Music, Pleasure and Photography

Cristina de Middel on the inspiration offered by breaking with day-to-day logic and limitations through musical thinking

In the second instalment of Magnum’s series on photographers’ non-photographic sources of inspiration, Colin Pantall speaks with Cristina de Middel about the surprising role of musical theatre in inspiring her to make her work, which exists in a grey-zone between art and reportage – a Dadaist approach she sees as a hopeful alternative to the more conventional ‘discourse of sobriety’.

“I’m 44 years old and I remember as a kid me and my sister and brother would just watch the five or six video tapes that we had. And my father had a very specific taste in music,” says Magnum photographer Cristina de Middel during a WhatsApp interview from Spain.

“We just watched these movies over and over, and it became normal for me to start including all these melodies and songs in my everyday life. Now, of course, I cannot do it – because I’m a serious grown up woman – but I imagine doing it all the time. What would happen if I started singing a song here? It happens often – in airplanes for example when the air steward is giving safety instructions, I imagine it all becoming a scene in a musical with all those on the plane dancing.”

It’s the directness and the looseness of the musical narrative that attracts de Middel. Anything can happen in a musical. The lame can walk, the blind can see, time, place and mood can change, and all from the first note. Even in films not centered around music, the soundtrack serves to change how we think and feel about a scene, a location, a character. ‘How strange the change from major to minor’, wrote Cole Porter exemplifying the way in which music can swing our mood from happy to sad in an instant.

“I love music because it’s so different to what I do, and it triggers so many ideas. I have found myself in difficult situations where singing could break logic and give me a way out of that difficulty.” Reflects de Middel. It’s the idea that music can move people out of their ingrained patterns of thinking and being. Singing a song in a time of confrontation changes how we think, how we feel she explains, “People do not expect you to sing. They expect a confrontation where they can say something to upset or hurt you, but if you respond by singing, they don’t know what to do. It [breaks with] that logic. And then you win.”

The idea that this musical approach can move us away from confrontation into a space of pleasure and contemplation is one that is transferrable to images. Look at Esther Vonplon’s work on melting glaciers and listen to the accompanying requiem and sound of melting water and you are transported into a sorrowful place. The audiovisual version of Mark Power’s Die Mauer ist Weg brings a joyfulness to the fall of the Berlin Wall, while David Alan Harvey’s Based on a True Story multimedia transfers the energy and immediacy of the samba soundtrack to his images of Rio de Janeiro.

"The possibility of breaking that logic where there is a pattern of behaviour, of serious behaviour, with a slight modification of reality, makes anything possible"

- Cristina de Middel

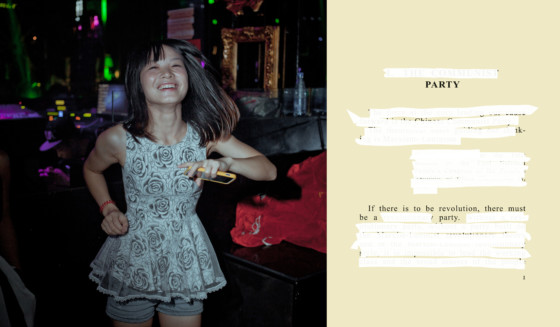

“Musicals break the logic of everyday life. We are all programmed when we are raised to behave in a certain way and I try to fight against that. The possibility of breaking with that standard logic – the engrained patterns of behaviour, of serious behaviour with a slight modification of reality, makes anything possible and makes you able to understand reality in a different way. It gives you a new perspective on the world.”

