Hannah Price on Identity, Projections and Distortions

The 2020 Magnum nominee’s images shift our collective understanding of racial politics and how people define themselves

Born in Annapolis, Maryland; raised in Fort Collins, Colorado; and now based in Philadelphia, photographer and documentary filmmaker Hannah Price has spent years capturing the nuances of racial identities and societal perceptions. Her work is a critique of the negative and destructive powers of visual representation in determining the realities of black people and other racialized groups. For Price, image-making also offers a strategy of recuperating different ways of relating to other people and the world around us. To date, her projects have included: the internationally-renowned City of Brotherly Love— a visual survey of catcallers she encountered in Philadelphia; Resemblance— a series of portraits of inner-city high schoolers in Rochester New York; Cursed By Night, made in 2012-2013, on the perceived threat of black masculinity; and 2018’s Semaphore, exploring how individuals signal their identities.

Price’s photos evince a rare attention to the subjectivities of those she photographs, even as she probes the validity and significance of the social constructs that operate around them. She has previously exhibited in several cities across the United States, with solo shows at Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design, Philadelphia Photo Arts Center, and the Silver Eye Center for Photography, Pittsburgh, while several of her photographs reside in the permanent collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Now, as a 2020 Magnum nominee, Price discusses the political and aesthetic concerns that inform her work, as well as some of the problems and possibilities to be found in using visual communication as a means of fighting racism.

