Danny Lyon: A Life of Dissent

The photographer talks about his new film “SNCC” and the first published collection of his writing, American Blood

On the occasion of the publication of American Blood: Danny Lyon, Selected Writings, 1961-2020 and the completion of a new feature-length film, ‘SNCC’, about the early days of the Southern civil rights movement, the photographer and filmmaker Danny Lyon recently spoke with writer and editor Randy Kennedy for a talk about his life and work.

Kennedy is an American writer, editor and curator. He worked for 25 years as a writer for The New York Times, for much of that time covering the art world. His first novel, Presidio, was published in 2018 by Simon & Schuster. He is currently director of special projects for the international art gallery Hauser & Wirth.

American Blood is available from Karma Books here, and in a special edition here. You can see a trailer for ‘SNCC’ at the bottom of this article.

The following are condensed and edited excerpts of the conversation.

Randy Kennedy: Hi, Danny. It’s hard to believe it’s been more than a year since I’ve seen you! But for a while there, when we were editing American Blood together, it felt as if we were on the phone every single day, joined at the hip. Maybe we could start today by talking about the film? I just re-watched it. Both times I’ve watched it, I’ve cried, which isn’t something I do very often with movies. It’s just very powerful. It struck me that it’s not only about one of the most momentous periods in American history but also just about kids who were in their 20s when they carried out a pivotal social revolution, and now they’ve grown old and they can see what’s been accomplished and what still hasn’t. You were there documenting the movement almost from the beginning, and you kept up friendships with many of the participants, chiefly John Lewis, whom you describe as being like a brother.

Danny Lyon: I’ve always called myself a “documentarian” in quotes. Whenever I think about making films, I think about a great moment in a Michael Moore film when he’s filming Jesse Jackson on camera, and he has a big tape recorder, and Jackson says to Moore, who’s trying to be this important, consequential filmmaker: “I think you need to push that red button over there, don’t you?”

Kennedy: How do you think you became the kind of person who, in his early 20s, had the sort of political and moral fervor that you did, to go immediately to the South when the opportunity arose. You were a middle-class doctor’s son from Queens.

Lyon: I’ve been working on a memoir, a memoir that is now looking for a publisher, and I keep wondering about that myself. Both of my parents were immigrants. I went to school at Forest Hills High School, where Simon and Garfunkel were classmates and so folk music was already in the air. There were 4,000 students in the high school, and I think it was probably ninety-five percent Jewish. Nobody thought of it that way, because if you’re in the ocean, that’s the ocean you’re in. But I knew that America was different, that there was another America, and I had this huge desire to get out of there and see it. I remember the first time I reached Texas, I was so excited to be there I climbed up onto the granite monument that they have at lots of points where you cross the state line to have my picture made.

Kennedy: As a born and bred Texan, I fully endorse that was a way to enter the state for the first time. Your family also had some insurrectionary history, didn’t it?

Lyon: The Russian side was involved in the 1905 revolution. My uncle Abram played a part in the first-degree murder of a policeman, and came to America fleeing the draft. My mother arrived later, at the age of fifteen and was a garment worker who got fired for being a Communist. My family were not really Communists, but they were Mensheviks, back in the day when that was really revolutionary. Both of my parents talked about the Spanish Civil War, and even though I wasn’t alive when that happened, I felt as if I’d missed something important. When the civil rights movement began, I started paying attention. I think about 1961, Dr. King got arrested, and it made The New York Times, and I wanted to go there. I doubt I even had a camera by then. I didn’t have a car. I had no way to get there.

Kennedy: How did the opportunity arise when you were at the University of Chicago?

