Jacob Aue Sobol: Close Enough to Make a Portrait

The Danish photographer discusses the closeness required to create good portraits, and life after photography

As he prepares to judge the inaugural Portrait of Humanity Award, by 1854 Media, publisher of British Journal of Photography, and Magnum Photos, Jacob Aue Sobol discusses portraiture as an integral part of his practice, and what he’s focusing on now, following his announcement earlier this year that he’s retiring from photography.

Enter the Portrait of Humanity award here.

Your work comes from a personal place, even when it features people you didn’t previously know, as with your work in Bankgok. Could you explain how you manage to get to a point where you have a good enough relationship with your subject to create a portrait you are happy with?

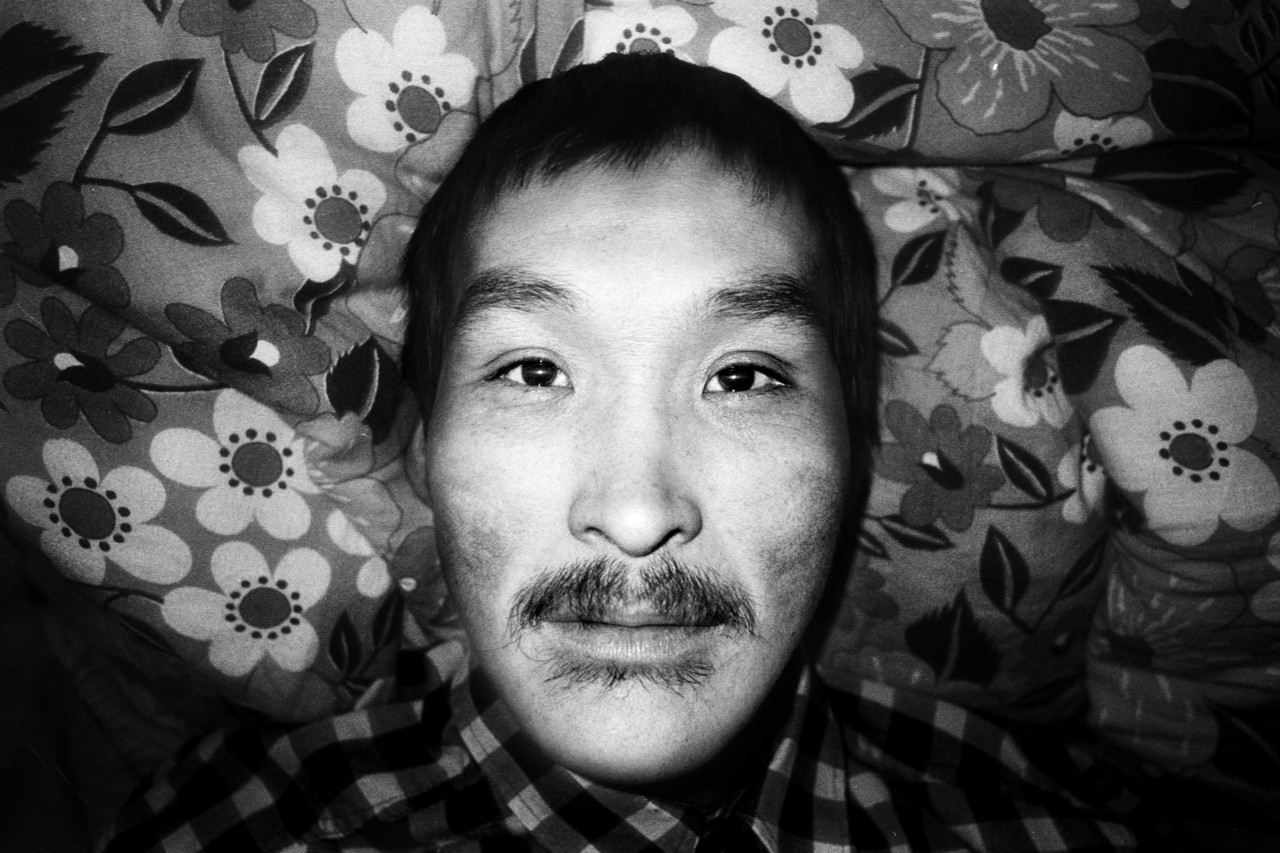

Bangkok was a different situation from my previous projects (“I, Tokyo,” “the Gomez-Brito Family” in Guatemala, “Sabine”) because, one, I wasn’t based there for more than a few weeks at a time and, two, I had no deep personal connection with anyone when I came. So it did become about forming a bond with people, often in passing, on the spot: on train tracks, in alleyways, on random street corners. In Tokyo it was similar, but I lived there for 18 months.

