Making the Image: Elliott Erwitt’s Bulldog in New York

The photographer recalls borrowing a camera to capture the surreal situation before him

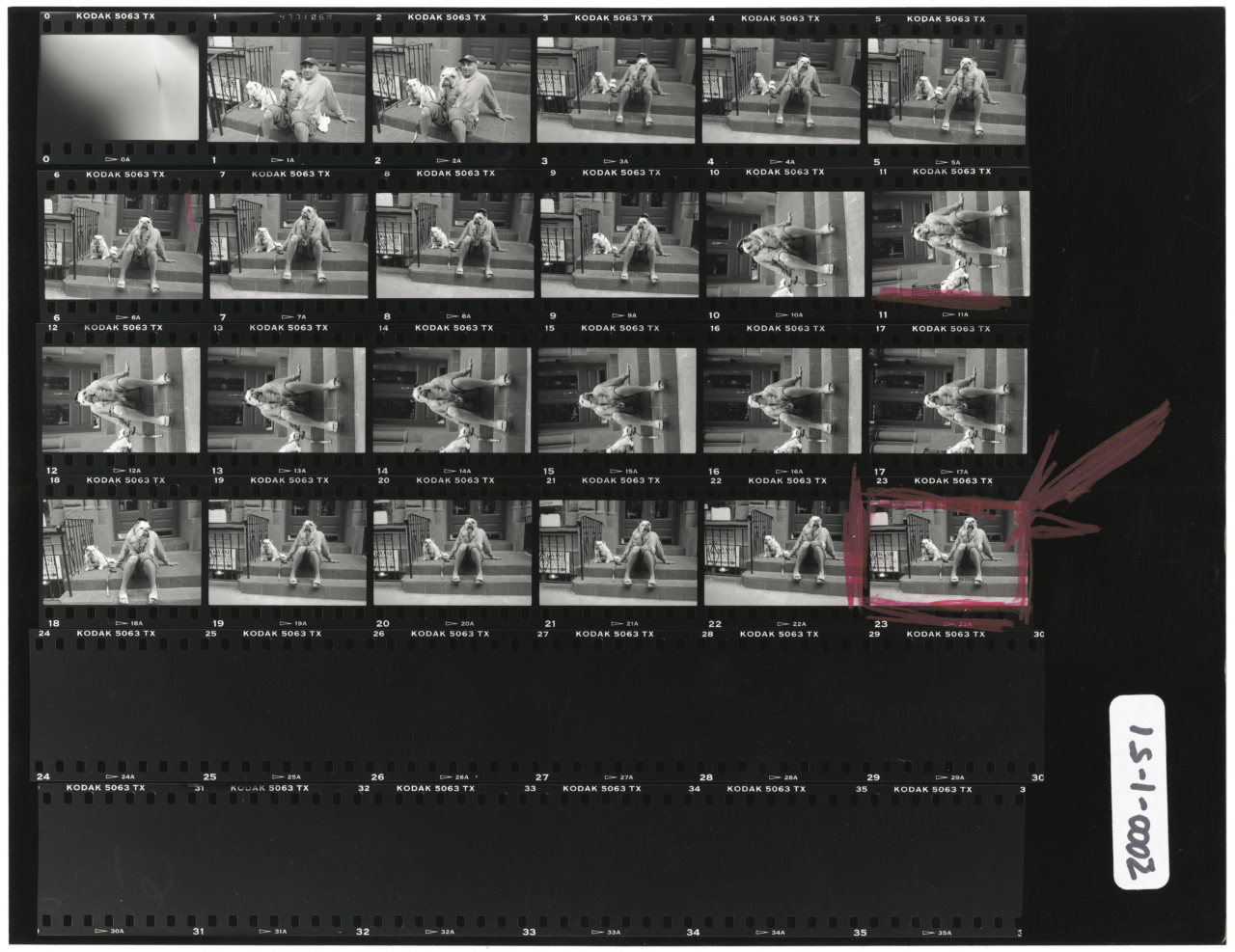

Contact sheets: direct prints of sequences of negatives were – in the pre-digital era – key for photographers to be able to see what they had captured on their rolls of film. They formed a central part of editing and indexing practices, and in themselves became revealing of photographers’ approaches: the subtle refinements of the frame, lighting and subject from photograph to photograph, tracing the image-maker’s progress toward the final composition that they ultimately saw as their best. There is a voyeuristic aspect to looking at a contact sheet also: one can retrace the photographer’s movements through time and space, tracking their eye’s smallest twitches from left to right as their attention is drawn. It is as if one were inside their head, offered a privileged view through their very eyes from the front row of their brain.

As Kristen Lubben wrote in her introduction to the book, Magnum Contact Sheets, first published in 2011 by Thames and Hudson:

“Unique to each photographer’s approach, the contact is a record of how an image was constructed. Was it a set-up, or a serendipitous encounter? Did the photographer notice a scene with potential and diligently work it through to arrive at a successful image, or was the fabled ‘decisive moment’ at play? The contact sheet, now rendered obsolete by digital photography, embodies much of the appeal of photography itself: the sense of time unfolding, a durable trace of movement through space, an apparent authentication of photography’s claims to transparent representation of reality.”

Here, we look at the making of Elliott Erwitt‘s famed photograph of a bulldog on a New York City stoop.

Elliott Erwitt’s comical photograph of the bulldog sitting on its owner’s lap exemplifies the adage that dogs really do look like their owners. Well known for his dog images, Erwitt captures the precise moment when, framed by the stoop of a New York City building, the head and body of the dog are in perfect alignment with the arms and legs of its owner. Somewhat fantastical, the superimposed head highlights what Erwitt calls the ‘visual contradictions that are a photographer’s dream’.

As Erwitt recounts: ‘I was out walking with my friend Hiroji [Kubota] around the corner from my studio on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and I didn’t have my camera. I saw the situation and I said, “Could I borrow your camera?” And I borrowed his Leica. He was very generous and let me use it and I shot the whole roll of film on it.’

By the very last picture on the roll, all the compositional and conceptual elements are in place, the absurdity of the image further supported by a second dog on the left sitting in exactly the same pose as the surreal dog-man composite. The contact shows Erwitt’s patience, shooting around an image methodically until he has all the elements synchronized for maximum effect. As he says, ‘It’s a lot of pictures getting to the good one.’