Ascent to Heaven

Lúa Ribeira talks to Diane Smyth about the five projects that make up Subida al Cielo, her new book and first major solo show, and how they all draw on her questioning of power, honed by her upbringing in Galicia.

Lúa Ribeira grew up in Galicia, a region to the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula that has the status of a historic nationality due to its distinctive language and traditions — the expression of which were forbidden in the years of violent suppression and neglect during the dictatorship of General Franco.

This history has profoundly affected Galicia and its people, and that includes Ribeira, who says her exposure to “the dynamics of oppression” has permanently shaped her worldview.

“It’s a history that hasn’t been resolved,” she says, pointing to the thousands executed, jailed or exiled during the Spanish Civil War and the decades that followed. Moreover, there was no recognition of these crimes following the so-called ‘Pact of Forgetting’ that was made during Spain’s transition to democracy in the late 1970s.

“Even during my school years [in the 1990s], we were not clearly taught that our language had been forbidden, and so had any expression of our culture,” she says. The consequence was confusion about their collective identity, she says. Growing up, “there was this sense of shame — about the accent, the place you came from. There was the fact that your parents grew up in this context of repression. It’s very engrained.

“And that inevitably means that I am always looking through that lens — looking at how power works and how it affects certain people and communities.”

"If you don’t give yourself, why should anyone just give themselves to you?"

-

Ribeira is now based in Bristol in the UK, settling there after studying in Newport just across the Severn Estuary, completing the influential documentary photography course set up by Magnum colleague David Hurn half a century ago. Yet her connection to her upbringing in Galicia, and to Spain, continues, both through the projects she shoots there, and through this ongoing examination of power in her work.

She is currently making a project collaborating with people involved in the drill and trap music scenes in Spain, for example, which she sees as counterculture movements. Her breakthrough series, Noises (2015–19), begun while at Newport, was made with British-Jamaican women into the dancehall scene.

Ribeira immerses herself in the communities with which she works and sees her images in terms of collaborations, sometimes theatricalizing, proposing actions, and sometimes shooting straight documentary. “I like to think that we can use photography to talk about the imagination,” she says. “Things that are real but not that tangible.”

