Carolyn Drake Explores Atlanta through the Lens of James Baldwin’s Writing on the Atlanta Child Murders

Researching, photographing, finding archival materials, and stitching the pieces together

Magnum Live Labs offer a space for experimentation and make visible the collaborative process of making new work. Participating photographers, working alongside a local curator, are challenged to respond to the location of each lab, making, editing and exhibiting new works together.

This year’s partnership with The High Museum of Art and The Hagan Family Foundation in Atlanta, was to be the first Lab hosted in an institutional space. Mikhael Subotzky, Carolyn Drake and Lindokuhle Sobekwa represent the most diverse group of Magnum practitioners to date, encompassing mixed media arts practice alongside photography. With the physical residency halted by COVI-19, the creative thinking went on.

This piece is part of a series of posts co-published with The High Museum of Art in Atlanta. Read an introduction by the museum’s Associate Curator of Photography, Gregory Harris, to the Magnum Live Lab program, here. In this interview, Gregory Harris and Eva Berlin, Digital Content Specialist, High Museum of Art, speak with Carolyn Drake about her ongoing work on the city.

On June 18 Harris and the photographers will hold a live conversation on Zoom at 12 noon.

Our first Q&A session is with Carolyn Drake, an artist who pursues long-term photo-based projects that focus on place and how individuals live and interact within inherent physical or societal boundaries. Read on for Carolyn’s insights, images of her in-progress work, and a video in her studio.

What was your perception of Atlanta as you were preparing for the Live Lab? You lived in Athens, Georgia, for a little while, so I imagine you were fairly familiar with the city.

I didn’t spend a whole lot of time in Atlanta while living in Athens. The city’s traffic is something I got to know well, though. I often found myself in a rush to get to the airport, stuck in the car in summer with no air conditioner. . . . I photographed Easter Sunday at Ebenezer Baptist Church in 2016, and I remember feeling awed by the performance of the choir. I loved the international market on Buford Highway, with products from every corner of the world, each labeled with its own nationality. But I definitely wouldn’t say I was familiar with the city as a whole. I was in Athens for only a year and Mississippi for two years before that.

What were you originally planning to work on during the residency? How did you select the focus of your work during Live Lab?

It normally takes me a lot longer than ten days to develop a project, so this short time frame was unnerving. The only commissions I’ve finished that quickly are magazine assignments. But I chose to go slow and think of the Lab as a chance to start something.

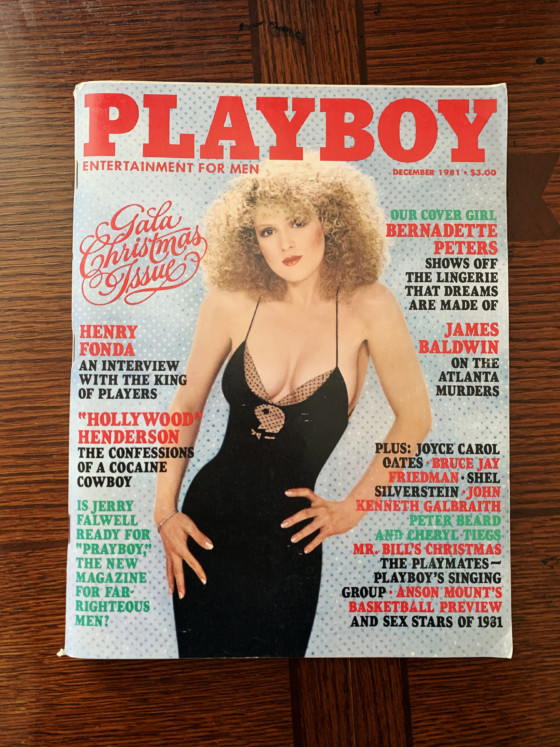

I went down a research rabbit hole in the months before the Lab, after I found James Baldwin’s book The Evidence of Things Not Seen (1985). The book takes the Atlanta Child Murders and public reaction to them as its subject but reads between the lines of evidence to expound on the status of racism and capitalism in America.