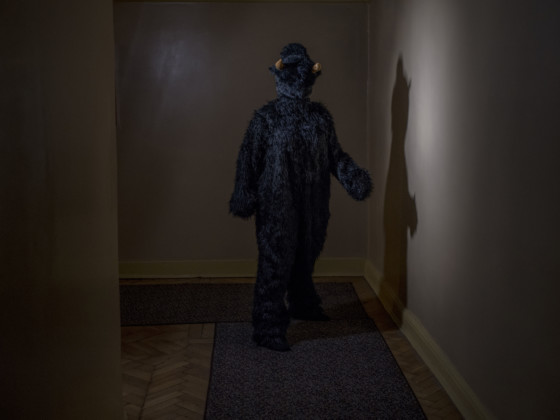

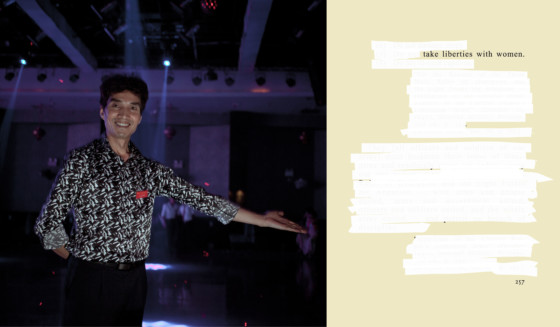

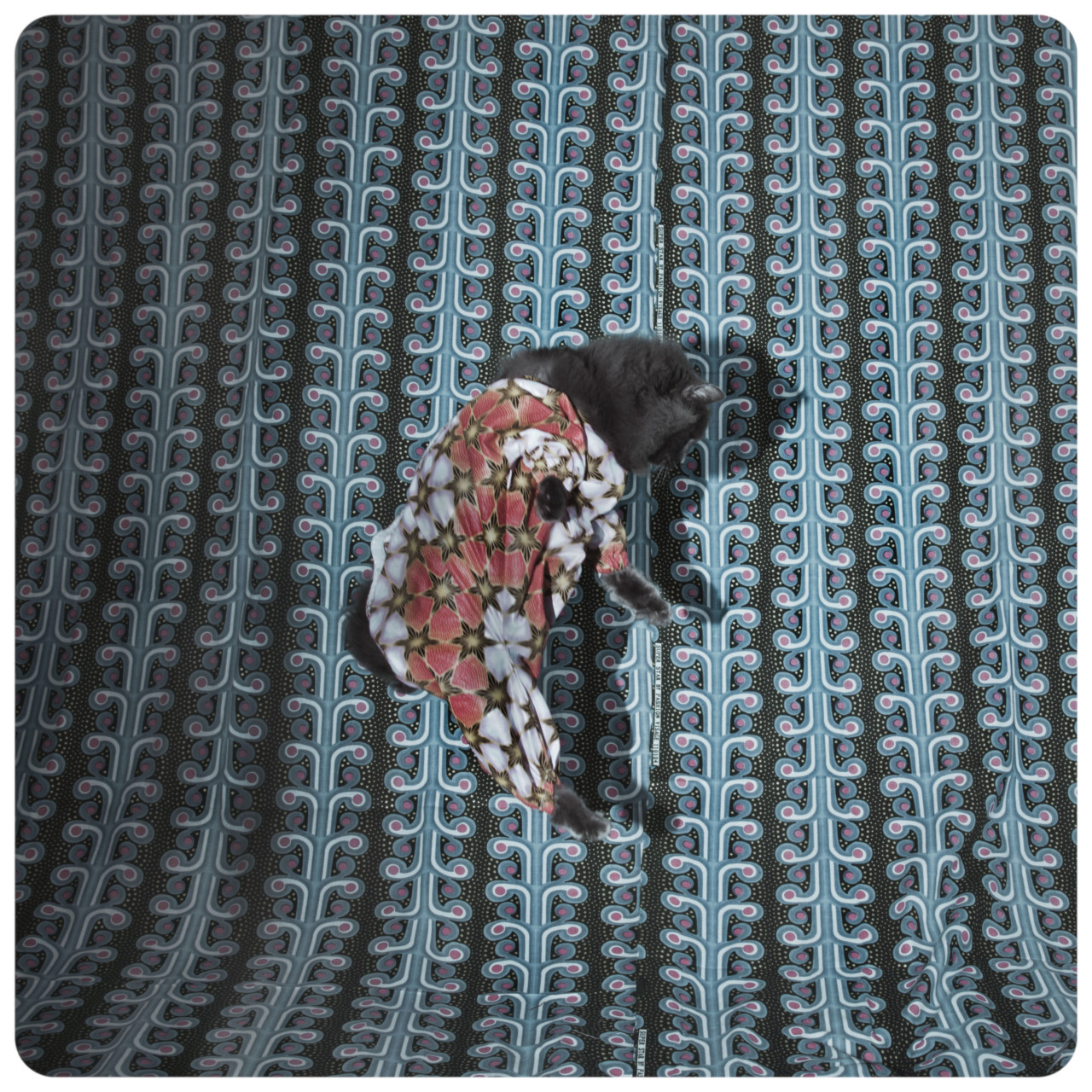

“It’s the same with photography. We are all used to seeing things in the same way with the same logic. Breaking that logic by showing things in a different way can offer new perspectives.” De Middel creates these shifts in her photography, whether this be through the fabrics used in the uniform of her Afronauts spaceman, the transformation of a hotel room into a stage set, or the way a hired assassin jumps in the desert in the middle of a shoot.

“I change small details, but that has a big impact on how we see things. It’s a sort of surreal Dadaist approach to reality. Changing these little things gives a different dimension to your reality, to your behaviour, and to your reactions. And we need that because we’ve been making the same mistakes over and over… The serious, Cartesian approach to reality is no longer offering many good results. So maybe Dada can help.”

"Photography can be playful and propose more questions than it gives answers. That’s the greatest thing photography can do – raise questions"

- Cristina de Middel

This idea also ties in to the way we make photography, the way we talk about it, the way we think about it. Mention a musical film, perhaps West Side Story, Om Shanti Om, The Wizard of Oz, or Sholay, and our eyes light up and we talk about it with the language of pleasure. Mention a documentary and we talk about it with what has been described as ‘the discourse of sobriety’. Our eyes narrow, our lips purse as we try to discover exactly what is wrong with these images. And it’s usually quite a lot; we find ourselves lurking in a cloud of judgement. The territory inhabited by this idea of document is limited, austere, and owes much to a patriarchal, monotheistic world view of knowing what is best for others.

It’s a way of seeing photography that de Middel is eager to shift. “I do not think that photography is just serious and documentary. There are many different photographers who have used a more relaxed and playful form of photography. We stick to the serious form because it is the serious form that has received more support over the years, but that doesn’t mean we have to carry on sticking to it. Photography can be playful and it can propose more questions than it offers answers. That’s the greatest thing photography can do – raise questions.”

