The Fifth Corner: Expanding the Frame

Fred Ritchin on this era of uncertainty "when the contributions of image makers may have little impact or serve primarily to confuse and further fracture the social fabric" .

Fred Ritchin is Dean Emeritus of the International Center of Photography and is one of the external voices contributing to Beyond Magnum, a forthcoming series of free talks, debates, and discussions themed around the future of photography, issues of representation and self-representation in the genre, and Magnum’s ongoing archive review.

In the following essay, Ritchin discusses why photography as we know it has failed, introducing a series of New Strategies towards creating advocatory photography, in the context of his new educational platform, The Fifth Corner.

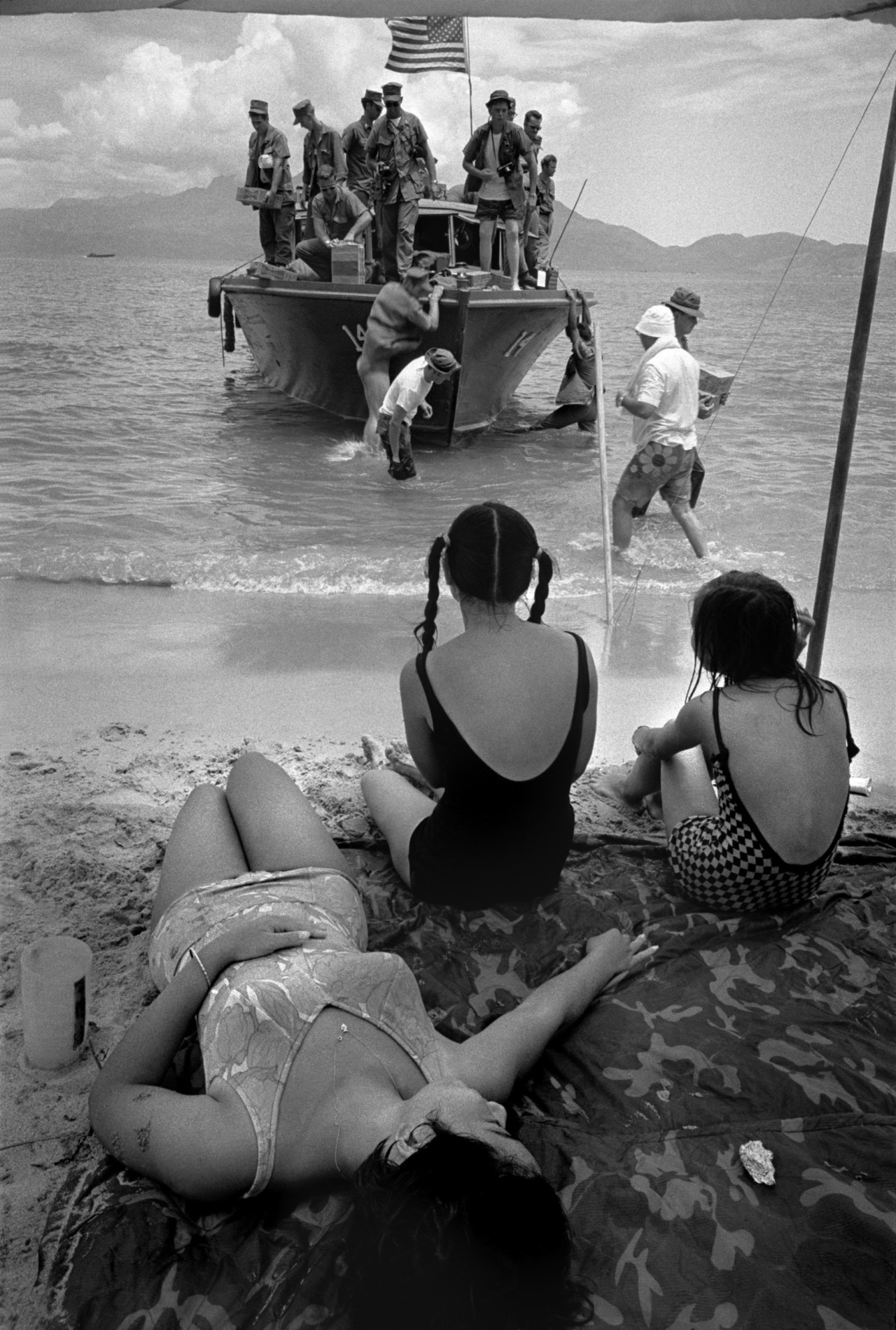

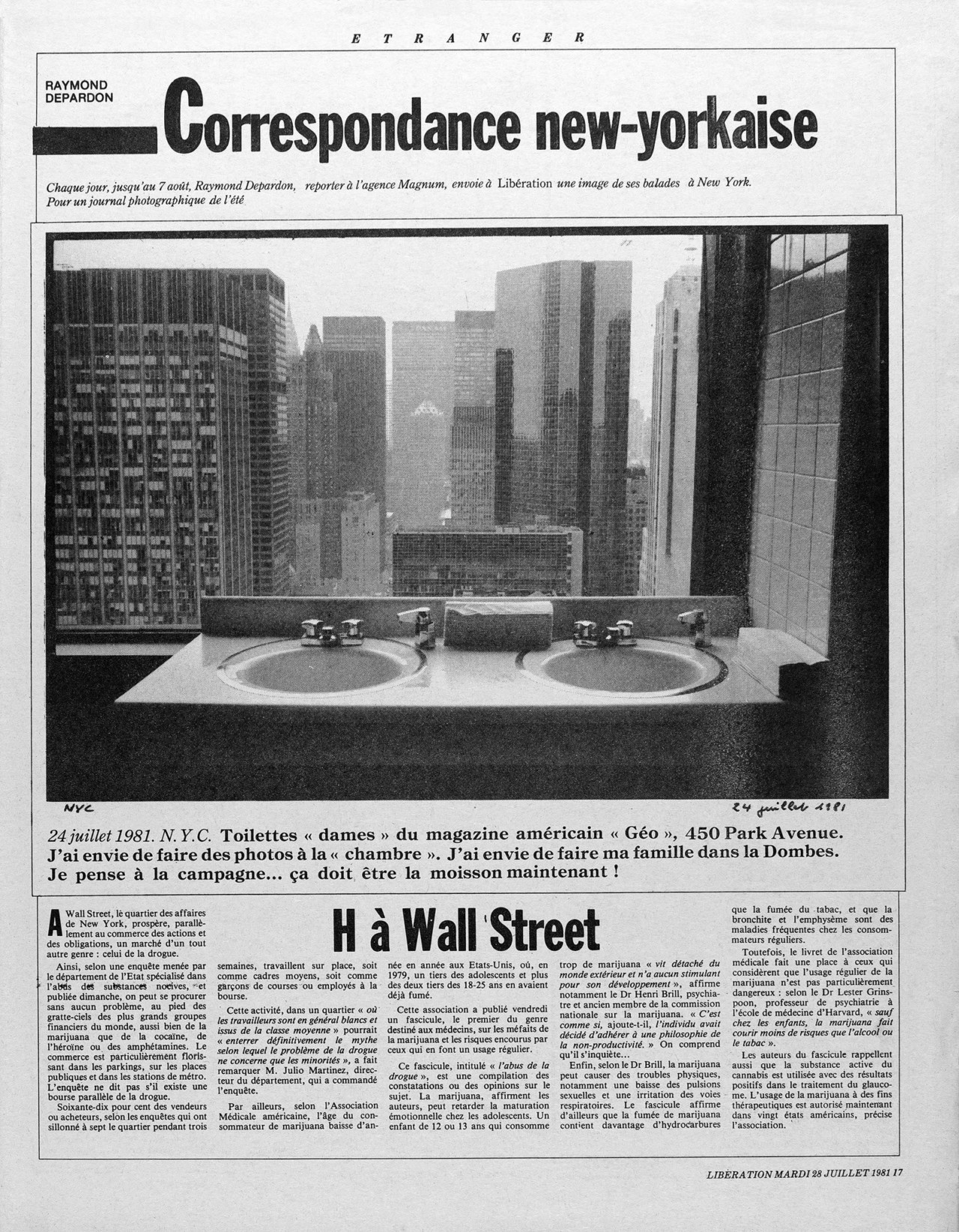

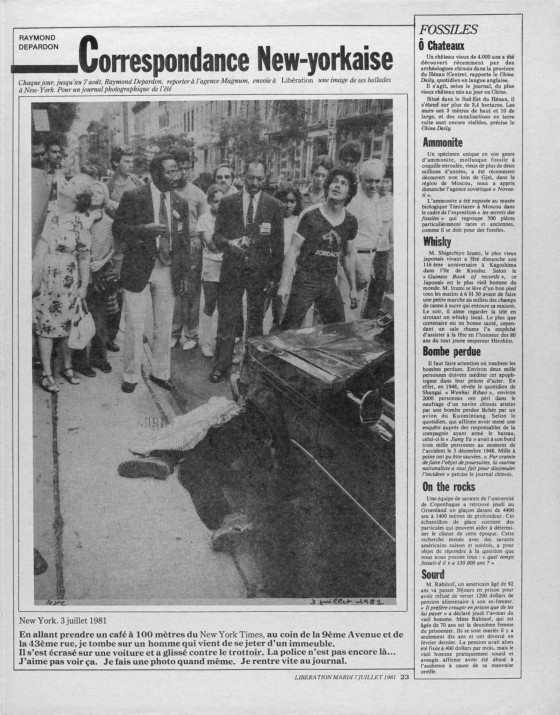

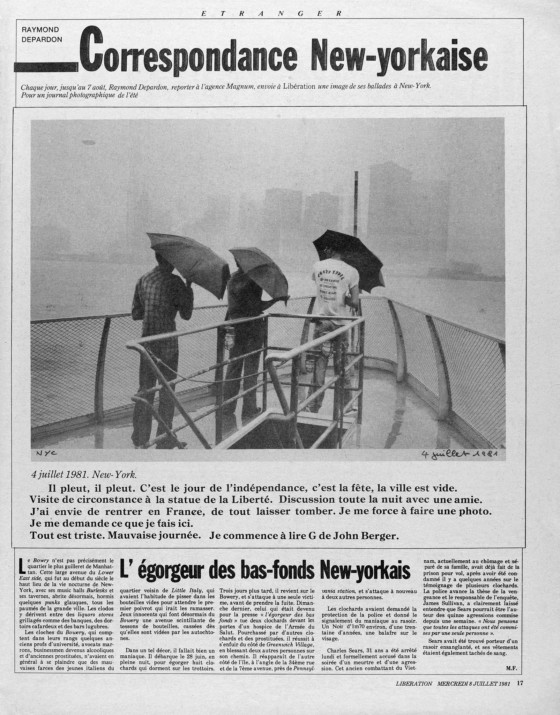

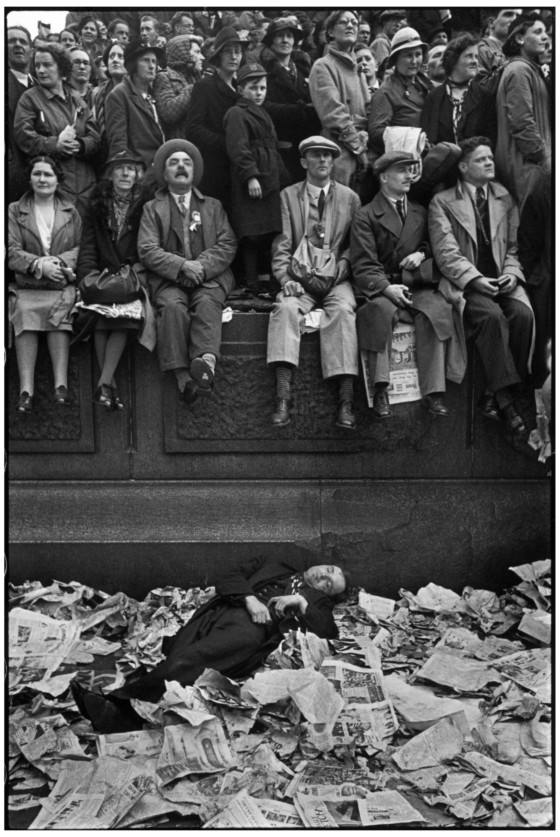

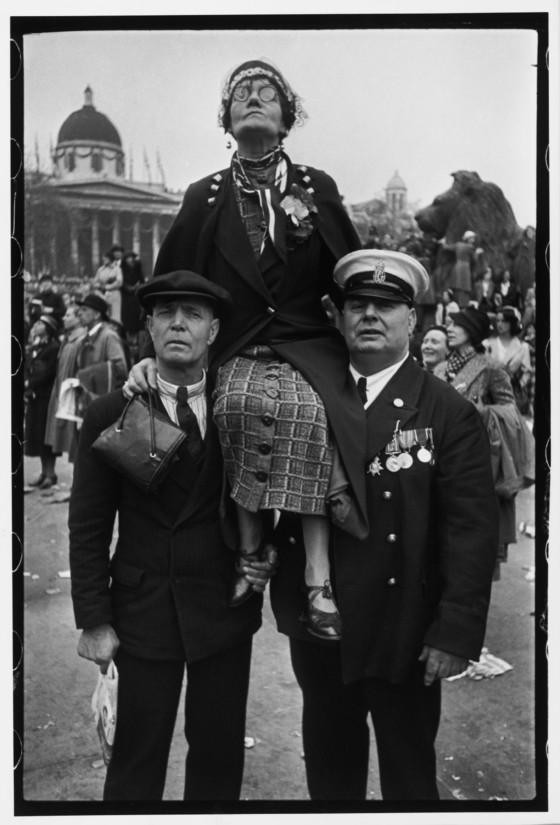

