Holding Onto You: Photographs as Protest Signs

Portraits of the missing and deceased, displayed in demonstrations against state and police violence, become symbols of struggle and part of collective memory

As part of Magnum Photos’ recent Emerging Writers in Residence program, six early-career photography writers were invited to research and respond to a topic of their choosing in Magnum’s photographic archive. This text is one of the works that were produced on the residency — see all six at the link here.

Daniel Mebarek is a Bolivian artist based in Paris, France. In this text, Mebarek explores the role, and power of, the public display of photographic portraits which commemorate individuals who have been killed by police and state violence. Beginning with an investigation of the use of these images as protest signs in Latin America and in the 20th century, Mebarek goes on to explore their significance in recent racial justice movements, memory and the haptic qualities of a photograph, and the ‘afterlives’ of portraits which become iconic.

A face in the crowd. The photograph of a face to be precise. A group of demonstrators hold the portrait of Arlen Siu Bermúdez, a young woman who was killed in 1975 by the regime of Anastasio Somoza in Nicaragua and who became an emblematic figure of the Sandinista struggle. Susan Meiselas, whose work has been distinctly concerned with the social uses of photographs, captured this scene in 1978.

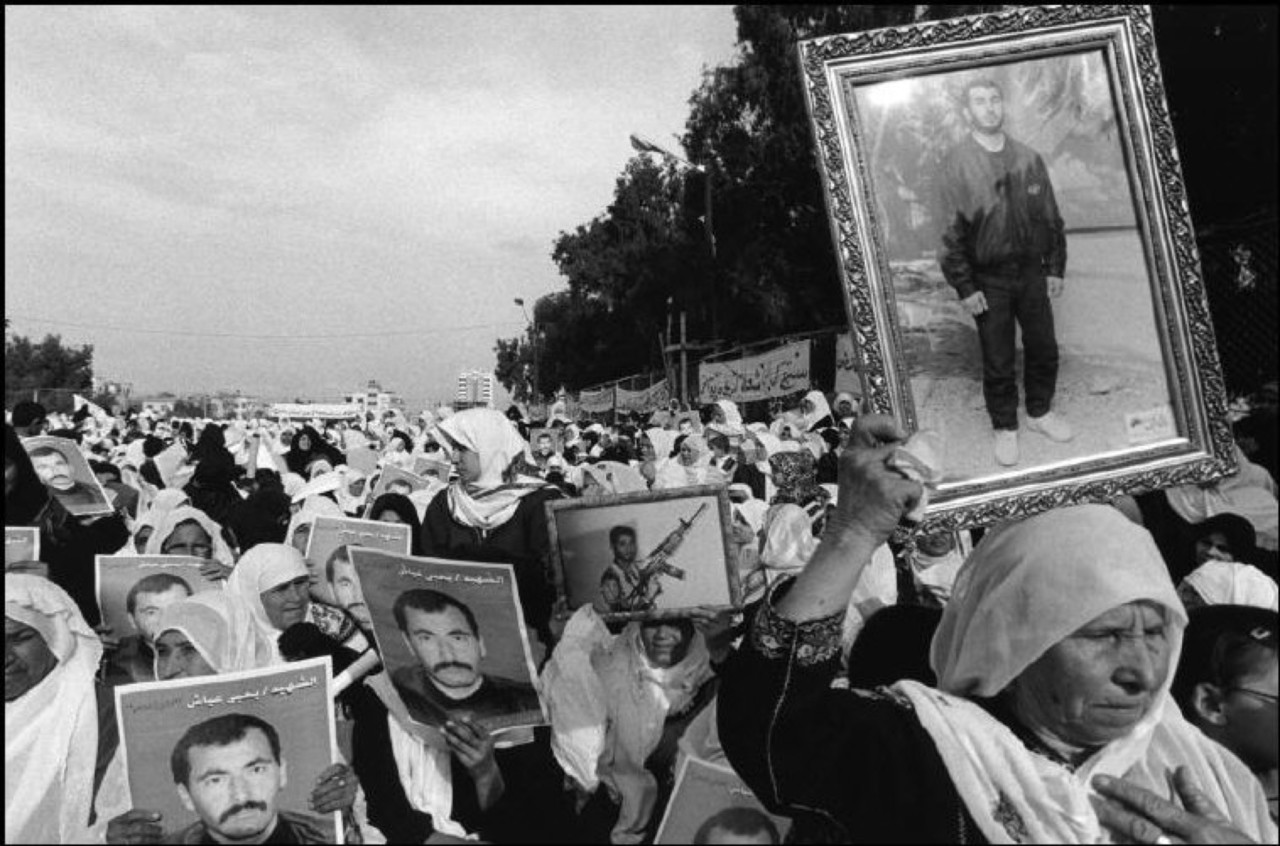

Looking at this photograph, we cannot help but be transported to recent similar scenes in the context of protests against state violence and police brutality. From Adama Traoré to Marielle Franco, and George Floyd, we see demonstrators carry their photographic portraits—their presence in the crowd appears almost spectral.

Such gestures have become so commonplace that we often neglect to notice their multiple and powerful significations. What does a photograph do when it’s held up high like Arlen’s portrait? At the most basic level, these uses of photographs bring to focus one of the core premises of the photographic medium, namely its relationship to truth.

Hannah Arendt wrote at the time of the Auschwitz trials that “lacking the truth, [we] will however finds instants of truth, and these instants are in fact all we have available to us to give some order to this chaos of horror.” For those seeking justice in the face of atrocity, displaying photographs can mark these precise “instants of truth”. Photographs hold evidentiary value; they can confirm that an individual existed, and indeed mattered, even against the forces of repression.

"From Adama Traoré to Marielle Franco, and George Floyd, we see demonstrators carry their photographic portraits—their presence in the crowd appears almost spectral."