The people I photographed in Bangkok were people I was genuinely interested in. I think they could feel that as well and that’s why they opened themselves to me. Also, to walk as an outsider down an alleyway by myself with a camera, it was a way of showing my own vulnerability: I’m here and I’d like to meet you. When you put yourself out there, people respond to that. What you put on the table you receive in return. At a point I realized any fear I had about meeting people or asking to photograph them was more something that existed in my head.

You’ve previously said that you could feel the distance between yourself and your subjects in Bangkok, because of your role as photographer, the language barrier and other invisible barriers like class – how did you manage to overcome these barriers in order to achieve a closeness that meant you felt able to take the photo?

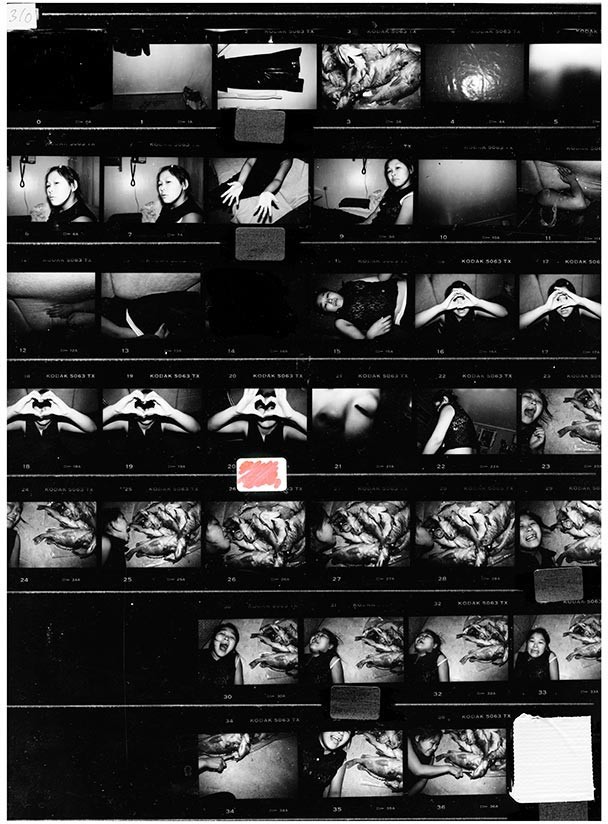

It’s very hard for me to photograph anyone unless I’m physically close to them. It’s very natural for me to want to get up next to them and focus on them and try to feel this sort of emotional connection that’s only possible with that sort of proximity. You’d see this in my contact sheets. It’s rare that I photographed anyone in Bangkok from much more than a meter away. I needed to feel the person’s presence and use that as the starting point.

When taking portraits — particularly as a “stranger” — I’ve always tried to look for what I have in common with that person. To build upon that is another way to achieve an emotional closeness and add layers to the picture. Otherwise, if we only focus on what is different, the pictures can remain superficial or distant — exotic.

When I came back to Denmark from Bangkok I started my project “Home,” where I did many, very intensive, portrait sessions with people inside their apartments. Very intimate moments: young and old couples in love, mothers and their newborn babies. I realized that’s where I could really achieve something closer to who I am and what I think is important in photography.

"For me it’s a way to get to know another person - insisting that we have something to share as humans and that every encounter can be a beautiful moment."

- Jacob Aue Sobol

Other work you’ve produced is deeply personal, such as your relationship with Sabine. Was is easier or harder to create portraits with someone you were so close to, and how did this affect the dynamic of your work?

All of my work descended from “Sabine” because that project embodied where I’ve always derived meaning from photography – when there’s an emotional connection with the person or the kind of heightened sensitivity we feel when we’re in love. I need to feel that warmth in order to connect with the pictures, and that’s what I search for.

I didn’t know how to photograph strangers after Sabine because I often missed this personal connection. What did these people on the street mean to me? I’ve never been satisfied if I try to be the invisible. What’s most interesting to me are the interactions and relationships. That’s the core.

In Tokyo and Bangkok I gradually learned to develop these spontaneous connections on the street. Then, starting with “Home” and going through my work in Siberia (“Road of Bones”) and America, I’ve really focused on spending time with people. I’ll take hundreds of photos of someone in a single portrait session. This uses a lot of energy, but it adds much more depth. For me it’s a way to get to know another person – insisting that we have something to share as humans and that every encounter can be a beautiful moment.

What, in your view, are the key components to creating a good portrait?

