Inge Morath’s Venice

In this long-unpublished essay, the photographer reflects on the allure of the city, its hidden gardens and waterways, and the role it played in sparking her photographic career

Following a recent retrospective exhibition of Inge Morath’s work in Treviso, Italy, a new book – Inge Morath. Her Life. Her Photographs. – offers a survey of the Austrian-born photographer’s career. More than 150 images spanning her key projects are accompanied by two essays by the photographer. One is her well-known text titled ‘Meeting Magnum’, the second is about Venice.

In particular the latter text explores the pivotal role the city played in her first taking up photography, in 1951, and her exploration of its myriad canals, bridges, and private gardens in 1955 while on an assignment for L’Oeil. This text was, until the book’s release, never before published.

Here we reproduce Morath’s musings on the city – its allure, mystery, and perhaps above all its pivotal place in catalyzing her love of photography, propelling her from enthusiast to practitioner. The text is accompanied by a selection of her photographs of the famed city made during that 1955 assignment, only a few years after her first, life-changing first visit.

More information on Inge Morath. Her Life. Her Photographs., can be found here.

Venice is where my passion for photography first gripped me. I’d never taken my own photographs before that. I’d looked at plenty of photographs and had occasion to judge a few, and I’d even worked with photographers. However, the written word was definitely my medium. In 1951 I was travelling to Venice. I even had a camera with me, a gift from my mother. For the longest time it had been screwed onto the top of her microscope, but she now had a new one. I didn’t really know how to use it; it got lost, and yet somehow, I always managed to get it back. Even in Naples, where I’d left it in a taxi, the driver brought it back to my hotel.

It was raining in Venice. The light was incredibly beautiful, and suddenly I was convinced of the need to photograph it: someone had to photograph it. I called up a few photographers. No-one was interested. Bob (Robert) Capa in Paris simply said, “Why the hell don’t you take a picture yourself, you idiot?”.

I went to a photo shop and had them put a roll of film into my worn-out Contax. The assistant advised me to wait until the rain had stopped before taking photographs, which I thought was idiotic; after all, I’d been around photographers long enough to know that they worked even in the rain. What’s more, the leaflet inside the box said, “1/50th with aperture 5.6 in dull weather”. Naturally, I didn’t have a light meter, and this was well before automatic cameras.

"The light was incredibly beautiful... someone had to photograph it. I called up a few photographers. No-one was interested. Bob (Robert) Capa in Paris simply said, 'Why the hell don’t you take a picture yourself, you idiot?'"

-

I was all excited. I went and stood in the spot where I wanted to take my photographs, a street corner where people went past in a way I found interesting. I adjusted the camera and pressed the release as soon as everything was exactly the way I wanted it. It was like a revelation. To realize in an instant what had been simmering away inside you for so long, capturing it the moment it took on the shape I felt was right. After that, there was no stopping me. I went everywhere, standing on bridges, in church entrance, on corners that looked promising. And then there was no film left. I bought another and decided there and then to become a photographer. I kept the decision a secret because it seemed ridiculous, and everyone knew I never took photographs. I had to find my own way by whatever means, serve my apprenticeship by myself. It took roughly a year, and it was difficult, and good. In 1955, four years after I’d taken those first photographs, I was given an assignment by L’Oeil, an art magazine for which I’d started taking artists’ portraits. “Mary McCarthy is in Venice writing a book for us. We need a photographer who can find views of Venice that match the backdrops painted by the venetian artist that Mary is writing about. Are you interested?”

Soon I was on a train from Paris to Venice. I didn’t know anyone in the city, and I’d been told the writer Mary McCarthy could be difficult. I don’t recall how I got from the Stazione Santa Lucia to the small pensione I was booked into. The room was very small, with a greenish tint, and it smelled of mould. I would have to look for something else. But first I had to set off and explore the city, and so for hours I’d walk around aimlessly, just looking until I was obsessed by the sheer joy of seeing and discovering a place. I had of course devoured books about Venice, painting and history in preparation. My inner reservoir was filled.

"Walking down the alleyways in the Fondamente Nove and looking up, I could see laundry flapping on washing lines tethered from one chimney stack to another, each as if borrowed from a Carpaccio painting"

-

At the appointed hour and with butterflies in my stomach I met the formidable Mary McCarthy at the Café Quadri, deep in conversation with the legendary Bernard Berenson. She was beautiful, with her hair brushed straight back, a very clear profile. It bothered me that I was interrupting their conversation, so escaping seemed like the best option. As quickly as I could, I said, “I’m Inge Morath, and perhaps it’s just best if you tell me what you want from my photos. Then we can meet again in a week or so and take a look at the work, OK?” I added that Georges Bernier from L’Oeil had told me more or less what it was about; also that I still didn’t know where I was staying, so perhaps she should give me her phone number. She did so, and then resumed her conversation with Berenson, seemingly relieved that I wouldn’t be detaining her any further.