The following text is illustrated by the photographs of three Magnum photographers whose work is explored on The Fifth Corner, or that the project references in its framework. We make use of images from Henri Cartier-Bresson‘s Paris work, discussed in the essay The Ripple Effect, and from Philip Jones Griffiths‘ book Vietnam Inc. which is dealt with in Ritchin discusses Vietnam Inc. We also share cuttings from Raymond Depardon‘s Correspondence New-yorkaise, published in the French newspaper Libération in 1981.

Given the spiraling chaos and pain of the last year, can photographers help societies to heal? Are there proactive image-based strategies that can be useful in reckoning with the pandemic, social inequalities, climate change, and other issues before things deteriorate further? How can people from different cultures and social classes be depicted in more respectful and collaborative ways? Might image makers attain more authenticity and credibility in an era of growing skepticism about the role of media?

The Fifth Corner, launched in the final days of 2020, was created to help spark discussions about these and a variety of other challenges. It is a website constructed to provoke new thinking and underline projects that suggest the transformative potentials of an evolved photography for the 21st century. Rather than looking through the rearview mirror while speeding along at 90 miles per hour, as Marshall McLuhan famously described our relationship to new technologies, The Fifth Corner asks that we press on the brakes and try to find new and useful ways that imagery can help bring us to where, as a society, we actually want to go.

Soon after photography was invented in 1839 the painter Paul Delaroche exclaimed, “From today, painting is dead.” But the opposite was true, as painting vastly expanded its range in a variety of movements such as Impressionism, Cubism, Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism, along with other innovative ways to represent worlds both interior and exterior. The invention of digital media offers photographers similar possibilities of revitalizing their own medium and making it more impactful, including in the service of more just societies.

A paradigm shift occurs in which the older model of photography, trusted as a largely credible record of the visible, evolves into a more fluid, open-ended medium that is considerably more sinuous in the ways in which images can be produced and distributed. Just as many of the first photographs were made to resemble paintings (Pictorialism) and the early cinema could be resemble theater (the films of D.W. Griffiths, for example), the term “digital photography” indicates the ongoing attachment of the current medium to its antecedents without acknowledging the profound and underlying changes that are currently in motion.

Many of the obstacles to photography’s eventual transformation are not technological but conceptual. Why, for example, do we have hundreds of books of war photography and so few of peace photography (published in 1924, War against War! is still the significant exception)? Why is photography still thought of as an essentially reactive medium, “f-8 and be there,” rather than one that can help minimize or even avoid tragedies before they occur? Rather than “taking” photographs, can photographers be thought of as “authors,” providing the context that helps to situate the meanings of a photograph in ways that are more consonant with their intentions?

