Inge Morath Remembered

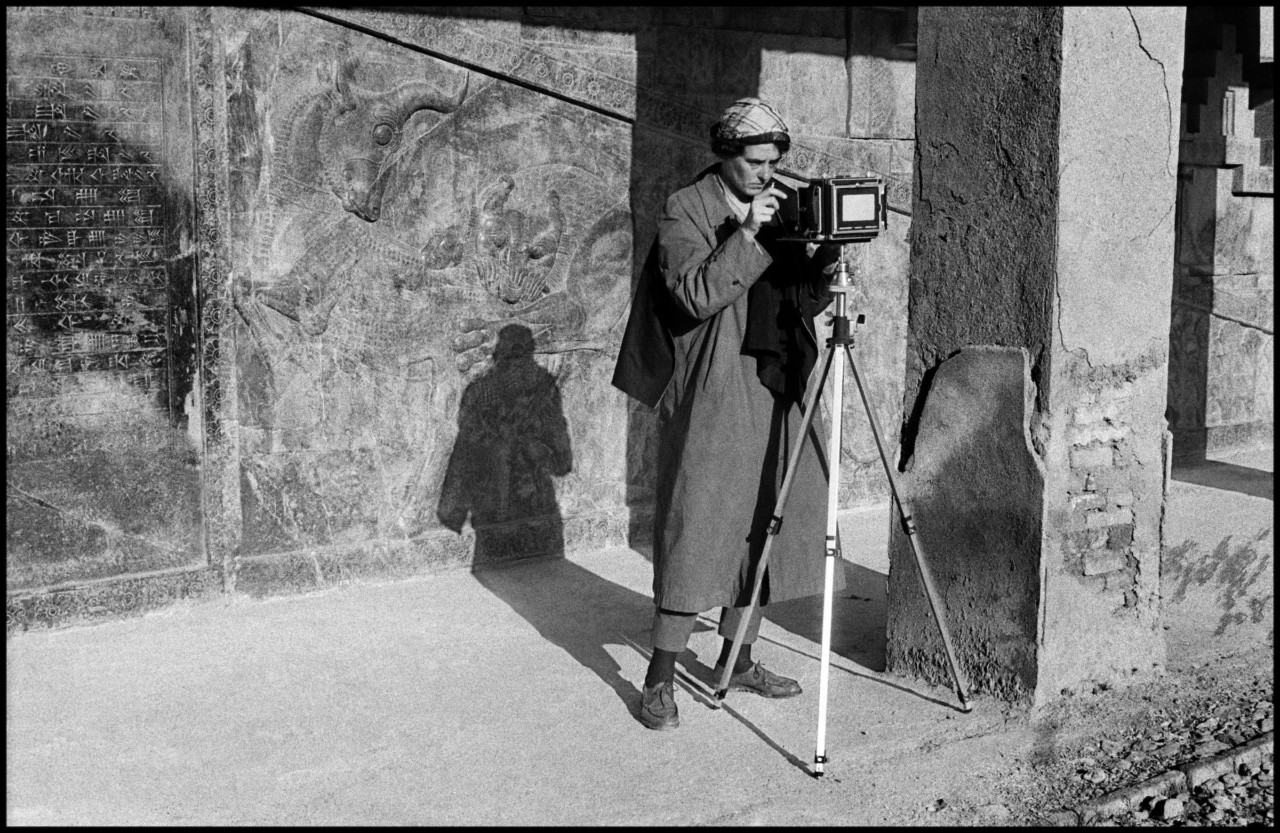

Marigold Warner recalls the life and work of the first woman to join Magnum as a full member, who was born 100 years ago on May 27, 1923.

In 1945, a Russian air raid forced Inge Morath to flee Germany by foot. She had moved to Berlin to study linguistics, but was drafted to work at a munitions factory alongside Ukrainian prisoners of war. Morath, 22 at the time, joined thousands of refugees, walking 455 miles to her parents home in Salzburg, Austria — an arduous journey that drove her to the brink of suicide.

Morath wouldn’t become a photographer for another decade, but when she did, she refused to photograph war. “Her experience of the tremendous ugliness of what human beings can do to each other marked her for the rest of her life,” says Rebecca Miller, remembering her mother’s legacy on the event of her centenary. “It also made her really appreciate what art can do, which is sort of to make sense of life, to find coherence in an image that seems chaotic.”

Born in Graz, Austria, a century ago on May 27, 1923, Morath lived in several countries throughout her life. Her parents were Nazi sympathizers, and as scientists their work took them to labs and universities all over Europe. She grew up in the shadow of Nazi Germany, and her first encounter with modern art was in 1937 at the notorious Entartete Kunst exhibition organized by the Nazi Party in Munich, consisting of 650 pieces of ‘Degenerate Art’.

