Omaha, Nebraska: American Masculinity in the Political Maelstrom

Gregory Halpern speaks with Matthew Leifheit about his new book - a reproduction of his scrapbook of contact prints made in the Midwestern city

Omaha, Nebraska is a place I have never been. As an outraged, latently gay teen in rural Wisconsin in the early 2000s, I knew the city mostly through its music label Saddle Creek, which put out records by Bright Eyes and other bands whose indie anthems twanged in harmony with the teenage angst I felt in my heart. “Out west they are moving dirt / to make a Greater Omaha / another franchise sold / so there are even more restaurants per capita,” cried Conor Oberst in a 2002 Desaparecidos song. I too had witnessed the construction of strip malls in corns fields as America engaged in an immoral oil war overseas, and bought a black t-shirt emblazoned with George W. Bush’s face and the slogan “Not My President” to express my rage. Many of my peers, sons of midwestern industrialists and expansionists and corporate farmers, wanted the same things as their increasingly conservative parents, and I wanted no part of it. Likewise, these people regarded me with dire suspicion. Even now, 10 years later writing from my desk in Brooklyn, I feel some degree of guilt in admitting this dynamic—in the middle of the country, there is an unwritten and indirectly spoken rule not to rock the boat, not to want something else or something more, to strive to maintain the status quo.

But it was not only the rapidly shifting political climate of this place that left little space for me, it was also a particular brand of masculinity. Robert Brannon’s four tenets of John Wayneian manliness—no sissy stuff, the sturdy oak, the big wheel, and give ‘em hell—were being enlivened by George W. in press conferences on TV. But they also might as well have been written on the locker room door in my high school. Omaha is a different place than where I came of age, certainly much more urban, but the name conjures in my mind a montage of men holding gas torches welding great machines of destruction, of sparks flying against a cloudless, open sky. I knew the men who lit those torches when they were boys, and my relationship with their memory is as angry as it is tender.

"I was fascinated by Omaha, attracted to and repelled by its brand of masculinity"