"Somewhat aimlessly I walked across the bridge to the rather empty Zattare Promenade on the other side of Grand Canal to calm myself by looking at the view across the wide canal to the Giudecca, where Leonardo is said to have painted Mona Lisa"

-

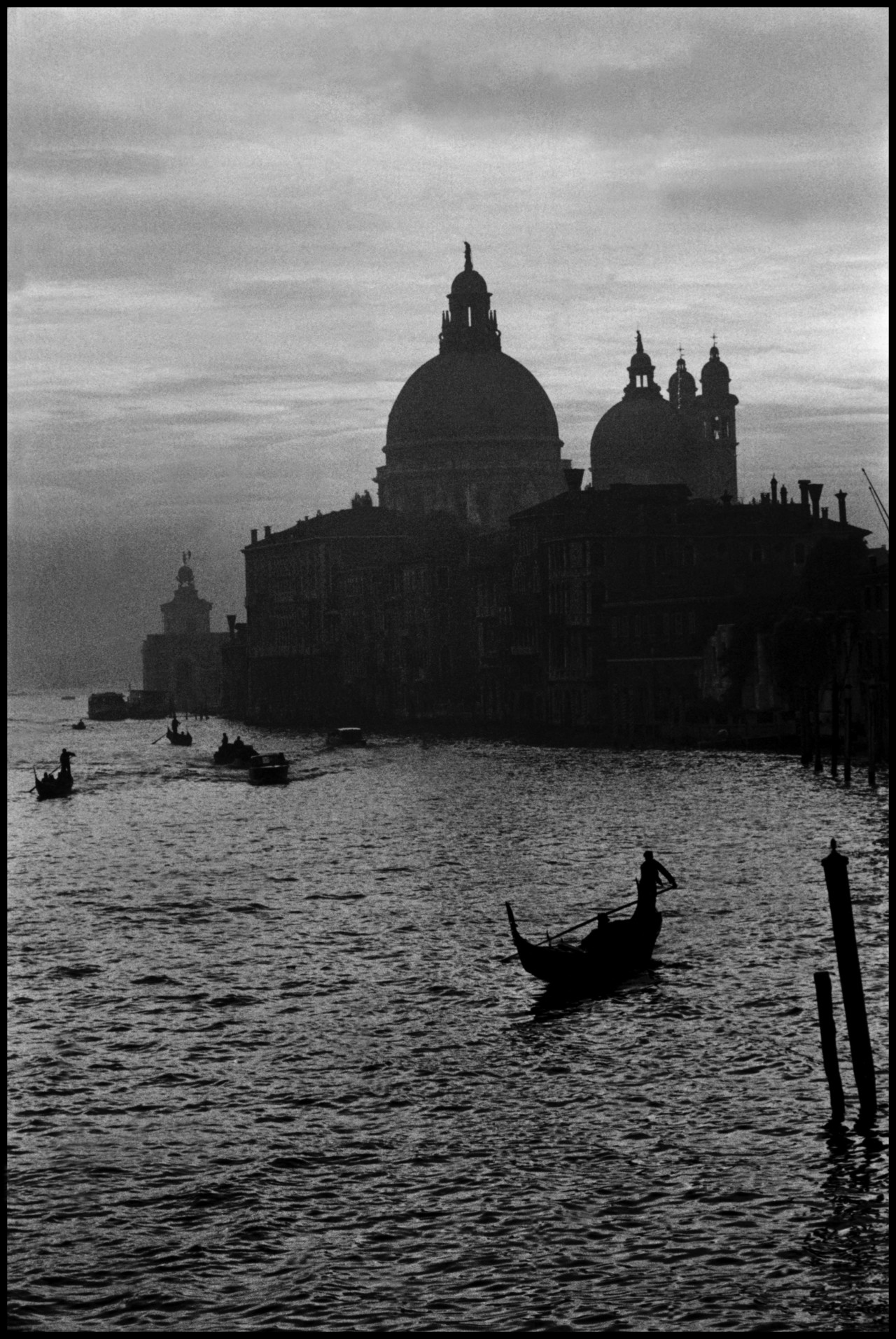

So now what? Somewhat aimlessly I walked across the bridge to the rather empty Zattare Promenade on the other side of Grand Canal to calm myself by looking at the view across the wide canal to the Giudecca, where Leonardo is said to have painted Mona Lisa. Sitting on a landing stage jutting out into the canal was a painter in a blue-yellow straw boater, his legs dangling from the piece. I took his photograph, even thought he had nothing to do with my theme. He saw me, and I explained I was taking photograph for a book. Also, that I was interested in what he was painting. He packed up, came up onto the quayside, and introduced himself: ‘Bobo Ferruzzi’. The painting was nice, with bold colours and a lightness influence perhaps by Tintoretto. Bobo offered to accompany me on a few of my Venetian forays. He loved his city and knew of a thought and nooks and crannies no stranger could ever know. His father was a well-known antiques dealer, and his mother was descended from the ancient Venetian Balbi dynasty.

What a huge stroke of luck I had had. Bobo found me a better pensione; and he knew of palazzi along the grand canal with empty rooms, their windows opening up onto unusual views. He showed me secret gardens behind the Palazzi (one of the most beautiful belonged to his father), and he loved talking about painting. As each of us was in love with someone else, our mutual attraction was based on an unstrained friendship, with just enough appeal never to be dull. A little buzz in your blood is never a bad thing when taking in Venice.

"It was delightful; we gondola-ed our way down countless canals, past gondola workshops, open windows with women mending mattresses, moorings with funeral gondolas, narrow streets, and fish markets"

-

A week later I met Mary McCarthy at her rented apartment. The first thing that struck me was a goldfish bowl containing very pale and rather tired looking fish. According to Mary, the signora maintained that the fish lived best off coins tossed into the water. We say down in a large room with a very beautiful stucco ceiling. Several pieces of furniture were covered with antimacassars. Lots of things were lopsided – the casual negligence of nobility. I showed Mary my photographs, which in the meantime I’d had enlarged, and she was satisfied. We met up now and again in San Marco, talked about painting and architecture, and sometimes about America, of which I know so little; Mary was so very American.