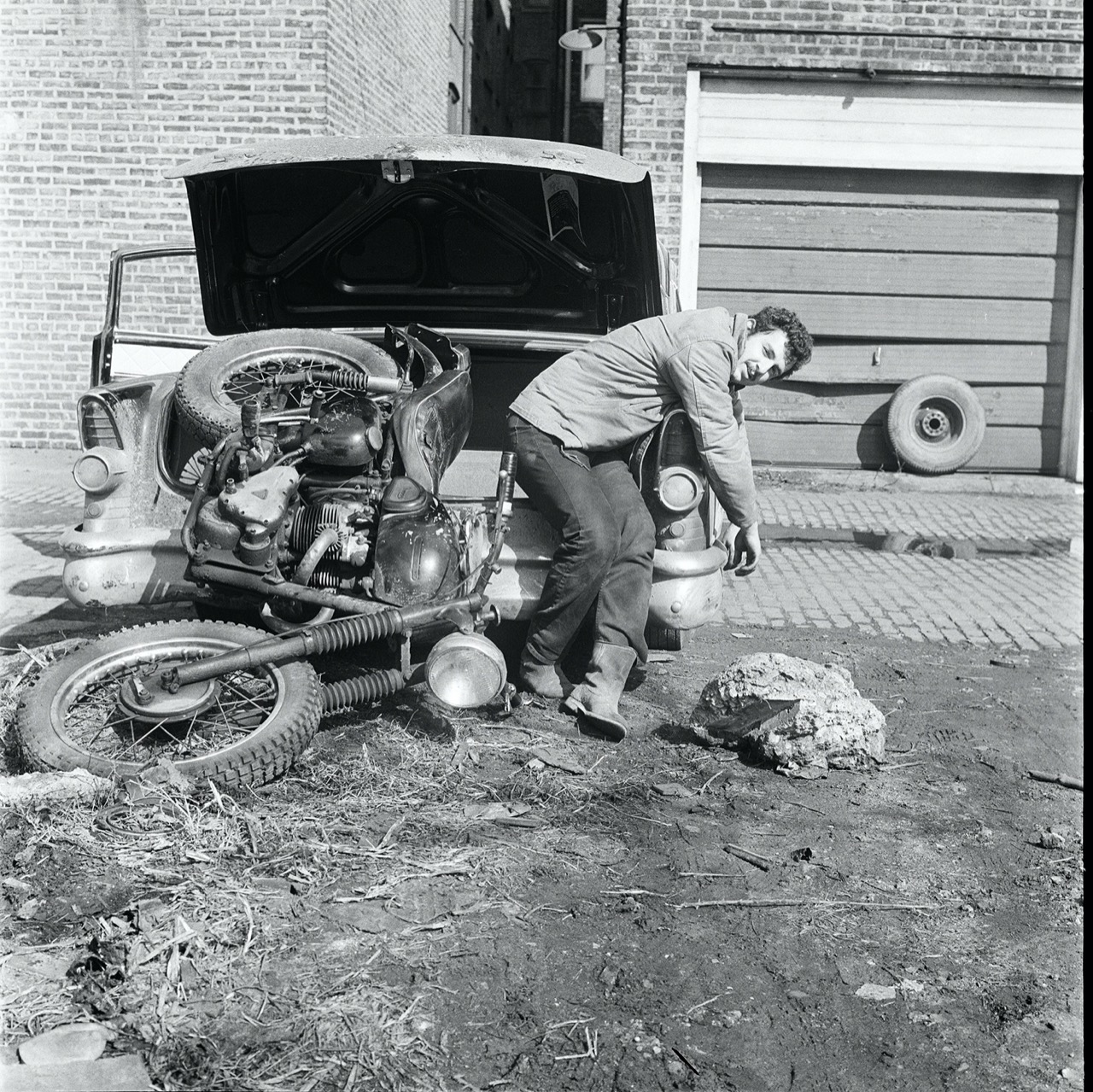

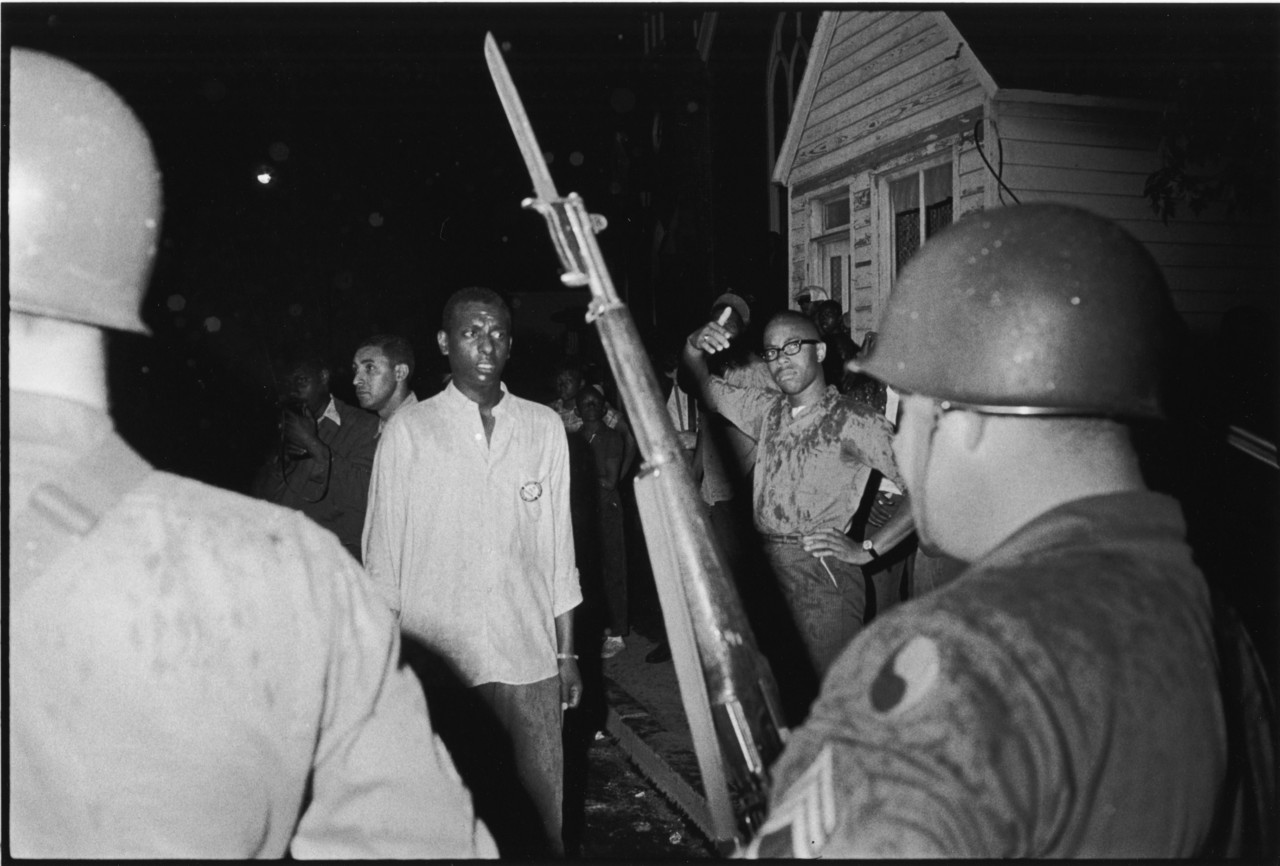

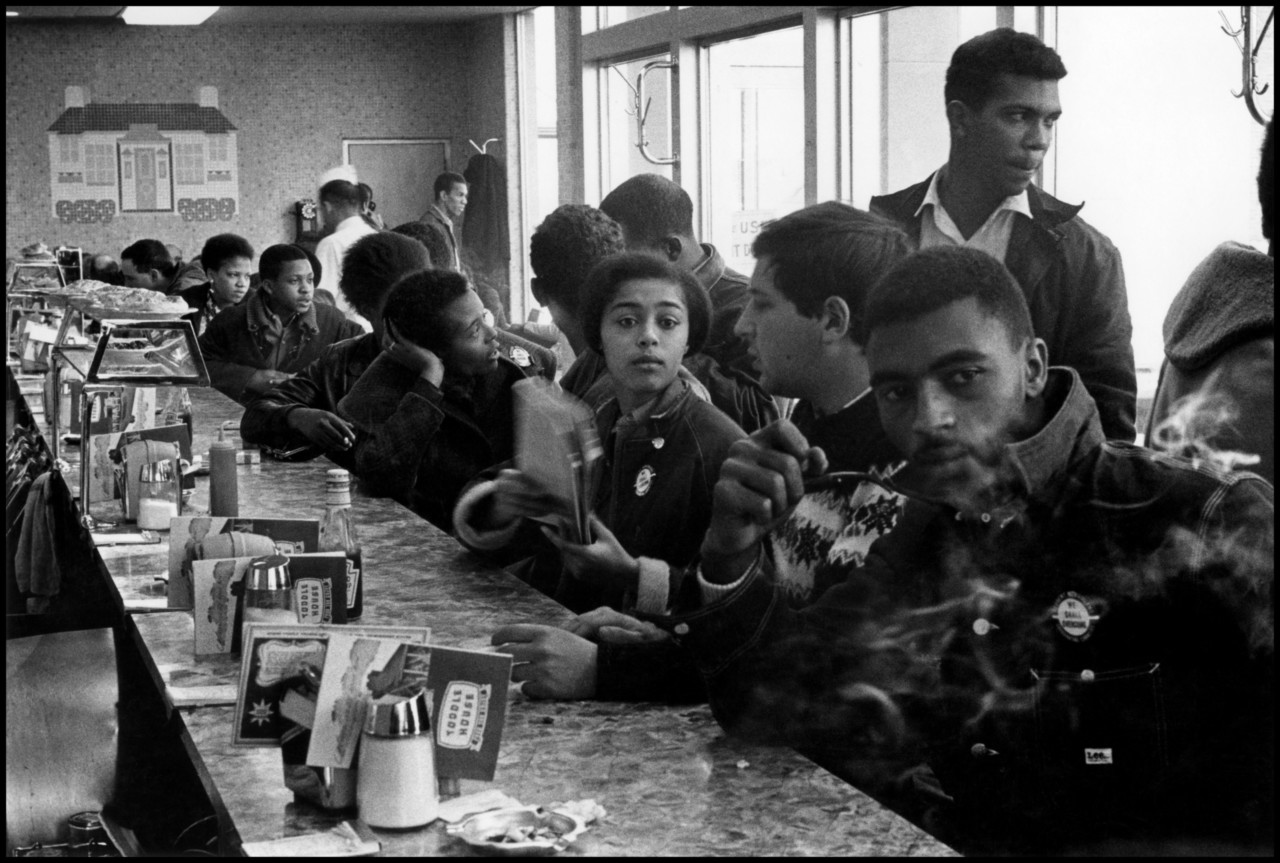

Lyon: I’ll tell you, but I first want to make the point about those years — that people forget what the feeling in the country was, because history gets changed over time, and it gets changed mostly because we see it on television and in movies, which are distorting and reductive. People in general were not crazy about the civil rights movement. They didn’t all say, “This is wonderful!” Most people said, “They’re breaking the law. There’s violence. Why can’t the Negroes just be happy down