- Gregory Halpern

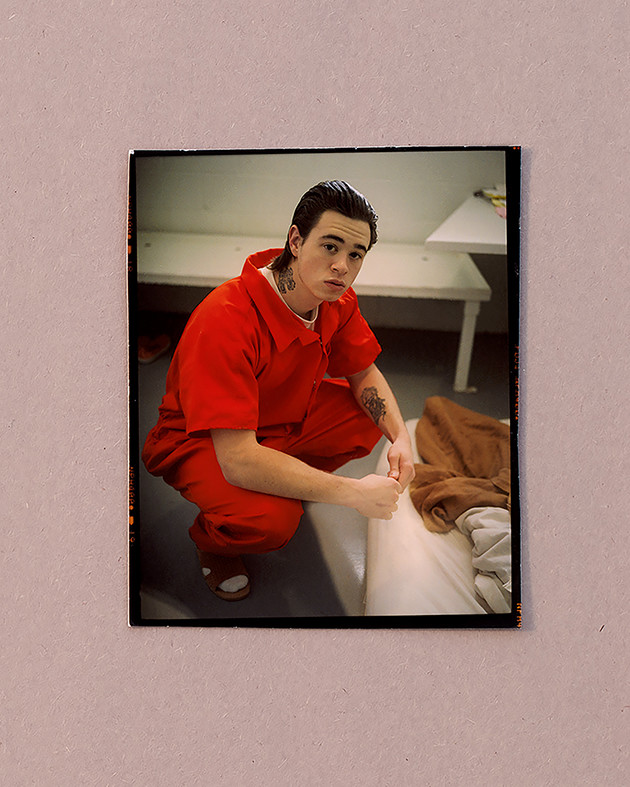

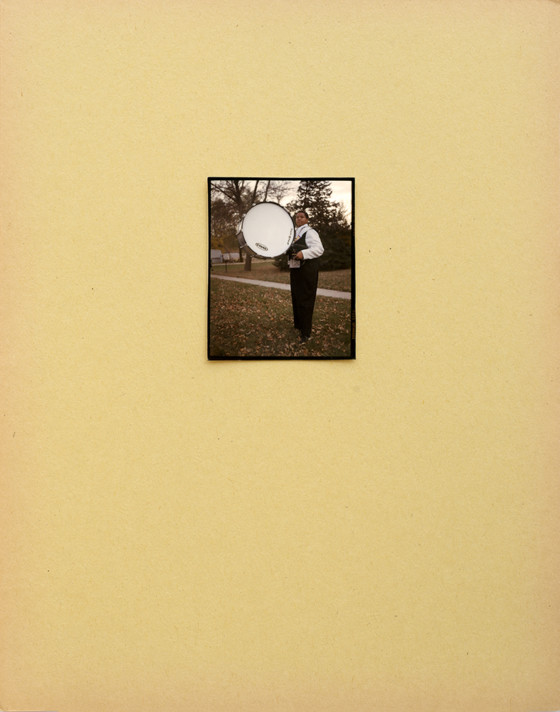

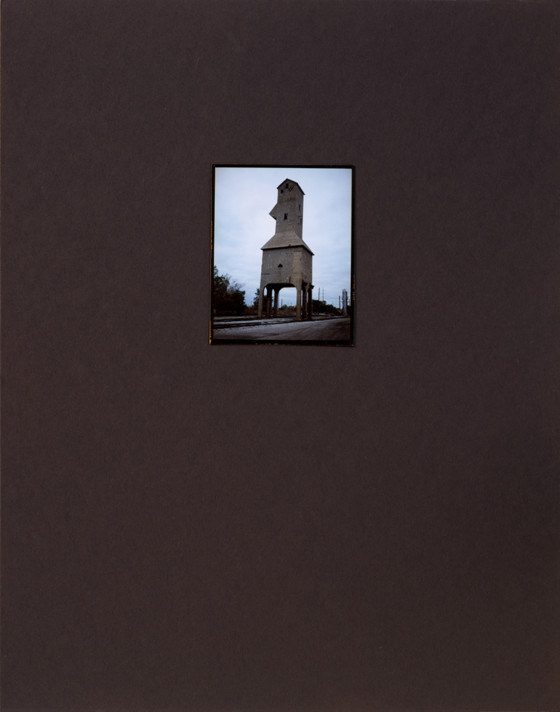

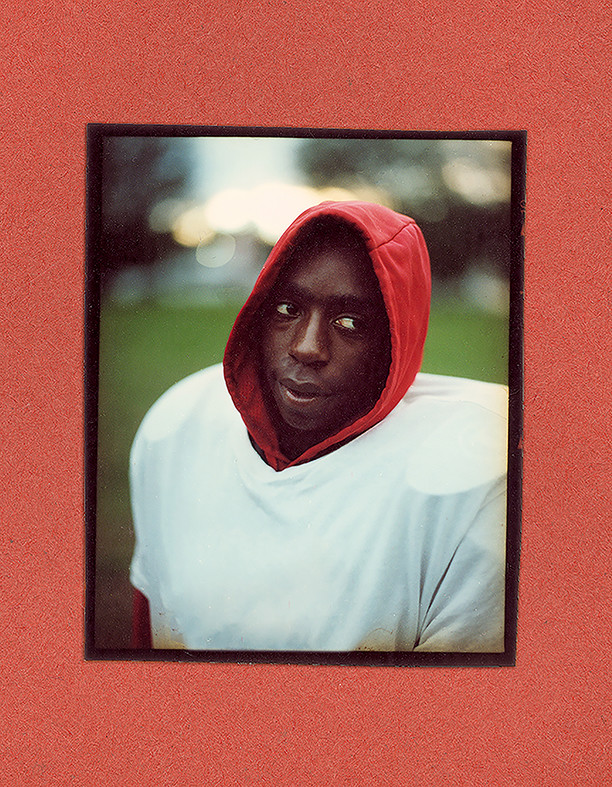

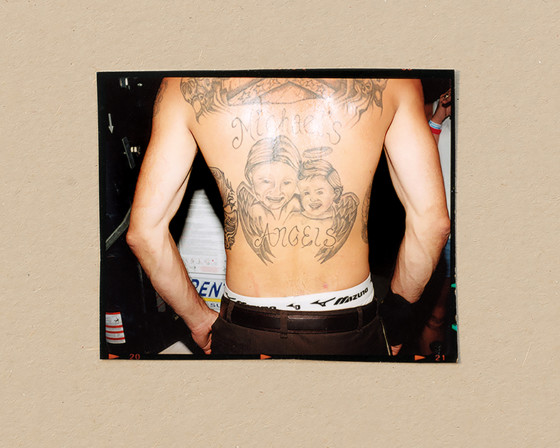

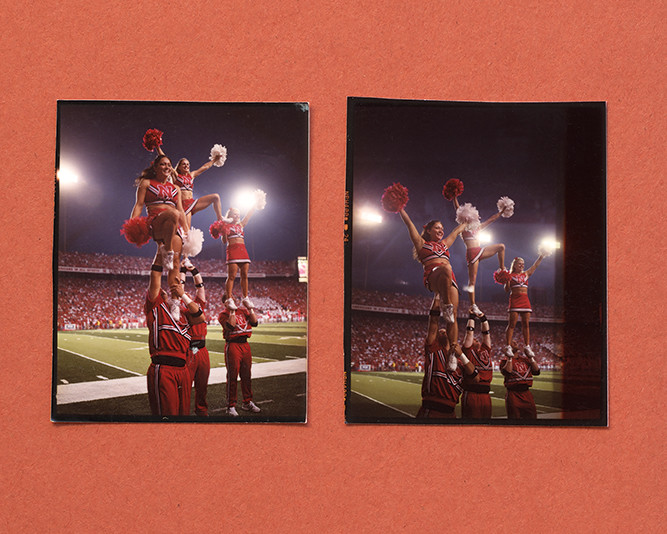

Over the past 15 years, Gregory Halpern has been photographing in Omaha. He, like me, is not from Omaha, though he is from Buffalo, NY, which shares some characteristics with industrial cities of the Midwest. His work in Omaha began during a residency at the Bemis Center in 2005. He had never lived in the middle of the country, instead moving from New York to Massachusetts to San Francisco to Rochester, NY, where he is currently a professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology. But something called to him about Omaha and he went back sporadically over the years. “I was fascinated by Omaha, attracted to and repelled by its brand of masculinity,” he told me. Halpern cut and pasted contact sheets of photos he took in a sketchbook made of fading construction paper found in an abandoned school in Omaha, cataloguing his experience in a poetic syntax of glances that accumulate to form a fractured, aerial view of the place. Across many times and situations, Halpern plays a nearly omniscient witness. But this is a an omniscience of surface, of light and shape, that somehow provokes an emotional response without pretending to know the innermost thoughts of the characters in the play. The scene is set in a period of American decline that subsequent generations will surely be able to identify by sight. First, a junkyard dog at daybreak, then a boy scout troop, a football game, then inmates at a federal men’s penitentiary, then a slaughterhouse. Though technically the work of an outsider, something about this perspective seems right to me. Though I haven’t