-

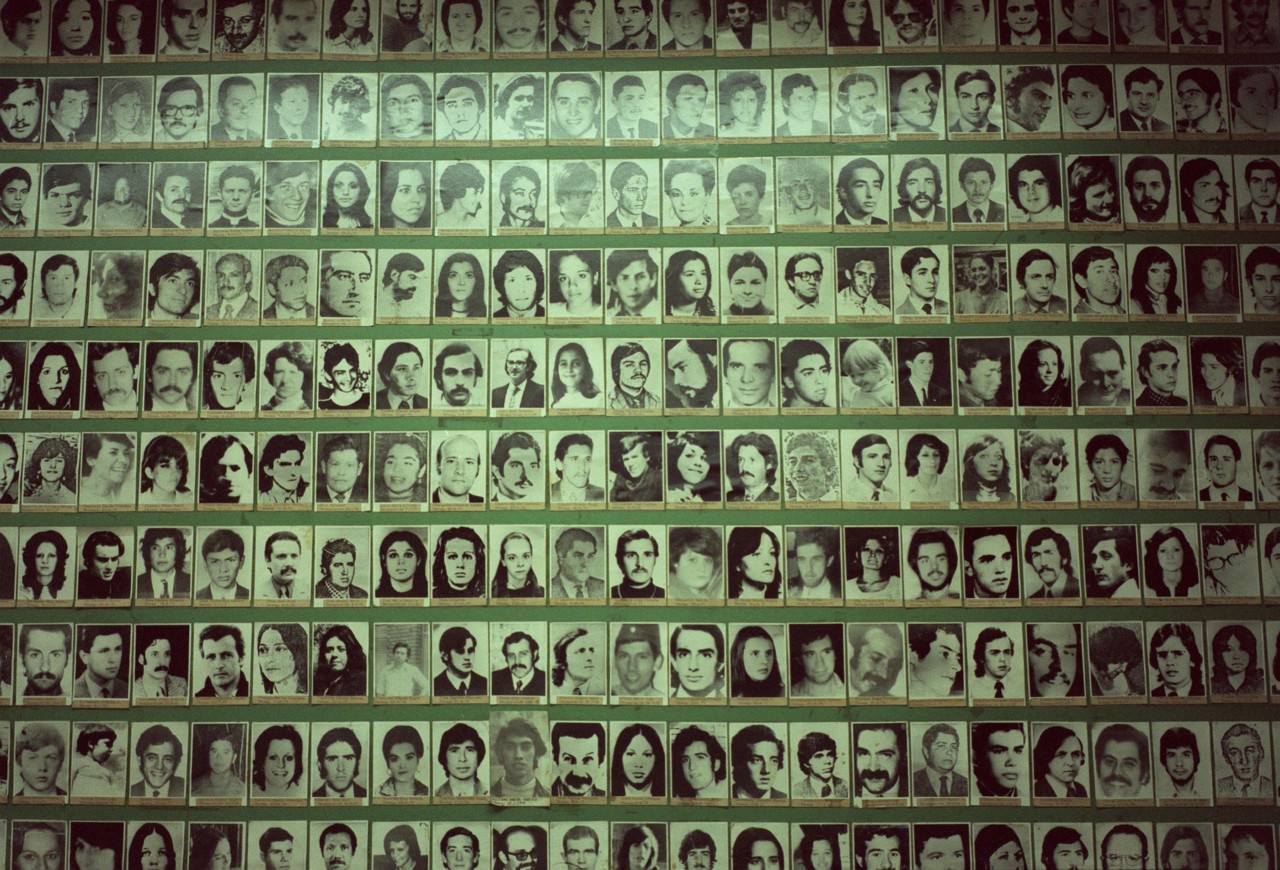

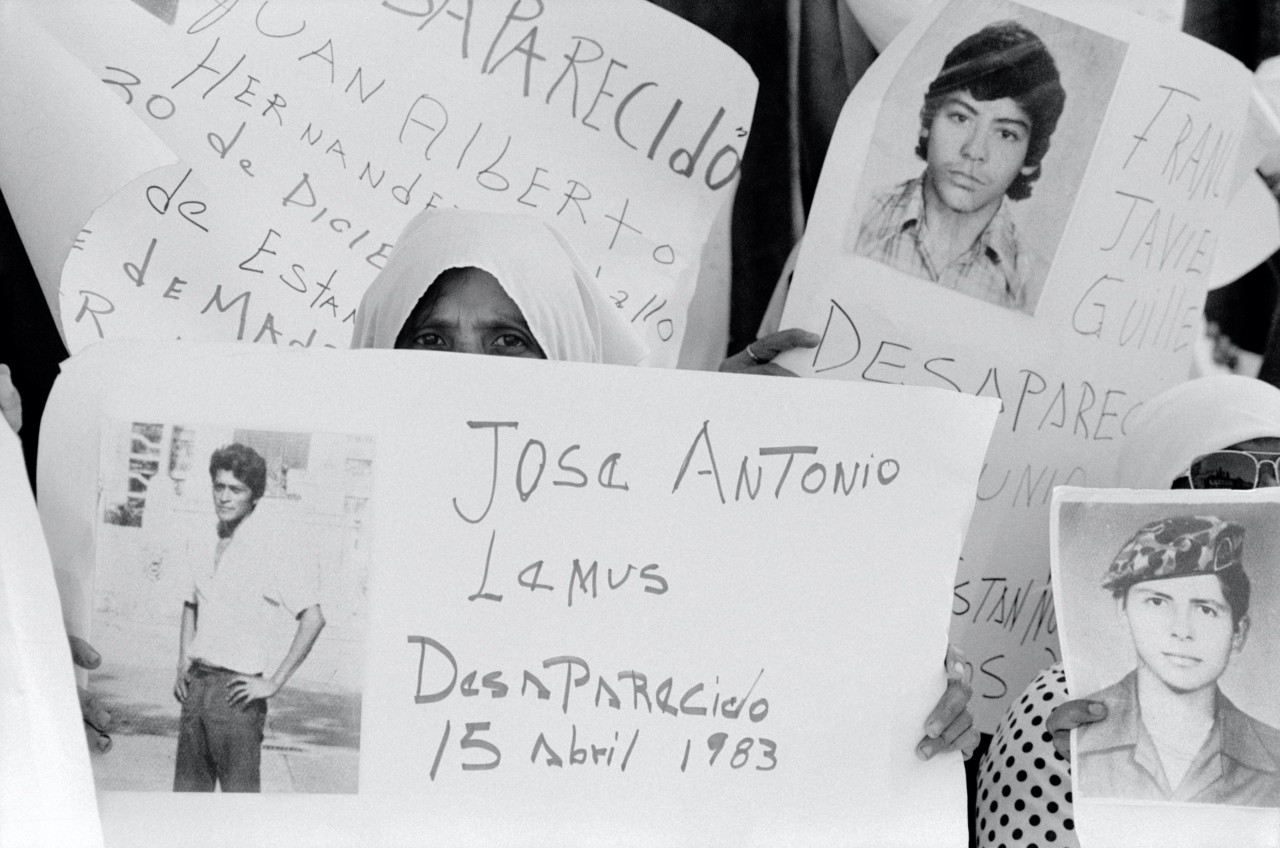

These kind of photographic uses in the public space have a prominent history in Latin America, which can be traced back to the 1970’s and 1980’s in the context of protests demanding truth and justice for the “desaparecidos” during the dictatorships.

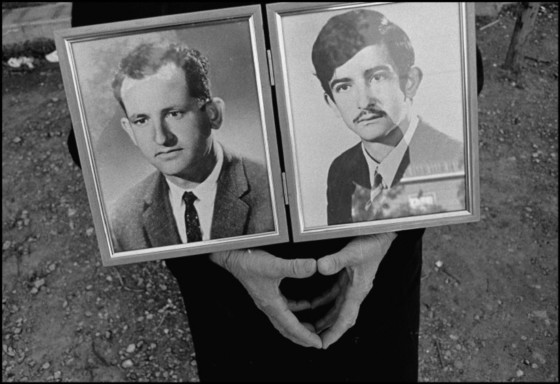

The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, as they later became known in Argentina, most notably used photographs of their “disappeared” children to accompany their political demands every Thursday at the Plaza de Mayo, the main square in Buenos Aires, during the dictatorship of Jorge Rafael Videla. This period (1976-1983) saw the forced disappearance of at least 30,000 people, including 10,000 women and 100 pregnant women.

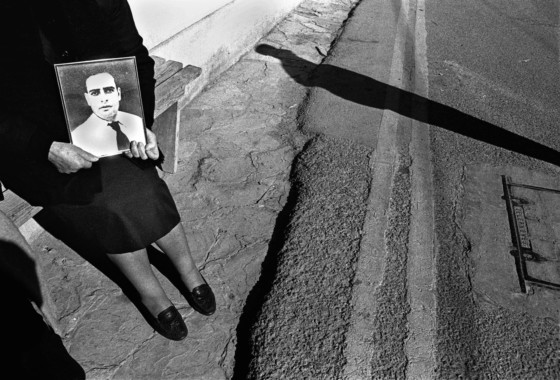

In the absence of the bodies of their children, the Mothers held tightly onto their photographs, which included family photographs but also identity photos from official documents, student IDs, library cards and trade union membership cards, among others. The Mothers initially wore these photographs around their necks before they started to enlarge them and mount them on cardboard, turning them literally into protest signs.

