Koudelka: Shooting Holy Land

Aaron Schuman reflects on the final cut of the documentary, made over five years, as Josef Koudelka photographed conflicted land and cityscapes in Israel and Palestine

On the 12th December 2019, the documentary, Koudelka: Shooting Holy Land became available on general release. You can learn more about it on the film’s site, here.

Marking this event, Aaron Schuman reflected on the film’s ultimate cut and accompanying video interviews, the allure of Koudelka’s work, and the revelations afforded by seeing the photographer at work on the screen.

“It wasn’t very easy, but it was also not planned”, explains Gilad Baram, director of Koudelka: Shooting Holy Land, in a panel discussion held at Prague’s Kino Světozor in 2018. “This was not meant to be a film. So, the fact that we’re all sitting here today and watching it as a film is a little miracle.”

Baram goes on to explain that, while he was studying photography at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, he was invited to assist the legendary photographer, Josef Koudelka, who along with eleven other prominent contemporary practitioners (including Wendy Ewald, Gilles Peress, Fazal Sheikh, Stephen Shore, Rosalind Solomon, Thomas Struth, Jeff Wall and others) had been invited to Israel and Palestine in 2008 to participate in This Place, an art project initiated by the photographer Frédéric Brenner, which asked each of them to create new work in response to their own individual experience of this complex part of the world. “I suddenly was in a little hotel in Jerusalem,” Baram continues, “shaking hands with the photographer that I’d studied in the first lesson of school, whose work I admired very much, and we went on this adventure.”

Initially, Koudelka was very hesitant to accept Brenner’s invitation, as he felt he had little personal connection to the region. But then, upon encountering the Israeli-built barrier in the West Bank, which separates Israeli and Palestinian territories and communities and is referred to by many as “The Wall” – he discovered underlying memories and emotions resurfacing within himself, and began to draw personal parallels between his own experience of living in Czechoslovakia behind the Iron Curtain more than fifty years ago, and those of the people affected by this relatively new physical barrier today.

Furthermore, as he explains it, “The landscape there is so beautiful, and when I saw the Wall, I felt very sad…in the same way that there is crime against humanity, there can also be crime against the landscape”. Over the course of the following five years, Koudelka returned to the region again and again, and Baram joined him every time, both assisting and filming the photographer as he worked to make what eventually became the book, Wall – Israeli and Palestinian Landscape 2008-2012, published in 2013, by Aperture in the USA, as well as by Éditions Xavier Barral in France, Contrasto Books in Italy, and Prestel in Germany.

"If you photograph people you are losing all the time something; you are running after something which doesn’t exist anymore. If you photograph the landscape, you are waiting"

- Josef Koudelka

As Koudelka notes in a filmed interview conducted by Baram in 2015 in the photographer’s Parisian studio, when many photographers get older their attention often turns from people to the landscape.

Koudelka himself initially came to prominence through his remarkable photographs of the Soviet invasion of Prague, and the mass uprising and violent, city-wide turmoil that followed, in the summer if 1968. This work was originally published anonymously, credited as being by, “P.P. [Prague Photographer]” in The Sunday Times Magazine the following year. Koudelka only acknowledged authorship of the images in 1984, once the threat of reprisals against his family ended with the death of his father. His next major body of work was his intensive exploration of various Roma communities throughout Europe during the late 1960s and early ‘70s – which was first published as Gypsies in 1975 by Robert Delpire and Aperture.

Yet in the mid-1980s, he began to experiment with a wide-angle panoramic camera – the Fuji G617, which produces negatives measuring 6cm x 17cm – and has been applying this elongated frame more specifically to the landscape ever since. “There is [an] enormous difference in photographing landscape and people,” he observes in the same 2015 interview, “If you photograph people you are losing all the time something; you are running after something which doesn’t exist anymore. If you photograph the landscape, you are waiting.”

