From Black and White, to Color, and Back Again

From his earliest projects photographing South Carolina as a teen, to his seminal Greek work and his momentous move into color - Constantine Manos reflects on the evolution of his practice

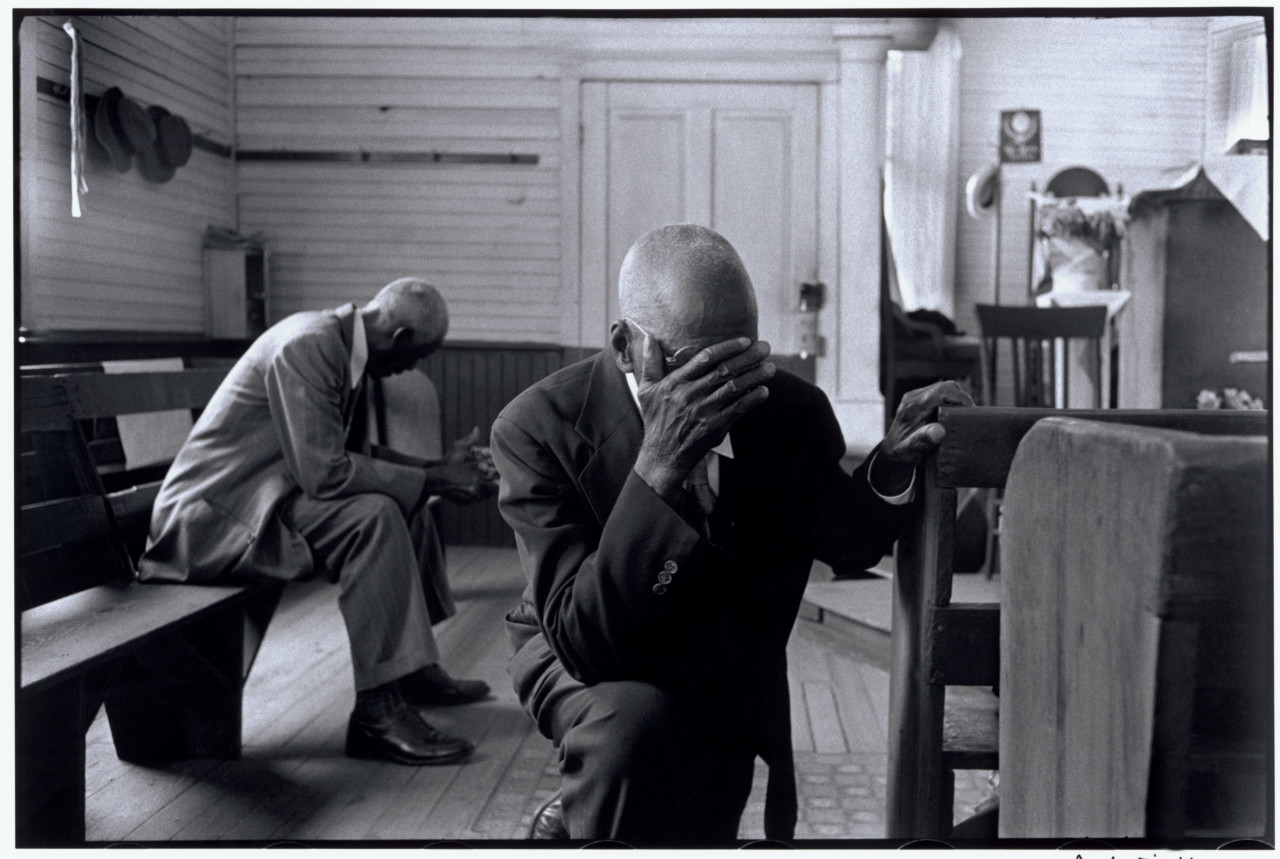

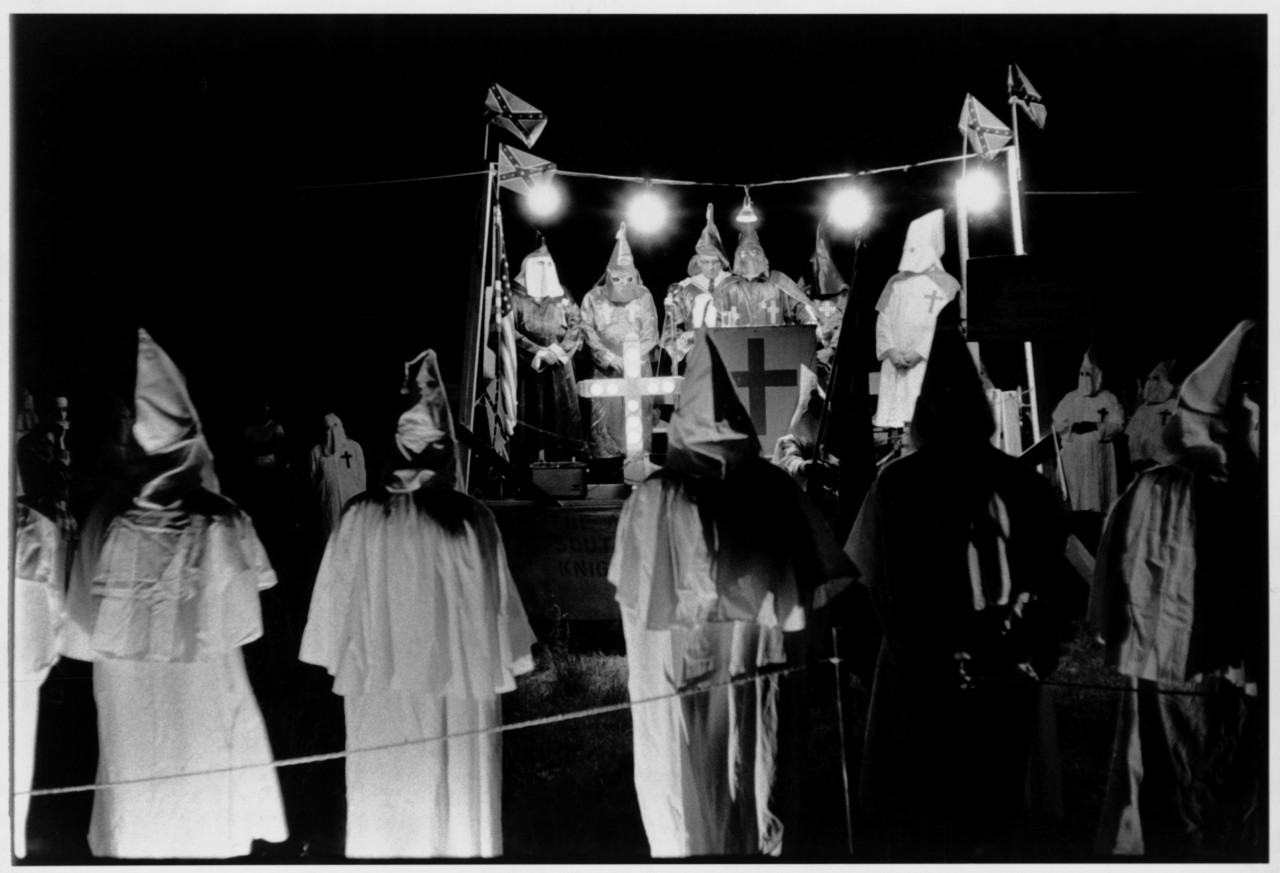

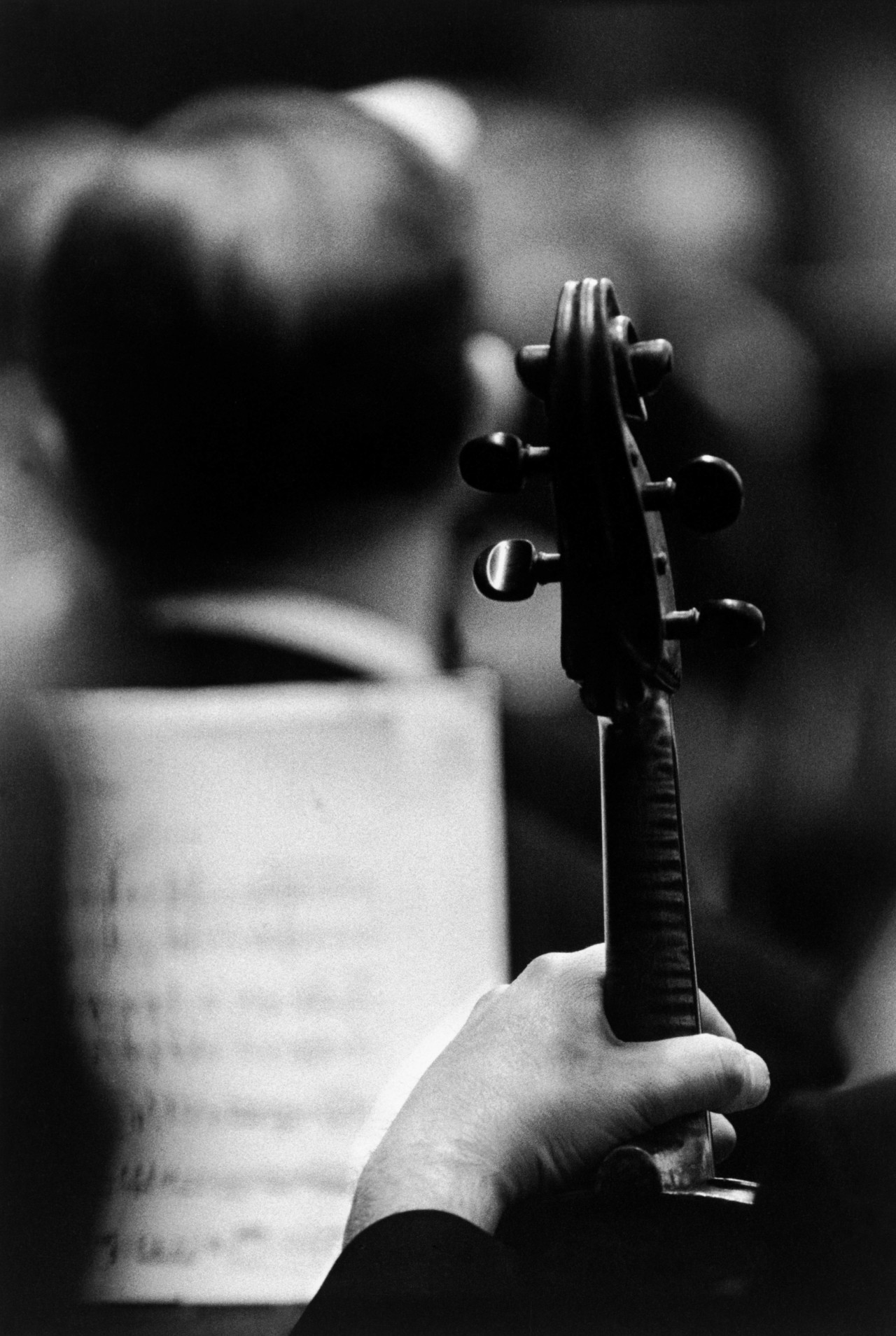

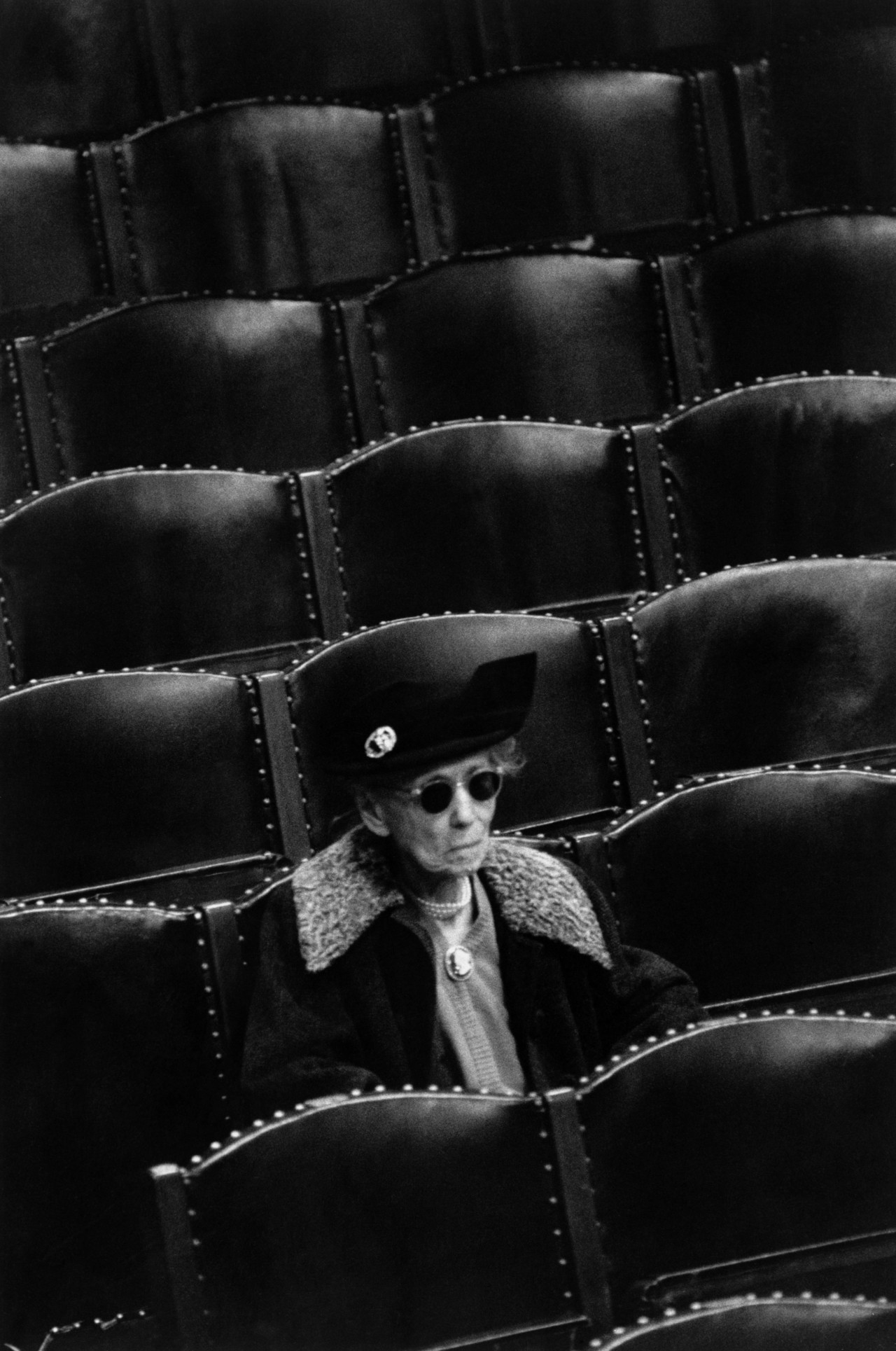

Born to Greek immigrant parents in the American South, Magnum photographer Constantine Manos first started photographing in his native South Carolina – a world he felt dislocated from as it writhed in the throes of segregation’s latter days and the growing momentum of the civil rights movement. Via building his own darkroom and joining his school’s camera club Manos found himself a professional