From the Arab Spring to Tunisia’s Neglected Mining Towns

2019 Magnum nominee, Zied Ben Romdhane, discusses the Tunisian revolution's effect on his photography, his work on the nation's neglected industrial workers, and the benefits of taking one's time

Tunisian photographer Zied Ben Romdhane became a Magnum nominee at the collective’s 2019 AGM. His best known work, the 2018 book West of Life, deals with neglected populations in Tunisia’s south, and specifically with the nation’s isolated – yet economically crucial – mining communities in and around the region of Gafsa. While Ben Romdhane started his career as a commercial photographer, the changes he witnessed in both Tunisia and in the media at large during the Arab Spring saw him increase his focus on making documentary work. Here the photographer discusses the advantages of a slow approach to documenting both communities and individuals, creating visual unity in diverse work, and redressing the imbalance of media coverage in his homeland.

A curation of Ben Romdhane’s work is now available as fine prints, via the Magnum shop. You can see the selection here.

You started working in commercial photography – so how did you come to be involved in the sorts of documentary projects which led to your recently gaining nominee status with Magnum?

I was indeed working as a commercial photographer at first, but I have always pursued my own documentary projects, in my own time and I have always loved documentary. Generally speaking all the documentary work I have made has been self-motivated, rather than through editorial assignments, for example. So, as a result all my documentary work also been personal work. Generally, I do commercial and advertising photography to support that. These two ways of working are, for me, totally separate.

You have spoken elsewhere about the effect the Arab Spring had on your work. How did the revolution in Tunisia impact your approach to photography?

I think the change in my photography – which happened around the time of the revolution was down to two factors… One being, quite simply, the age I was at the time and the other being seeing the role and impact of documentary work and information-sharing in general, at first hand.

Another key effect on my work was that before the revolution, though I had tried to make documentary projects, it had always been difficult. Prior to the revolution covering the real issues in the country was not easily done… After the revolution one found oneself with a relatively good level of freedom of expression, and I could at last really try to cover serious issues in Tunisia.

Finally, the new democracy led to a transition period which saw a lot of public discussions, internal fighting, and politicking – this period in a wider sense motivated me to experiment more with my work, and how to best express my thoughts.

Almost all of your documentary work has focused on Tunisia – is this a wilful refusal to follow ‘big’ stories abroad?

I try not to be drawn away too much. There are of course these stories on the international level or on the global scale which might be big news and are attractive for those reasons, but while I might go abroad to work for short periods, I find that when I do so it’s hard to be fully engaged with the issues at hand. In contrast, when I work in Tunisia, when I have the ability to take my time, I can fully understand the issues and I can understand what’s really happening.

Generally speaking, a personal project I want to pursue will take me years. Everywhere there are stories, and of course every country has its issues – that goes for modern and less modern nations alike. Often of course issues in any one place hold a relevance to wider, international, or global issues. The key factor to me is spending enough time on any one issue to bring something deeper to the work.

So, in answer to your question: I talk about issues in Tunisia a lot because firstly there are a lot of them, and secondly because I have access to them and as a result I have the chance to work on them in depth over time.

"While the region is massively important to the nation, the villages there are totally underdeveloped, neglected in contrast to the wealthier coastal towns and cities"

- Zied Ben Romdhane

Your best known project, the book West of Life, seems to me to be a strong case study for just what you describe here: a local story, to which you had comparative ease of access and to which you applied yourself over a long time. And, as you said, it’s a story which reflects wider issues that can be seen in a non-local context. Can you tell us about the work?