there?” That kind of thing. There were demonstrations at the time in Cairo, Illinois, which is about four-hundred miles from where I was in Chicago. This is like you listening in Manhattan, and something was happening on the Canadian border, not really so far away. A Jewish student named Linda Perlstein, one of my classmates, had been arrested in Cairo. And another thing was that, as a campus photographer, I’d taken pictures of the first civil-rights sit-in at the university. It was mostly white kids, and one of the leaders was Bernie Sanders, who was my friend Ira’s roommate. And I photographed that, but I remember thinking at the time, “This is not the real thing. The real thing is in the South.” The other factor, if I’m being honest, is that my motorcycle had broken down, and I couldn’t ride it and take girls on rides, which was what I did. It was summer and I had nothing to do, so I got contact information from Linda Perlstein, and I hitchhiked down. I met John Lewis the very next morning.

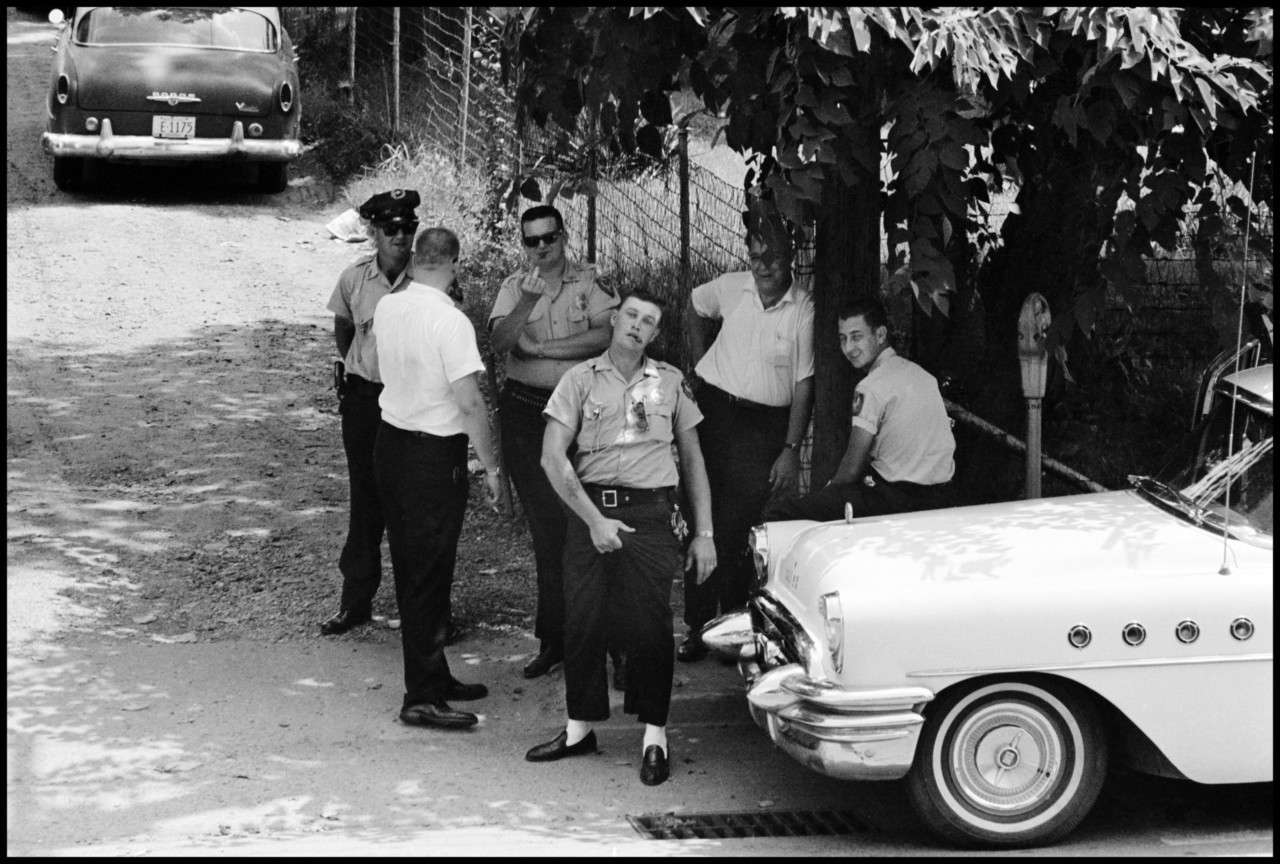

Kennedy: You talk about in the film about being surrounded by police officers, and literally physically shaking. Was there a point early on when you thought, “I’m in over my head. I shouldn’t be here”?