Might photographic portraits be made in a more active collaboration that allows a subject to assert more of her or his own senses of self, perhaps by encouraging them to critique the portrait and making their critique available to the reader? Along with relying on a more diverse group of photographers, this may be one way to diminish stereotypes and also combat what is characterized as the white male gaze. Can non-linear, open-ended narratives, or hypertexts, accentuate the engagement of readers who then become more involved or “active” (Roland Barthes’s term) in unravelling the narrative and determining meaning? And, as a means of bolstering credibility and transparency, might photographers each supply their own code of ethics, concisely written, accessible to the reader by clicking on their credit or by linking to their homepage?

In a larger conceptual universe, digital media assert the importance of the coded aspect of the image, resulting in the emergence of algorithms that parallel life forms and simulate photographs of people and places that never existed (thispersondoesnotexist.com, for example). It was no accident that coded digital media were invented in the same era as human beings themselves were reconceived as derived from code, or DNA. Digital media become a laboratory for humans to play with various transformative potentials at the level of genotype rather than the phenotypes or appearances that preoccupied photographers previously.

And whereas our previous notion of photography comes out of a Newtonian universe of cause and effect (we are certain that the man jumping over the puddle in the famous Cartier-Bresson 1932 photograph, “Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare,” will inevitably land), digital media are much more about a quantum-like sense of potential outcomes. They resemble more of a hypertext like the Web itself in which multiple pathways, as in Jorge Luis Borges’s 1941 short story, “The Garden of Forking Paths,” provide different outcomes. In many ways it is the photographs, discrete rectangles fragmenting space and time, that are the precursors to this worldview.

The Fifth Corner exists in acknowledgement of this emergent conceptual universe while attempting to galvanize a rethinking of the role of image. Personally, I have been writing and teaching this transformation for several decades, beginning with a piece I wrote in 1984 for the New York Times Magazine, half-a-decade before Photoshop appeared, on the newly malleable digital photograph and the resulting potential for its loss of credibility, a challenge which the photographic industry largely ignored. This was followed by three books on the future of imaging: In Our Own Image: The Coming Revolution in Photography (1990), After Photography (2008), and Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen (2013). These books were meant to underline potential pitfalls that could undermine the credibility of the photograph while encouraging experimentation with the emerging potentials of digital media, with a particular emphasis on strategies that could be useful to forming a more just society.

While I have been picture editor of the New York Times Magazine and served in editorial capacities for other publications as well as in many other roles, I have found the classroom and lecture halls to be the most open spaces in which to discuss these ideas. I once mentioned to the dean at New York University, where I taught for almost a quarter of a century, that given the rapid transformation of media in the digital age, particularly that of photography, I felt the need to teach for the future so that when students graduated several years later they would enter a world that would be familiar to them and to which they could contribute. I likened my approach as a teacher to a soccer player who would kick the ball in anticipation of where a teammate would be after running down the field, rather than to where the teammate was located when the ball was first kicked. The dean responded that the analogy was insufficient, and that it would be better to reinvent the game. In fact, this reinvention is what The Fifth Corner is about.

The site, which will be frequently updated, contains many of my own writings and talks on the potentials of photographic imagery going back to the 1980s, as well as links to innovative projects done by a wide variety of people from both within and outside the photographic community. It also features ideas for New Strategies of image-making such as the Interactive Portrait, Peace Photography, and the Four Corners Project, while under Teaching & Learning there is a glossary of terms, recommended readings and links to resources. There is also an evolving homepage that highlights innovative projects as well as links to a variety of readings, exhibitions, and other media.

So, for example, the section on New Strategies references approaches that could be useful today, some of them having been tried in the past. The “Ripple Effect” emanates from a lesson that I learned from Henri Cartier-Bresson’s suggestion that I read Zen in the Art of Archery, about how to connect with a target without purposefully aiming at it, an approach that resonated with his style as a photographer. His photographs of the coronation of King George VI in London, rather than being made from inside the building where he would have had exclusive access to the crowning of the king, or the target, were made outside in the street of those considerably less powerful who were not invited. These images, depicting the more telling ripples of the event rather than the its conventional center, managed to have found the essential target, or created their own.