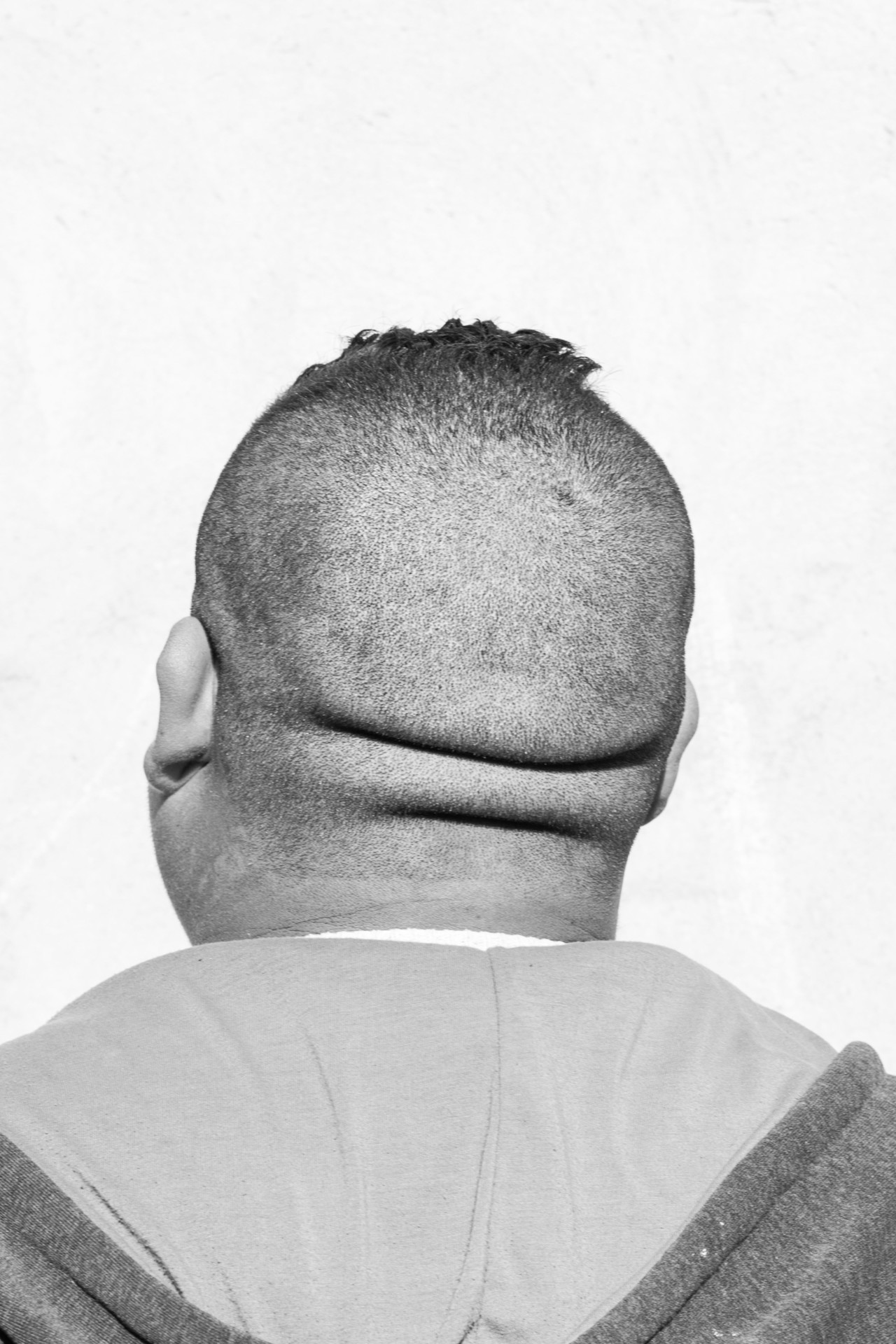

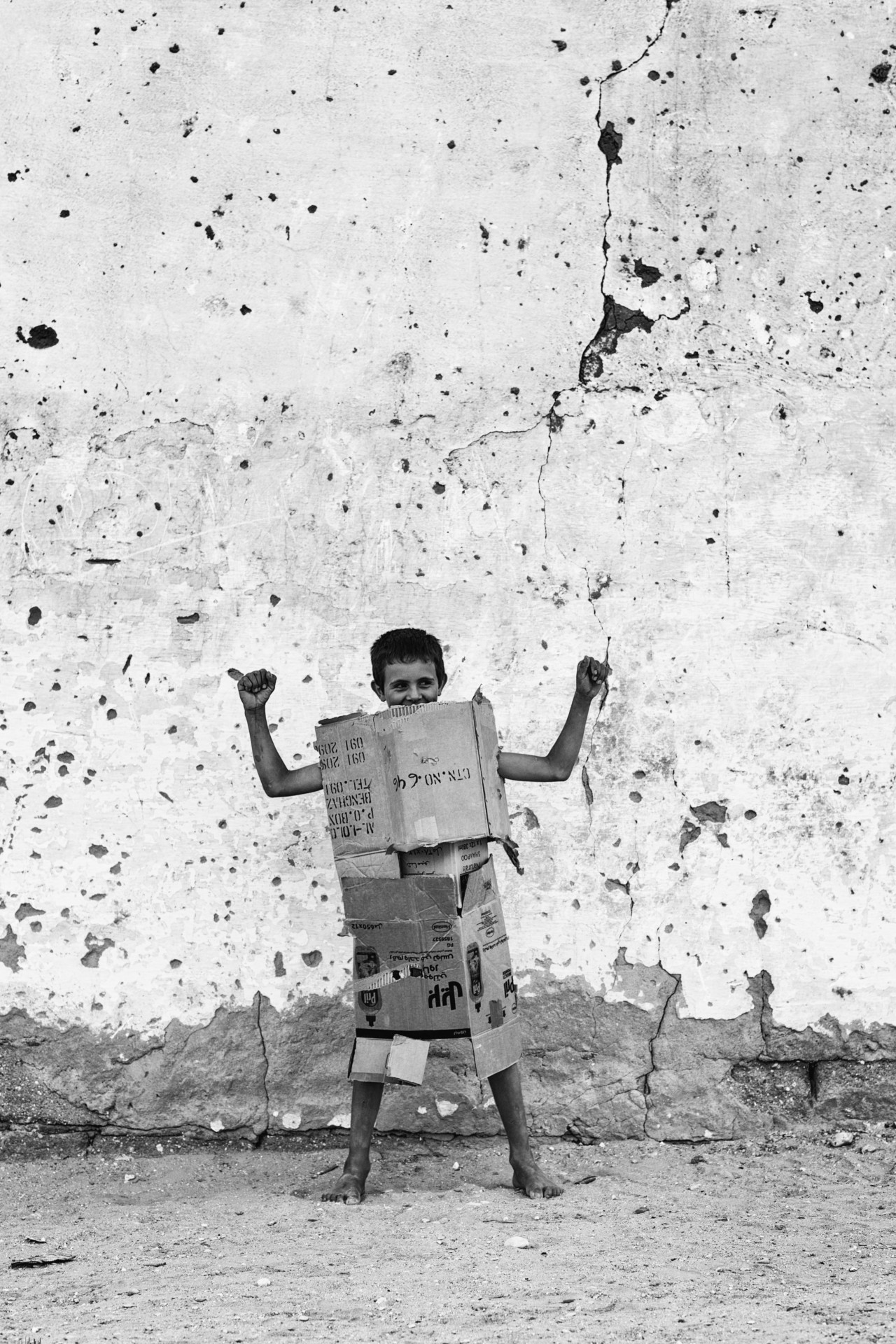

West of Life is about a mining region called Gafsa which is key to the phosphate mining industry in Tunisia – one of the country’s core industries. Following the revolution there was a lot of discussion about the region, and the hardship there. It became the focus of a new social movement. While the region is massively important to the nation, the villages there are totally underdeveloped, neglected in contrast to the wealthier coastal towns and cities. These issues became a core focus for the new post-revolution government.

I travelled to Gafsa around that time and – unsurprisingly – the issues at play run far deeper than they had been depicted as doing in the media at large, or by the politicians. What I found was the extent of the history of the issues. These phosphates were first discovered in the late 1880s, and large-scale extraction of phosphates started when Tunisia was still under French rule, and continues today. The French occupation brought workers into this area from its colonies – from Morocco, Algeria, Libya and from the existing towns around the south of Tunisia.

Villages started to grow up around the mines, inhabited only by mining workers and their families. There’s no agriculture in the region, no commerce so people had only one route for employment. Over time the villages grew into towns, then cities. But still they were totally reliant on the mines. Because these people came from different regions there were internal clashes between ethnic groups, and friction grew.

How key to making that book was the approach you mentioned before – the slowness of working, taking time on a single issue?

I don’t arrive in a place hoping to work on any one idea or with a subjective view. I arrive and at first I only ask questions, trying to come to understand the situation. For some time I went to Gafsa every weekend, by train. At first people were reticent about talking to me, they said lots of media had come there recently and that they had spoken to them, but that nothing had changed.