The repurposing of these photographs added new layers of meaning to the original images. Cultural theorist Nelly Richard has written in this context that these images, once used as family remembrances in the domestic space, “left their private rituality to become active instruments of public protest.”

If one also notes how identity photos have historically been used to classify, control and dominate individuals in the context of state, scientific or imperial motivations, the use of this genre of photographs by the Mothers, especially by displaying them against their own bodies, was particularly significant in bringing attention to the personhood of the disappeared and evoking the family ties that once surrounded them before they were shattered by the violence of the state.

Back then as now, how victims of state violence and police brutality are represented matters. In the United States, the politics of representation of Black Americans killed by the police has increasingly been pushed into the limelight.

One such example is the viral hashtag #IfTheyGunnedMeDown that started in response to the largely negative visual representation of Michael Brown in the media following his shooting by the police in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014. In these Twitter posts, pictures of Black men and women in military uniforms, medical scrubs, graduation gowns, suits and ties, are placed alongside images of the same individuals posing more casually and doing hand gestures — images they knew could be perceived as menacing. The hashtag raises the rhetorical question: If they gunned me down, what picture would the media use to represent me?

Scholar Tina M. Campt has noted that such acts can be understood as a “quotidian practice of refusing”: a rejection of the terms imposed upon Black communities — terms that create binaries and “negate the complicated truth of the lives they have lived.” In this regard, the display of images of the victims during protests can also play a part in creating counter-narratives to the dominant discourse of mainstream media and the state.