After reading the book, I ordered the 1980 issue of Playboy, where Baldwin’s article about the child murders was first published; listened to the Atlanta Monster podcast; read Giovanni’s Room; watched Gone with the Wind; then read an interview with Kara Walker about her relationship to that text, read Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark and Claudia Rankine’s essay in The New York Times about flying first class. I read contemporary magazine articles about Atlanta and about the child murders, in Rolling Stone, The New York Times; old reviews of James Baldwin’s book; and new articles about the reopening of the child murder investigations. I started reading about the history of polygraph testing and the racial biases they enable.

Baldwin says, “A writer is never listening to what is being said . . . he is listening to what is not being said . . . trying to discover the purpose of the communication.” I wanted to read Atlanta that way, considering the reopened child murders investigation as a way to look at the city’s relationship to truth and myth and its relationship with the past.

You got to spend one day in Atlanta before returning home to California. How did you spend that day?

The day I arrived, the producer for the Lab sent me a link to a Google map marking points where evidence in the child murders investigation was found, so I spent the morning driving to a bunch of these sites and took a few pictures with my phone.

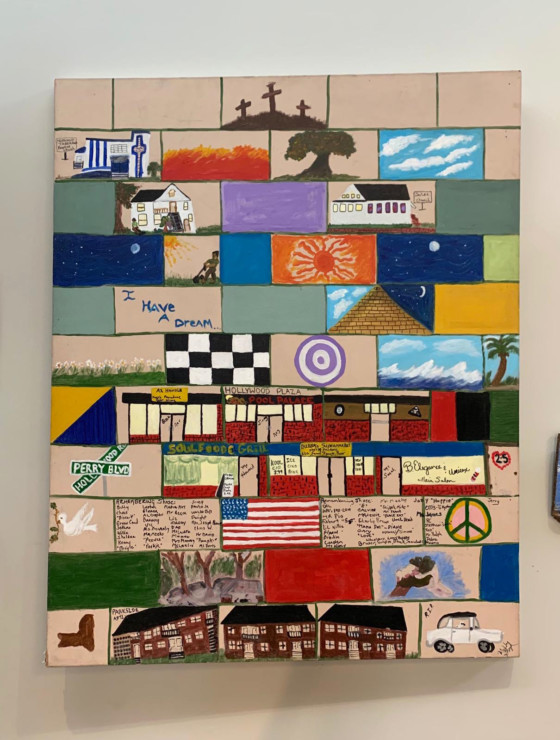

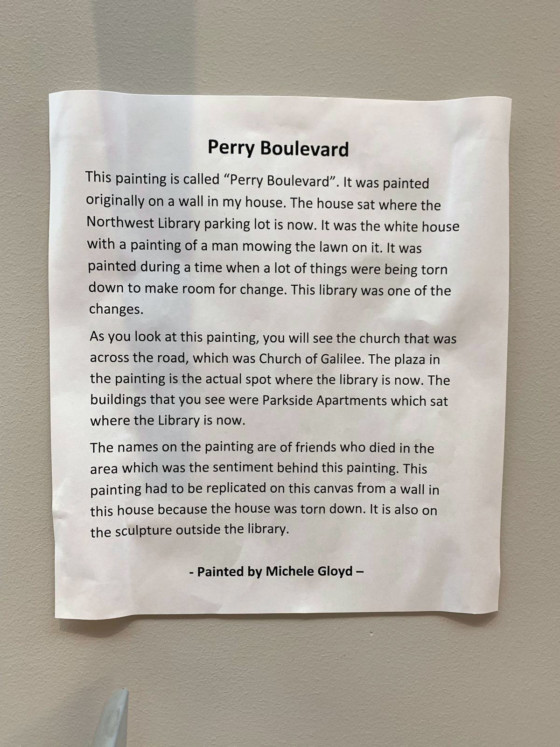

While looking for a strip mall called Hollywood Plaza, I found in its place a newly constructed library. Inside the library was a painting of the old neighborhood, and there I found Hollywood Plaza, a piece of evidence that’s been removed from the map of Atlanta but preserved in a small way in this painting.

That was the start and end of my time in Atlanta for the Live Lab. I hope we’ll be able to get back and carry on at some point.

Amid quarantine, how have you adjusted the work you’re doing? Upon returning home, did you carry through with any of your initial plans for the Live Lab?

