Déjà Vu in Houston’s Third Ward

Colby Deal — 2020 Magnum nominee—speaks to us about mixing photographic genres, depicting nostalgia for a changing neighborhood, and asserting an artistic voice in defiance of external forces

The above image is available now as part of the Magnum Editions Posters collection. You can explore this new, limited edition collectiom in full on the Magnum Shop, here.

“Ms Shirley is like my third grandma. She’s like that old lady on the block on the street corner that everybody loves and everybody speaks to.”

Colby Deal is telling us about Shirley and Kevin, two of the subjects of his images and residents of his neighborhood — Third Ward in Houston — who have been instrumental in determining Deal’s path into photography.

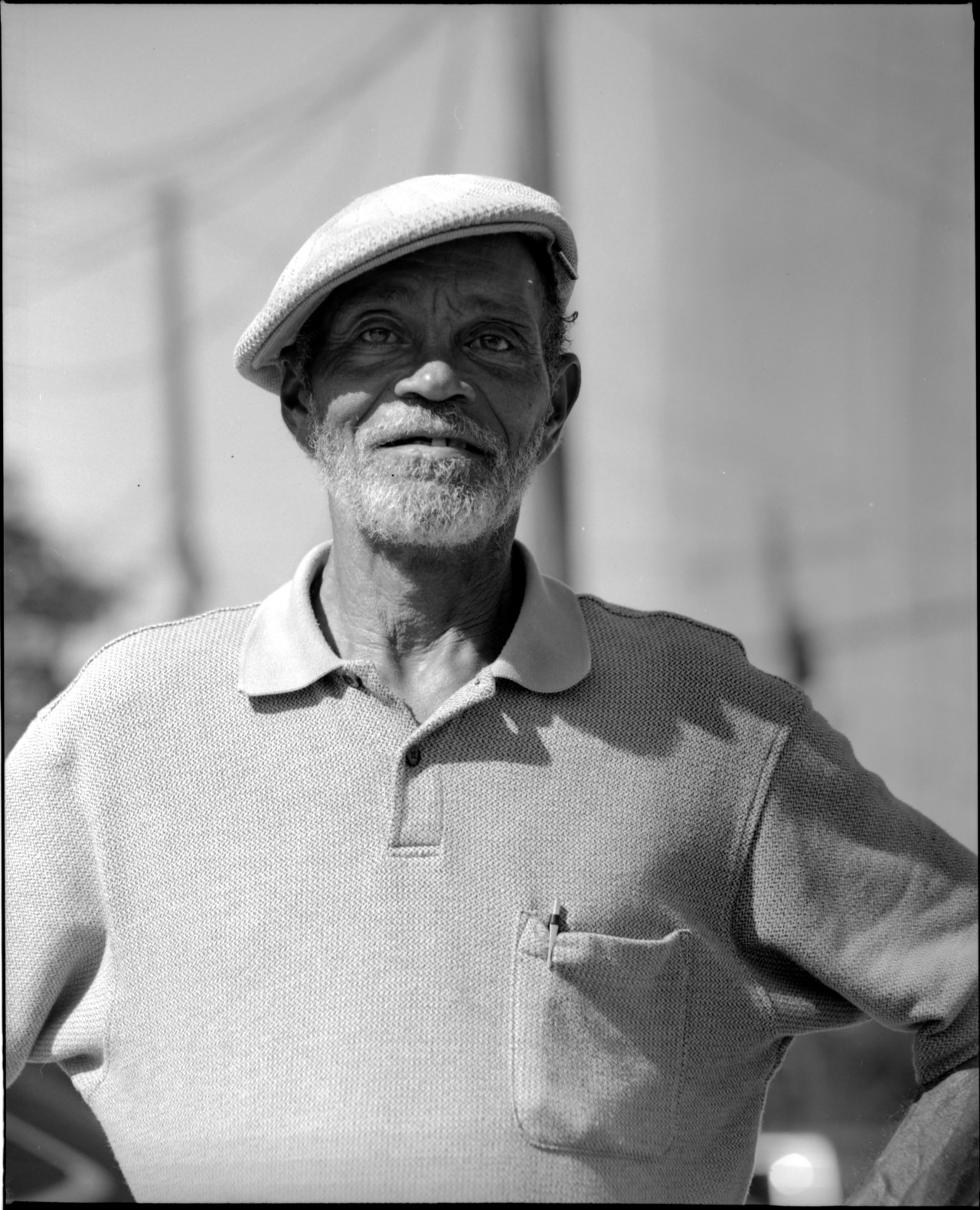

Deal had been walking around with his large format camera when he and Ms Shirley got to talking and he took his first portrait of her. Later that year, Deal was showing her picture as part of his residency at Project Row Houses in Third Ward, an exhibition to which he had invited her and Kevin— “That’s the guy standing in front of the chessboard with the hat”. Deal says that their response to the show helped him to realize that his aspiration was to make art about, and for, others around him. “Just to see their reaction to themselves portrayed in that way in the gallery, and for them to see how many people enjoyed seeing their image — and thought they were beautiful — that was really eye-opening to me. Because you always have that little space of doubt as an artist or creator and it’s like, ‘Am I doing this right?’”

