Encounters of the Archive Kind: Histories of Somalia and its Diaspora

The stories remembered, and lineages traced, by a community are determined by how and why we collect photographic records of it

As part of Magnum Photos’ recent Emerging Writers in Residence program, six early-career photography writers were invited to research and respond to a topic of their choosing in Magnum’s photographic archive. This text is one of the works that were produced on the residency — see all six at the link here.

Abira Hussein is a Doctoral Researcher in the Information Studies Department at UCL. In this text, she reflects on the imaging of Somalia and Somali people via the photographic archive, analysing a range of materials: from items within Magnum’s database, to ethnographic images, to family photographs within personal collections. In this discussion on the ways visual records and their classification shape how the past is imagined, Hussein poses questions about how the archive can serve to disconnect or reconnect a community with knowledge of itself.

When I am faced with the task of interpreting an archive as an outsider, adjacent to an organisation and its machinations, it always creates resistance. I’m not quite sure what’s going on and why, but I try to persist and lend my histories and lens to the sentry as I am let into the hallowed site that is the archive.

Well, what is an ‘archive’? I have often heard it to be described as flat documents, such as photographs, letters, ledgers, but also audio and visual material. How do we decide when something becomes an archive? In Stuart Hall’s paper, ‘Constituting an Archive’, he speaks about a loss of innocence, a somewhat objective look at the materials, and a filtering. It’s not an arbitrary process, but a dynamic and responsive one. For many, it conjures the past, a systematic, linear recollection. I have always seen it as so much broader than the discipline permits: more permeable, fluid, and boundless. These acid-free boxes and stacks are supposed to belie all of our histories, but in its construction, its rigidity, so much is lost and violently excluded. Its design and foundation are about orchestrating knowledge to wield and maintain power, an instrument of control, not liberation or expression. Yet as a diaspora living away from the places where I learn myself, I’m untethered and these institutions, recognised as vestibules of history, are all I am told I must anchor to.

Do archives require residency in the academy, or in institutions, to have value and be remembered? How have archives in these spaces traditionally transmitted our histories? And therefore, what knowledge is produced from these spaces? Jacques Derrida notes the contingent nature of archives, and anything that falls outside of those parameters is often seen as not worthy to collect. Paul Otlet describes archives as being anything that conveys information: a book, an object, a sound; and argues that digitisation has further eroded those distinctions. These questions are often circulating in my mind when I encounter archives online: how do they organise the information, how are things tagged, what will I find, what is missing?

The Magnum archive is a collection of their photographers’ commercial work. In looking through its database of photographs, it’s not always clear under what circumstances they were taken or who the individuals in the frame are. I started my search with the keyword Somali; this led to a result of 859 images. I use generic and broad terms as we are often not afforded specificity. Search categories are limited. The terms I can use to find images that relate to Somalia are restricted to geography, and things that have happened to us rather than about us.

I come into contact with tired stereotypes depicting famine, war, migration, buildings that were once intact, now bullet-ridden, AK-47s, the bright dresses we know as Baati changed to abayas and jilbabs. I witness this evolution. Does the trauma repeat? Can I feel it second-hand? It’s not obvious why things have changed. I use dates as my guide, filling in the gaps from what I already know of Somalia’s timeline.

I continue to flick through, recognising landmarks, the dictator Siad Barre, his presence that casts a long shadow, women, farming, children playing… and then, just like TV interference, I suddenly notice images of animal carcasses, distended abdomens, distress, corpses of children wrapped in cloth. It feels like whiplash. I am violently thrusted forward into the reality of passive victims, depicted without agency, helpless against nature, devoid of context. Photography is instrumentalised as a tool of colonialism.

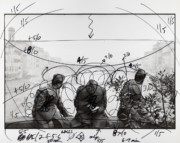

Amongst the sea of images, I was drawn to photographs of everyday life such as those taken in 1980 by Chris Steele Perkins: moments that were captured in the backdrop of unrest or hardship during the Ogaden war, routine activities. Mark Sealy’s ongoing project Reimagining African Political History through the Magnum archive speaks about the power of banal images that depict everyday moments. The power lies in relocating them outside the realm of the colonial lens: no longer icons of famine or victims of war, but of individuals with a past and future beyond the photograph.

In 2015 I was part of a collective of artists and researchers that were responding to Autograph’s The Missing Chapter project which explored the visual representation of Black and Asian individuals in 19th and 20th century Britain. These collections of images sourced from private, public and personal archives held a single staged photograph of a Somali group in Crystal Palace taken in 1895. It was a reminder of a common practice in the Victorian period where imperial subjects from around the British colonies were exhibited as live dioramas, as objects of curiosity. I was reminded of that as I looked through the Magnum archive.