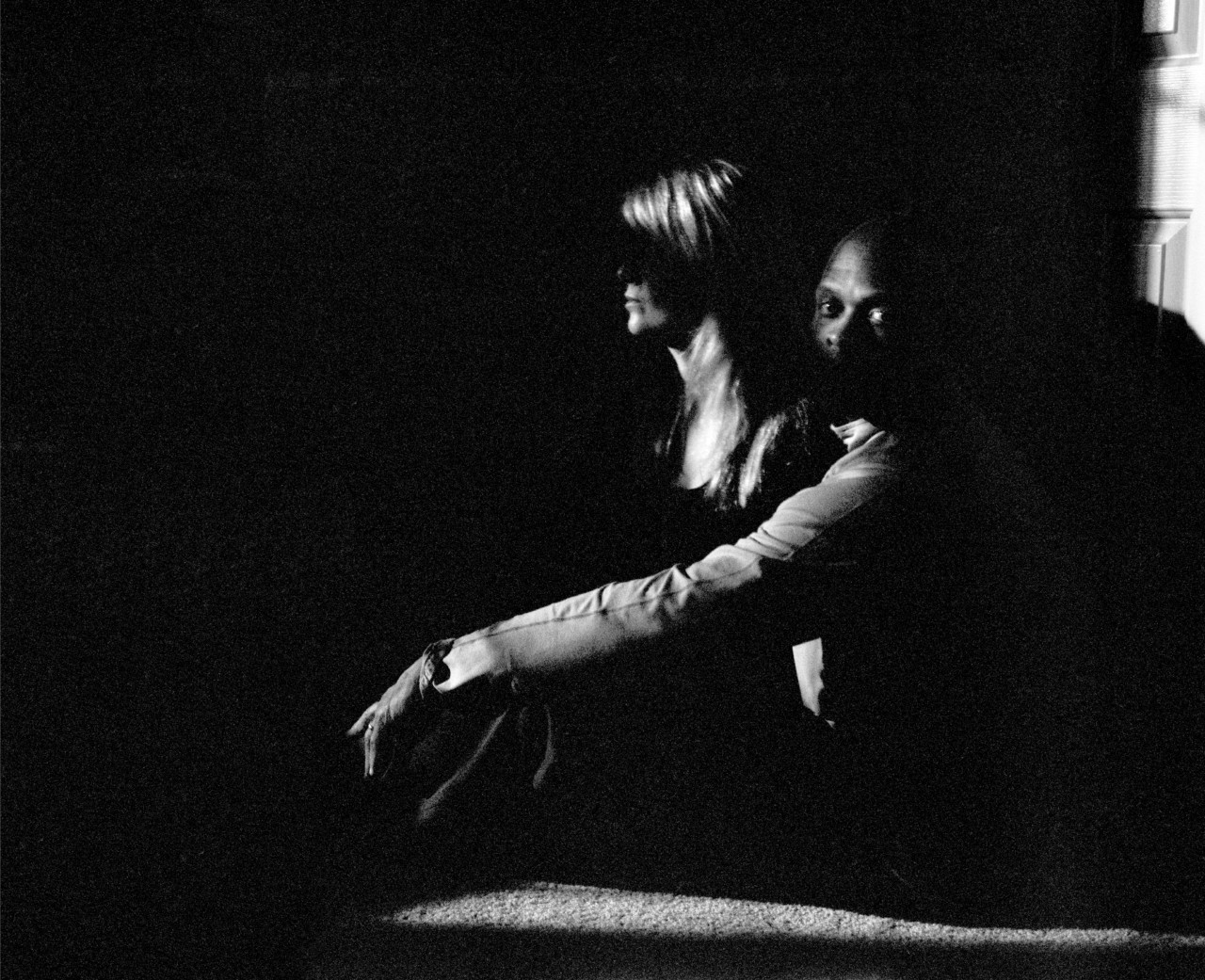

The below image, from Price’s project Cursed By Night, is included in the new Magnum Editions Posters collection, featuring contemporary works from 23 Magnum photographers. These posters are now available, in limited editions of 100 unsigned, and 50 signed priced at $100 and $150 respectively. Each poster is individually numbered with a unique Magnum Editions label that is supplied separately. You can explore the whole collection here.

Can you begin by telling us about your journey into photography?

I became interested at a young age, around 6 or 7. My dad gave me my first camera and I liked wandering around with it on my own. As a child I was very quiet. I always watched people and my surroundings.

That ethic of quiet observation is really clear in your work, especially in photographs that explore questions around identity. In Semaphore, for instance, you focus intently on the inherent fungibility and slipperiness of identity, how our perceptions shape the categories and labels that we assign to those arounds us. Could you talk about how this project came to be?

I like the way you put it. Several years before Semaphore my work talked about race specifically and I wanted to take a break from that. In Semaphore I wanted a diverse group of people, but along the same lines of identity and general projections of society. The concept is that we all have to spell out our identity to people. Just my way of encouraging others to talk to people before believing their perception based off of what a person looks like. The bright white in the images are a reference to the meaning of Semaphore.

Both of your projects, Semaphore, and Cursed by Night, revolve around issues of race, gender and the relationship of the individual to the collective, as well as being connected through a stark black and white aesthetic. Can you say a bit about your use of that medium?

The black and white is on purpose for aesthetic reasons and to speak more politically.

The contrast compliments the polarized political issues of society I want to talk about. I like using black and white to express an “emotional caution” per se, along with the potential death and horror through which we live – due to politics. We can either be divided or accept our true colors and respect another’s being.

Another concern in your work is perception and misperception, particularly the ways in which the perception of racialized people is mediated through society’s distortions and projections. We see this in the description for your project Cursed by Night where you write that ‘black is inseparable from a dense web of figurative connotations almost all of them negative: impurity, sin, death, evil.’ What do you see as the role of the photographer in dealing with and negotiating these projections?

My role as a photographer is to communicate visually. And personally, for Cursed by Night, I want to document life and politics along with adding the concept of horror. Black men being racially profiled has existed forever in America. Using visual techniques to force a conversation on this particular social issue was my personal goal. Mostly, I hope to just make people think about how they themselves react to black men, even though the work is dark and projects innocent black men in a negative light (which is what racial profiling does). This blatant imagery allows me to talk about the concept and how it affects innocent people’s lives –sometimes by taking their lives.I am also proposing that reaching an understanding of the difference between reality, and the perceptions maintained by non-black people, is the only way we the people can help end this curse.

It seems that while others wish to represent blackness as counter to those associations, you take a different approach, one that seeks to show these racist ideas and associations for what they are, as a means of challenging them?