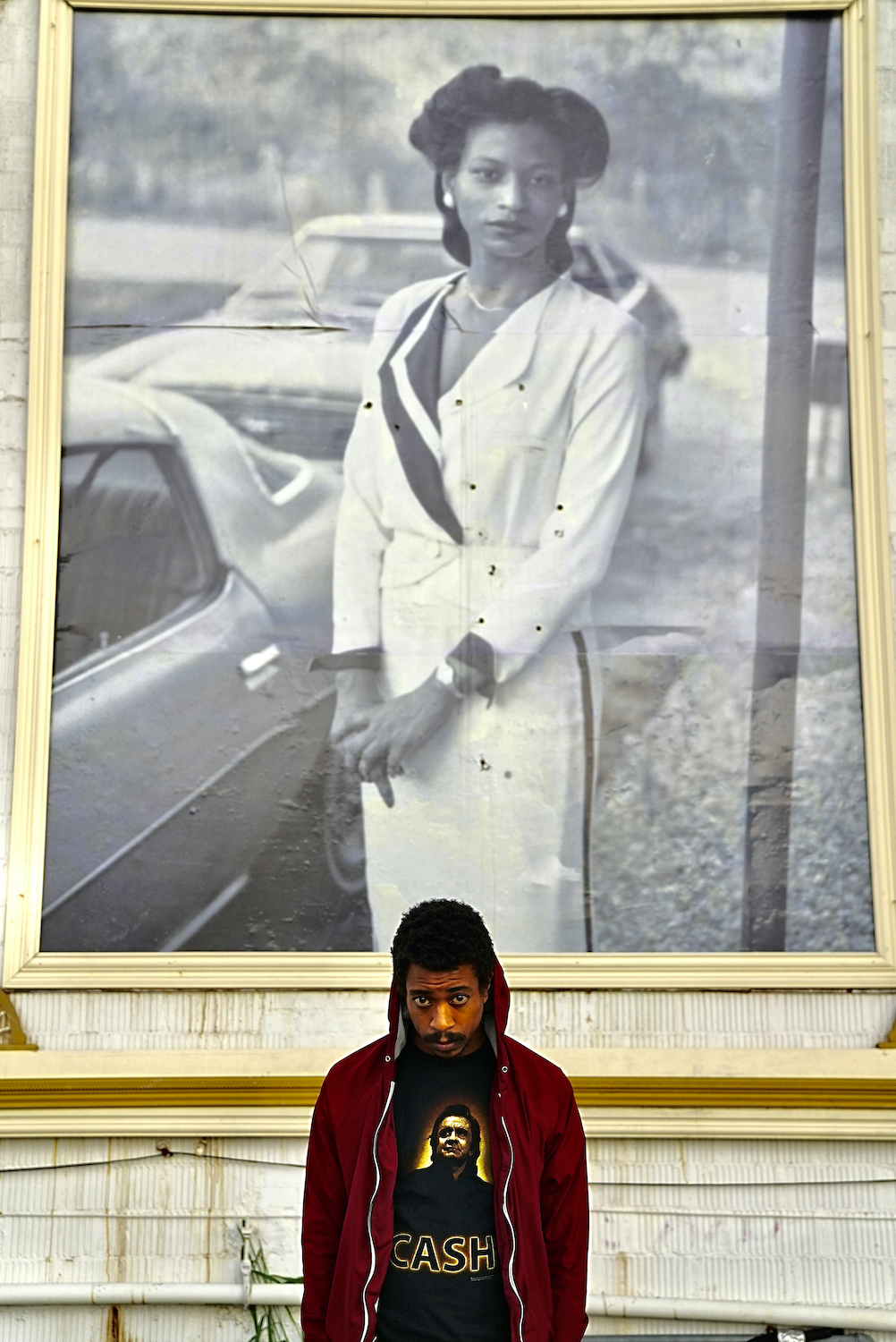

Deal was always artistically-inclined growing up, and usually took on the role of visual documentarian among his friendship groups. He taught himself how to use a camera and developed his artistic voice independently before gaining his photography degree at the University of Houston. Deal’s father’s photography— which captured family get-togethers, weddings, vacations — was another influence: the Magnum nominee would look through his father’s possessions from the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s, and the images he found had a profound effect on him. One of his father’s photographs, a portrait of Deal’s mother, later featured in a fly-posted installation which was recommissioned by Project Row Houses.

Deal’s ongoing project, Beautiful, Still, draws on the romance of past eras to remind viewers of the ephemerality of a neighborhood and community that is rapidly changing; at the same time, it’s a love letter to the lives and the culture that endure there despite multiple detrimental forces.