How do we respond to ethnographic images? What entanglements do they create with the imagination of our past and the places where the Empire was orchestrated? How has that legacy continued in photography ‘post-colonialism’?

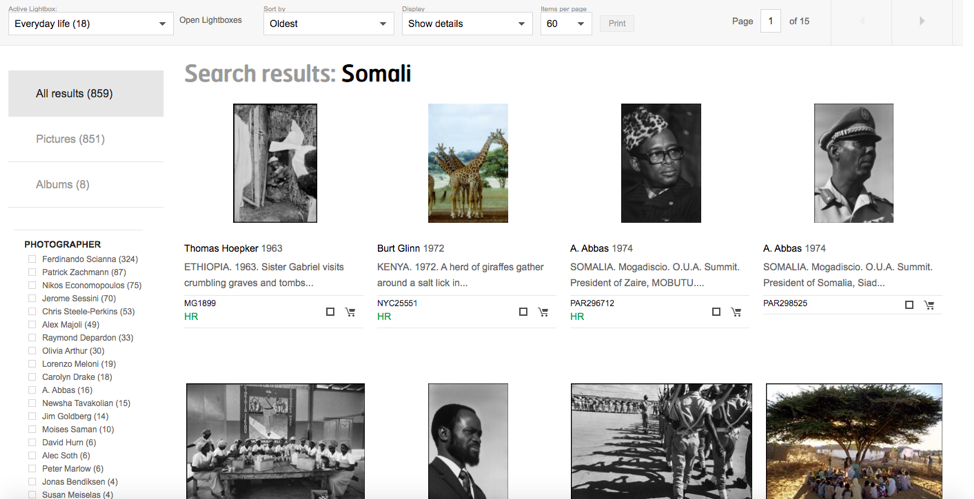

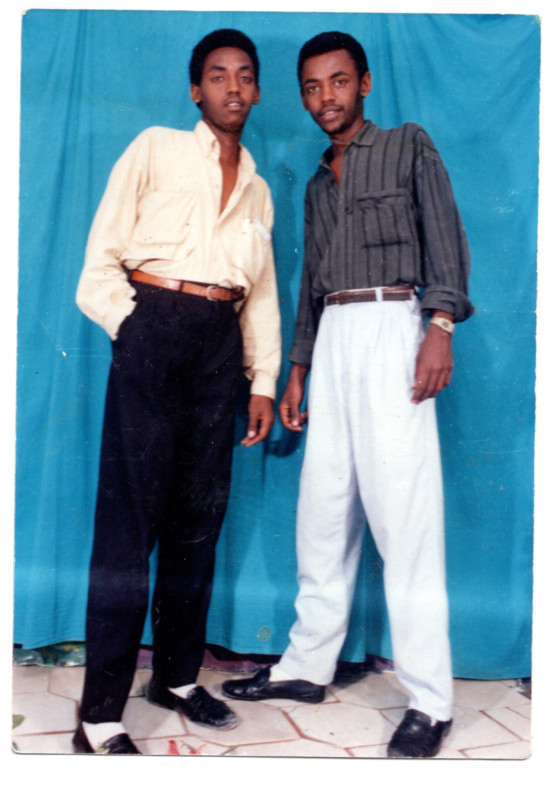

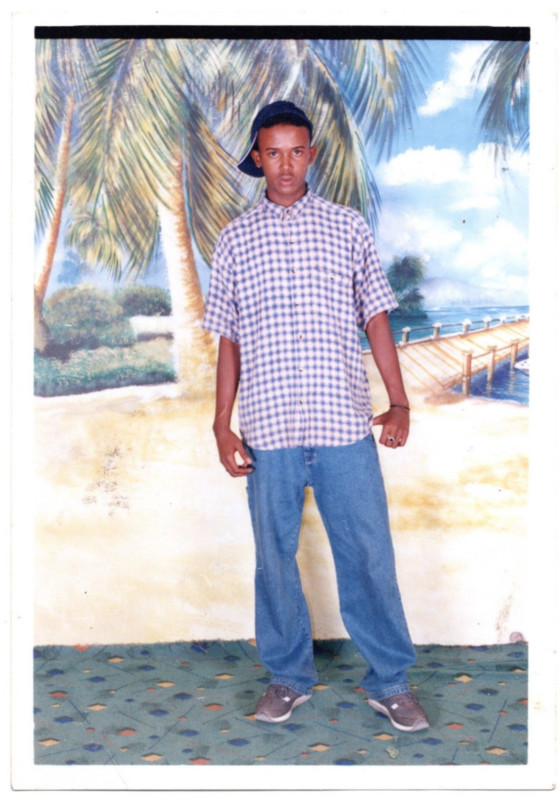

I struggled to find meaning and connection with that photo and was instead drawn to captured moments of Somalia after independence from Britain and Italy in 1960, and my own family’s personal archive from that period. The portrait pictures that I had come across which were taken in photographic studios that were established across Somalia, where the sitter was required to present themselves in the finest clothes against an elegant backdrop to present the likeness of middle-class wealth, and respectability. There is a sense of playfulness with the exterior scenes and props that are often disjointed from the present reality of the sitter. A potent means of self-definition at a time of considerable change, emblematic of a new metropolitan Somalia. The images are striking, particularly to new audiences, as they are not part of a previously available visual catalogue of colonised Somalia, a Somalia that most white institutions have presented.

I had only these images. Never having the opportunity to visit where my parents came from, I clung onto these second-hand memories. I asked myself, what did they bring with them when they fled as refugees? Did that memory of a peaceful Somalia impact the lives they led, and the trauma they carried?

I was also interested in stories of diaspora in those cases where a national archive does not exist, where memories, both material and intangible, are no longer connected to the space where they were formed: where we have to rely on personal archives and those held in institutions outside of Somalia. This questioning led to a project that I developed, called Healing Through The Archives in partnership with Autograph and Numbi Arts. I invited the community to bring in their photographs in the hopes of establishing a community archive of digitised studio photographs taken in post-independent Somalia, and before the civil war. Once stored as family photos, a record of one’s past, they take on a greater meaning. When these places and moments can no longer be replicated by your generation or the next, how do we connect to those captured moments of joy, and being carefree? What do they mean to us then, and now? How does this become a collective experience, a collective loss, a collective mourning?

The archive can be reconfigured as a space that is not just about preservation and limited access to the past but plays an active role in the present, enabling healing. Kurdistan was a long-term project by Susan Meiselas which aimed to create an archive of the Kurdish people’s struggle for nationhood. In the 2015 book Dissonant Archives, Ariella Azoulay chapter reflects that through this project, Meiselas “insisted on restoring that which had been nearly displaced inside the imperial narrative and later the national one while turning the archive into a platform of rehabilitation of a community.’