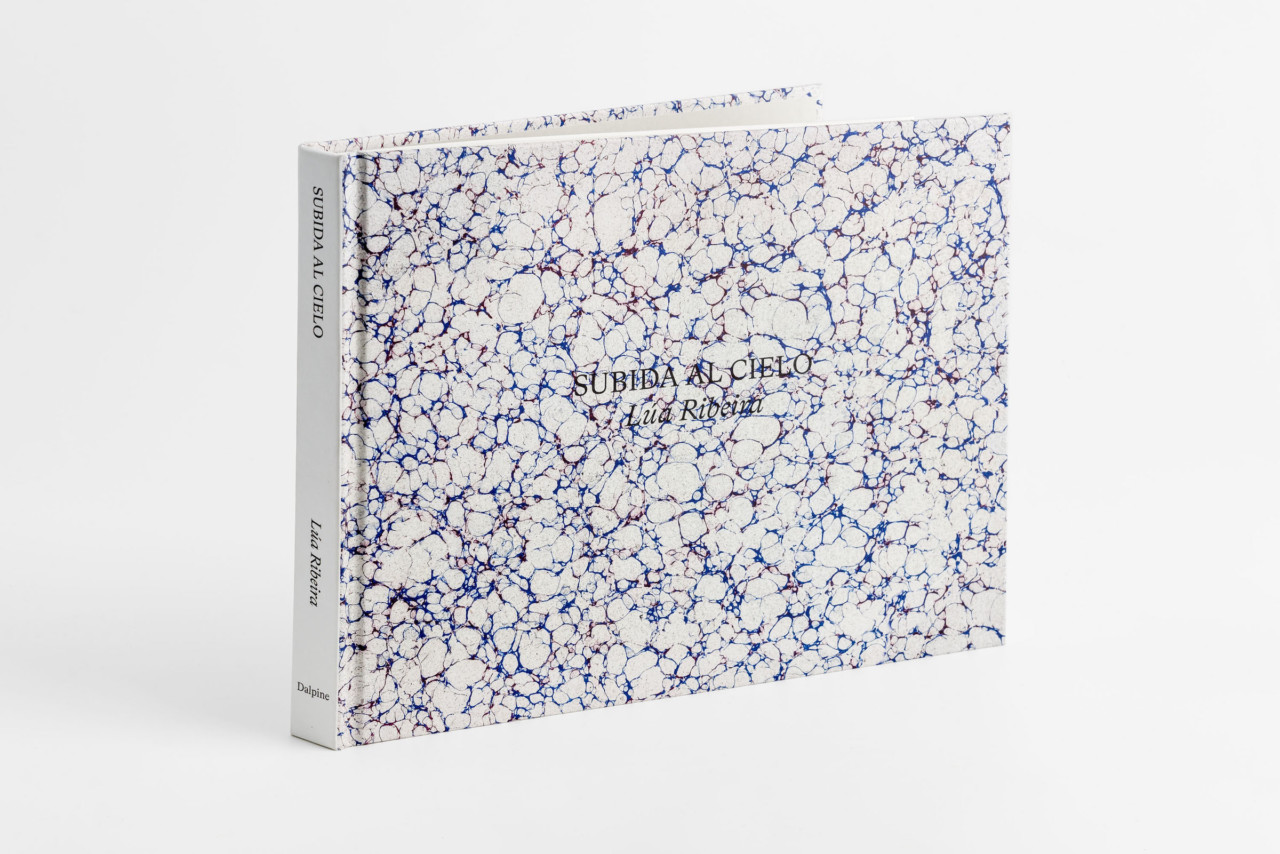

Her new book, Subida al Cielo (‘Ascent to Heaven’), published by Sonia Berger of Dalpine, who has also curated her first major exhibition, showing at Kutxa Kultur Artegunea in San Sebastian (March 16 until July 02), gathers together five series made over the last decade in locations as diverse as a park in England, Tijuana in Mexico, and the border of a Spanish enclave in Morocco.

"It’s a political decision to trust people."