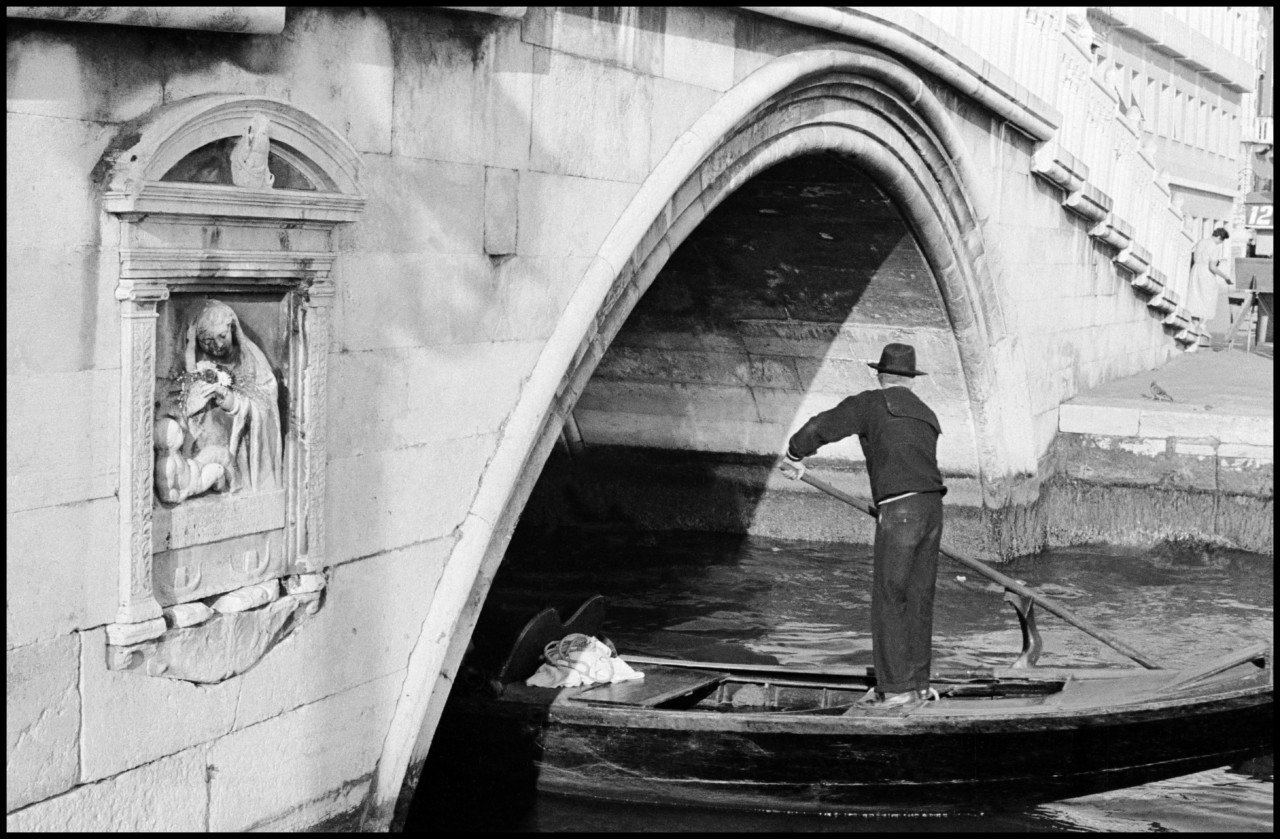

The duena at my pensione knew a gondolier. I’d previously told her I wanted to take photographs from the water. He was willing to give me a good price for a whole morning or afternoon. It was delightful; we gondola-ed our way down countless canals, past gondola workshops, open windows with women mending mattresses, moorings with funeral gondolas, narrow streets, and fish markets. Of course, we also steered our way down the grand canal with its pesky motorboats. On one occasion I even visited his family. I can’t recall how many people were living in that small house near the Fondamente Nove. On the ground floor they were making glass beads, young girls hunched over Bunsen burners. Outside, women sat unravelling wool, knitting and knitting till the last of the evening light.