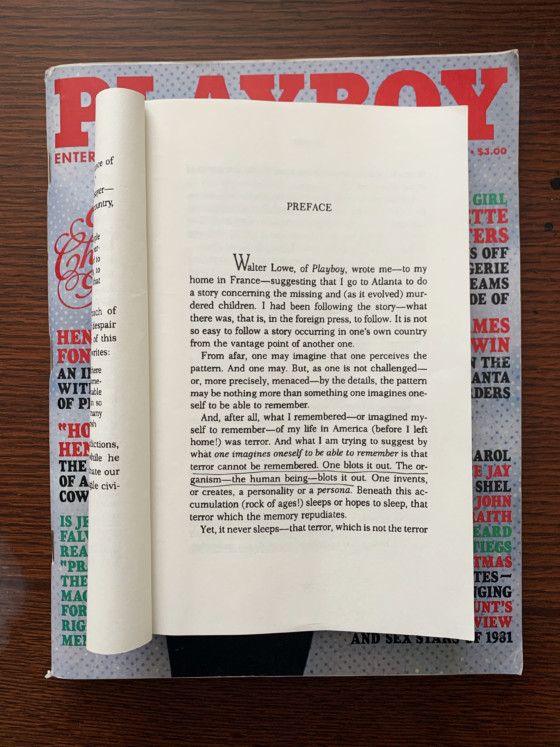

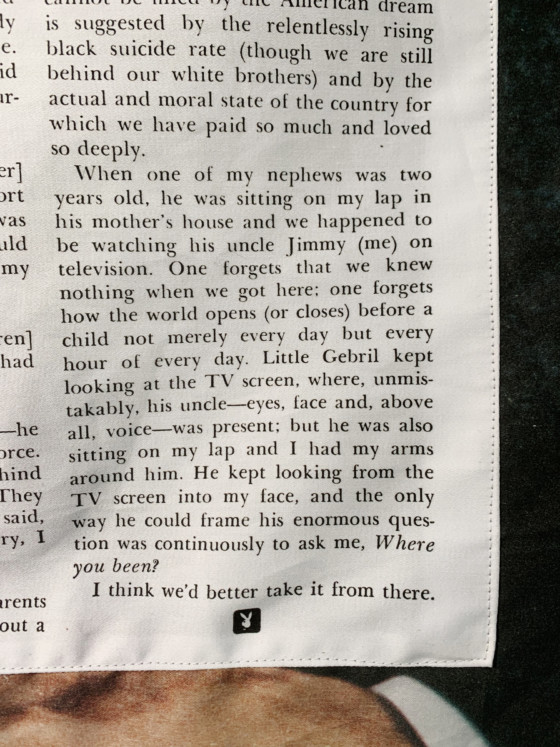

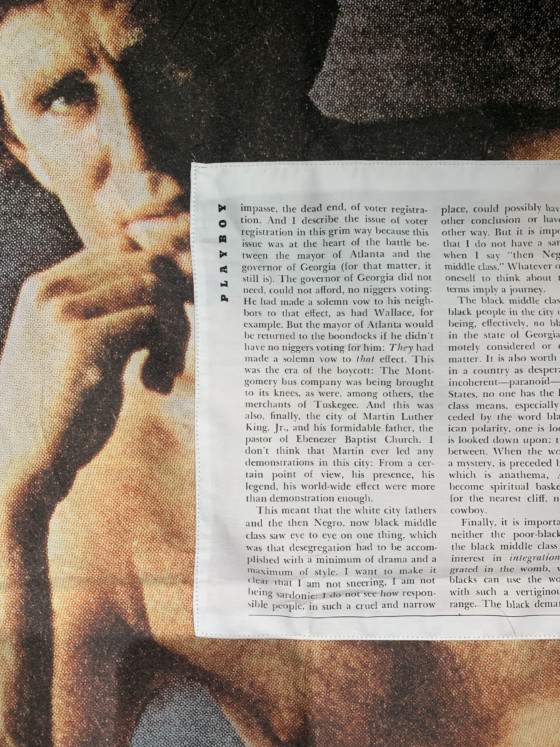

One thing I had hoped to work on during the Live Lab was a quilt made from the materials of the Playboy issue where Baldwin’s story was first published. I wanted to think about Baldwin’s article in relation to this magazine, so I tore out the pages, and took out the centerfolds and female porn and all the articles. What was left was a collection of advertisements promoting an ideal of white masculinity. So I put Baldwin’s very critical text about racism and America’s economic system, and sewed it over the backdrop of these advertisements.