The works were captioned with labels denouncing their moral and aesthetic value, in order to “educate” the public on the “art of decay”. For 14-year-old Morath, the exhibition had quite the opposite effect: “I found a number of these paintings exciting and fell in love with Franz Marc’s Blue Horse,” Morath wrote. “Only negative comments were allowed, and thus began a long period of keeping silent and concealing thoughts.” Far from being frivolous or decadent, for Morath art was essential; she later described her photographic practice as “a search for inner truth.”

After high school, Morath moved to Berlin to study languages and became a translator. She had a unique gift for linguistics, and by the end of her life she was fluent in German, French, English, Romanian, Mandarin, Spanish and Russian. A prolific diarist throughout her life, Morath began working as a journalist after the war. She became the Austrian editor for Heute, a publication based in Munich, which is where she worked alongside the photographer Ernst Haas.

In writing articles to accompany his images, Morath began to develop an affinity for working with words and pictures, and in 1949 she joined the newly formed Magnum Photos as an editor. There, she became enamored by contact sheets sent in by Henri Cartier-Bresson. “In studying his way of photographing I learned how to photograph myself, before I ever took a camera into my hand,” she wrote.

"It was instantly clear to me that from now on I would be a photographer."

-

Morath eventually picked up a camera in 1951 in Venice. A brief period of rainfall had passed, and a gorgeous afternoon light flooded the city’s rain-soaked streets. Morath was captivated. She called up Robert Capa, urging him to send a photographer to capture the incredible light. Understandably, Capa responded by telling her it was too late to send a photographer, and that she should take the images herself. So she did.

She borrowed her first husband’s (the British journalist Lionel Birch) camera, and the results were impressive. “It was instantly clear to me that from now on I would be a photographer,” she wrote. In the following years Morath continued to work on photo stories, eventually moving to Paris, where she assisted Cartier-Bresson. In 1953, after presenting her first long-form story about the ‘worker-priests’ of Paris, she was officially invited to join Magnum as a photographer. Two years later, aged 33, she became the first woman to be a full member.