“Magnum has traditionally been known for documentary work, but documentary can have many voices. And right now, there are new languages being made, there are new photographers working in different ways, and photography is being received in new ways.”

“I have a broad understanding of what documentary is. If you think of the very origins of documentary, it was troubadours going from town to town spreading the news. They used song and verse and music to tell these stories, and that was documentary. All the monks in the abbeys making illuminated copies of bible stories – that was creative language, right there.”

“It’s quite a new idea, this assigning veracity and truth to things. We’re right at the moment where we are going back to a more creative understanding of what truth is. It should open up the debate between truth and reality and explore what the link between them is. I don’t think photographers can answer that question. It’s a huge philosophical problem, essentially it’s metaphysics, and photographers aren’t metaphysicians.”

The musical also shows you narrative mode that is used and how that can instantly change how a story is received. “If you think of West Side Story – that is a musical approach to telling a story, but you can also have the Shakespearian approach to the same subject matter in Romeo and Juliet. The way you address the subject and the way you consume it is totally different in these two cases. But still, you are presenting the audience with a confrontation between two groups of immigrants. There’s this power of the big families and the power of tradition and the movement of people from one place to another. You can tell this story in so many ways. I prefer to understand the world through the musical, but it doesn’t mean I don’t like Romeo and Juliet.”

“I think [this musical way of thinking] opens up different ways of understanding because photography has been very divided between the black and white poles of documentary and art. But having a more relaxed perspective gives us more of a gray scale and it’s within that gray scale where you find the tension between subjects and territories that have usually only been explored on either end of that spectrum. When you look at these subjects from the middle, from that grey scale, you can take advantage of both ‘ends’, documentary and art. You can use a creative personal language to open up the debate to different audiences who you couldn’t address if you were only working from a purely documentary or art perspective. So you’re widening the debate and you’re widening your potential audience because you’re working with both extremes.”