Eli Reed’s Formative Years

The Magnum photographer reflects on his artistic beginnings and shares the stories behind some of his earliest images

“I was the good kid, always reading, painting, quiet, never getting in trouble,” Eli Reed says of his early years. Born in 1946 in Linden, New Jersey, Reed was aged 4 or 5 when he moved with his family to Perth Amboy, a few miles south, as a result of a fire that destroyed their home. When his mother died, the family moved again: Reed, his father, and two brothers went to live in the John J. Delaney Homes, a low-income housing project on the outskirts of the city. The industrial brick buildings of the Delaney Homes, built in the 1950s and since demolished, were once home to 252 families including Reed’s friends: Bruce Taylor, who became a defensive back for the 49ers and his brother Brian, a player for the New Jersey Nets. Reed grew up playing stickball with local kids, many of whom were tagged as troublemakers from a young age. “All the tough guys were my friends because I respected them as other people. Stickball was the connecting cord.”

As an adult, Reed would discover that Perth Amboy had long been a site of resistance, dating back to its time as one of the stops on the Underground Railroad, a secret network of routes and safehouses used by enslaved African-Americans to escape northward into free states and Canada (or south out of the United States altogether) during the 19th century. “In the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan tried to incorporate themselves into Perth Amboy and they were kicked out, literally,” Reed says. “They made another attempt and they were greeted by six thousand Perth Amboyans, who drove them out — which made me feel pretty good. I saw Perth Amboy as a decent place and not as bad as what was going on in other parts of the country, such as the South. It was a good place to grow up.”