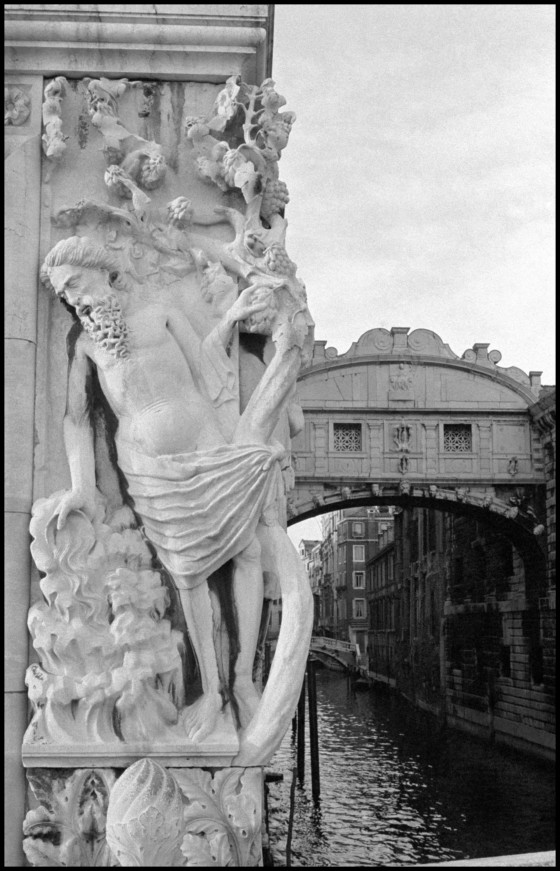

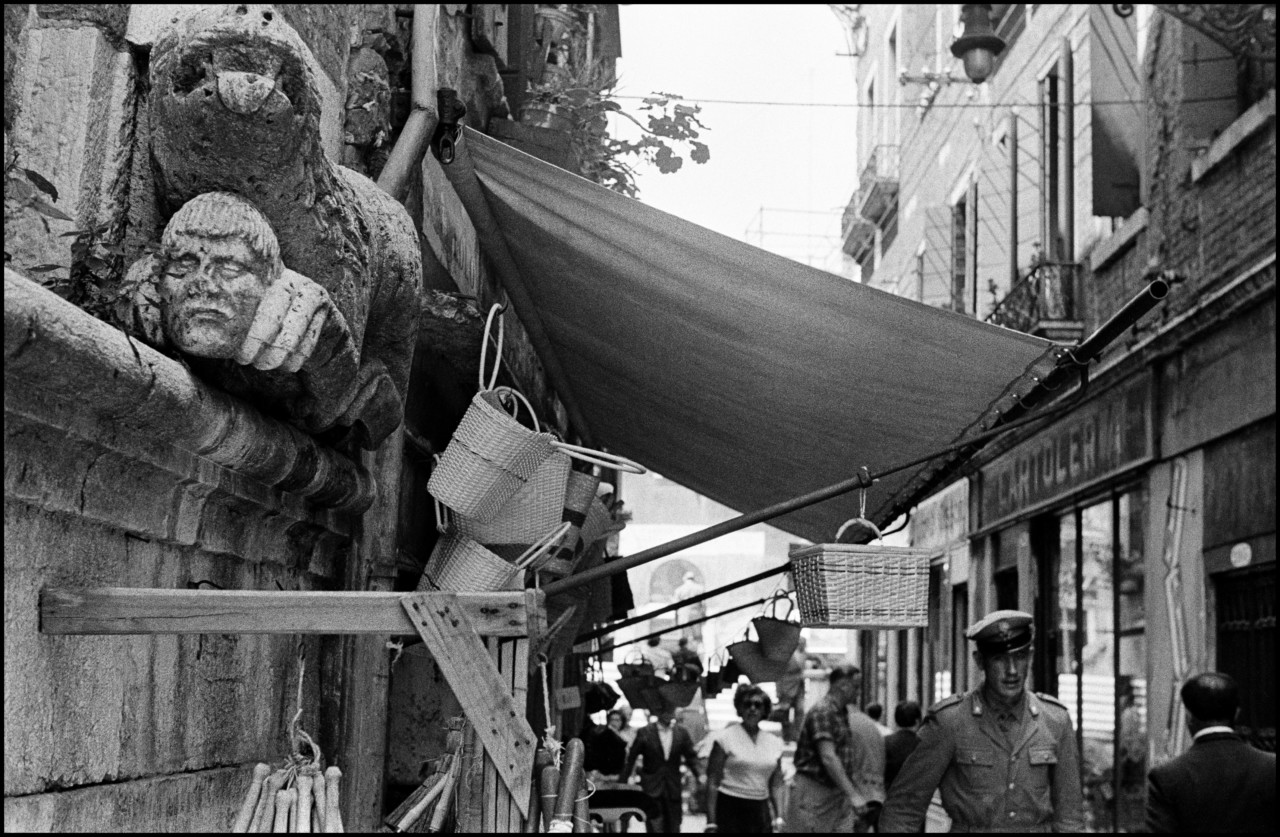

Walking down the alleyways in the Fondamente Nove and looking up, I could see laundry flapping on washing lines tethered from one chimney stack to another, each as if borrowed from a Carpaccio painting. The windows everywhere were proportioned with noble elegance, the low-set doorways marble-framed; statues all about brought street corners to life, like the turbaned moor seemingly squinting at a woman’s swirling skirt as she walks past. Cats everywhere, stretching, peering from recessed windows, huddling in mewing bundles around feeding bowls.

Inside the museums it was often quite dark, and your eyes took a while to adapt, which was good as it forced you to look closely. Titian, Tintoretto, Bellini. I enjoyed nothing more than sitting in the Scuola degli Schiavoni, immersing myself in Carpaccio. I was almost always on my own. Or spending time in the company of Tiepolo, and the end of the world.

By the evening my feet felt tired, and even in my sleep I found myself still walking across countless bridges, the waves of the canals now turned to stone.

There is no end to exploring Venice. Bobo showed me the old ghetto and the new; tall buildings; a synagogue; children on a merry-go-round. I found myself in all sorts of kitchens, with women seated outside. I scootered about on Bobo’s vespa to villas in the Brenta Valley. Marble statues rising from trimmed boxwood hedges, weeping willows framing the Villa de la Malcontenta. Who was she, I wonder, the malcontent behind the Palladian façade?

I walked alongside a gondola as it slowly rowed its way to the San Michele cemetery with a coffin and wreaths. I happened upon a vaporetto stop just as a boat was casting off for Burano, and hopped on board.

Burano was like a rustic Venice: small canals, low-built houses, all brightly coloured. It was fish-market day, with wares laid out on coarse wooded trestles: the trading and bartering and arguing. A young girl sat in a barque waiting for buyers for her roasted pumpkin seeds. Young lace-makers demanded I buy their lace before photographing them, and they were right, of course. Two men were playing cards beneath a canvas hanging above the alley like a giant sail. A restaurant served a wonderful unforgettable risotto con vongole. On the wat back I alighted at Torcello and spent a long time sitting in front of the incredible golden mosaics.

