build a family, a fake family, or you can make fake friends, or you can make a fake look, or a fake Saturday evening, to make a new story towards your friends. Now we are facing a situation where images totally lost their indexation towards reality.”

Read about more discussions from the Magnum Photos Now events here.