-

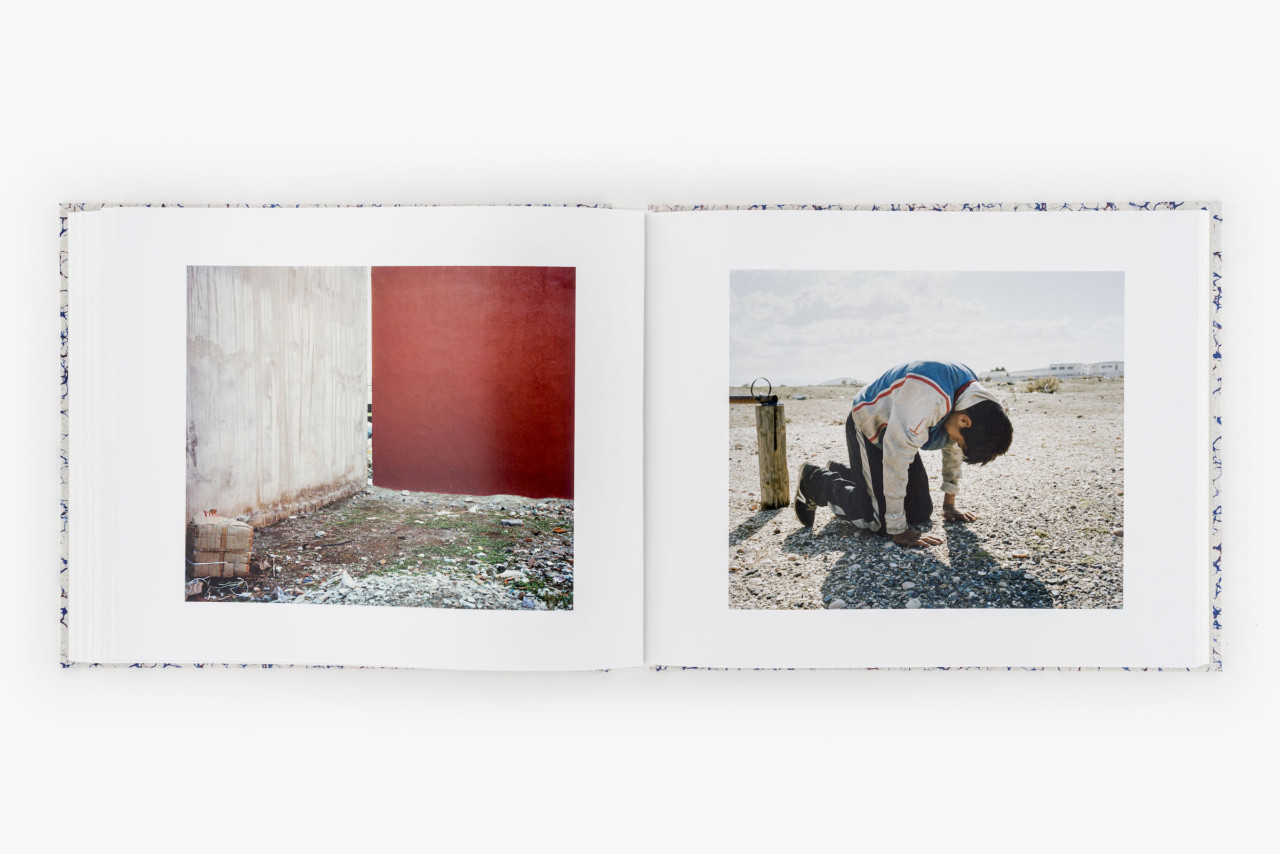

The common thread is her interest in people and communities that have been marginalized, and her refusal to frame them this way. In North Africa, on the border of Morocco and the Spanish enclave of Melilla, she worked with young men trying to migrate into Europe, hanging out and building images that emphasize their intelligence, camaraderie, and resilience, not the usual depictions of victims or threatening behavior often favored by the Spanish press.

She named this series Los Afortunados (‘The Fortunate Ones’), working on it in the two years before the Covid pandemic, but she’s still in touch with some of those she photographed — in particular, Ayoub El Ghaouzi, without whom she says she couldn’t have made this work. I ask if she ever felt worried, a young woman befriending a group of men trying to stowaway to Spain. “It’s a political decision to trust people,” she replies.

“For me it’s important to know our fear, and that’s something I take responsibility for — to not be fearful or suspicious. That’s the narrative the mainstream produces. The minimum, of course, is that we have the common sense to get out of dangerous situations if they come into play. But if you don’t give yourself, why should anyone just give themselves [to you]? What connection will there be if there’s no exchange of vulnerabilities?”

Another series, made in 2019 in a semi-abandoned park in Tijuana, Mexico, set against the border wall with the US, raises similar issues. It shows a group of men and the precariousness of their lives on the edge of this notoriously violent city.

She first went there on a group project with Magnum, designed “to go beyond the conventions of an often melodramatic news cycle and the relentless political posturing that has defined public understanding of the Mexico-USA border.” Ribeira was initially unsure how to pitch up in an unfamiliar place and make a body of work over a short period of time. She decided to narrow her focus after meeting Jose and Pirana in a 24-hour convenience store near where she was staying, close to the park where they lived, known locally as ‘la Jungla.’

Concentrating on the park and the relationship between the pair gave her a small frame to work in. “Day by day we became closer to each other and I became interested in the relationship they had with La Jungla’s land: the enigmatic, mythological quality that arose through their language, perhaps as a way of survival,” she writes in Subida al Cielo. “Deportation, border-crossings, trafficking, addiction and murder became the daily background noise for well-formed stories with more dignified purposes.”