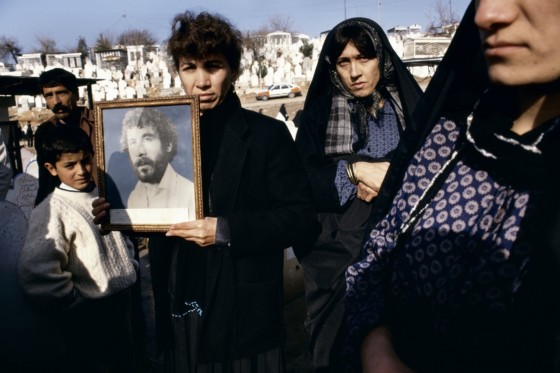

The various ways photographs of deceased or missing people are displayed, held, or worn publicly also shows the complex process in which we remember through photographs.

Photography has often been said to be a “window into the past”. As art historian Geoffrey Batchen has pointed out, this relationship between photography and memory is often underpinned by the materiality of the object itself. “It is surely this combination of the haptic and the visual, this entanglement of touch and sight that makes photography so compelling a medium,” he writes. Memory is, in this sense, not only an image but also a sensation.

As such, we may not be surprised to see photographs of victims displayed in beautifully ornamented frames, held around the neck like a medallion, imprinted on t-shirts, or, as some recent photographs show, printed on face masks, in the context of Covid-19. All of these material and presentational forms intensify the affective dimension of photographs and their associated memories.

Seeing portraits displayed during protests reminds us that photographs have a physical presence in the world and even lives of their own—they change hands, find use, and become part of rituals in different social spaces. In some cases, the images of victims may acquire afterlives through their wide dissemination and virality. Their faces appear everywhere, physically and digitally, transcending their original representation to become symbols of struggles. Like a poster of Berta Cáceres that appears at the Sioux protest camp in North Dakota, their presence in different corners of the world signal to us that our struggles are always connected.

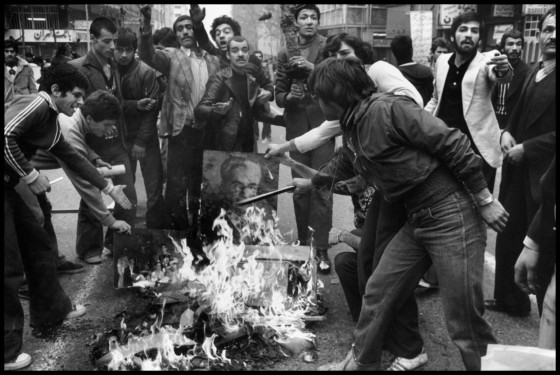

Conversely, portraits can also become symbols of oppression in specific contexts. In such cases, the display of these portraits in the public space may take a completely opposite meaning though gestures of desecration. Just like we may carry the portrait of a victim with a feeling of respect, we may also publicly burn images of political leaders as a sign of protest.

Looking again at Arlen’s portrait, the power of such displays of photographs in the public space hinges not so much on signaling the absence of someone but in making it appear that they’re still with us. This is the ambivalence that Susan Sontag referred to when she wrote that photography is a “pseudo-presence and a token of absence”. The photographs of victims haunt us because of the absent presence they point to. So, while their bodies may no longer be with us, we can still on such collective occasions say their names and embrace them with our eyes.

Daniel Mebarek, (@daniel.mebarek), b. 1993, is a Bolivian artist based in Paris, France. His work engages with questions surrounding the construction of historical narratives, memory (both individual and collective), state violence and national identity.

He graduated from Sciences Po Paris and the London School of Economics. His work has been published in Fotofilmic (CAN), Der Greif (DEU), Humble Arts Foundation (USA), Kris Graves Projects (USA) and Balam Magazine (ARG). His work was also selected for Aperture’s 2020 Summer Open exhibition held at Fotografiska, New York. He most recently co-curated the exhibition “DUST: The Plates of the Present”, a photographic installation of 1031 photograms initiated by artists Jo-ey Tang and Thomas Fougeirol, at the Centre Pompidou in Paris (October 2020-March 2021).

This project was made possible thanks to support from The National Lottery Heritage Fund.