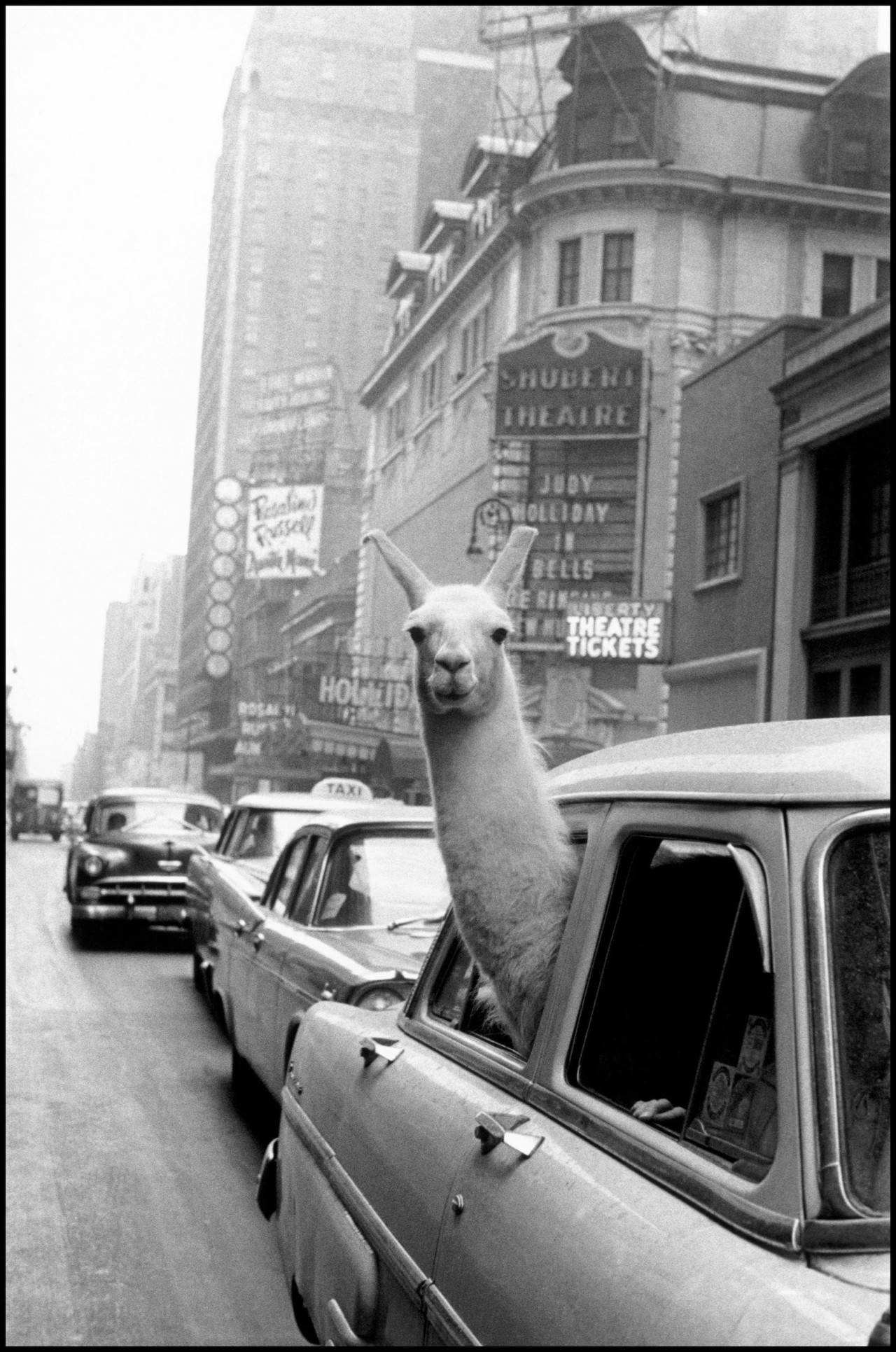

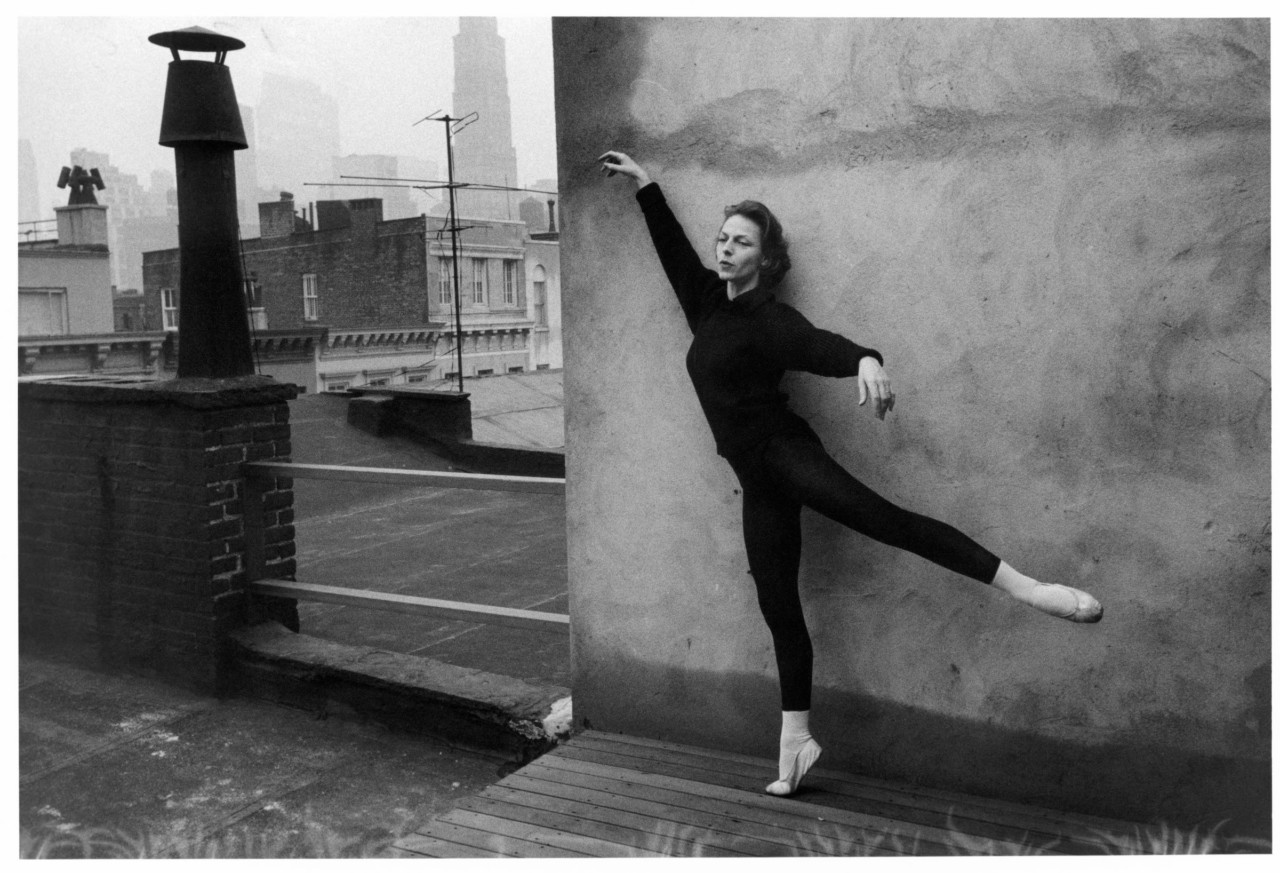

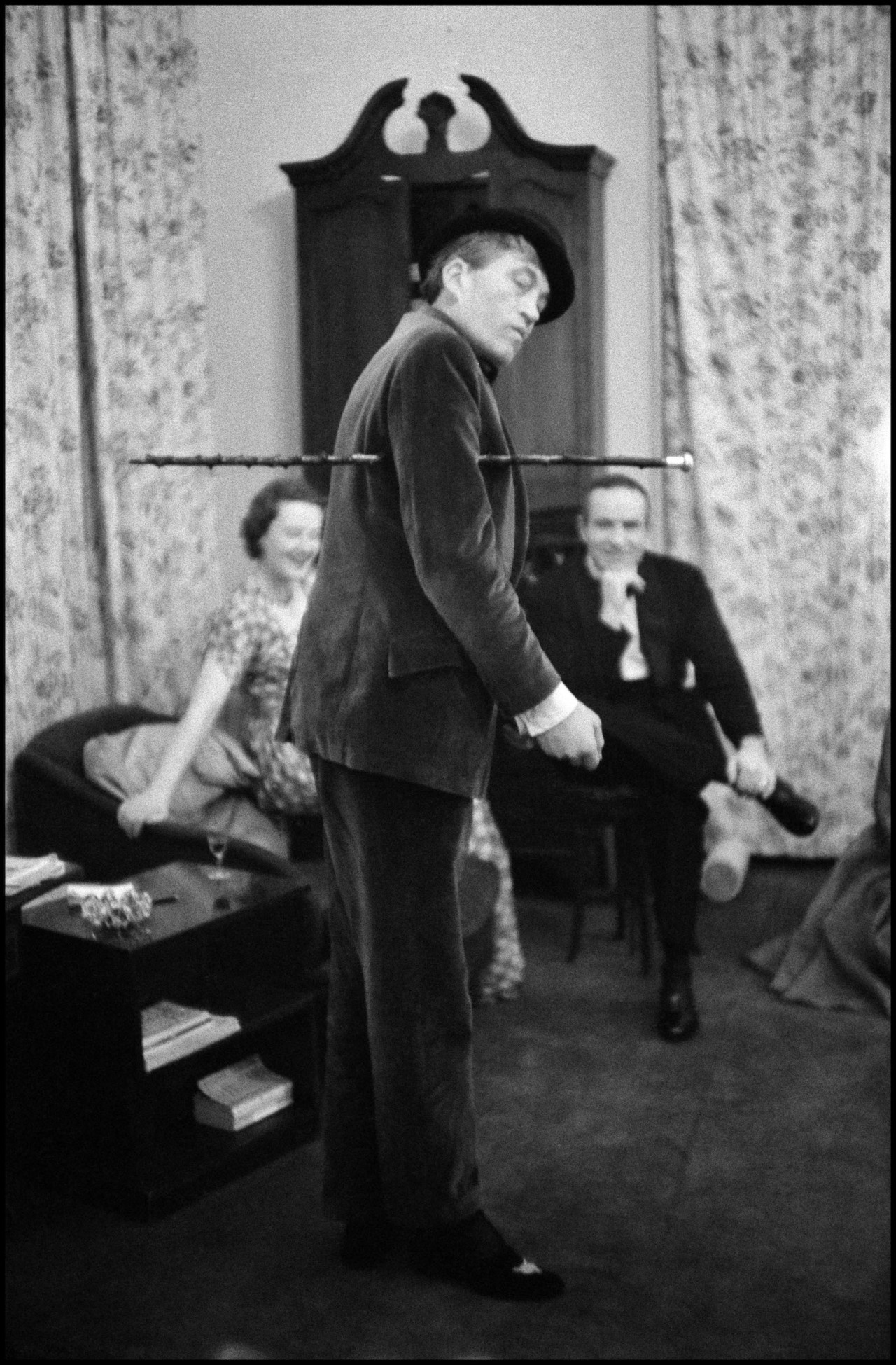

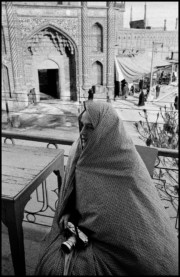

She traveled extensively in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East, and became known as a sensitive, clever and elegant image-maker — whether it was shooting fashion editorials, passers-by on the street, or sitting with world-renowned artists. She was an early pioneer of color photography (evidenced in the exhibition, Where I See Color, which opens today, May 27, and runs until July 29 at Fotohof in Salzburg, Austria), a talented technician, and an experienced editor. And her six years working with Saul Steinberg on Mask Series has been described as “one of the most quizzical and fascinating artistic collaborations between a photographer and a cartoonist in history.”

Still, some critics argue that her accomplishments have been overlooked. John P. Jacob is the Smithsonian Museum’s McEvoy Family Curator for Photography, and the founding director of the Inge Morath Foundation. “I came to understand that Morath’s work had been undervalued on its own terms,” he says. Morath worked in the company of great men — Ernst Haas, Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson — who she jokingly referred to as ‘the boy’s club’.

“The evaluation of her work has suffered from misguided comparisons,” says Jacob. “The failure of some critics to see more in her work than the shadows of her better-known male colleagues veils a sexism that is endemic to both the practice and the study of photography.”