“People come and they go, memories come and they go, you know, moments come and they go,” Deal says, on the inspirations for his work, “Traditions are being erased. Characteristics are being erased. Buildings are being torn down. Homes are being torn down. Families are being forgotten about and broken apart. The artwork serves as that memory of the original people that were there, that are leaving now or being pushed away.”

"The artwork serves as that memory of the original people that were there"

- Colby Deal

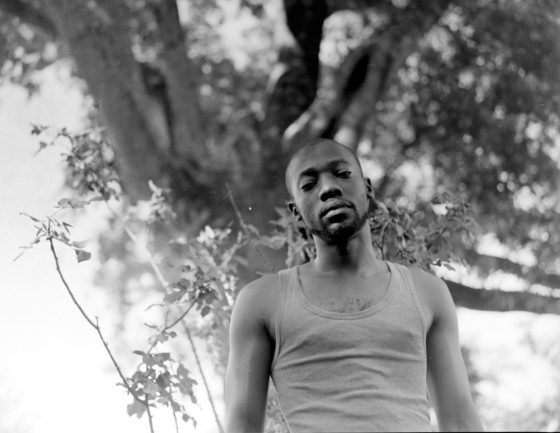

In the project, Deal aims to instill a feeling. One of the techniques he uses to create this is employing motifs from traditional, black, southern American culture in the images. His subjects are seen listening to music, playing chess or dominos, always outside in the front yard or on the street. He takes care to remove identifying symbols like modern cars, brand logos and modern technology like phones from his images, in order to preserve a sense of ambiguity. “I try to put you in this memory. I’m really big on like nostalgia and déjà vu, that vertigo, and those feelings that you get.”