Lyon: I have mixed feelings about thinking about that. On the one hand, yes I was scared. But it’s obvious I also loved the adventure. The great curator in Germany who did my first retrospective in 1994, Ute Eskildsen, interviewed me once and asked me: “Did you do this stuff because you wanted to have adventures, or did you do it because you wanted to be a great photographer?” I found that question insulting at the time. “What do you mean? I’m a photographer. I was going to be a great photographer!” But, you know, as I got older I thought about it and I think she was right. I loved the adventure as much as anything. This stuff was great. It was straight out of Graham Greene. I arrived at night in Cairo, got a phone call with instructions. It was all cloak and dagger. Even John Lewis, who is the real deal and helped to create the civil rights movement, said to me later when I was recording him how much he loved this period. It was like Spain during the civil war. It was an extraordinary period, and I think everybody who was touched by it loved being part of it.

"People in general were not crazy about the civil rights movement. They didn’t all say, “This is wonderful!” Most people said, “They’re breaking the law. There’s violence.""

- Danny Lyon

Kennedy: James Forman, as you’ve said to me many times, was really the architect of how the SNCC operated and how it changed American opinion through a brilliant use of propaganda. Why do you think he trusted you to be the Committee’s photographer?

Lyon: Well, Forman was a remarkable person, and he’s really kind of been forgotten about by history. He was older than most of us, and he was very sophisticated. He’d done graduate work at Boston University, looking at mass social movements. I met him, and I’m a kid with Nikons, and he said to me, literally, in Albany, Georgia in 1962: “You’ve got a camera? Then go into that courthouse and photograph the water fountains.” There was a regular fountain marked “White” and a little bowl of the kind you’d give to an animal that said “Colored.” I remember how scared I was. Because it’s the courthouse. That’s where the sheriff is. These guys have guns and cattle prods and they’re nasty. But I took the picture and came out and said, “Okay. What do you want me to do next?” Maybe that impressed him. And he started taking me around with him.

Kennedy: Did you develop anything to show to SNCC people while you were in the South on that first trip?

Lyon: No, and I was very worried about losing my film. One of the reasons I left town was I wanted the film developed. My last day in Albany, the cops all threatened me, and I thought, “Let me get the fuck out of here with my film.” I knew it was going to show people in the North things that they wouldn’t believe existed.