What sparked your interest in the Atlanta Child Murders? What did you learn about the city through the lens of these events?

I wanted to read the story of the child murders and Atlanta through the lens of James Baldwin.

His book doesn’t ask who committed the murders. He looks back to try to understand: “neither whites nor blacks, for excellent reasons of their own, have the faintest desire to look back; but I think that the past is all that makes the present coherent, and further, that the past will remain horrible for exactly as long as we refuse to assess it honestly.”

He asks, why does a person legally charged with the murder of two men get tried for the murder of twenty-eight children? Where is the “pattern” to the murders when the facts show that one boy was shot, one was strangled one, one died of a head injury, one was stabbed, one was asphyxiated . . . ? Why has black death never before elicited so much attention?

How was it that the black demand for desegregation turned into a white demand for integration? What did that do to black institutions? Is it progress when the land on which black people live is reclaimed for luxury hotels and shopping malls? What was the original form of America’s “magic marketplace”?

Does a city with a black administration that is beholden to the laws of the State of Georgia play a role in the administration of “southern justice”? How does a child sort out reality? What do Walt Disney, Mammy, Aunt Jemimah, Scarlett O’Hara, and Manifest Destiny tell us about the way truth is processed in this country?

In past projects, you’ve collaborated with the communities you photograph and invited them to lend their own words and voices to the images. As you’ve been incorporating James Baldwin’s words into this quilt, how does that relate to other collaborative projects you’ve done?

The photo quilts I’ve been working on in the last couple years are more of an un-collaboration. I’m trying to subvert the meaning of texts and surveillance images I collect from the internet. I’m trying to take the air out of these materials that pose as evidence of neighborhood crime.

The Baldwin quilt is different. I’m trying to understand his words, trying to draw inspiration from his way of looking at the world. Maybe this is similar to the way I worked with the Wild Pigeon story, which was written by the disappeared author Nurmuhemmet Yasin in China. I selected pieces of his story and presented them alongside images from the project, giving this forbidden story a visibility it had been denied by the state.

When I first sewed the pages of the Playboy article onto the backdrop of the magazine’s ad images and stood back, the text blocks looked like a puzzle. I liked that, but I also wanted to find a way to draw the viewer in closer to read the text. But selecting short passages didn’t really work in this case. You can’t just read a sentence of Baldwin and be finished. One phrase draws on ideas that are not on that page, that are in other books, and that have proliferated elsewhere, so the challenges are different.

What I’m actually obsessed with right now is trying to think of imagery I can pull from Baldwin’s words, whether in a quilt or in a photograph that I make.

You’ve recently been exploring working with sculpture and fiber — quilting, for example. What do these other materials open up in your practice that you aren’t able to delve into with photography alone? And do you use photography along with these new techniques/mediums?

Ever since my first book designer, for Two Rivers, suggested laying out my pretty images so they flowed over the fold of the book pages, preventing the images from being seen as a whole, I have been thinking of ways to disrupt the idea of the documentary image as singular or evidentiary, complete and true. I’ve done that by inviting people I photograph to cut up my photos and remake them as collages (Wild Pigeon), by inviting people to perform and participate in the photo making process (Internat and Knit Club), and by merging photos and street fabric into quilts (Next Door).

I’m pushing myself to let one idea or process lead me to another. For example, while working on a time-consuming quilt during the lockdown, I felt the impulse to produce something with a more immediate result. I took the fiber materials I had been handling and sewing in the studio, brought them into my backyard, started building temporary sculptures, and photographed them as they grew.

While a quilt might take weeks or months to finish, I have to finish photographing these sculptures in a matter of hours in the morning before the wind comes in and blows them over. Like the “moment” in a classical documentary photo, the sculptures happened once. They are gone now, but a photo remains.

The Live Lab Photography Residency and Exhibition are organized by the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, and Magnum Photos. This project is funded by the Hagan Foundations.