"When you transgress the expected barriers, a profound connection can build."

-

Ribeira tells me that the first time she went there, it was only for 10 days, “but I built really strong relationships.” She says there was something special in what developed, and that was immediately apparent when she returned.

“I think sometimes when you transgress the expected barriers, a profound connection can build. If you want it, there’s trust. Because I reached out to someone who you might not usually, and they welcomed me, there was something very unusual, something that might be transformative for how we live our everyday lives.”

Ribeira’s images from La Jungla are close-up and mostly focused on people. She gives little sense of their wider situation — and deliberately so. With her images she hopes to downplay the context to produce more archetypal pictures, she says, to reduce the specificities of certain communities to emphasize something more universal. She hopes to talk about the similarities between people, rather than pick out their differences.

"Myths to shape our lives. They are equally real."

-

This is one of the reasons she combined five separate series into one exhibition and book, and this thinking also underpins her series shot in Bristol from 2017–18.

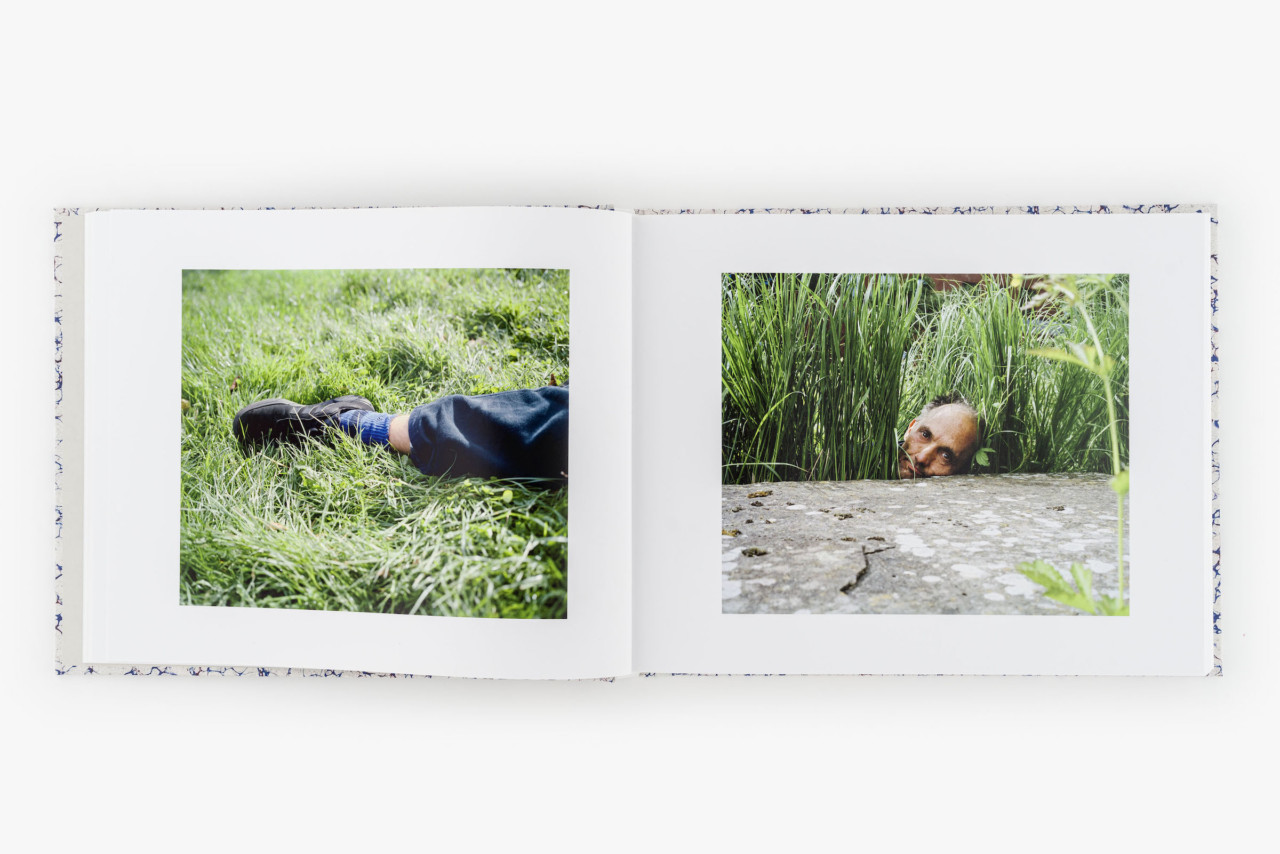

Commissioned through the Jerwood/Photoworks Award in 2017, this work originally aimed to draw attention to the city’s homeless crisis. However, though Ribeira spent time with people experiencing homelessness, she deliberately opted to work in parks, where the boundaries between communities blur.