Morath once spoke about the challenges she encountered: “Being one of the then rather rare women photographers… was often difficult for the simple reason that nobody felt one was serious… I certainly do not think that I got the same forceful male brotherhood support the men got.” But, according to her daughter, “she just got on with it… She never felt sorry for herself,” says Miller. “She was aware that there were always people who had it harder than she did.”

Morath always remained positive in the face of adversity, whether it was political or personal. As a colleague, Morath was “an empathic explorer,” says Susan Meisalas, who joined Magnum in 1976. Meisalas remembers sitting beside Morath at Magnum meetings: “[She would be] whispering ideas or laughing about how serious we all were as we faced the challenges of keeping our extended ‘family’ together.”

She was also humble. Anna-Patricia Kahn, whose Zurich gallery CLAIRbyKahn represents Morath’s photographs, recognized this quality in the markings that Morath had scrawled across her own contact sheets. Kahn has curated numerous shows from Morath’s archive over the last 15 years, including a recent retrospective at Versicherungskammer Kulturstiftung, as well as a group exhibition currently on show in Israel.

“She was an amazing editor,” says Kahn. “She had enough humility to be able to look into her own work and to see what is good and what is less good. And I think this is an exceptional quality for an artist in general.”

Morath’s archive is vast — “like a big treasure,” says Kahn. “Whenever you dig into it, you find something new.” Following her death in 2002, her family established the Inge Morath Foundation, to look after the physical archive until its eventual acquisition by the Beinecke Library at Yale University in 2014. Morath’s negatives, and a set of her contact sheets and caption books, remain actively in use at Magnum Photos, where she is still represented.

Today, her legacy is continued by the Inge Morath Estate, which coordinates exhibitions, publications and events, and the Inge Morath Award, established by the members of Magnum Photos in tribute to their colleague. Funded by the photographers, the annual $7500 grant is given to a woman or nonbinary photographer under the age of 30, in partnership with Magnum Foundation.