The project is a tapestry of genres: Deal says he likes to preserve the sense of intrigue that comes with variation in mediums. “I look at photography or a project like a plate of food,” Deal tells us, “You want a variety. Ribs are awesome, or mashed potatoes are awesome, you know, but I don’t want a big-ass plate of just mash potatoes or a big-ass plate of just ribs: I want some ribs, I want some potato salad… I want a whole mixture to like make the meal complete. That’s why, when you see me do a project, it’s portraits, it’s candid, it’s street photography. There may be some whimsical stuff in there, to place you in a particular conceptual space.”

"I look at photography or a project like a plate of food. You want a variety."

- Colby Deal

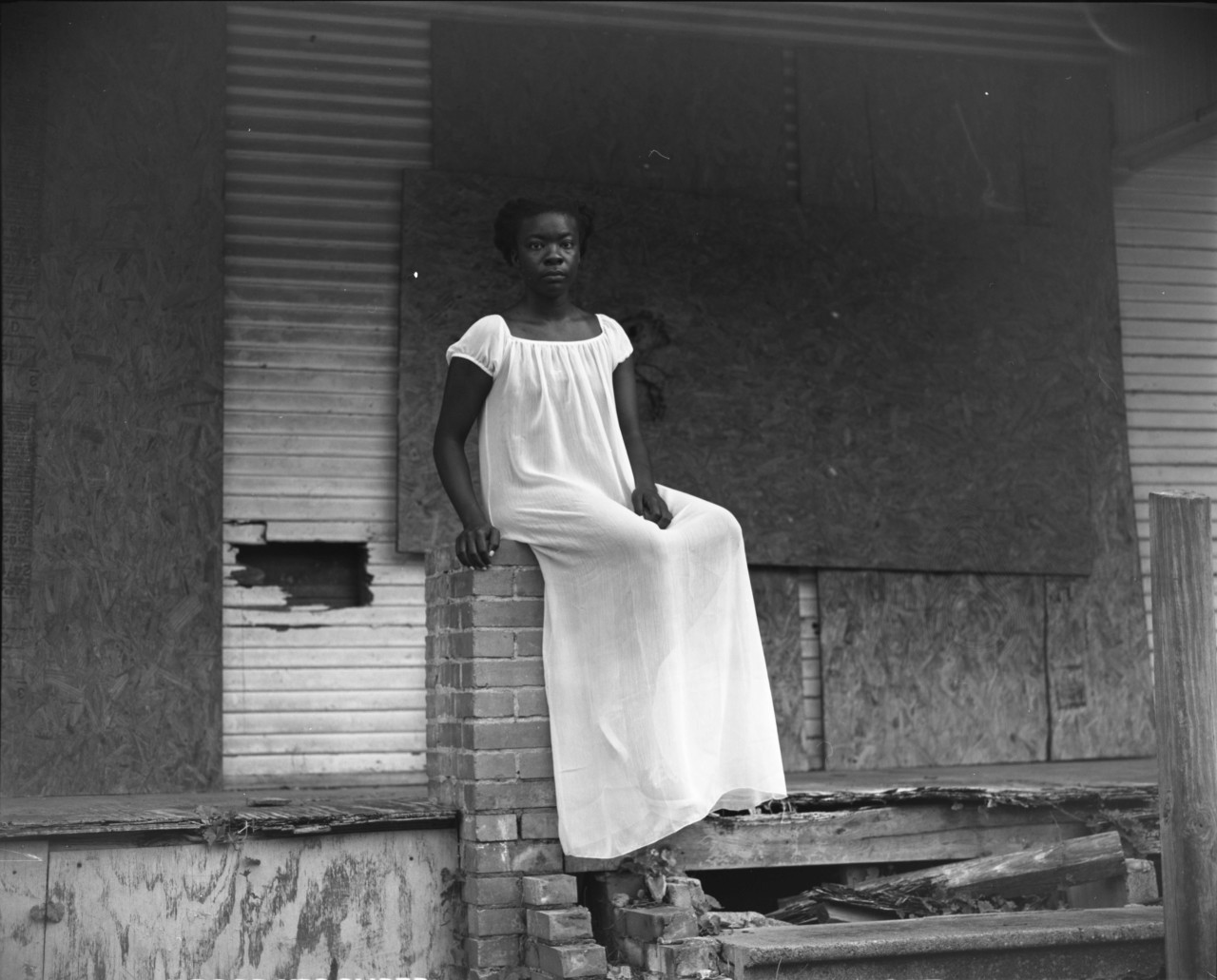

A sub-series of portraits of women in white dresses, the most recognizably staged, feels like an emotional crux in the project. These maternal and sororal figures appear, striking, against a series of decaying backdrops. Deal made these portraits while thinking of the women he has grown up around and come to know, who demonstrate their beauty in defiance of the multitude of social pressures they are exposed to. Deal works quite organically setting up these images, responding intuitively to locations that speak to him. “I wouldn’t tell the subjects what kind of dress to wear, or I wouldn’t look at anything to pick it out,” Deal says, “I just said wear something white, something a little elegant or traditional, because the clothing serves as a vehicle back into a time when things were different.”

"I like being able to put people’s minds back in that time when things were a little bit great"

- Colby Deal

Is there a fixation with the past in his work? “We’re always moving forward, but I don’t necessarily think that everything that we’re progressing towards is always good or beneficial for us,” Deal says, “I feel like our music, our behavior, our manners, the way our families raised their kids 40, 50, 60 years ago—morals were like a little bit more in place back then. Now I just feel like shit’s kind of all over the place.” Yet Deal doesn’t gloss over the violence faced by black people in the USA in the 20th century. Rather than glamorizing that period, he wonders if the difficulty of those political contexts resulted in a respect for certain values. “—as far as the home, the nucleus, the family, and other people, you know. I like being able to put people’s minds back in that time when things were a little bit great,” he says, “now everybody’s kid is buried in a fucking iPad or a phone.”