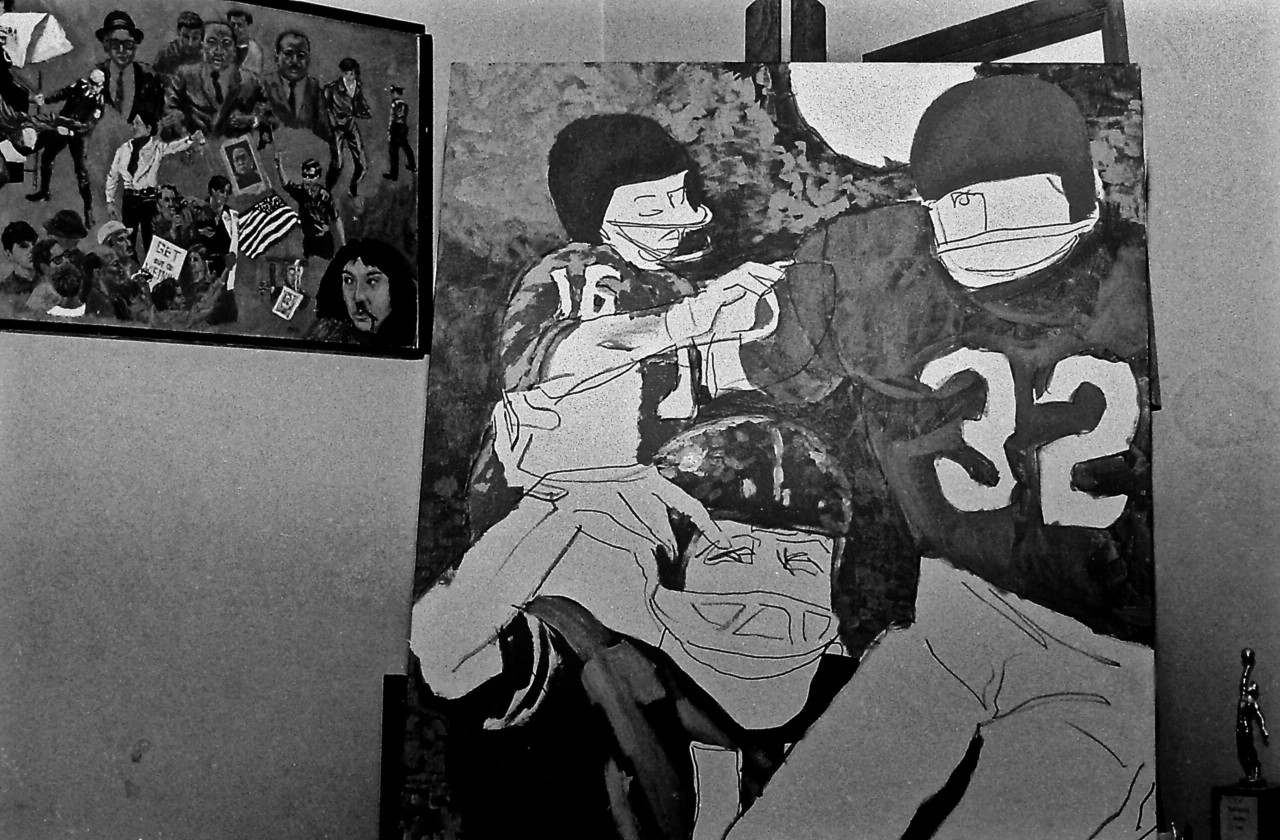

Reed made his first photograph – of his mother standing in front of their Christmas tree – at the age of ten. Two years later, she passed away and the photograph became a vessel to hold Reed’s memories of life, love, and loss and a means of connecting the present and the past. He became interested in art after entering high school. “Looking at paintings of historical events, that’s probably what seduced me,” Reed says. “Perth Amboy High School was actually pretty good; they didn’t look down on you because you were black. The teachers were very supportive.”

When Reed was a sophomore, he was called into the principal’s office where he met an internationally-known New York art critic who had seen one of his first paintings at a local exhibition in front of the high school. As Paul Theroux writes in Eli Reed: A Long Walk Home, “Eli had done a view from inside the kitchen of his apartment in Delaney Homes. The angle fascinated the critic, and the kitchen in the foreground was the least of it: the view showed the kitchen door open to the outside, leading the eye out and beyond to the open air, and a hopeful or at least more promising background. “I was still thinking I was in some kind of trouble because I lived in the Delaney Homes housing project. […] I remember his talking to me, and my looking at my oil painting, as if it were the first time. The funny thing was that I was wondering what he was doing in Perth Amboy.”

“You should consider a career in art,” the man said to him, in the presence of Eli’s proud principal and other adults in the office. That was just the kind of support Reed needed to propel himself. After graduating, he enrolled as a night school student at the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Arts, supporting himself by working full time as a nurse-orderly at Perth Amboy General Hospital and later St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village.

Reed began studying photography through sheer happenstance. While taking a course on illustration, he was assigned with creating a swipe file: a collection of pictures to use as research and reference for whatever drawing or painting he would be working on. He began spending time poring over photo annuals and magazines like Popular Photography, Modern Photography, Camera 35, and Twen. “The pictures that stood out always had Magnum behind [them],” Reed says. “I started to think about what it would be like being there. Witnessing things close up, in the way those photographers did.”