been to Omaha, I can relate to these images and think they convey one person’s experience of the place, and what he was thinking about when he was there. I don’t know if this is because I grew up in the Midwest and have seen the many examples of the kind of cowboy masculinity Halpern describes in the work. Yet, despite any political commentary, beauty is in no short supply. Beauty tempers even the darkest images here, and to me represents hope. Halpern’s book shows the contrasts of Midwestern America as they are, or at least as they have appeared to me. It is as close to living those contrasts as an outsider might be meant to come, and plays to the particular strengths of being someone not entrenched in any particular local agenda, apart from making pictures.

Halpern’s Omaha Sketchbook published by MACK Books is available now.

Halpern will also be giving a talk on the work, and signing copes of the book, on Tuesday 24 September, at 7.30pm in the Strand Book Store, New York City. More information, here.

As someone not from Omaha, but from the Midwest, I have a lot of complicated feelings about the subject, and am therefore sensitive about how the area is depicted. But something about the book overall rings true to me, in that it seems like somebody’s perspective who comes into a place and just sees voraciously, but makes no claims to really understand it fundamentally. Would you agree with that? The small size of the contacted images also echoes this distance to me, it makes the figures harder to see and gives us less access to peoples’ faces, which often seem to convey so much emotion and understanding in photographs. And for me, there is a way these elements come together to describe your position. At the same time, the particular syntax of the images creates this kind of overarching yet extremely fractured view of the place.