The section on Transmedia discusses an unsettling and potentially productive aspect of digital media that allows the underlying code from one medium to be output as another. I did a small experiment taking Alfred Stieglitz’s famed “Equivalents,” his photographs of clouds in the sky that he asserted were meant to represent his own emotional state, and outputting one photograph from his series “Songs of the Sky” as actual sound (music?) by running its digital code through a special software. I also reference the work of the cyborg artist Neil Harbisson, who compensates for his color blindness by using a device attached to his head to translate specific colors into sounds that he can recognize, finding the sound that emanates from walking down a supermarket aisle featuring cleaning products to be particularly stimulating.

Another approach in New Strategies, Peace Photography, features the work of Gideon Mendel, whose photographs, made over four years, of people in South Africa who were HIV-positive and took a regimen of anti-retroviral medicines to stay healthy led to funding from previously reluctant outside benefactors who previously had been skeptical that Africans would be disciplined enough to take their medications as prescribed. Rather than the photographs of the heart-wrenching sick and emaciated that readers had become accustomed to seeing, Mendel’s proactive work counteracted these racist preconceptions and was pivotal, according to UNAIDS, for securing funding so that 8 million others could also be treated.

Another strategy, Avoiding the Quantum Collapse, argues that a caption often unfairly collapses the multiple meanings of a photograph in a way that resembles the impact of the observer on the wave-particle duality in quantum physics. Agnes Varda’s short documentary film, “Ulysse,” in which she establishes myriad meanings for a single photograph of hers that she had made thirty years before, is suggested as a productive demonstration of how one can consider a photograph more broadly, according to its subjects, the photographer, historical contexts, and through other perspectives.

One project currently linked to from the homepage is “nos están marcando” (they are marking us), by Cristóbal Olivares, a former student in the Magnum Foundation’s Photography and Social Justice Program that I co-founded with Susan Meiselas, who used a classroom assignment in interactive portraiture to ask people whose eyesight was severely damaged by Chilean security forces to respond to portraits of them that he made. Another project linked to from the homepage is “Finding Meaning in Pandemic” by Yonas Tadesse, a young Ethiopian photographer who focused on the heroism of health workers in his native country, introduced by the Ethiopian writer Maaza Mengiste. Tadesse uses the Four Corners Project, a template that I conceived allowing a photographer to place various kinds of contextualizing information in each of the photograph’s four corners for the reader to reveal, providing more background information as well as his own code of ethics.

There are many other resources, including a video of an all-day symposium, Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965-75, now on the homepage in which I speak about Vietnam Inc., a pioneering effort by Philip Jones Griffiths to reconfigure the mythologies of war as resembling an attempt at a corporate takeover, exploring the systems and contradictions that underlay that effort. Another video in the Writing & Talks section is from the “Today Show” in 1990, when Adobe shows off its newly developed software, Photoshop, and I unsuccessfully tried to caution that its widespread introduction would severely compromise the witnessing function of the photograph. And there is also both an essay and videos of lectures in which I articulate the Paradigm Shift that has occurred in photography so that, for example, photo-realistic images of non-existent humans are being used to memorialize those who have died in the pandemic, as well as other synthetic images featuring custom facial features and expressions that organizations might decide to employ when trying to appear more diverse than what they actually are.

The Media Resources section features links to several ethical codes from journalistic and humanitarian organizations that might serve as references. The list of UNICEF’s principles, for example, includes the proviso, “Do not publish a story or an image which might put the child, siblings or peers at risk even when identities are changed, obscured or not used,” the US-based National Press Photographers Association’s admonishes photographers to “Resist being manipulated by staged photo opportunities,” and the International Federation of Journalists stipulates that “Journalists shall ensure that the dissemination of information or opinion does not contribute to hatred or prejudice….” There is also a link to the Authority Collective, whose “mission is to empower marginalized artists with resources and community, and to take action against systemic and individual abuses in the world of lens-based editorial, documentary and commercial visual work.”

We are now in is a fraught moment when the contributions of image makers can be critical in helping societies to heal and to advance in more equitable ways. It is also a moment of enormous uncertainty when the contributions of image makers may have little impact or serve primarily to confuse and further fracture the social fabric.

The Fifth Corner is meant to help provoke a discussion and provide examples so that each of us, and the communities to which we belong, can consider how best to move forward. The stakes are considerable.