Deal’s interest in anachronism also plays a part in his preference for material crafts, and the analogue photographic process. “Shooting digital, it’s a computer. When you want to push the button, a signal has to be sent. There’s always a lag in time. There’s always compensation, and fill-ins and stuff. With film, you have to take care of your frames and you have to really see, and really indulge in the moment, and in the people or the environment that you’re around.” Working with his hands to bring his photographic works into large-scale physical form is an important part of his practice. Deal refined his carpentry and material craftsmanship during an artists’ residency in Denver, Colorado. There, he learnt to improve the durability and weatherproofing of his large-scale framed art pieces, which he makes out of everyday decorating materials. This process of building artworks using the most mundane of materials echoes the ethos of his images, drawing out beauty from within what others may deem less worthy of attention.

Deal has been displaying these images around his neighborhood and other parts of Houston; flyposting them with wheat paste largely in disused locations, at sizes of 6ft–16ft tall. It’s an attempt to wrestle back a degree of creative freedom from commercial parties who are increasingly consuming space in the city. He also wanted to sidestep gatekeepers in the arts by taking matters into his own hands. “I was tired of waiting for validation from galleries and museums.” This way of working allowed him to give back to people who he felt were not catered for artistically. “It’s like a cutoff when it comes to under-resourced communities like Third Ward. They don’t feel like they belong, or they don’t feel like they should know about, or see, fine artwork. I’m trying to give a gift, you know, or a thank you, to those same people.” These guerilla interventions have—partly serendipitously— injected life into the area, in a grassroots counterpoint to the gentrification he is speaking about: one poster affixed to the side of a locally-owned café inspired further murals by neighborhood artists, and reinvigorated business for the café-owners.