Well, I am challenging the associations in a different way. I myself prefer positive imagery of black men, but I also think it’s important to discuss the reality out in the open – to talk about how negative the projection really is. It’s horrific! I want this image of Cursed by Night to be abstract, I want it to be something of the past. But it’s not, however. The godsend of George Floyd (his name will live on) has made white people realize the horror, and stand up against racism more than before. I’ve always been angered by racism, but today the anger is different. I’m not depressed. This time, I am motivated to challenge the means through which society currently sees black people, as a monolith.

Do you think that photography can contribute meaningfully to that fight, potentially through the creation of alternate forms of representation, or does it simply add to society’s misperceptions and the violence that goes along with that?

I think photography can contribute to society’s misperceptions. It all depends on the mind of the viewer. People do what they want and we can’t control each other’s experiences – people see based on their own experience. Nobody chooses their life, where, or who they come from. Ideally, in my opinion, if society was more integrated, a diverse group of people could have diverse experiences, and there would be fewer social issues. Since I chose to give people photography, I try to challenge people to think about what they see in front of them: if their own projection is true or not, in their situation. And potentially, I help them think about the reality of the images, and the reality of what they see in their own, possible experiences.

Your photographs also seem to be a means of engaging with and reworking your own personal experiences. An example of this is in City of Brotherly Love, where your response to being catcalled was to take portraits of the men who catcalled you. I was struck by how the photos reveal an equal and direct gaze between observer and observed and even a sense of camaraderie and respect. Do you see photography as being able to create a feeling of intimacy and familiarity amidst strangers?

Yeah, definitely. I always try to respect people. I knew I came from a different place [having moved to Philadelphia from the predominantly-white Fort Collins], that I had no expectations, but I tried to feel out every situation. I wouldn’t approach a man if I felt uncomfortable. I was definitely interested in getting to know who they were. Also, they helped me realize I was attractive. Dating was really hard for me, being the only minority in my grade in white suburbia, as a teenager.

Coming from a racially isolated background, your photos appear to consciously encompass a wide variety of people from different backgrounds, races, genders and age groups. This plurality is matched by an interest in the surroundings and environments that these people inhabit. The images comment on how people are shaped by their surroundings and vise versa. Can you say more about the relationship between people and places which your photography examines?

My relationship with the people I photograph is friendly and full of respect. I prefer strangers— people I don’t know— because there is more to discover in the moment. However, sometimes I do photograph people I know for a specific image. I often find the background I want to photograph my subjects in before we meet, or if I photograph a stranger I may search for the right background then and there.

In City of Brotherly Love, it was for personal reasons: I enjoyed photography, and it helped me approach the men and understand this manner — this way of interacting which seems to exist more in large cities. We ended up becoming friendly, and some more than others. However, over the years, that relationship dissipated because I moved for graduate school. Cursed By Night was made during grad school. I went to specific parts of different cities. I met two people, who became friends of mine, and they ended up helping me a lot. They would help me make photographs most weekends; we are still occasionally in touch, but they live in Atlanta now. Semaphore was completely random. Family, friends, old neighbors, and strangers. I try to give images to people and keep in touch, but it’s quite difficult.

Your artistic practice is not consigned to photography. You also experiment with documentary filmmaking. How does your documentary and video work relate to your photography?

My documentary video work relates to my photography by being a part of the same conversation of race politics. However, there I am more of a fly on the wall, instead of adding a more conceptual style to it. With video, I enjoy more “in-the-moment documentary”, as opposed to with my photography, where I invite the viewer to sit with an image. My favorite video on my website is ‘Blueprint’. With my video, I only plan interviews. Otherwise, I find someone to follow. ‘Revisited and Improvised’ is another video work of mine, where I collaborate with the barbershop.

And finally, what’s next for you and your photography?

I’m not sure quite yet, but I know I want to talk about perception again. I definitely want to be a part of the conversation during this time of racial reckoning. Unfortunately, I don’t have anything specific to tell you. I mostly work intuitively.