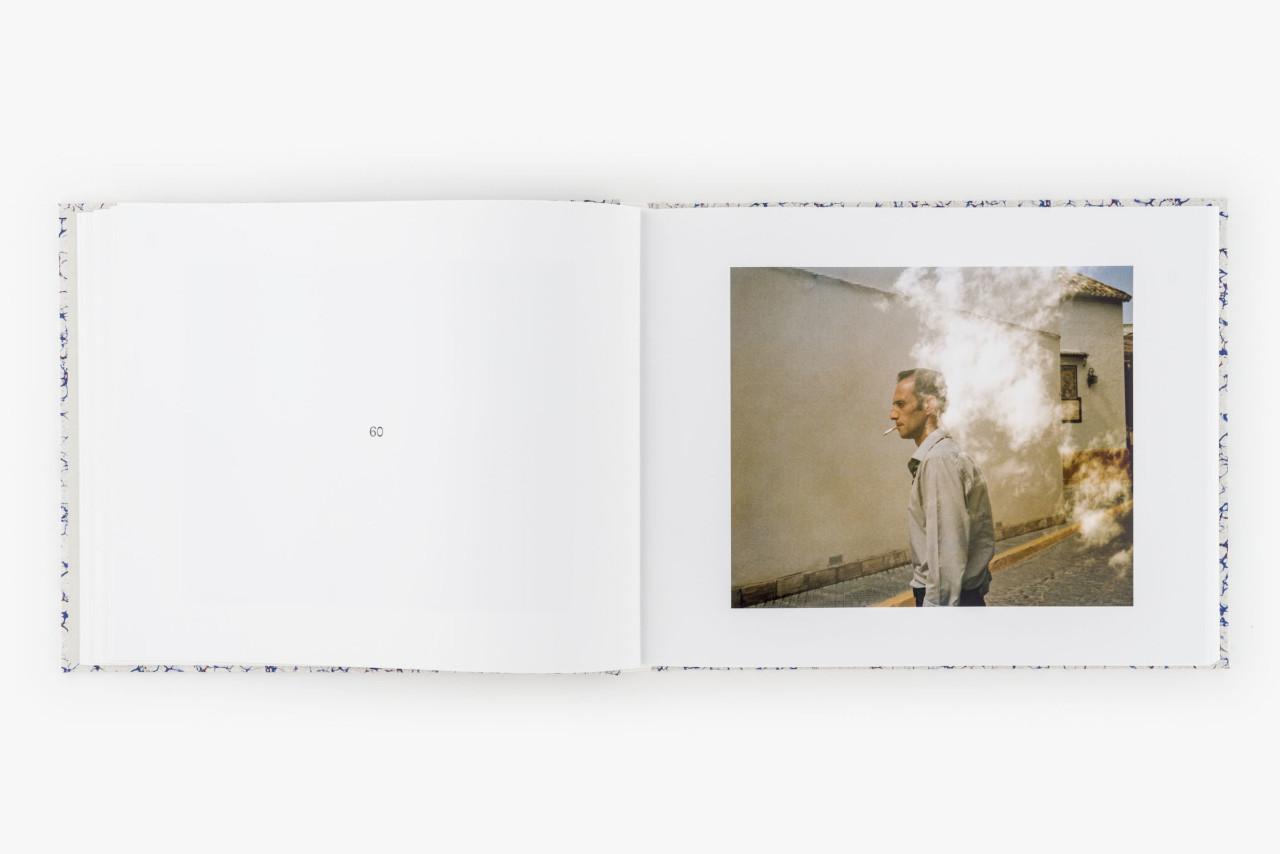

The final series, Subida al Cielo (the same as her new book and exhibition), deliberately mixes images of people in various life situations, including Ribeira’s friends and family, and also includes masks and set up shots, “things more on the level of games or play,” she explains. “You can take a documentary image of how we look here, but then there are the myths we use to shape our lives. They are equally real.”

"I want to leave a lot for the viewer. I want you to think what you want."

-

These myths recur in Las Visiones (‘The Visions’), photographed in the industrial town of Puente Genil, an hour south of Cordoba in Andalucia, shot in 2019.

Every Easter, children dress as Biblical characters, wearing costumes and masks. The series, originally commissioned by Magnum to capture Holy Week, hint at the rituals that help people handle the unknown, says Ribeira. And, again, while she shows the town and its outskirts, she deliberately focuses away from the procession itself. She shows the unfamiliar scenes that surround it, but not the reason that they exist.

Aristócratas (‘Aristocrats’), made in her homeland, Galicia, also draws on themes of religion and marginalization, showing a group of women who are deemed to be disabled, and are cared for by Catholic nuns. Ribeira worked on the photographs from 2016 to 2019, but grew up seeing the women, because they spent summers in her grandmother’s town.

She was curious about how they had come to be a confined group, she explains, why they were defined ‘disabled’ and cared for outside mainstream society. “I’d always seen them as a little girl, and in 2014 I started to spend time with them, connecting,” she says. “And it’s very special, you know. I find myself at home there.”

Many of her images show the women doing everyday things, others show them during theater workshops acting out social rituals from which they may be excluded — weddings, perhaps, or funerals. The title is a reference to their separated status, to the way that, like Royals, they are separated from everyone else. But the name ‘Aristócratas’ is also a reference to Diane Arbus, whose images of the mentally disabled — and others — have been critiqued for their ‘othering’ perspective.

Arbus described “freaks” as aristocrats because, in her words: “Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience. Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life.”

"It’s very special. I find myself at home there."

-

Riberia is well aware of the criticisms of Arbus’ work, and how they might be applied to her own. She’s also well aware that she now occupies a privileged position as a member of Magnum Photos. This factor perhaps complicates what happens when she photographs people who are experiencing exclusion, those with less power than her. She’s happy to be asked about it, though she adds that there’s little she can say. “It’s always the question, and there’s no proof I do right or wrong,” she muses.

“I can’t prove or convince anyone of my work ethics, so it’s impossible to answer these points. But I want to believe that [my] images carry something of the truth of the processes, of what’s been happening behind the scenes. Of course, my position is changing, and I have a little bit of resistance [inside] to accept that more established position. That’s a question for me, how I will roll with that in the future.”