Deal’s flyposted works stay up for varying lengths of time, decaying slowly on factory walls and street corners in a reflection of the transient aspects of the neighborhood itself, Deal says. Though the images themselves are read timelessly in terms of the ambiguity of the subjects’ costuming and environments, the deterioration of the posters serve as a reminder of the effects of the present moment and of external forces on the subjects. In some cases the posters would last several years, a haunting echo of the short time-frame it can take for gentrification to change the character of a place entirely. Deal chose to utilize the wheat-pasting process to acknowledge these changes, but says it also allowed him to relinquish control over the end product.

Deal relates another story, told to him by Kevin, on gentrification’s cues and indications. “When you live in a neighborhood like this, you see how it looks. He said, ‘When you see a white person walking their dog — be ready. Because soon they’re going to need a dog park. Then they’re going to need a coffee — a little cafe to go to, or a Starbucks.’” Kevin’s fatigue around these stereotypical ‘tells’ belie the process that these events go hand-in-hand with: the displacement and further marginalization of black and poor neighbors.

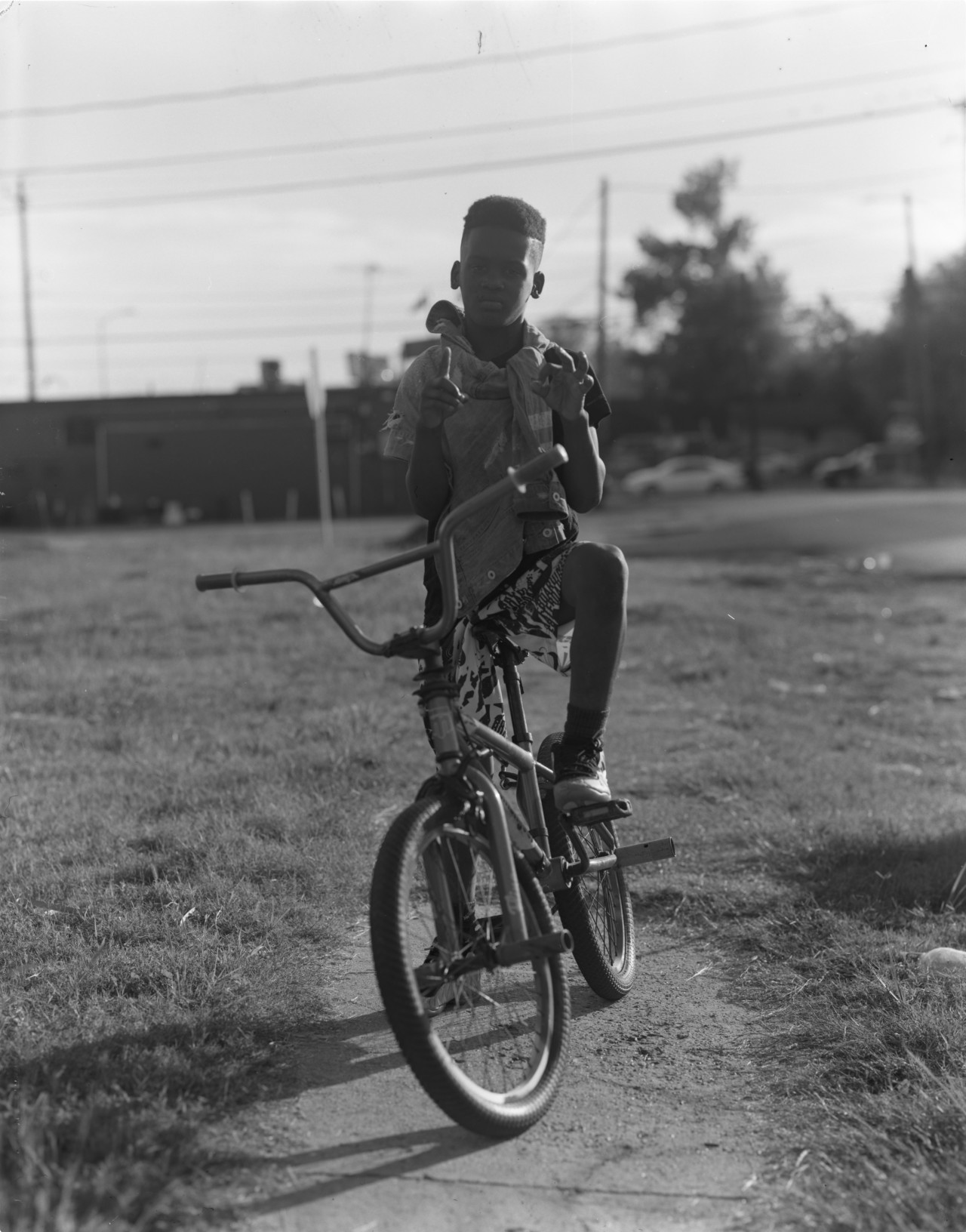

Carrying photographic equipment around has been way into a number of local interactions for Deal. Walking around with his 4×5 camera, in particular, often drew people’s attention. “Especially in the neighborhood where I’m from, it’s not a normal thing,” he says, “It’s usually a caucasian photographer, you know. I guess it was different; people enjoy that aspect, that I was born and raised there. I looked like them and I was documenting and telling their story.” Deal remembers one story about his conspicuousness of his 4×5” camera, involving Little Christian, a boy who stopped his bike right in front of Deal’s lens one day while he was trying to shoot some landscapes.

“He asked me, ‘What are you doing, are you working?’ And I was like, ‘No, this is my homework’, because I was still in school at the time. So he was asking, ‘You do this for homework?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah… so if you stay in school and go to college, you can do this for homework too!’” Deal let Christian take a picture on his camera, and Deal took Christian’s picture in turn. As the boy was leaving, he told Deal that he would be a photographer too one day.