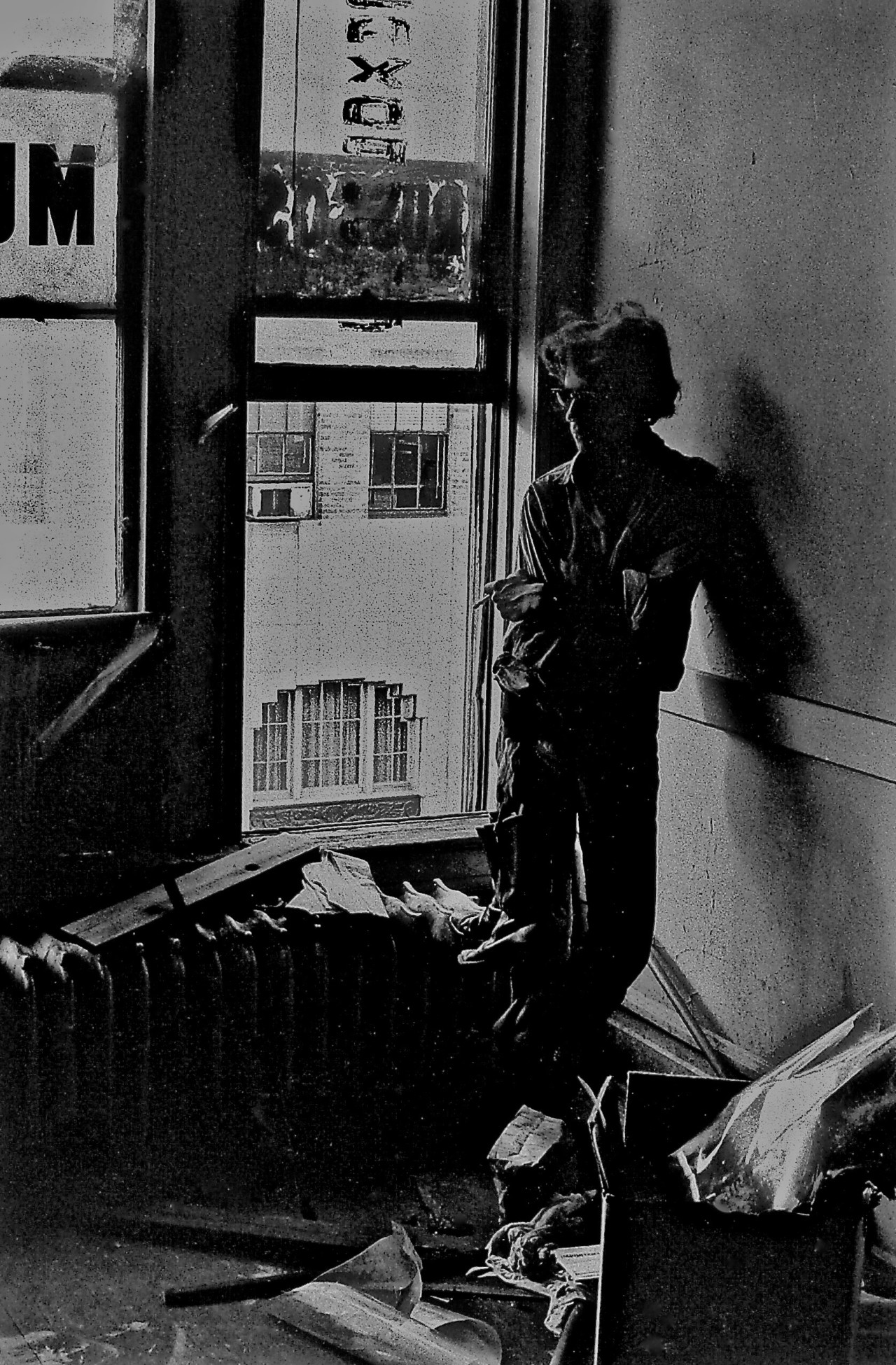

In his final year at art school, Reed took a course in photography. He went home and set up a darkroom in the closet where his father kept his jackets. “It was tight and I could be in there for five hours with small trays. It was a lesson and I was soaking it up as much as I could,” Reed says. “I had always done a lot of reading of everything I could get my hands on, well beyond the stuff you got fed in high school. I remember fellow art school students called me ‘The Intellectual’ because I was always reading, drawing, and painting.”

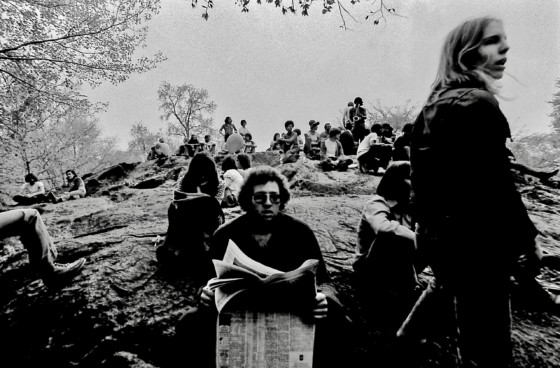

After graduating in 1969, Reed did a five-month stint at a New York advertising agency and quickly realized he wasn’t destined for office work. He began carrying a camera everywhere, taking pictures as he moved about his daily life. In 1970, he volunteered to work in the illustration department of a rock & roll magazine, Zygote. Although Reed only had four photographs in his portfolio, they started sending him on photo assignments.

The first of these brought him to a center of black life, history, and culture — Harlem, New York — to the Apollo Theater to cover a concert put on by the Young Lords, a civil rights group dedicated the empowerment of Puerto Rican and Latinx communities. “I still lived in New Jersey and hardly knew where Harlem was,” Reed recalls. “I went into the Apollo and there was a woman introducing everyone. She was very serious and intense. At one point, after she introduced somebody, she said, ‘They’re telling me in the back I should tell some jokes. Well I don’t know any jokes.’ The concert started at midnight and I was there until five in the morning.”