photographer by his mid-teens, working for newspapers before landing his dream job in Boston photographing the city’s symphony orchestra. This led to his book, Portrait of A Symphony, published in 1960. These projects were all shot in black and white and led toward his career-defining work in the isolated villages of Greece. And then it all changed, as Manos wilfully switched to color, which resulted in two books – American Color and American Color 2.

Here, the photographer reflects upon his career to date – spanning formats, topics, and continents. From his early poetic studies of South Carolina and Greece’s isolated villages to his searingly vibrant photographs of a blue-collar America of bikers, cheerleaders, tattoos, and Pride parades.

In the earliest days of your making photographs, in South Carolina where you grew up, what was the initial attraction to the medium?

My interest in photography goes back to joining my school’s camera club at the age of thirteen. The year was 1947. I would later learn that this was the same year that Magnum Photos was founded. I was a good student, and I became entranced by photography. We had a wonderful, spinster teacher named Sadie Cox – who was very strict and a great disciplinarian. That’s where I got my training in the dark room. I learned to develop film, to make prints, and to be very fussy about temperature control. I got a great training in photographic craft from that school and teacher.

I set up my first darkroom in the basement of our house and built an enlarger from an orange crate and an old box camera. Later in my life, living in Boston, I would be the proud owner of a beautiful white formica darkroom. Throughout my life I developed my own film and made my own prints.

My first camera was a Kodak Brownie Reflex. My first proper camera was an American Ciroflex. From there I graduated to a miniature Speed Graphic and finally to a pair of Rolleiflexes. I was the sole photographer for my school newspapers and yearbooks through high school and college. At college at the segregated University of South Carolina, I majored in liberal arts. As well as photographing, I also wrote for the college newspaper. At that time I wrote my first anti-segregation editorials in the newspaper.

How did that early interest manifest itself into your first actual project. How did the transition toward professional work come about?

