On Protest Photography

Maisie Skidmore explores the power of photography to change the status quo

Magnum Photographers

In hindsight, the resistance movement that rose up in the mid-1960s against the U.S. government’s decision to intervene in the Vietnam War is one of the greatest of the past 100 years; a magnificent coming-together of draft resisters, hippies, conscientious objectors, black and white, rich and poor, all united in their objection to the government’s actions. But was any thought given to how future generations would view such togetherness further down the line? Or was it simply a string of spontaneous and impulsive actions that drove many protesters to get involved?

That was the case for Jan Rose Kasmir, a 17-year-old foster child from suburbs of Maryland who found herself one of the estimated 100,000 demonstrators who took part in the March on the Pentagon on October 21st, 1967 in resistance against the war. Unbeknownst to her at the time, Magnum photographer Marc Riboud had his lens keenly fixed on her as she stood nose-to-bayonet with one of 250,000 solders employed to crush the protests by any means necessary. And so it happened that, as Kasmir offered a white flower to an armed solder in front of her, Riboud captured her profile, earnest and open, and in a instant created one of the most iconic images of the movement.

“She was just talking, trying to catch the eye of the soldiers, maybe try to have a dialogue with them,” Riboud told an interviewer some 40 years after the photograph was taken. “I had the feeling the soldiers were more afraid of her than she was of the bayonets.” Kasmir, in another interview, concurred. “I was begging them to come join us,” she said. “At that moment, the whole rhetoric melted away. These were just young men. They could have been my date. They could have been my brother. And they were also victims of this whole thing. They weren’t the war machine. They were human beings and they were just as much a puppet of this whole horrible, horrible travesty.” In one shot, Riboud distilled the human connection between Kasmir and her adversary into an indelible symbol.

This symbol has recurred time and time again in clashes ever since. Take Jonathan Bachman’s poignant photograph of a woman in a long flowing dress standing in front of three rapidly approaching policemen, taken just last week in Baton Rouge at one of many Black Lives Matter protests happening concurrently around the world, for example. The reference back to Riboud’s Girl With a Flower is clear, but where Riboud’s original was repeatedly reprinted, Bachman’s went viral within the day. Every outlet that runs it is calling out for information as to who the woman in the photograph might be.

"Photography cannot change the world but it can show the world, especially when it changes"