With that first assignment, Reed knew exactly what he wanted to do: to be there and make photos. That same year, Reed met his mentor, Donald Greenhaus, at a bus stop while on his way to the Port Authority Bus Terminal. Greenhaus noticed Reed was carrying an armful of contact sheets and struck up a conversation about photography. Although Greenhaus was only five years older than Reed, he had already established himself as a photographer with images of his childhood friend turned rock star, Lou Reed, and his band the Velvet Underground.

“Donald was the first photographer I met who was doing things I wanted to do. I became his first real student,” Reed says. “I was working at St. Vincent’s and would get off at 7:00 am and walk over to his studio in Soho. That was the beginning of my education in photography. I met all kinds of interesting people like Alan Vega [a visual artist and musician in the band Suicide]. It was the first time I realized [the truth of the principle,] ‘nothing ventured, nothing gained’.”

Reed subscribed to that philosophy and set to work right away. He soon met Reginald McGee, who was working with James Van Der Zee on the 1969 exhibition Harlem on My Mind at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, along with another black photographer, Jerry Tucker, who offered support. Reed remembers, “He said, ‘You could probably become a good working photojournalist.’ That’s the first time anyone said that to me.”

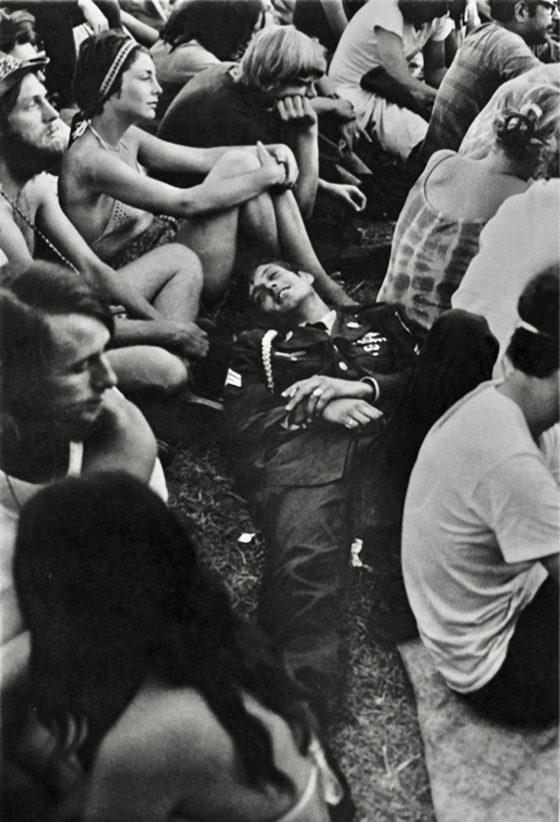

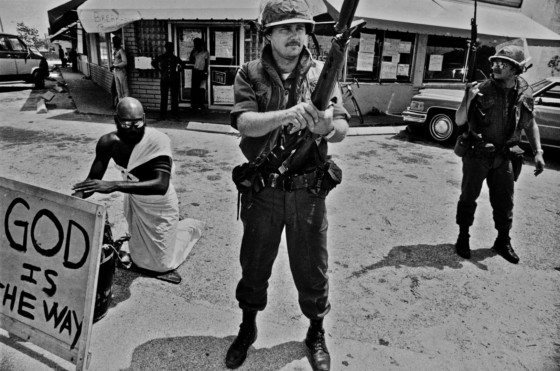

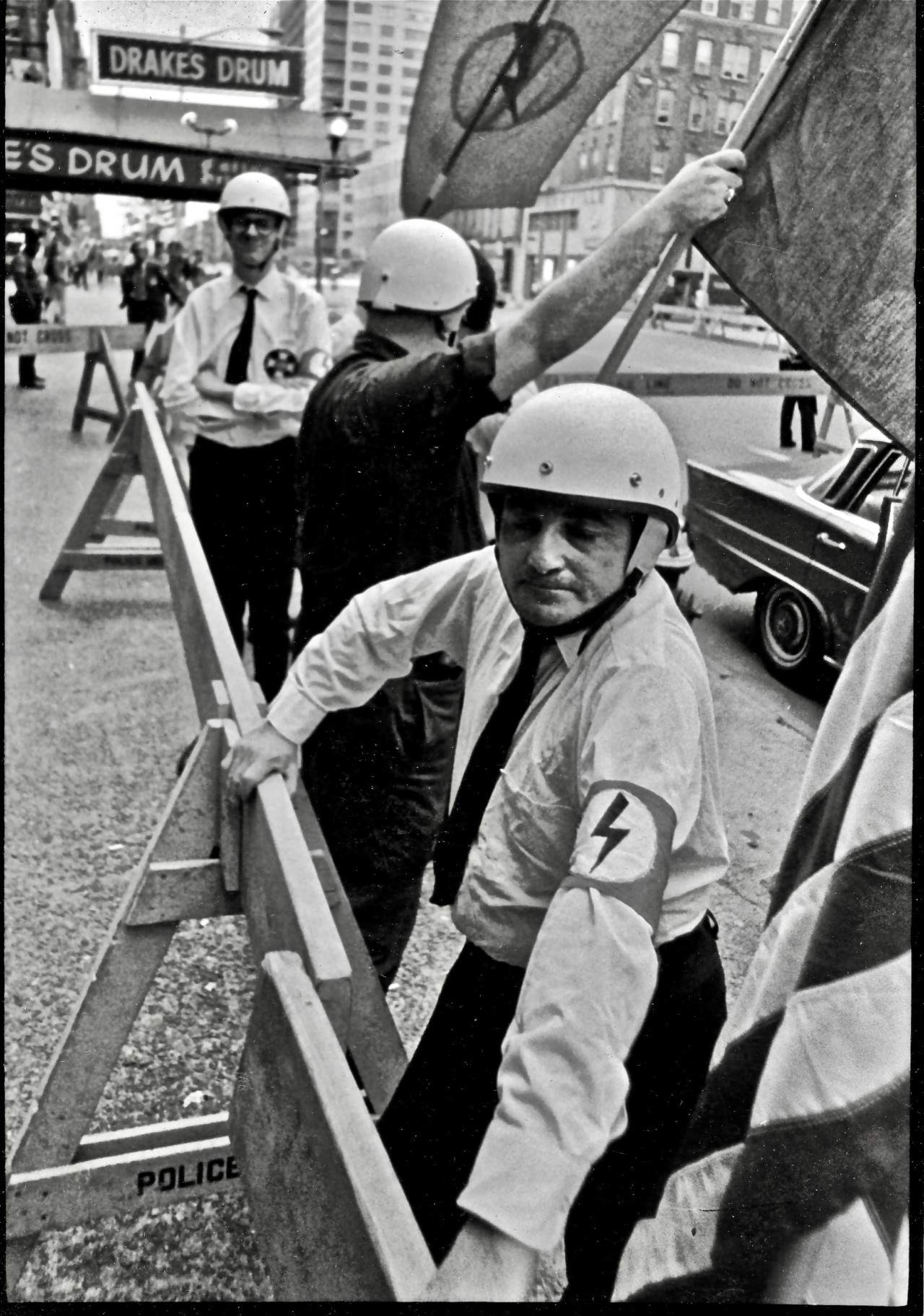

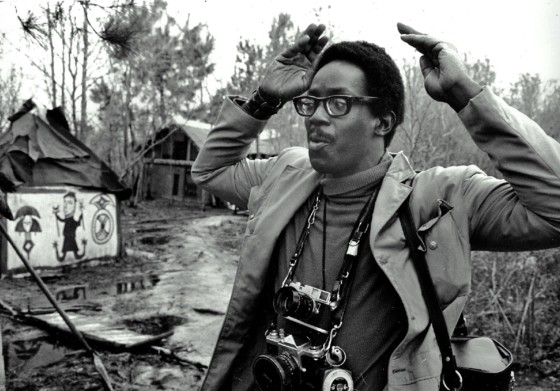

Reed recalls the pressures, in those early years of pursuing his photographic ambitions while earning a living via his full-time nursing job. He directs us to some photographs he made of attendees of the Atlanta Pop Music Festival in Byron, Georgia— another early assignment he shot for Zygote. “I was not paid for photographing for the magazine because I wanted to get more professional experience as a photographer,” he says. “It was my second trip to Georgia within a month covering the music scene while working as a hospital nursing orderly at Perth Amboy General Hospital. The nursing supervisor was kind enough to allow me to do this work and make up the time after getting back to Perth Amboy so I still could be paid my salary.” A job covering a neo-Nazi demonstration in the early ‘70s, for weekly newspaper Our Town, went similarly unpaid.