I was a professional from the age of fifteen, doing freelance work for The State – South Carolina’s largest paper. But when I was in college I came across an article in Popular Photography magazine about a photographer named Henri Cartier-Bresson, who shot with a Leica camera and used English Ilford film. In the same article I read that he was a founding member of a photographic agency called Magnum Photos. I immediately bought a Leica with a 35mm lens and ordered some Ilford film.

So all you needed then was your first real project to shoot?

I had read in a newspaper about a place off the coast of South Carolina called Daufuskie Island, which was inhabited by African-Americans who made their living gathering oysters and crabs. In 1952, at age eighteen, I hitched a ride on a boat to Daufuskie Island with my new camera and film and made the first serious pictures of my life, of which I am still proud. The first picture of mine that stands out from that trip is of three children running beneath trees covered in Spanish moss.

I then got on a bus to New York with my new pictures under arm to visit the offices of Magnum Photos. The first photographer I met was Cornell Capa, who looked at my pictures and said they were nice — then suggested we go for a drink. He took me to a bar down the street and asked me, ‘what will you have?’ and I replied ‘whatever you have.’ I have been drinking Scotch ever since. Capa told me to come back to see him once I had finished my compulsory service in the US Army, which I did.

Issues around segregation and race were a large part of your early work, was documenting the changing South a drive for you?

It was an important subject. I felt that the African-American people were held back, and I was on their side. I was very sympathetic to them. We were Greek, and in a way we were outsiders too – outside that typical Southern world. I didn’t connect with the things that were happening in the South at the time. I wrote a series of three anti-segregation editorials in The Gamecock — the student newspaper at the University of South Carolina. We got threatening phone calls to our home.

You moved north next and came to publish your first photobook. How did that come about?

I lived and freelanced, after my service in the Army, in New York. In 1953 I got a dream job as a photographer for the Boston Symphony Orchestra. I had always loved classical music, and I was popular with the orchestra because I was the first photographer that had photographed there without using flash. I photographed Leonard Bernstein, Isaac Stern, Rudolf Serkin and others. That work became my first picture book, Portrait of a Symphony.

"I was popular with the orchestra because I was the first photographer that had photographed there without using flash."

