Henri Cartier-Bresson: Principles of a Practice

The artistic director of the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson on the key characteristics of the Magnum co-founder's pioneering approach to photography

Agnes Sire has been director of the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson for 15 years, having previously worked for Magnum for 20 years. Joining the Foundation in its earliest days, Sire worked on building the archive with esteemed photo editor and publisher Robert Delpire. Sire knows Henri Cartier-Bresson’s practice inside out, and here, she gives a pit-stop tour through the defining characteristics of his approach.

You can also read Magnum Photos’ US Cultural Director Pauline Vermare on Henri Cartier-Bresson’s role in the history of street photography here.

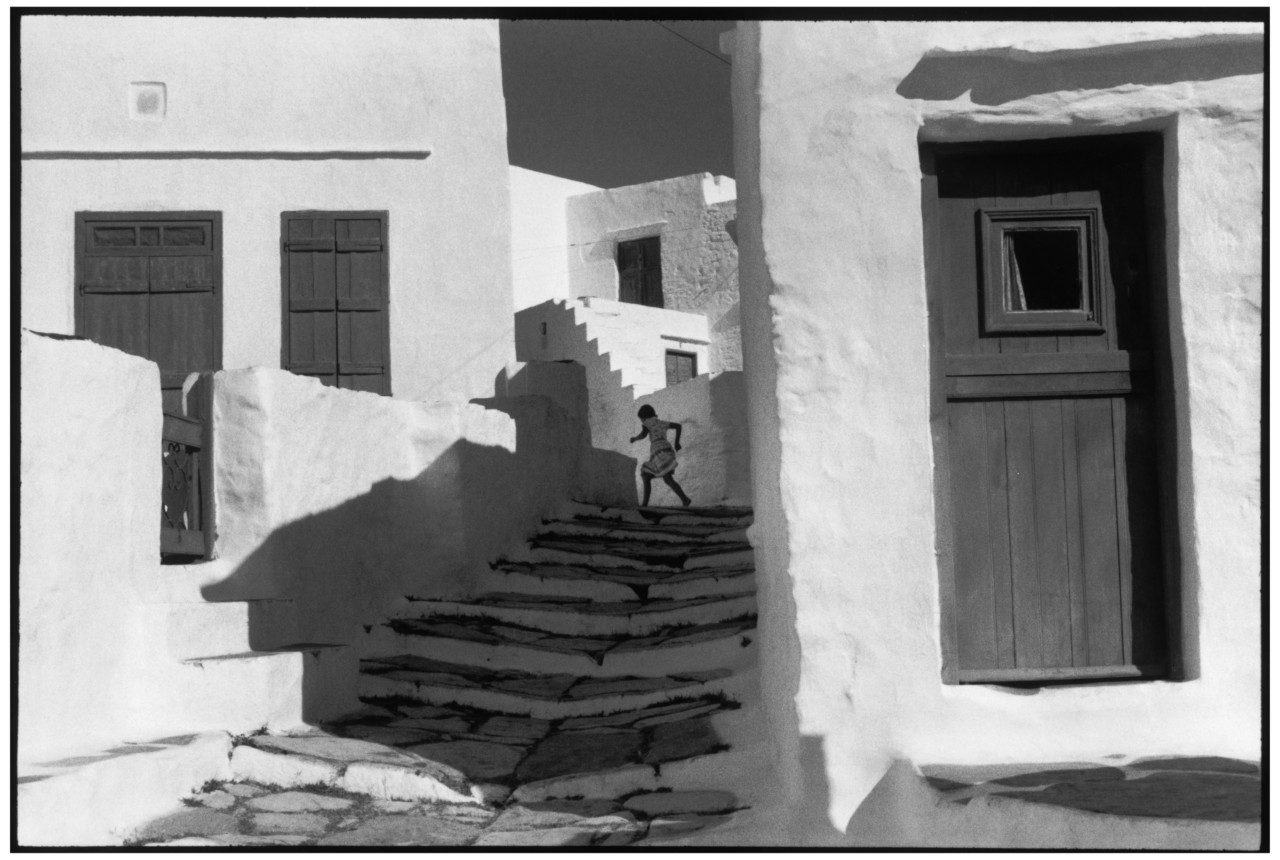

On the Run

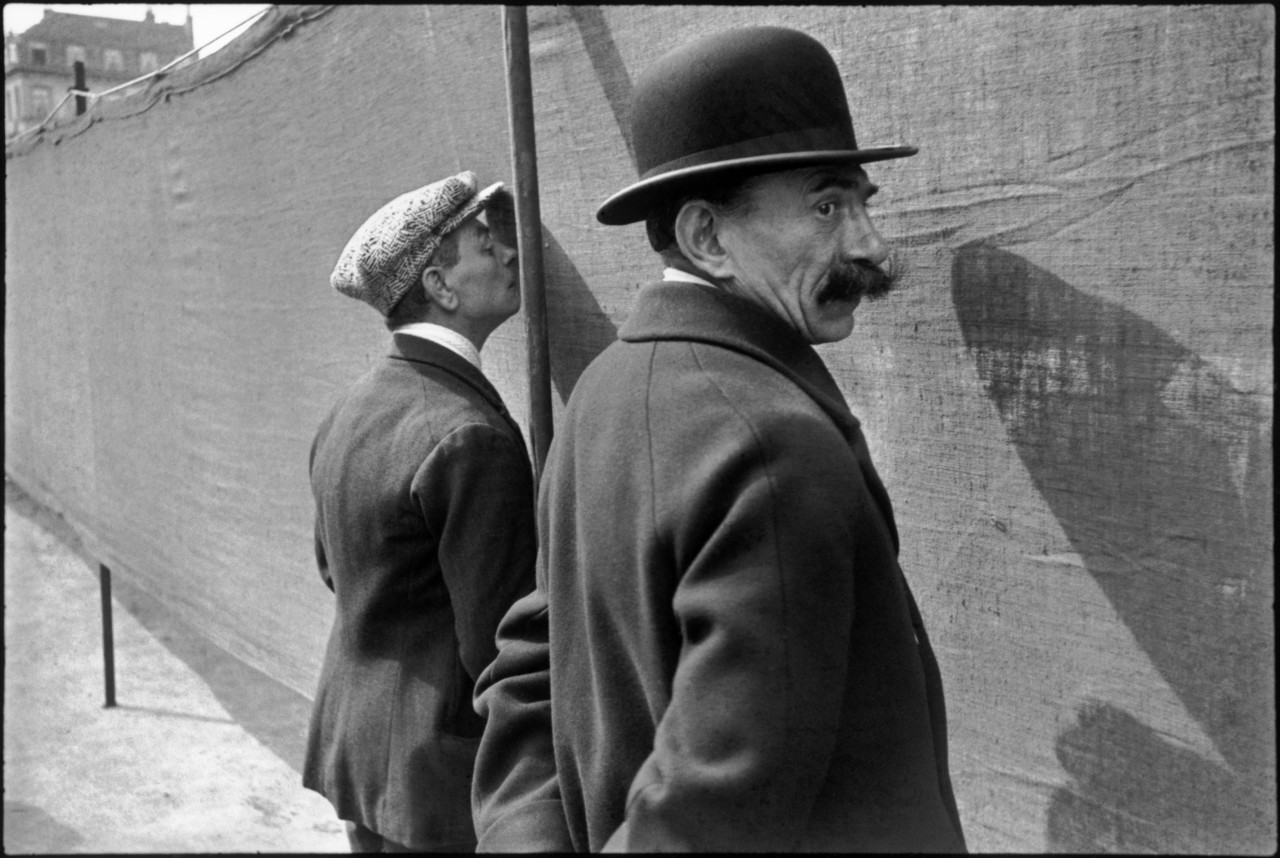

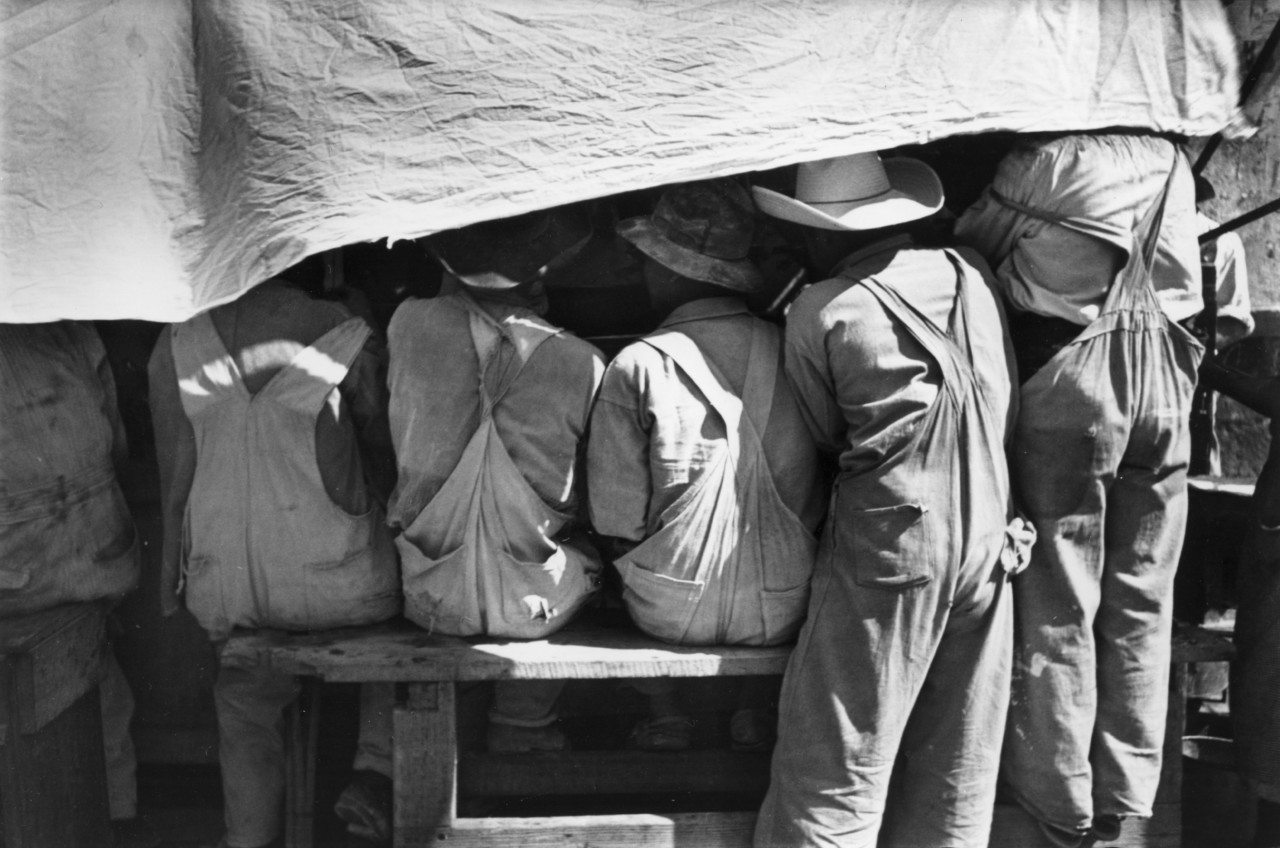

“When he decided to stop at the end of 1960s, Henri Cartier-Bresson would say, “I’ve had enough of the pavement, I want to draw, I want to live in another temporality”, because photography was, according to Cartier-Bresson, ‘à la sauvette’ (on the run)…To him, it was clear that you take a photo in a fraction of a second; he liked to say like a thief, like a street merchant that doesn’t have the right to be there and gets thrown out by the police.

This notion of an image ‘à la sauvette’ was something that Cartier-Bresson especially liked because he really liked the idea of being a little thief – a little photo thief. And there were very often scenes where that was clear, for example, one day he photographed Yves Saint Laurent. He went to his home and Saint Laurent was extremely nervous. Henri Cartier-Bresson was looking at the paintings on the walls at the library and finally Saint Laurent said, ‘Okay, when are you going to take my portrait?’ and Cartier-Bresson said, ‘Oh I took it a long time ago.’ He was not someone who set a whole thing up, who had to take photos with a light and a backdrop.”