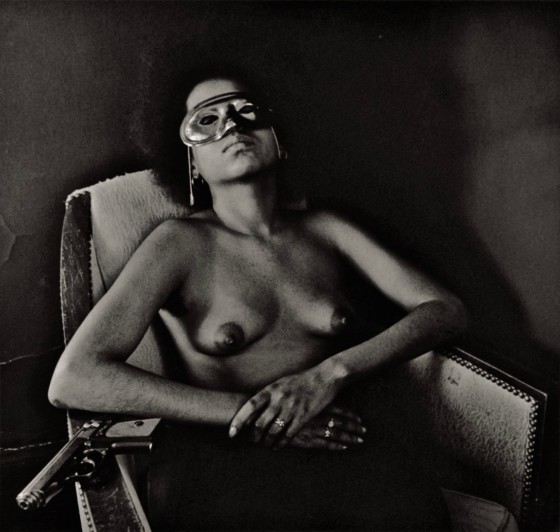

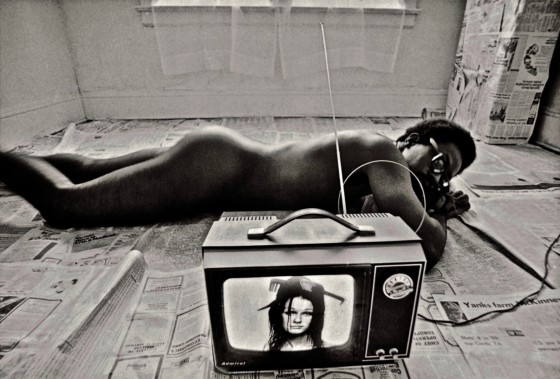

Alongside documentary work, Reed also pursued projects of a more experimental nature during the 1970s. His project, ‘The Whole Sick Crew’, was a photo essay combining portraits with more traditional photojournalistic methods. “This photo is about the power that some woman have in certain ways,” he says, of his nude portrait of a woman, “But really it’s about how people learn from the environment they are raised in and the various other ways people are influenced in the things that they do in their lives.” Another image from around 1970, a self-portrait, explores “the inner self of how one deals with the world that we are exposed to daily and how it affects us.”