I like when work creates a kind of unexpected cohesion, despite disparate elements. A range of imagery that borders on dissonance excites me, and it’s related to why I would never claim to fundamentally understand Omaha, or almost any person or place I photographed for that matter. But I also don’t think it’s necessary for what I’m trying to do. The work is as much about something internal/personal—as well as something universal and beyond Omaha—as it is about the place where it was made, or the place used as the setting. I think it’s just as productive to not fundamentally understand your subject, or even to assume that should be the goal. I don’t think that’s the artist’s job. Maybe it’s the job of the scientist, the campaigning politician or the activist. I might counter your question by saying that the artist’s responsibility is to never know, to be comfortable in their uncertainty and to allow wonder and humility drive their interactions with the world around them.

Yeah I guess for me there is a visual language common in documentary photography that is meant to convey understanding between the photographer and subject—a certain kind of knowing stare into the lens that photographers use to advertise complicity. I don’t see any of that here. Amanda Maddox, of the J. Paul Getty Museum, noted the way the book touches on the subject of masculinity. Could you explain more about that?

The book depicts men almost exclusively. And they are often doing things traditionally associated with masculinity, or with a certain kind of masculine ideal. There are also of course quieter or more ambiguous moments—a man dancing, a man standing alone in the dark, a man staring out the window. I’d say I’m simultaneously fascinated by and repulsed by certain traditional displays of masculinity. I can just as quickly get sucked into a boxing match on television as I can be maddened by the male privilege assumed by some of my students, or even little boys on the playground. I have two daughters, the youngest of whom was born the night Trump was elected, and it’s been impossible not to see the world through the eyes of a young girl ever since. And to see my own privilege and blindness as well.

Another thing that stands out to me in Maddox’s description is that it says the book takes on the subject of Americanness in the “current political maelstrom.” What are some of the things Omaha can express about America? How is the period of time you photographed important?

Well, this is a generalization, but I’d say traditionally-idealized forms of masculinity are celebrated more clearly in Nebraska than on the coasts. And they are visualized and modeled more unapologetically, than in say, New York or San Francisco. Men are men everywhere though, and boys learn that they will inherit—and that it’s their responsibility to preserve—the patriarchy as soon as they are born. I’m not picking on Omaha. I’m not sure any one place is “worse” than another, and appearances can be deceiving, but visually at least there is the legacy of the pioneer and a celebrated tradition of cowboy masculinity visible in Nebraska, which made it a logical place to do this project.

The period of time is crucial. I moved to Omaha in 2005 early on in the US-Iraq war. In 2003, then President George W. Bush gave Saddam Hussein a 48-hour ultimatum to leave Iraq, or else the US would invade. There was a picture on the cover of The New York Times the next day, a still from W’s speech. What struck me was that the still captured something in W’s face that spoke to his supreme (if wounded) confidence, while also capturing something fearful. It exemplified that connection that’s visible often in men between inadequacy and aggression. And weirdly it was also an encapsulation of how when portraiture (or art in general) accepts contradiction into its form it becomes all the more compelling. All of that is to say that I moved to Omaha with the Iraq war and that portrait on my mind, and with W’s sense of cowboy masculinity darkening my understanding of America. I returned to Omaha sporadically over the years but I didn’t pick the project up and aggressively try to finish it until my daughters were born and Trump was elected. So I suppose working on the sketchbook was a way for me to work through some of this over the course of fifteen years in a relatively private way.

One thing that I am immediately drawn to is the analog materials, and the craft of the way the images are carefully cut out. It allows you to evaluate the photographs differently, as one might evaluate a contact sheet, prizing color and composition and the impact of the image at a distance and its relation to the next over fine detail. But in another way, they are also outdated photographic materials on sheets of old construction paper. Why do you think this kind of approach is the best way to say what you are saying?

I started the project in 2005, when digital photography wasn’t really a decent option, and it’s just how I was working—cutting up my contact sheets and taping them into this “sketchbook” I made from old construction paper. I still work this way, cut my contact sheets and physically shuffle them and rearrange them on a table, on little shelves I have made in my studio, or in this case in a handmade book. Film is only outdated, as I see it, in the sense that the mass market offers a cheaper, more practical alternative. For the average consumer, there’s no doubt that digital is better for everything. For artists, however, digital might be better for certain things and worse for others. Oil-painting isn’t outdated because of Photoshop. I like to shoot into the sun, for example, and as far as I’m concerned nothing renders that more beautifully than film. And I like not seeing the picture right away. It’s complicated and illogical, but isn’t all art-making?