- Constantine Manos

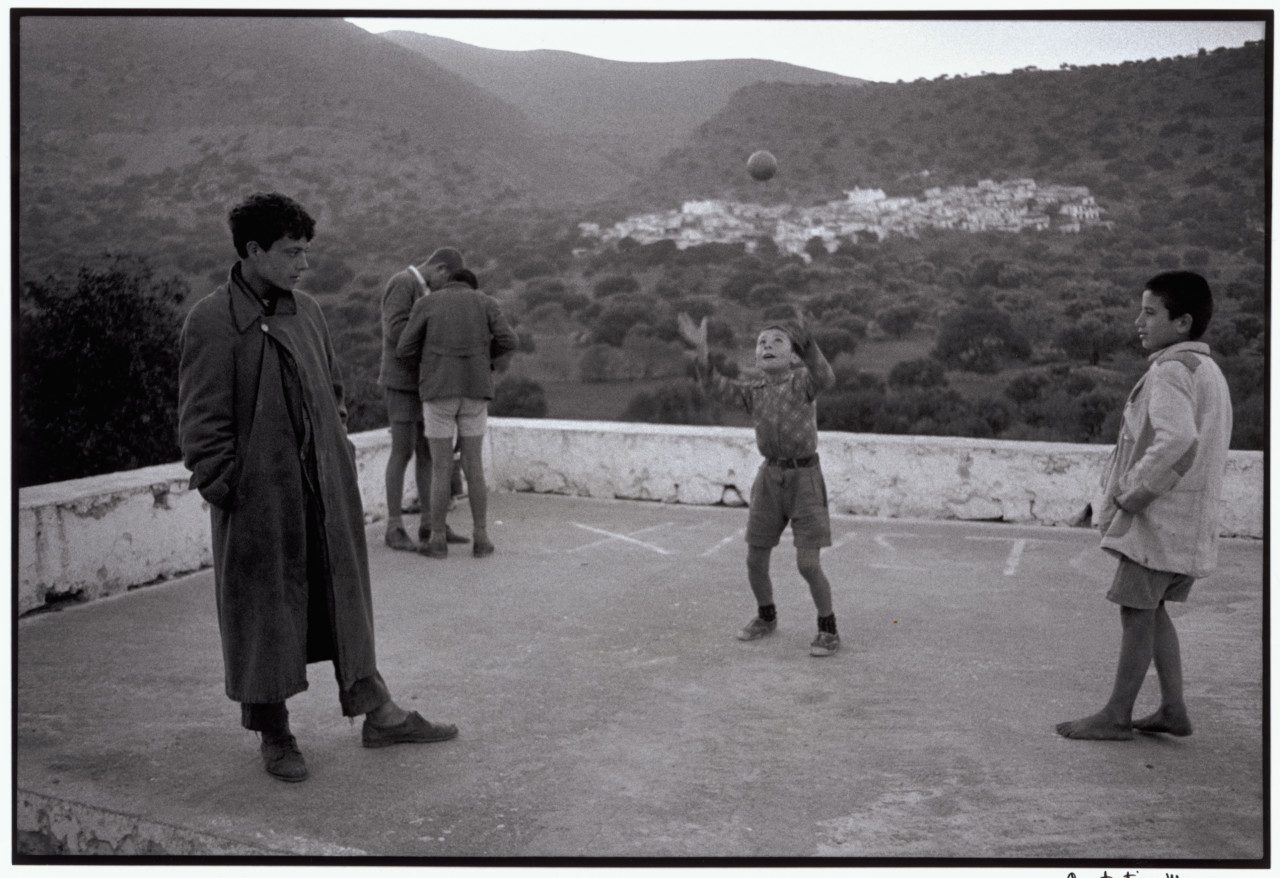

Your second book, A Greek Portfolio, saw you completely changing your focus. From the immediateness of South Carolina and segregation, or your long-running love of classical music, you found yourself in Greece. Working in isolation.

My parents were refugees from a Greek village in Turkey. They had to leave in 1922, and leave everything behind. So I had grown up hearing so much about the horio — the village — and I was intrigued. I felt I needed to pursue a project close to my heart. I went to see a publisher, a wonderful man in New York named Frank Taylor, I showed him my book on the orchestra and he gave me some money as an advance for a book on Greece.

I packed a big trunk of classical LPs, a small record player, and shipped it to Athens. I flew there a took a little apartment where I set up a little dark room. I needed a sink made and asked around about what the cheapest material to use was. The Greeks told it was marble! Next to the cemetery was a place where they made tombstones. I gave them the dimensions and asked them to make me a sink of marble and deliver it to my apartment, but they only delivered to the cemetery. Some friends helped me get the sink to the apartment in a rented truck.