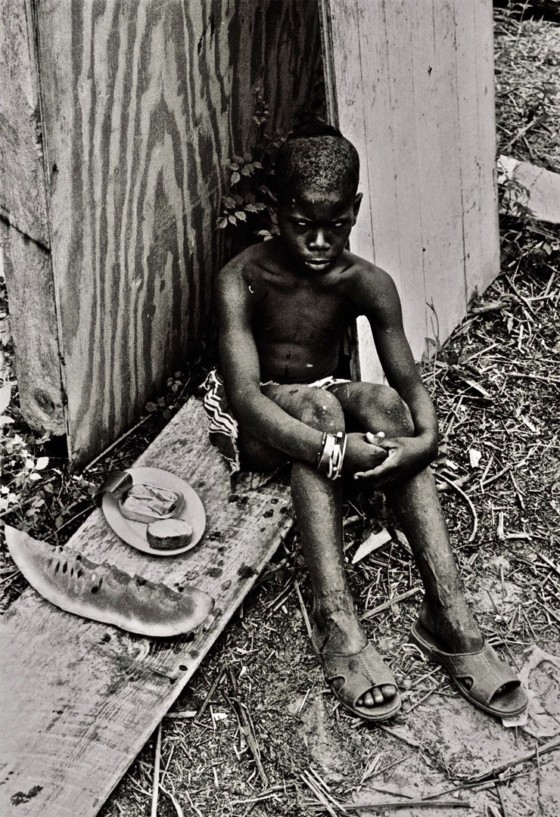

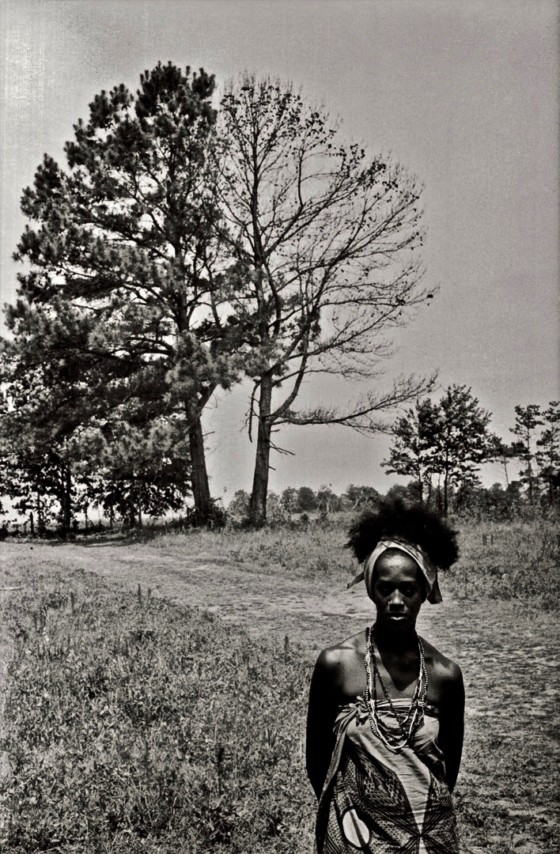

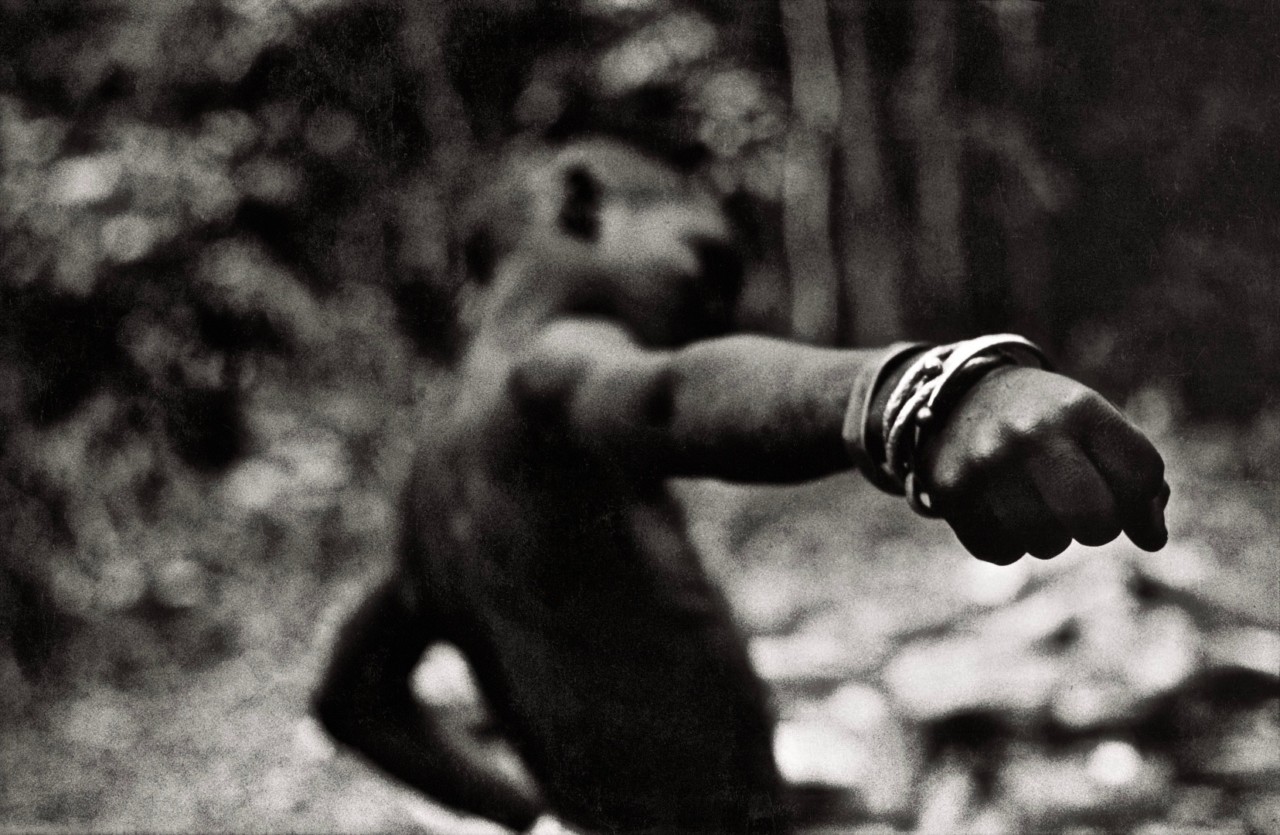

Reed had been a keen practitioner of judo since 1965, a martial art whose combined offerings of physical and spiritual training, the photographer says, became a religion to him. At one of these classes he met a friend and fellow photographer Les Wormack. Together, they embarked on a road trip and photographic project to document a village in South Carolina named Oyotunji. Established by African-American emigres from New York in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement, the village’s life and running was based on the customs of a traditional West African village. Oyotunji still exists today, though with fewer residents now than the 200-plus of its peak in the 1970s.

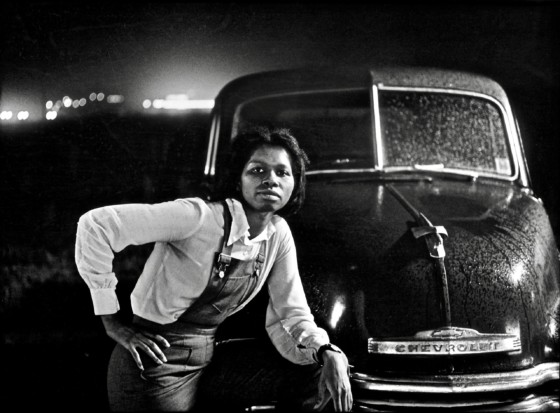

“My then future wife (unfortunately it did not work out), Ginger, heard about this African village project I was doing with Les and she was curious about it,” says Reed. He refers to another image from his archives, of a young woman resting against the hood of an old Chevrolet. “I made this photo during the drive from New Jersey to South Carolina,” he recalls, “We picked her up in Washington, D.C. on the way down.”

Magnum photographer Leonard Freed had published a seminal monograph in 1968, Black in White America, which became a touchstone in Reed’s life. “It was so intelligent, so honest, and there were no clichés in there. There was the reality he was covering and I really get emotional about that,” he says. “Van Der Zee documented his community. Well, I wanted to document a bigger community, meaning as much as I could cover. I had hoped to do every state but then I realized, without the money, there’s no way you could do that. But I wanted to get a sense of Black America: the good, the bad, the graceful, the ungraceful — the people.”