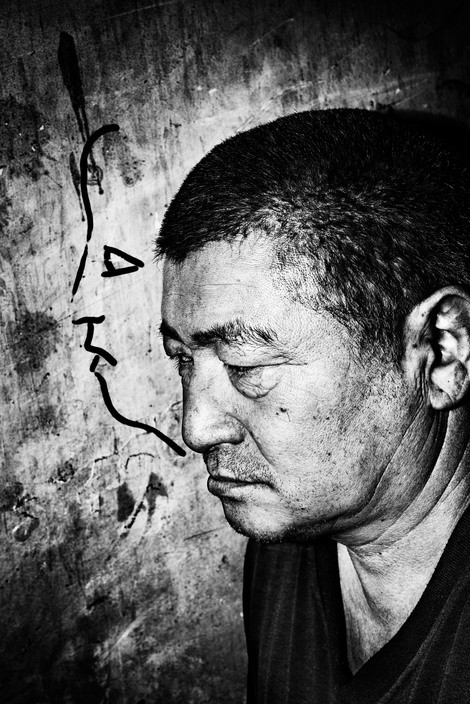

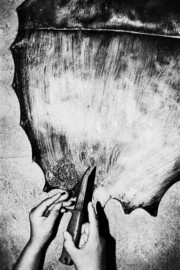

Before anything else I look for the emotional connection. Portraits need to be less about photography and more about the relationship with the person in the frame. That’s when it starts to go beneath the surface. Photograph what you are curious about, fascinated and attracted by, in this person. Is it the soft hair on your lovers neck? Or the wrinkles in an old man’s face? Focus on what it is you want to tell me.

"Photograph what you are curious about, fascinated and attracted by, in this person. Is it the soft hair on your lovers neck? or the wrinkles in an old man’s face?"

- Jacob Aue Sobol

What should a portrait seek to convey about its subject?

Whether in Siberia or Guatemala, I always look for something the subject has which we all have. My pictures come from this fascination with the universality of human emotion and how it shows in individuals.

Conversely, what should a portrait seek to say about the photographer who made it?

I always find myself in the people I photograph. I find the things we share and I build around that. I don’t consciously “seek” anything but rather, I just focus on the person in front of me and remain myself.

What advice would you give an aspiring photographer, looking to improve their portraiture work?

Look for a connection between yourself and the person you want to make a portrait of. Make yourself vulnerable in the process. Communicate. Put yourself at stake. Look the person in the eyes. Insist that this encounter is important to you. Only photograph people you are fascinated by and curious about, and show what you discover. Fall in love – even if it’s just in that moment.

"I’ve retired from taking photographs and am really focused on becoming a fisherman now."

- Jacob Aue Sobol

Earlier this year, you announced that you were retiring from taking photographs. What are you focusing on now?

I am really focused on becoming a fisherman now. I bought my grandfather´s old farmhouse in the south of Denmark — he was also a photographer. I found thousands of negatives in the attic from the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s. He had four daughters and often used them as models in his work. It’s a real treasure for me to find these. I spend most of my days there at sea catching cod, trout, and mackerel. Me and a small crew are building the first combined fishing/photography center in the world: the Brothas Centre for Fishing and Photography. The idea is to combine my two passions in life and make us self-sufficient with farming and fishing. We are renovating the old farm house. Hopefully in a year or so we will be ready to host workshops and have a 100% in-house production place.

Over the past 18 years I took around 400,000 photographs. Many I’ve never seen. So it also feels like a good time to take a breath and go through some of this work from Siberia, America, and Denmark and turn it into books.

The Brothas Centre for Fishing and Photography is also about creating a space where we can explore these ideas of emotional connectedness. We all live very close together and spend a lot of time with each other and it can be a very intense experience. This all feeds back into photography.

The past year has truly been the one with the biggest changes in my life. Only a year ago I was suffering from severe medical depression, and after 6 months when I slowly got out of it I started looking at things in a different way, and I knew that I could not go back to the same way things have been for the last 18 years – looking at life through a camera. Rather I want to take part in life, to be present and to breathe the air without looking for the next picture. I guess it has always been like this, and you feel it in my work – the eagerness to take part in what is going on in front of the camera. I am still recovering from my sickness, but now I have this home, I realized that one of my best friends was the love of my life, and next summer we are going to be parents. Life is truly special.

Jacob Aue Sobol is a judge for the Portrait of Humanity Award, run by 1854 Media, publisher of British Journal of Photography, in partnership with Magnum Photos. The competition is calling for entries of photography that shows seeking to prove that there is more that unites us, than sets us apart. More information about entering the competition can be found here.