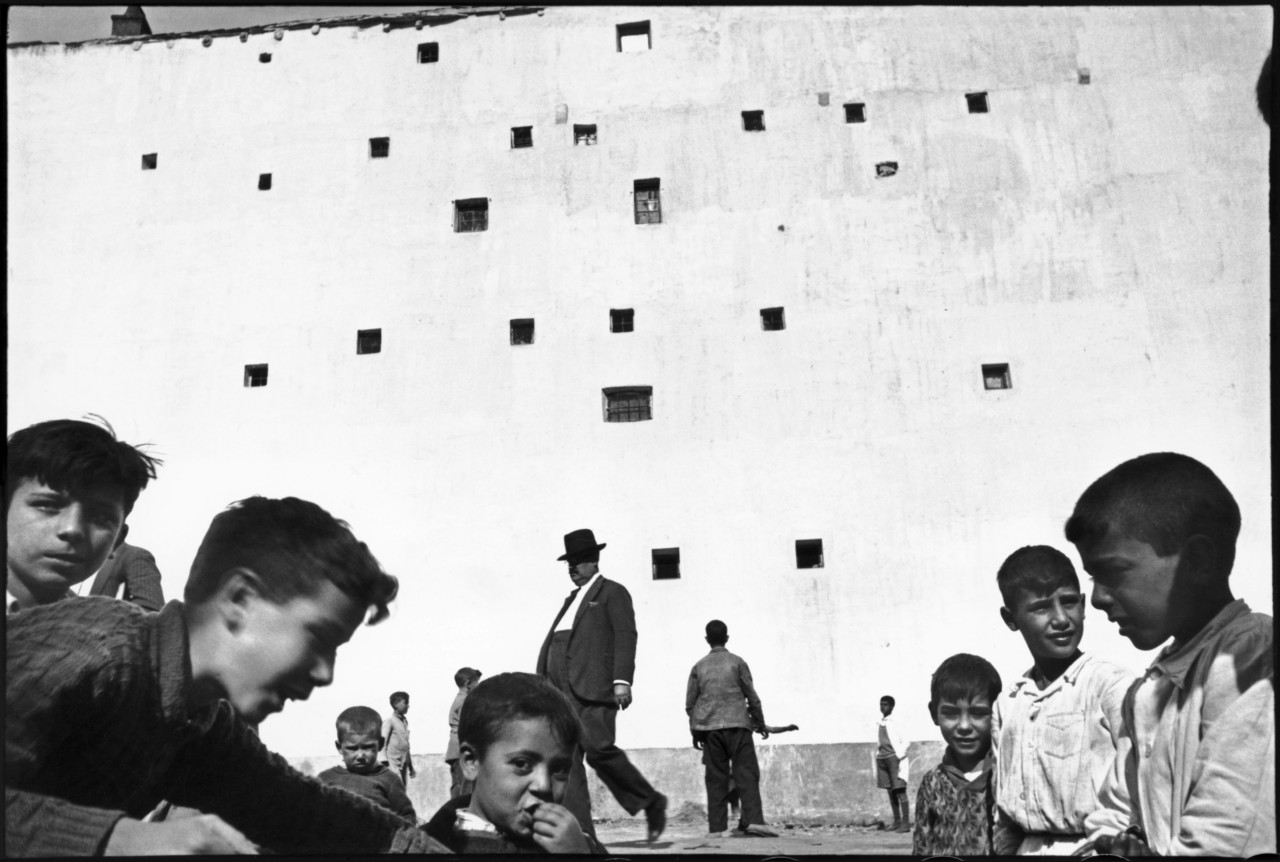

Framing & Geometry

“The genius of Cartier-Bresson, was having a frame, a notion of geometry in his brain and in his eye, which he obviously had but that he used a lot when he studied with André Lhote when he looked at paintings, and when he looked at the works of Paolo Uccello for example. He spent hours at the Louvre looking at his work. He did that all his life, and it shaped his brain. When he took a picture, the frame was obvious because that was something that came naturally to him.

That was his strength because not everyone can take a picture like, for example, the photo of Saint-Lazare, of a man jumping across a puddle, with his reflection in the puddle of water, and on the wall in the background, is a poster with a man jumping in the same position. He took this photo behind a fence without being able to approach the subject completely, which he then had to frame, and that there’s only one of them because it’s just one single moment – you truly have to be able to judge distance by simply sight.”