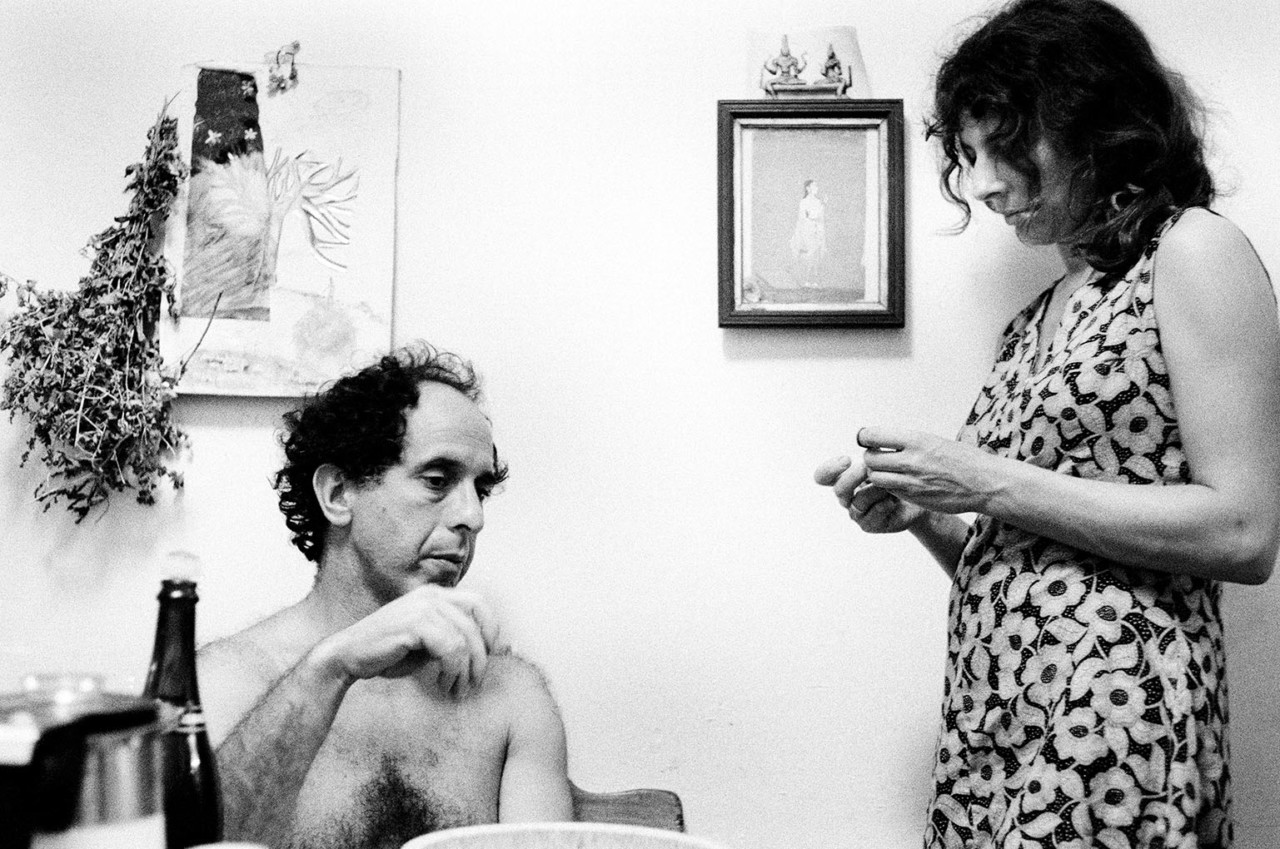

Kennedy: Switching forward about a decade, when you made your first film, Social Sciences 127, about the Houston tattoo artist Bill Sanders, in 1969, had you already been thinking about wanting to do film and not only still photography? Where was the transition point?

Lyon: By that time, I’d made the civil rights pictures, I’d joined the Outlaws, done the book The Bikeriders, done the work for The Destruction of Lower Manhattan, reached Texas, was working on the Texas prison book. I bought an inexpensive crank-up 16mm Bolex, I think from a hippie woman, and I took it into the prison, just to try shooting some footage. I had the example of Robert Frank, who had become a filmmaker. I knew his history, and I knew him personally. You know, they said of Hitchcock that by the time he finished writing a film, he was bored on the set because he knew exactly how it would come out. At that time, I knew exactly how Conversations with the Dead, the prison book, would come out, because it was all inside of my head. Every time I made a book, I tried to make it different. I really saw the book as an art form. After the prison book, I thought, “Well, what am I going to do now? There’s literally nothing more I can do with this form.” And I think that proved to be true. I couldn’t think of any new way to make a book. I met James Blue, the director of the Media Center at Rice University and he told me, “I can get you money to make a prison film from the American Film Institute, which was kind of new then.” And I said, “Great.” And I wrote a proposal based on my prison pictures, and I called it American Underground and said, “I want to make this film.” But actually I had no intention of making that film. I knew the film I wanted to make was about this very eccentric tattoo artist, who I saw as a kind of Falstaffian figure. I saw myself as a devious person in the way I went about getting support, and I kind of enjoyed it. I was a great liar. And it worked for me. I mean, I had snuck into the Texas prison system. They didn’t have any idea what I was really up to.

Kennedy: You worked on the new film, ‘SNCC’, off and on for several years, and some of the footage goes back more than a decade, right?