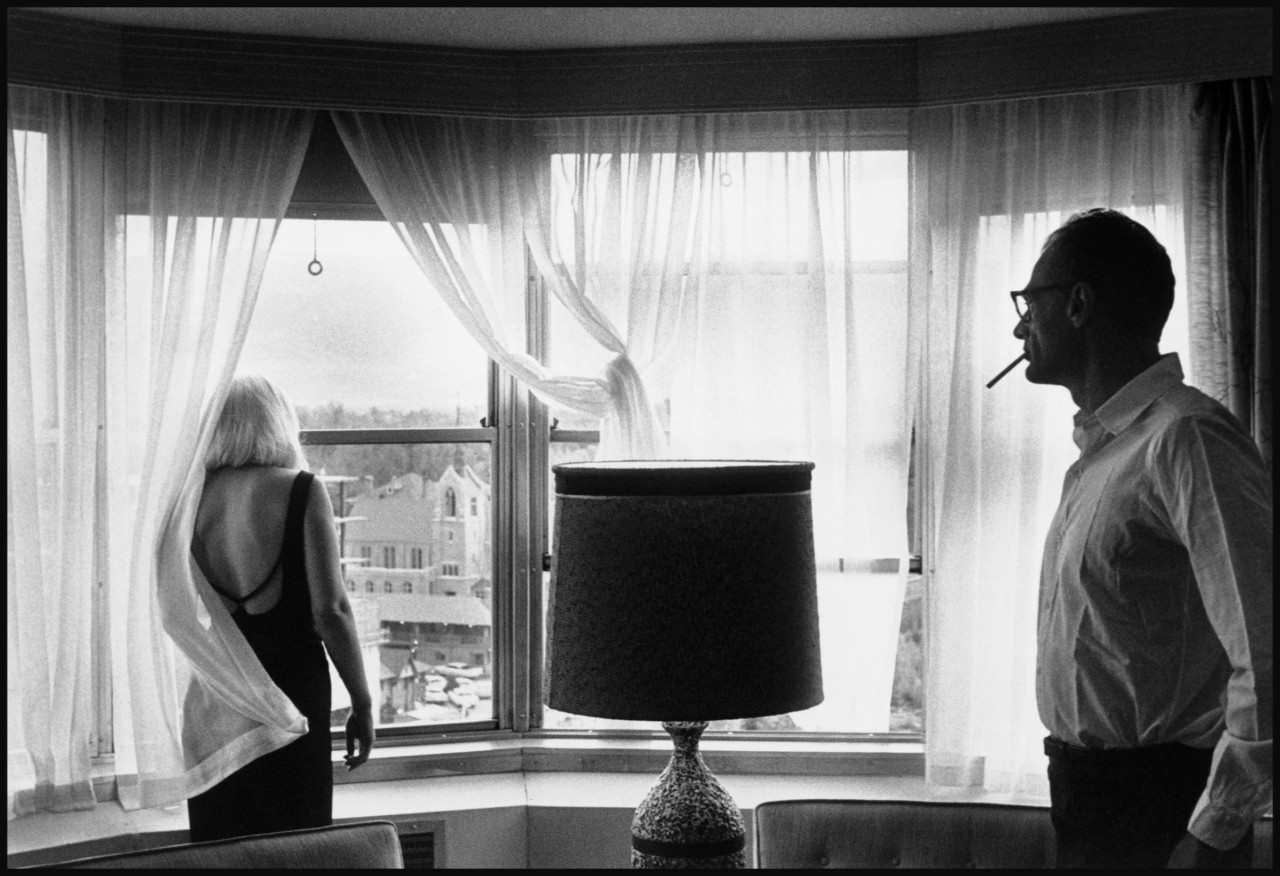

A significant part of Morath’s archive is her work as a film stills photographer. In 1960, alongside Cartier-Bresson and seven other Magnum photographers, she was commissioned to shoot on set for The Misfits, a blockbuster film starring Marilyn Monroe, Clark Gable and Montgomery Clift, with a screenplay by Arthur Miller.

At the time, Miller was married to Monroe, his second wife, but their relationship was falling apart. In a text written in 2004 and published in Inge Morath: Road to Reno (2006), Miller recalls first meeting with Morath: “When she pointed the camera she felt a certain responsibility for what it was looking at. Her pictures of Marilyn are particularly empathic and touching as she caught Marilyn’s anguish beneath her celebrity, the pain as well as her joy in life.” Following his divorce from Monroe, Miller and Morath married on 17 February 1962.

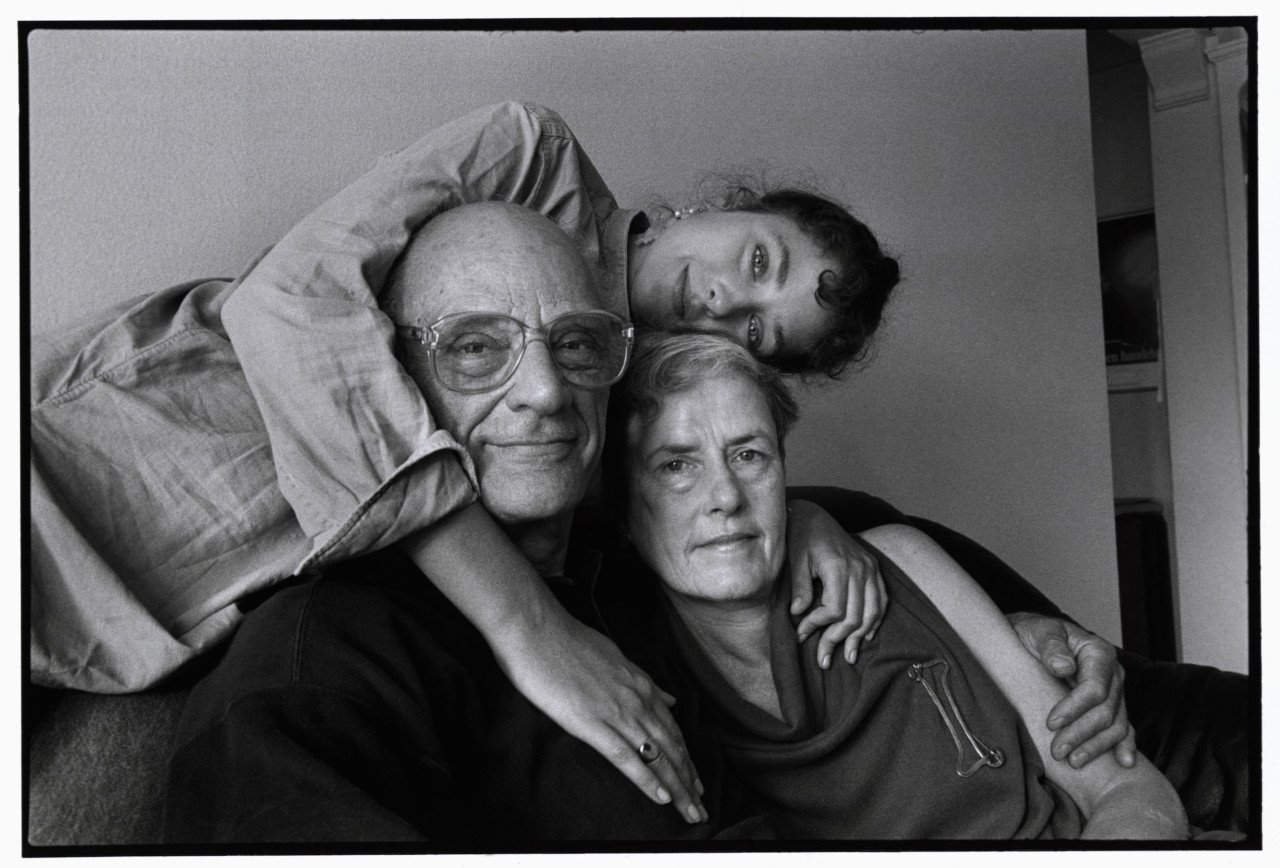

The couple collaborated on several projects together, including the book In Russia (1969) and Chinese Encounters (1979), which documented their travels through the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. Morath was disciplined and prepared extensively by studying the language, art and literature of the country she was working in. Miller later wrote that to “travel with her was a privilege because [alone] I would never have been able to penetrate that way.”