What happens when these archives held in institutions are digitised and displayed online—where these images are extricated out of archival structures; where the process of classifying and naming are inherited from a system whose taxonomy reflects European values, and ideas of who the information is for, and who is able to access it? Moving from analogue items to digital pixels, they are rendered timeless, but the violence of their becoming and ordering is reinscribed within a database.

The works of Melissa Adler and Yirga Gelaw Woldeyes speak about the epistemic violence of what’s collected, catalogued and displayed online, the representations of knowledge that are meant for a universal public but are built upon principles developed in the midst of imperialism in the 19th and 20th century, where ideas of whiteness and race impacted the design of classification and continue to do so today.

So how then do we then fill those gaps and create a counter-history? Is it by commissioning work, or engaging with photographers that have a practice that sees beyond the gaze we are used to? Or can we fill those silences with imagined stories that tell us more than ‘refugee women’ or ‘corpses of children who have died of starvation’? It speaks to the work of Michelle Caswell and Anne J. Gilliand on the emotional impact of these absences and what can possibly be actualized in their place. We consider the role of imagined archives and their potential to capture who you are and what your story is: the work of Saidiya Hartman in Venus in Two Acts explores the limits of the archive, the bureaucratic nature of ledgers, fieldnotes, catalogues, records of function of objects, things. Is it possible to salvage anything from these sparse words? She speaks about the life eradicated by the intellectual disciplines that failed to document the lives of those behind these records. In her paper, Jaimee Swift says, she uses the process of critical fabulation to take factual historical information, imagining what would have happened to these people, what their stories would have been —characterizing them through historical information but also her creative lens.

The archive cannot redeem itself without the voices and the stories of those it captured, without acknowledging what it excludes. It’s not an objective observer of the violence it records. It cannot separate itself from it—the aggressor cannot exonerate itself. The work to uncover our stories, trace lineages is vital in order for us to recognise the limitations of what’s contained in the archive, but also to seek ways where this excavation can be reparative. I am compelled to remember the inimitable Stuart Hall’s words, that this work enables us to ‘re-remember who we are, where we came from and why we came’.

Abira Hussein is a researcher and producer working at the arts organisation All Change, and is a PhD candidate at UCL, specialising in Somali heritage, digital archives, migration, and health. In recent years she has worked with Culture&, King’s Digital Lab, British Museum, and Somali Week Festival.

This project was made possible thanks to support from The National Lottery Heritage Fund.