There was still plenty of work. Processions, the Festa del Redentore, for which they constructed a special pontoon bridge from Santa Maria della Salute across the Grand Canal to the Piazza San Marco. Then, late in the evening, firework displays that exploded into the bight in honour of the Redentore; families in boats and gondolas clustering along the Giudecca Canal, picnics on board.

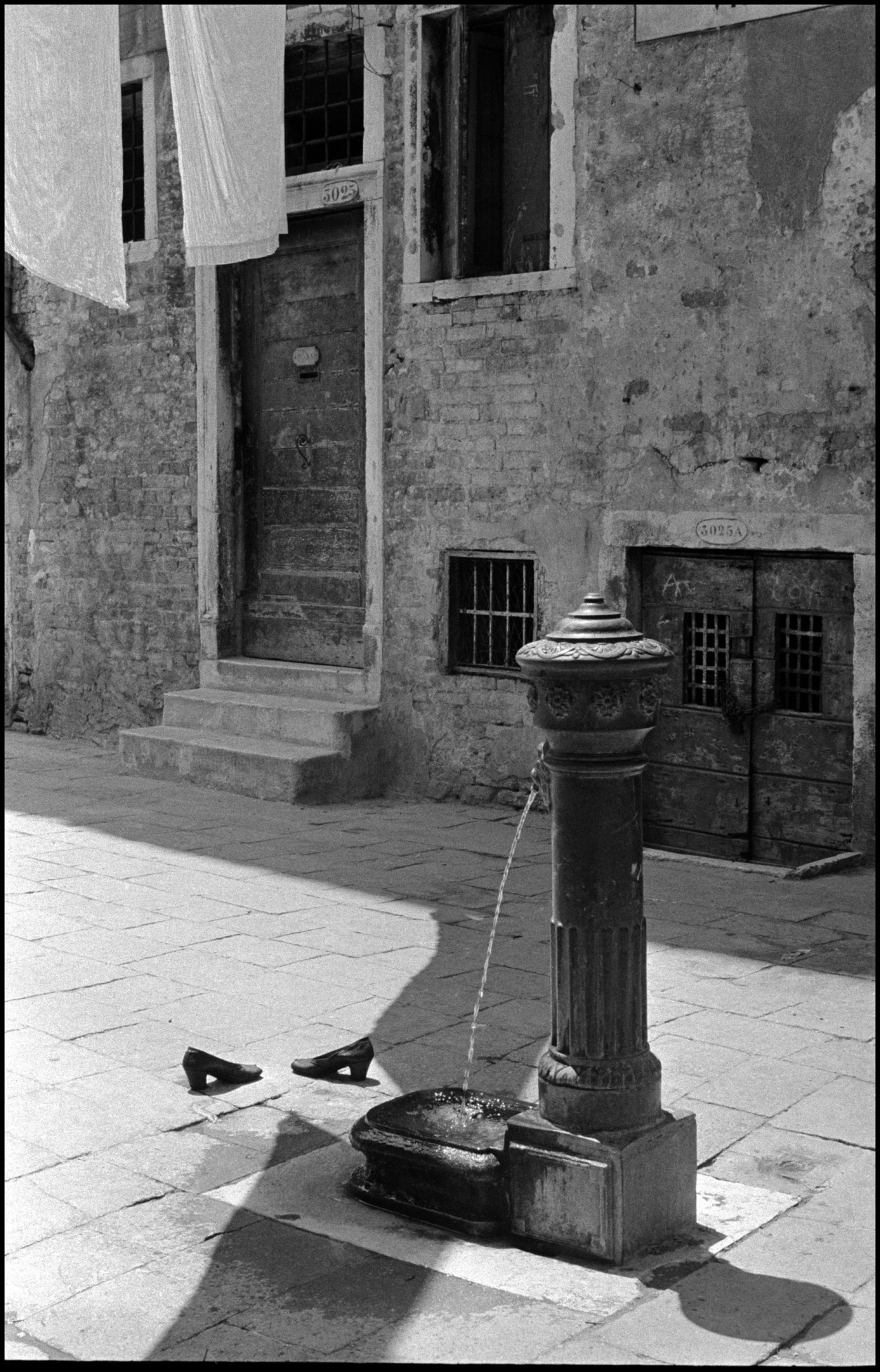

My train left early in the morning. Of course I shall return, I am not finished, not by any means. How delighted I would be to have captured with my camera something that moved me, like the woman in front of the gate of the Furstenberg Palace, her elbows folded behind her back, or the shoes forgotten in front of a fountain, everyday life in all its precarious beauty.