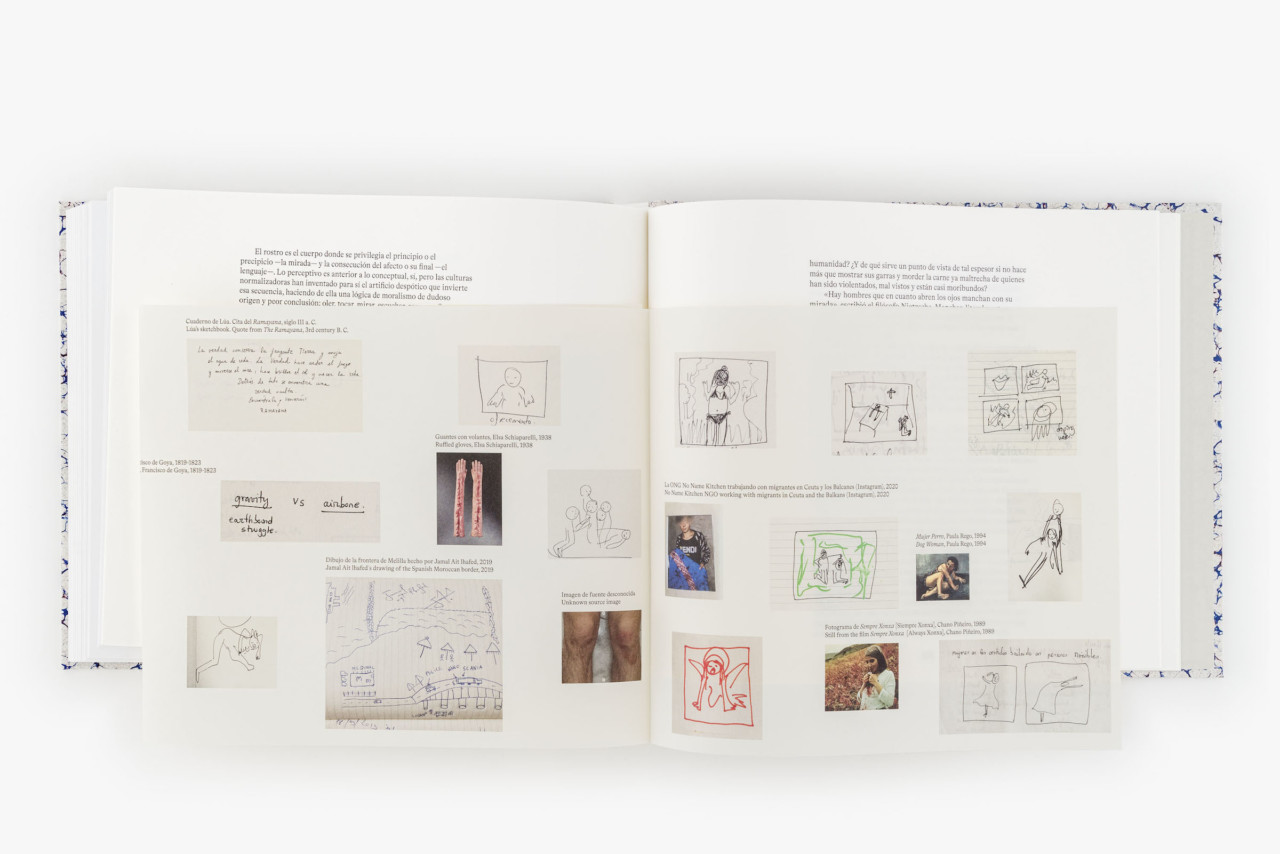

And while Ribeira explains a little of the context in which she makes her work, and in which her subjects are living, she emphasizes the ambiguity of images, their ability to evade and transcend words. She’s a keen collector of images and has included some in her show in San Sebastian, references to paintings by Paula Rego and Goya, for example, or her own sketches.

She’s attracted to Baroque paintings and Catholic icons because of their depictions of suffering, she says; their sense of the universal nature of the human condition, and aspects of life beyond comprehension. And she feels images “relate to each other in unpredictable ways”, she says, easily slipping from our grasp.

“We try to impose a very tight idea of what images communicate, but I feel images are not that controllable,” she says. “I work quite instinctively, and if I try to rationalize too much afterward, that’s just a construction. And, actually, I don’t want to control. I feel more comfortable with ambiguity, and the idea that my images hold that ambiguity. I want to leave a lot for the viewer. I want you to think what you want.”

Subida Aa Cielo, published by Dalpine, is available via the Magnum shop.

The exhibition runs at Kutxa Kultur Artegunea in San Sebastian March 16 to July 02.