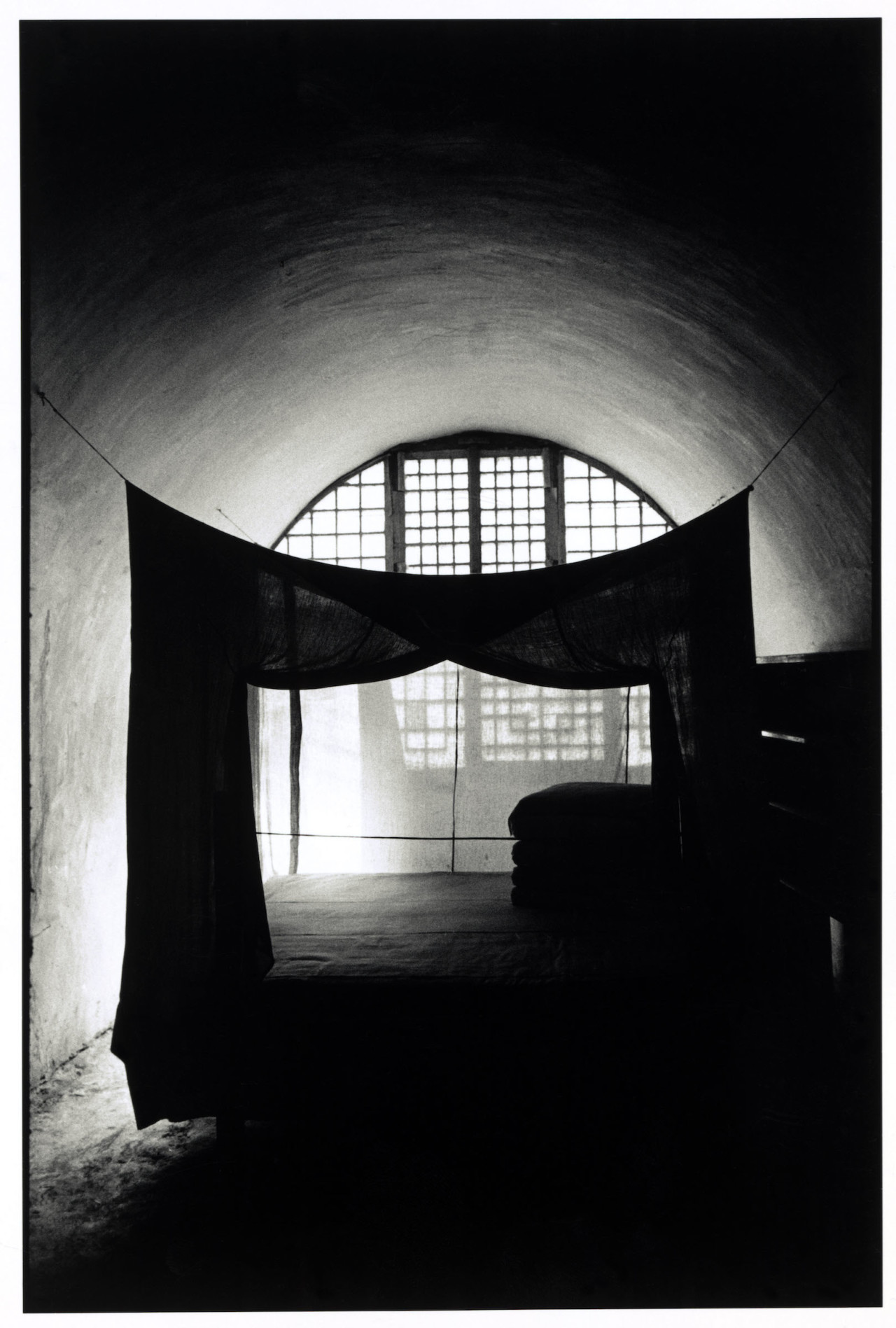

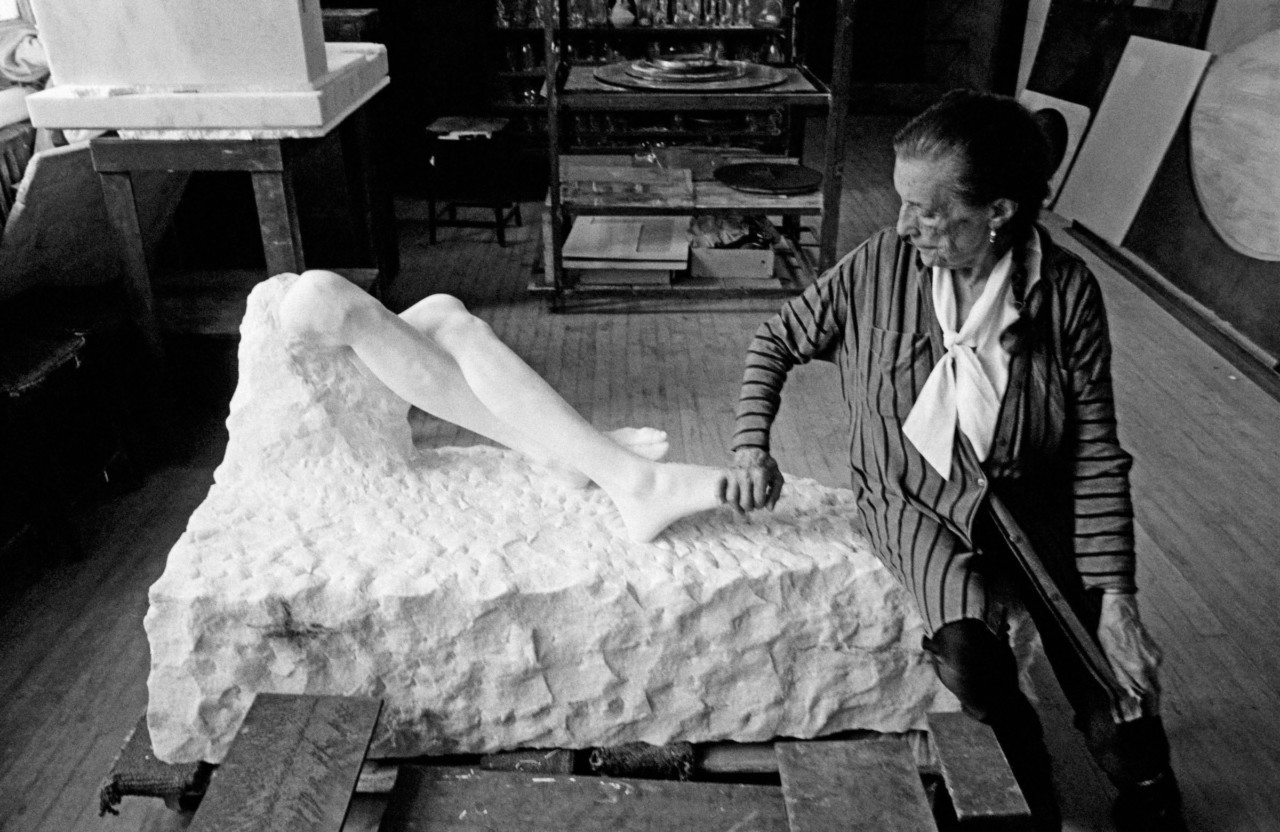

Miller’s literary network provided Morath with incredible access to artists. Some of her most iconic images are of renowned artists and celebrities, including Louise Bourgeois, Saul Steinberg, Audrey Hepburn and Alberto Giacometti. She also became known for photographing spaces, including Boris Pasternak’s home, for example, Pushkin’s library, Chekhov’s house, and Mao Zedong’s bedroom.

Morath and Miller were together for 40 years until her death. They settled in Roxbury, Connecticut, where they raised their daughter, Rebecca Miller. In looking back at her mother’s archive, Miller recognizes how so much of her work intersected with key events of the 20th century. There is one particular story that resonates with her, which she recounted during an online talk celebrating her mother’s centenary. Morath was living in Berlin in her early 20s, and had just purchased a bunch of violets from an old lady on the street. Suddenly, an air raid struck.

“For some reason, she held the violets over her head as she ran down the street, as if they were going to protect her from the bombs that were falling,” says Miller. “To me, that is so classic of my mother, because they were something that was beautiful, that might protect her… She thought of art as a protection from violence and ugliness.”

Driven by curiosity and empathy, even in the face of hardship, Morath was always searching for beauty — her photographs are proof of this pursuit. And in the beauty that emanates from her images, Morath’s spirit lives on.

…………………………………………………….

Inge Mortath was born May 27, 1923, and in honor of her centenary, there are numerous celebrations of her work:

Inge Morath – Wo ich Fabre sehe/Where I See Color

Fotohof, Salzburg

May 27 to July 29

Inge Morath – Hommage

A catalog to accompany a recent retrospective at Versicherungskammer Kulturstiftung is published by Schirmer Mosel.

Mask and Face. Inge Morath and Saul Steinberg

Museum der Moderne Salzburg

Until June 4

Inge Morath. Fotografare da Venezia in poi

Museo di Palazzo Grimani, Venice

Until June 4

Documenting Israel: Visions of 75 Years

Featuring Inge Morath’s work alongside that of Micha Bar-Am, Robert Capa, Thomas Dworzak, Bruce Gilden, Erich Hartmann, Nanna Heitmann, Sigalit Landau, Helmar Lerski, Inge Morath, Benyamin Reich, David Seymour and Patrick Zachmann.

Museum of Tolerance Jerusalem

Until June 30