So, firstly I tried to convince them I wasn’t trying to show any one thing, that I didn’t have an agenda, I was just a photographer wanting to show what was happening. People warmed to me. And after a few months I found myself working closely with people there. This long-term approach is really important to me, it’s key for the subjects to believe in the project, but also for me to get a deep understanding of any given region and the issues.

That approach and those motives were also important to my work made in Tatouine, a city to the south on the way to the border with Libya. It is, like Gafsa, a harsh place to live. I think, again, it was about sharing a view of a place that’s not usually seen – the north of the country, the more affluent coastal area, is well covered on TV and in the national or mainstream media, but the southern regions far less so.

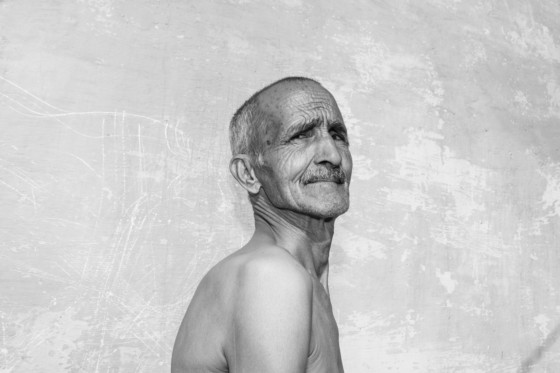

Children of the Moon, your series about people suffering from the genetic disorder Xeroderma Pigmentosum (XP) which leaves them extremely vulnerable to damage from UV light, at first seems totally different from your Gafsa work, but perhaps that same slow, careful approach to subjects proved particularly useful here?

The main trigger for that project was my own curiosity. I have a friend who works as part of an association that takes care of people suffering from XP in Tunisia. A conversation with her left me with many unanswered questions: how do these people hide from the light, do they live in absolute darkness? How do the kids go to school?… Slowly a story took shape in my mind: an idea formed around an imaginary environment that I envisioned for them, that’s what sparked my intention to make this project.

The process of being alone with a child suffering from XP, for several hours a day, for an average of one week each, could be considered somewhat intrusive. I had to ”take some space” in their world. These people have a limited and restricted social life and I had to introduce myself into that limited life. At first the subjects are full of questions and yes, getting them to open up takes time.

For the project I selected the photos that represent what could be considered the brighter side of their situation. I discarded the more “dramatic” images. Some of them were very innocent kids who were not aware of the very real dangers of their situation, it was a must for me to protect their dignity and to present them the way they wanted to be seen.

"A portrait or an abstraction or a landscape can represent only certain aspects of a story. I take a broad approach in order to reflect wide-reaching issues"

- Zied Ben Romdhane

Across these projects the topics and themes change, as do the types of photographic image: reportage imagery, portraiture, abstracted landscapes are all present … Yet your use of black and white seems the only constant?

To me, using black and white keeps things simple! To add to that simplicity I generally only use one of two lenses – it lends the work a sense of continuity which means the images work together better, there’s greater consistency. It’s a way to make a cohesive feeling body of work even if the subjects, issues and places may vary.

I think my attempt to have a broad, general understanding of a given situation or a story leads me to engage with various photographic formats. A portrait or an abstraction or a landscape can represent only certain aspects of a story. I take a broad approach in order to reflect wide-reaching issues.

What do you see as the key unifying thread that runs through your personal work?

I think Tunisia is in a phase of transition. Every country has passed through a similar phase, or will do in the future. I am interested by that phase. In terms of my projects I think I am working on issues that are probably already being discussed – mining, environment, sand encroachment or whatever else. But how we approach and discuss these environmental and social issues is what’s of interest to me. What’s fascinating is how close you can get to these issues in a chosen place, and how much you can open up the discussion around them through your work.

Of course, one of the things about photography that is so interesting is its ability to take you to new places and expose you to new stories: to reveal things you never expected. However, I am Tunisian, and with that comes access to issues in Tunisia and benefits in understanding them. I think for this reason, at least in the short term, I will likely continue to focus on the places I know how best to explore and open these conversations up in.