That portrait ended up as one of Deal’s flyposted wall pieces. “Just imagine a little kid unknowingly waking up in the morning to get up and get on the school bus,” Deal says, “and they see themselves portrayed in a positive way. That is like the great psychological effect I want my work to have. I want to create opportunities for self-appreciation, because we’re beat over the head with so many negative images of ourselves.”

George Floyd, whose death in June was one of the triggers of international Black Lives Matter protests, was himself born in Houston’s Third Ward. On the developments that the year 2020 brought to understandings of race and justice in America, and the influence on his practice that that had, Deal conceives of Floyd’s death as one which — in some ways — was not significant beyond the visceral response it prompted. “I’m always looking over my shoulder. We always are, because of our skin color. So we have no choice,” says Deal, “With police brutality, and the disregard for life for people of color here, now my eyes are even sharper. My mind is even sharper on watching my back, where I go, how I go. I even pay attention to how I hold my cameras.”

But the mass response that Floyd received marked a watershed in a country where black and brown men have been killed by police in the public eye for years. It gives Deal hope, because it means racists and white supremacists no longer have the complete free reign that they previously did. “I walk a little taller, you know,” he says, “I walk a little stiffer because I know that they’re scared.” Deal continues, “I feel like this marks the red generation, of people who are angry, people who are tired of black people being killed daily. They are not only being killed by police officers, and explicitly-racist white men, it’s also Covid-19 and influences of people like Donald Trump.”

Deal explores these themes in a series he made this year, which recently exhibited at the Houston Museum of African-American Art. The project’s title, Red Gen, alludes to a demographic of people Deal feels have been stirred up by the radical energy of the present moment, and are preparing to cause what he describes as “good trouble”. Through a series of portraits, the project documented ordinary people who have affected change in their communities in the wake of this summer’s uprisings in America, whose work spans a broad spectrum: from doctors, to realtors, to farmers. It recognizes that you don’t have to be an activist to be an activist — to be able to make a difference within the spheres of power you have. “You’re doing your part. It’s many levels, you know,” says Deal, “You don’t just have to go out and run out there with a grenade and blow something up. It’s many ways to induce change, I feel.”