In 1997, W.W. Norton published Reed’s second book, Black in America. (His first, Beirut, City of Regrets, released by the same publisher, documented civil war in Lebanon in the aftermath of the 1982 Israeli occupation). A powerful portrait of late-20th century life made over a period of two decades, Black in America depicted Reed’s travels across the nation, capturing moments of tragedy and triumph, as well as quiet scenes filled with the tender intimacies of daily life. “The book came about because of on-going witnessing things and going with my gut, not trying to go with a preconceived notion,” Reed says.

The work was also inspired by Reed’s exposure to Kamoinge, an all-black photography group founded in Harlem in 1963, which has since become the longest-running non-profit photography collective in the world. Founded at a time when few black photographers were shown in galleries and museums, or got commissions from mainstream publications or advertising agencies, the members of Kamoinge were determined to make work about black life unfettered by the white gaze.

Though they are only now receiving their proper due in 2020 with the landmark touring museum exhibition, Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoinge Workshop, their work did not go unnoticed at the time. Reed remembers reading a magazine article about Roy DeCarava, the group’s director, and seeing something about Kamoinge in the piece. “I really admired these guys and what they were doing,” Reed says. “I heard about Kamoinge before I heard about Magnum. There was always awareness and admiration for the work I was seeing. They really were so important in a lot of ways. You try not to get what’s expected but what is really there. In so many ways I owe a lot to Kamoinge for always being there, in my ear.”

In 2001, Reed came full circle and joined Kamoinge. “Kamoinge and Magnum share places in my heart,” he says. “It’s the way it should be and the way it will always be because so much goodness has come out of the craziness. You do good work and it will come to some use some place. It comes down to, what’s a good picture? A good picture is a picture you can’t get out of your mind.”