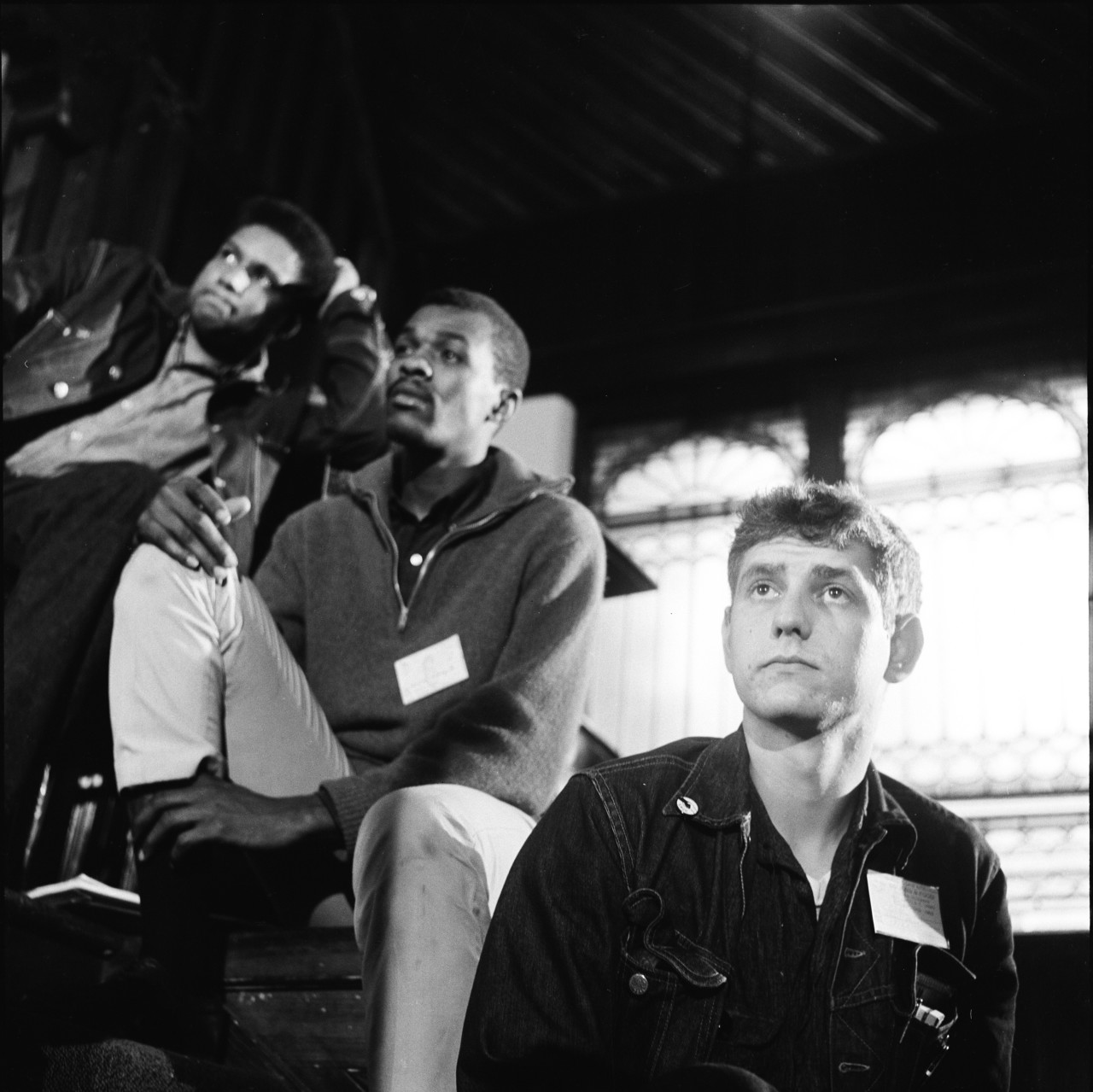

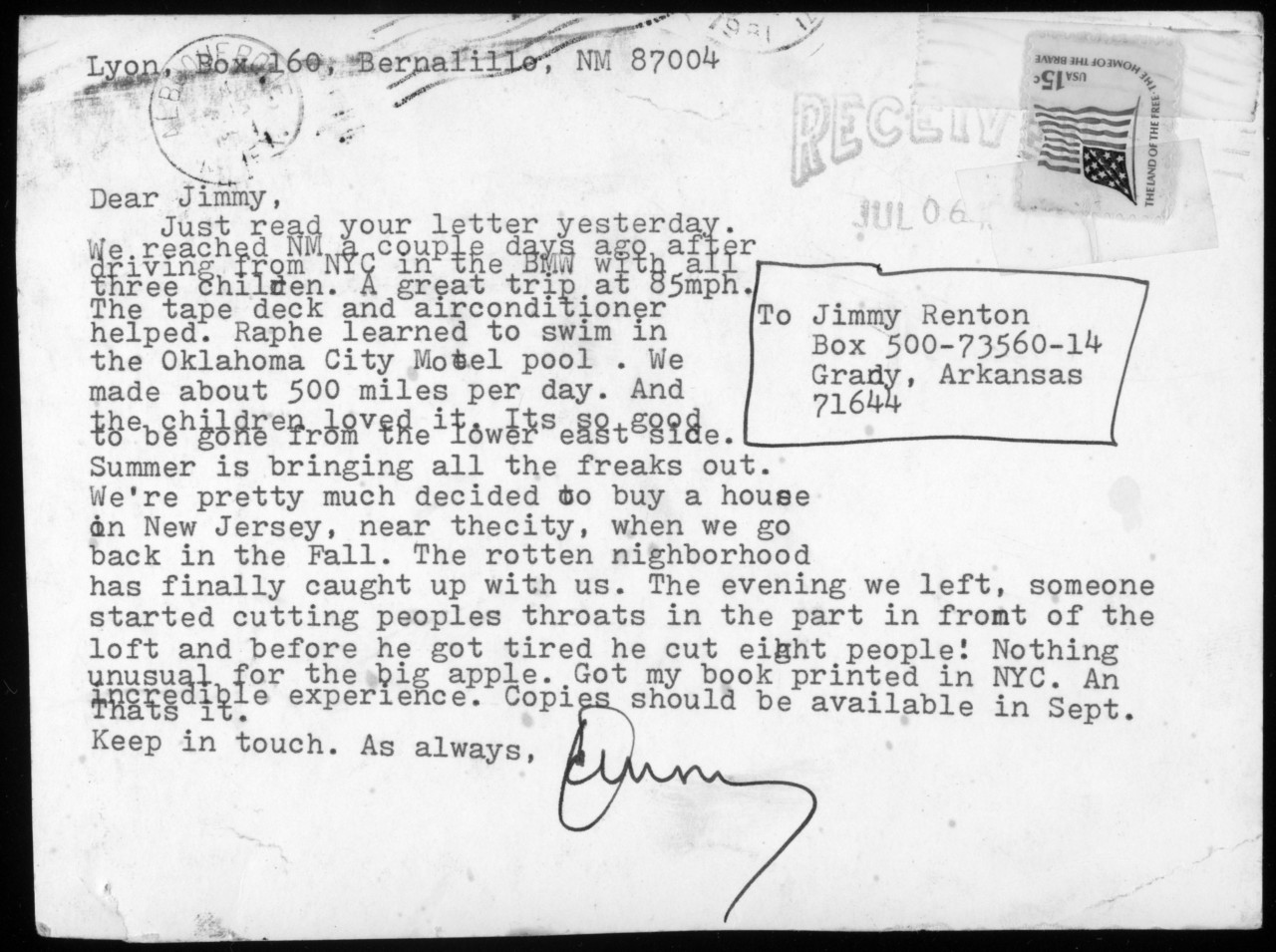

Lyon: At least that long. And it was really a struggle to make this film. First of all, there was the time gap between when the SNCC work happened, the early 1960s, and, let’s say, 2018, when I was beginning to edit the film. It’s two generations later, and I’m going back to try to think about all of this. And then there’s trying to get it into the world. It’s always been hard to get films like mine in front of an audience, but now, in the Netflix era, there’s even more of an expectation of a kind of uniformity in how things are made. As I was finishing the film, the Black Lives Matter movement was happening in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, and I absolutely believed that Netflix would grab this. I believed everyone would see it. I was going to help the revolution. Well, in fact, everyone pissed on this film because it didn’t conform to a certain style. One lawyer said, “Can you make it more like Ken Burns?” And that was the end of her working for me. The film began as a film about John Lewis, who I began visiting and taking footage of about 14 years ago. And then I thought I wanted to expand it and include other SNCC people. But I didn’t want to buy any footage, which is what people do. I thought of all these photographs I had made during the SNCC days. Maybe ten of my civil rights pictures became very, very famous and several dozen were published. But there were another 3,600 that nobody had really ever seen, including me, except on contact sheets.

Kennedy: And you decided you wanted to use them to compose the bulk of the film?

Lyon: Back when I was sitting in those churches and in those meetings in the South, I’d make 36 pictures in a small amount of time, and if I was really excited then two rolls, so 72. And what emerges from that? Maybe one good photograph. Few of the pictures were worthy of being published because I had a very high standard. I’m trying to be a great photographer. Great photographers do not publish mediocre pictures. The other pictures are not great works of art, but together they can make a great film. In sequence, you feel you’re sitting in this church, you’re looking at all these great, young, devoted people, and you get this real sense of being there. Hopefully the film will now emerge from the festival circuit with a distributor. That’s the game plan anyway. I hope a lot of people get to see it. It really takes you back to that time. Nobody tells you about it. There’s no narrator, as such, besides me talking from time to time. You’re placed there as if you were alive then, feeling what was happening.

Kennedy: Do you consider your friendship with John Lewis to be one of the formative relationships of your life?