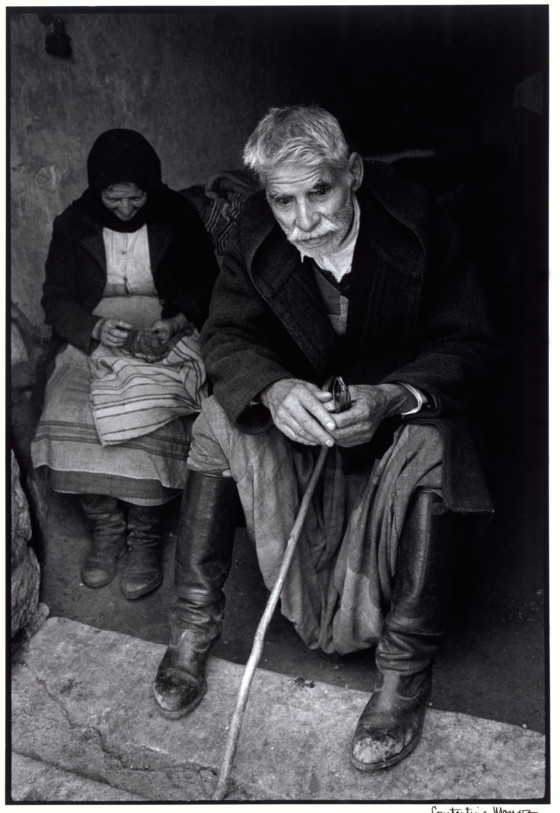

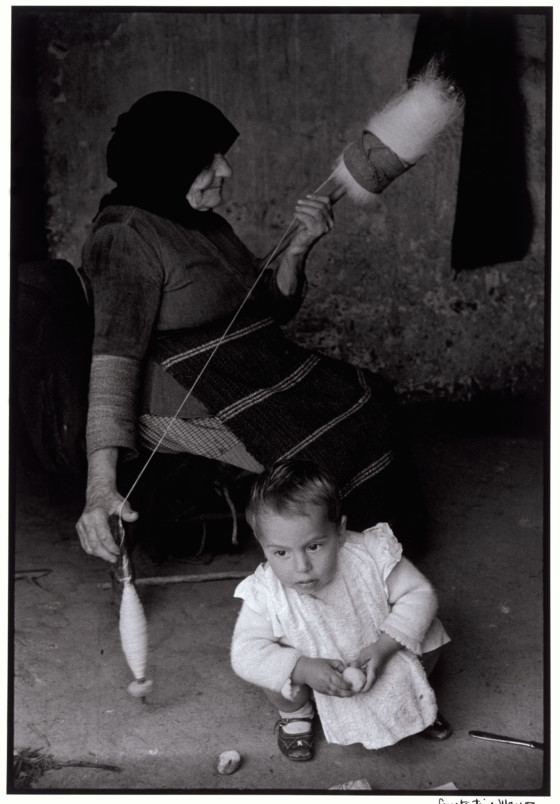

"They had their olive trees, their goats, and they were the salt of the earth."

- Constantine Manos

I got a Volkswagen Camper with a bed and toilet in it, and I drove all over Greece. I would only photograph in isolated villages, which had no electricity. I was searching for a beautiful and poetic look in my pictures and found it in the people. They had their olive trees, their goats, and they were the salt of the earth.

I am a people photographer and have always been interested in people. I also have always looked for a moment in my pictures. I have been very serious about photographing people as individuals, as human beings. I don’t think I have ever taken a photo without a person in it.

After a while I had to leave Greece because I found that I was subject to being drafted into the Greek army if I stayed over a year. I left Athens in my little Volkswagen and drove to Paris. I left a box of my Greek prints in Magnum’s office there. Months later I was back in Greece on a remote island. A friend in Athens forwarded my mail to me. In the mail was a letter from Magnum Photos inviting me to become a member. I was thrilled to death, but had no one with whom to share my happiness. The year was 1962.

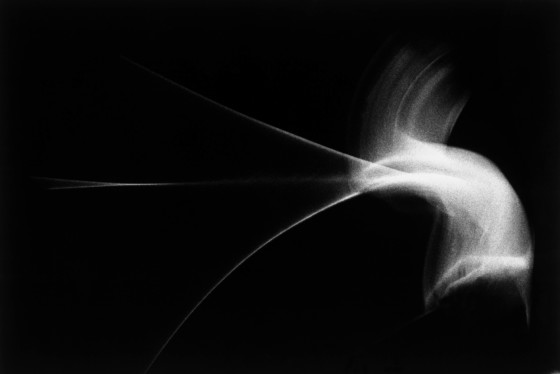

A Greek Portfolio seems like a turning point. From there you turned to the colour photography for which you have become well-known for. How did that huge change in your work come about?

The Greek book was very important to me. It was a watershed. After that project was completed I went back to New York. I was doing a lot of commercial work such as advertising and corporate annual reports to make a living and pay the rent. The money was good, but I was in a bit of a rut.

I needed to do something that was my own that was not an assignment or for Magnum. That’s when I began traveling around the USA photographing Americans of all walks of life in color. It was a radical change for me, and it was certainly a conscious effort. I was looking for a completely different style of picture from my Greek work. I photographed Americans in color, specifically Kodachrome.

"I hope I can create a book of photographic poems, each unique yet all connected."

- Constantine Manos

I decided, on my own nickel, to go to California for two weeks and take my Leicas. I stayed in cheap motels and went to places like Venice Beach. Later I went to Bike Week in Daytona Beach. I wanted to shoot in places where people gathered to revel and be free. Bike Week was a very rich place for me in terms of making photos of that kind. Having being brought up in a Greek immigrant family I was very fascinated by the Americans. And I wanted to photograph them in color.

I had such a good time producing American Color that I decided to do a second book, American Color 2. I think those two books represent an important body of color work, they aren’t just pretty pictures and there is some depth to them. I think the result is a celebratory picture of America. I made those pictures whenever I had time, and I think that’s the best way to make a body of work – not having an editor waiting for you, just doing it on your own — using your own money and time.

American Color 2 was your most recent book, how did your photographs develop from there and what are the constants you see in your work, the unifying aspects that tie such disparate subjects and formats together?

At this point in my life I plan to return to black and white and will be photographing in the small and interesting seaside town where I live. I will be using a Leica with a 35mm lens, which most closely approximates what the human eye sees. I hope I can create a book of photographic poems, each unique yet all connected.