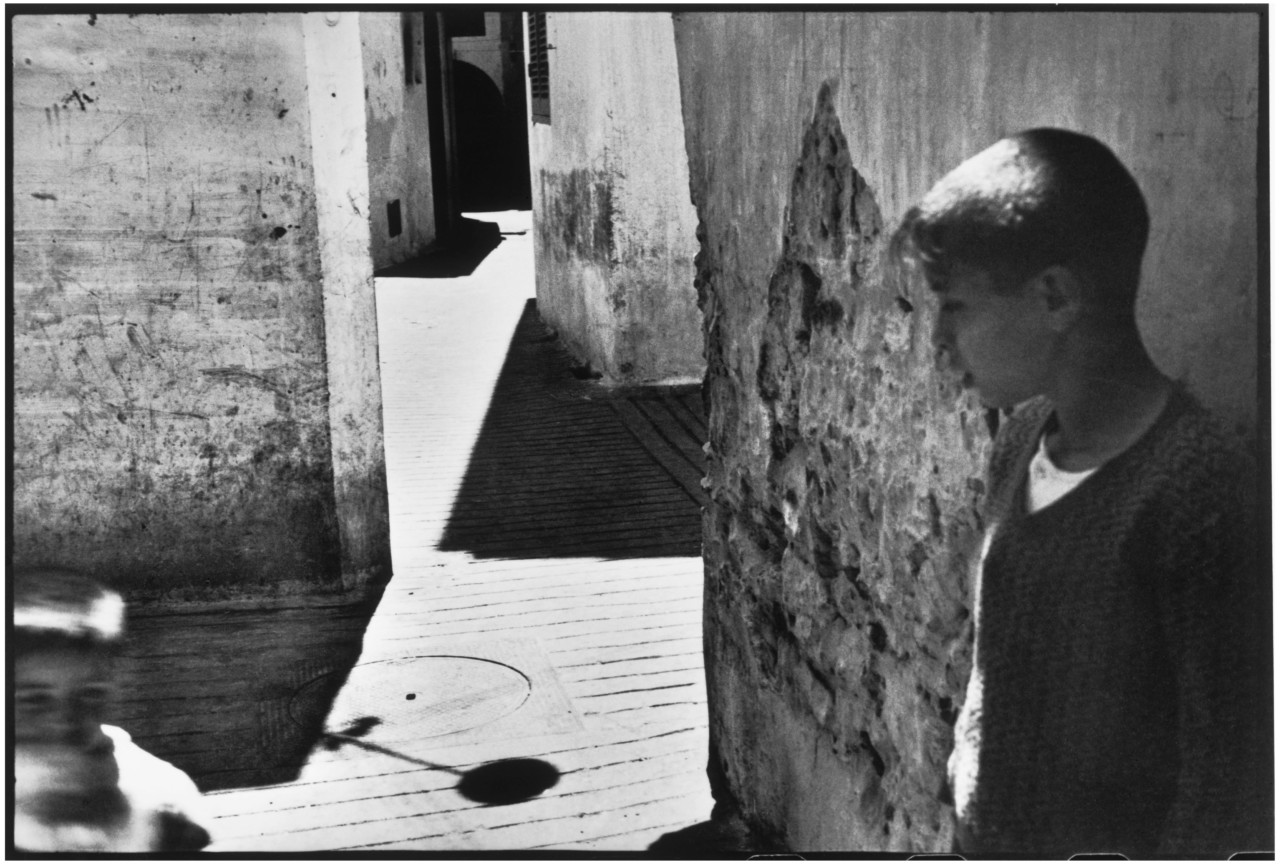

The Decisive Moment Vs Psychoanalysis

“Cartier-Bresson found the expression ‘the decisive moment’ much too limiting because he was also very interested in psychoanalysis and the subconscious. He talked a lot about what André Breton had taught him. He taught him to search through the rubble of the subconscious.

Those are some pretty important things to know. It’s not just any photographer who thinks like that, so this notion of the ‘decisive moment’ obscures all that. It’s very precise, very literal. It doesn’t take into account all the different temporalities of photography, of the subconscious, of the past, of the day before.”

The Camera as Sketchbook

“When Cartier-Bresson discovered the Leica camera in 1932, it became the extension of his eye… He never put it around his shoulder, but with a band around his wrist. It was a little bit like a weapon.

He was often asked what the camera mean to him and he would say it could be a kiss, it could be a knife cut or a psychoanalyst’s armchair… It’s clear that he still kept in mind the subconscious and aggression, because taking a picture can be aggressive. We also see that he thought of photography in a more tender sense, in symbiosis with the person when he says it can be a kiss.

He also had the tendency of saying that ‘one must approach the subject with the stealth of a wolf and velvet gloves; no hurrying’. He would say that a fisherman would never throw a stone where he wants to catch a fish in the river. You have to do the exact same thing with photography.”

More than an Observer

“Of course, you first have to have talent. If you don’t have talent, don’t bother. But, you have to cultivate talent. I think if you’re a photographer, to only cultivate your talent with photography is pretty dull. You have to read, you have to look at sculpture and paintings. That’s how you build this talent.

You have to be involved. That was definitely something that Cartier-Bresson said pretty often…You have to be engaged in what you see otherwise the photos will not be good; Otherwise, you’ll just do your job as an indifferent spectator. So talent and involvement are both things that hold a lot of weight.”

Explore Magnum’s new online learning course The Art of Street Photographyhere.