Lyon: I often wondered what John saw in me. Why me? When he was dying, once I couldn’t call him because Obama was on the phone. And then I couldn’t call him because Nancy Pelosi was visiting him. They were saying goodbye. But you know, when we were young, we were roommates, and when I was sick in the hospital a few years ago, he called me up and said, “You were the best roommate I ever had.” John had a very artistic side. I think he could have been an artist. He loved artists, and he collected work by Black artists. I think he liked the fact that I succeeded as an artist. But can you image two people more unalike than John and myself? I’m about the most unsaintly thing you’ll ever meet. I get in trouble. I smoke pot. John, on the other hand, was like a saint. I think he took on his physical self the kind of punishment he felt America deserved for all the crimes that they had committed against Black people. He was literally covered with scars.

Kennedy: Through all of the collected writings over the years brought together in American Blood, Lewis doesn’t end up being a huge presence. It’s almost as if you were saving him up all these years for this film. It seems like a lucky convergence for the book and film to be out, in a sense, at the same time, because they do a lot of dovetailing. For me, as someone who didn’t really think of you as a writer, or have any idea how much you’d written over the years, there’s really a remarkable consistency of voice over a long period of time. It’s pretty rare in my experience for somebody to be able to put their everyday voice clearly on paper, which you do.

Lyon: I’ve always found writers to be much more interesting company than photographers. If nothing else, I’ve always befriended writers in the hope that they might write about me, which has kind of worked out. And I’ve always loved the act of writing because it just pours out of me, like talking at a party or like how we’re talking right now. But then of course you have to rewrite and edit, and it’s a real punishment, and you have to work with editors. When you do a photo book, nobody tells you what to change. No one says, “Oh, put this picture over there instead.”

Kennedy: In a sense, you’ve told your story through telling other people’s stories for your whole life.

Lyon: A few years ago my wife Nancy said to my son Noah, who is an artist, “Dad’s working on his memoir.” And Noah said, “Again?” I do keep telling the same story over and over. It’s all I know. It was my life. It’s my life now. I’m the most informed about it. And I spent a lot of my life with a lot of different kinds of people — with African-American people in the deep South, with motorcycle gang members, with murderers and prisoners, with Mexicans and illegal people and with other artists. It made my life more interesting. And that’s what’s great about America. There are so many worlds out there. If you take the trouble to leave yours and go into another, you become a much more interesting person. I think that’s what American Blood is about. It is a kind of history of America, told through one life.

Danny Lyon is a frequent blogger at bleakbeauty.com. You can follow him on Instagram at @dannylyonphotos.

For inquiries regarding festival or limited institutional screenings of ‘SNCC’, contact Cody Edison at edison.cody@gmail.com