"Despite the surroundings, there is an overwhelming sense of serenity throughout the film, as the experienced photographer goes about his business of precise observation and considered contemplation"

- Aaron Schuman

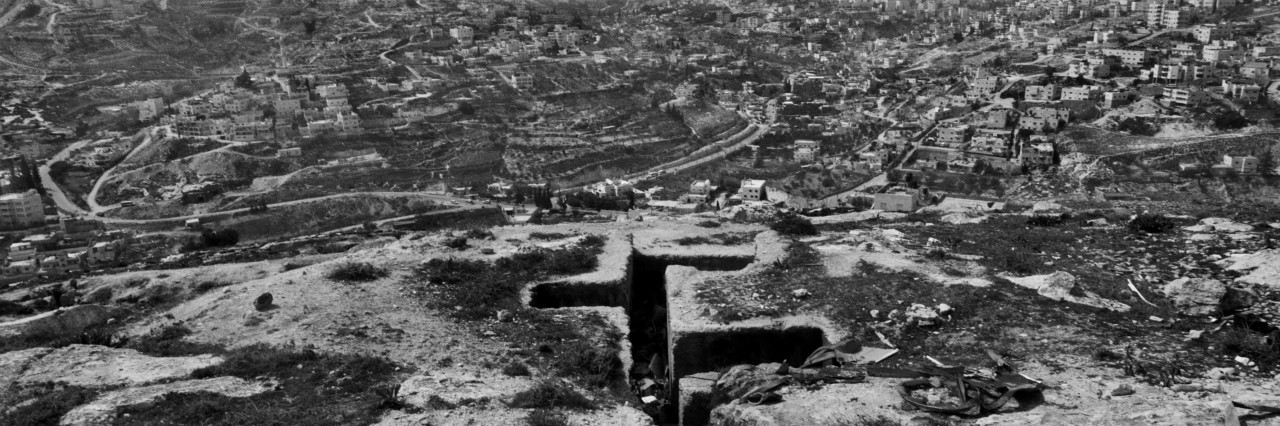

Baram’s film in itself is an exquisite mediation on waiting, which both filmmaker and viewer experience vicariously as Koudelka calmly and repeatedly wanders into and around Baram’s frame with his cameras at the ready – carefully shuffling two steps to the left, then two to the right; hunching over or crouching down on one knee; climbing over rubble to get to higher ground; or even lying on his side and slowly dragging himself through the dust, deep into a long tangle of barbed wire – all in search of the best light or the perfect angle. Of course, the setting of these scenes as well as the subject matter of Koudelka’s work here – the embattled landscapes, contested territories, heavily-fortified checkpoints, and ever-changing borderlands of Israel and Palestine – are highly charged; historically, religiously, politically, visually and otherwise. Yet despite the surroundings, there is an overwhelming sense of serenity throughout the film, as the experienced photographer goes about his business of precise observation and considered contemplation, accompanied by a steady soundtrack of his own footsteps alongside distant dogs barking, chickens clucking, birds chirping, children playing, donkeys braying, rain falling, wind blowing, traffic flowing, helicopters hovering, military-radios chattering, razor-wire jingling, and the occasional yet all important click of the photographer’s shutter.

Furthermore, amongst these beautifully sparse, simple and straightforward day-to-day vignettes of a photographer at work, Baram punctuates the film with Koudelka’s resulting photographs – richly-detailed, wide-angle, black-and-white panoramas that sweep across one’s entire field of vision, incorporating and weighing the central and peripheral information equally, and thus making it impossible to see, absorb, or understand all of the information they contain at first glance. More importantly, Baram holds these monumental photographs on screen – in their full-frame entirely, and in complete silence (no “Ken Burns effect” or stirring music needed here) – for up to thirty seconds at a time, both prioritizing and strongly emphasizing the staggering complexity, emotive significance, testimonial importance and transformative power of Koudelka’s images, as well as that of the photographic medium at large.

"You get up in the morning, get out, and go to look"

- Josef Koudelka

One of the most understated yet poignant and telling scenes in the final cut of Koudelka: Shooting Holy Land opens with the photographer wandering around a hillside farmyard, Israeli settlements hover on the opposite hilltop horizon. A group of young Palestinian boys, intrigued by what this curious old man is up to, start to follow him, at first from afar, and then up close, eventually surrounding him when he sits on a large rock to rest. For the most part, Koudelka ignores their presence, but then suddenly turns to one of the boys. “Want to have a look?”, he says, pointing to the viewfinder of his camera. “No”, the boy replies. “Come”, Koudelka insists, “have a look.” Another boy approaches, braver than the others, and grabs hold of the camera, peering through it towards the distant hill for several seconds. He smiles; then gives back the camera and nods – “Yes!”, he exclaims, and finally several of his friends follow suit.

“That’s what photography is,” Koudelka explains in another scene (one which was originally edited out of the film, but is now available as part of the bonus material that’s included in this soon-to-be-released deluxe edition). “You get up in the morning, get out, and go to look.” He then looks out of frame at Baram, directly in the eye, and meaningfully holds his gaze: “And if you find something interesting to photograph…you think: ‘Something might stay.’”