- Marc Riboud

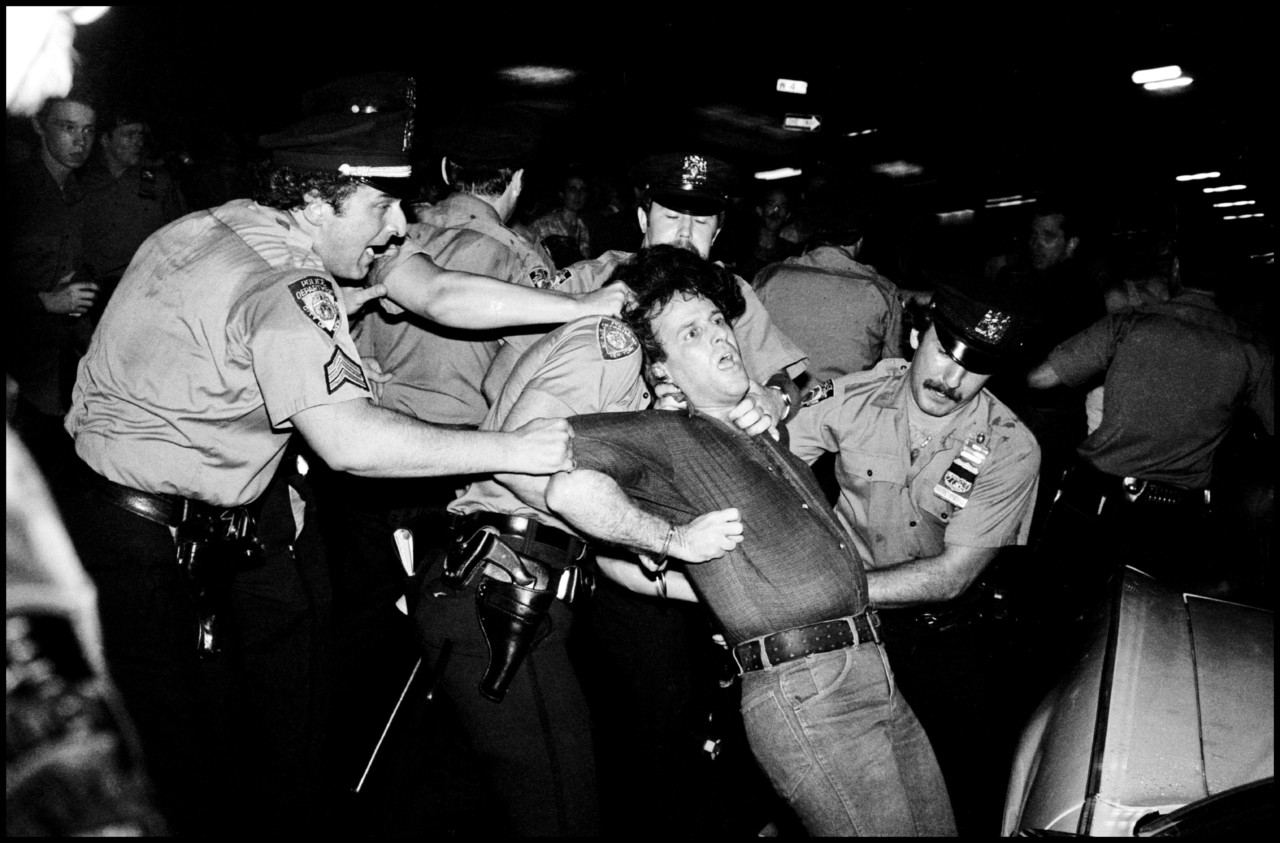

This, of course, is the great power of photo-journalism; it serves first and foremost as a tool to create empathy in its viewer. Where the reported actions of a group, however well-intentioned, can quickly spiral into discord in newspaper reports, a photograph of one person reminds onlookers of their own compassion and clemency. What’s more, when it comes to protests, photographs printed in magazines and newspapers are fundamental to their political success – without some record or physical proof for the archive, mass uprisings can be quieted and the movement they represent remain impotent. The publication of Riboud’s Girl With a Flower played a small but immutable role in transforming public opinion of the Vietnam War to such an extent that, by the time the war ended, many government officials had publicly denounced it. “Photography cannot change the world,” Riboud once said, “but it can show the world, especially when it changes.”

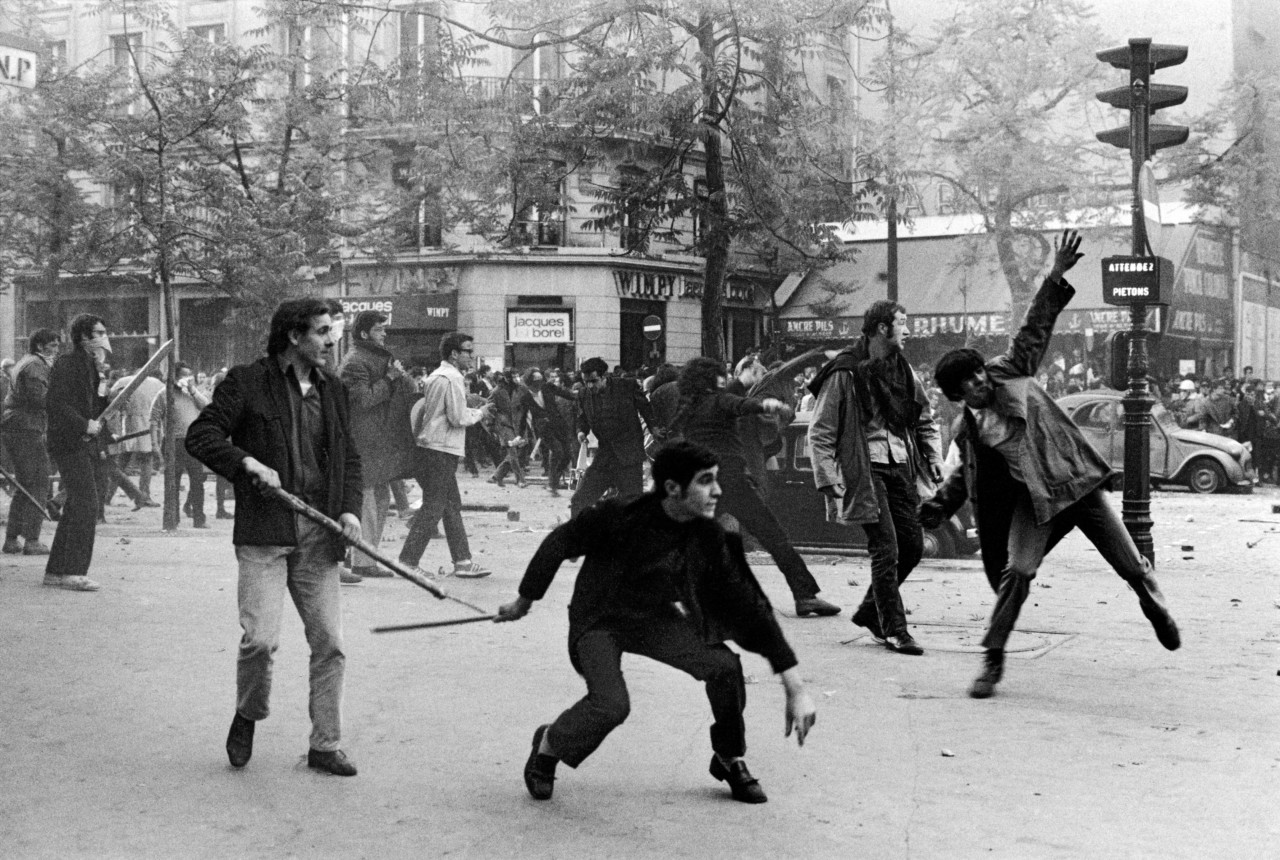

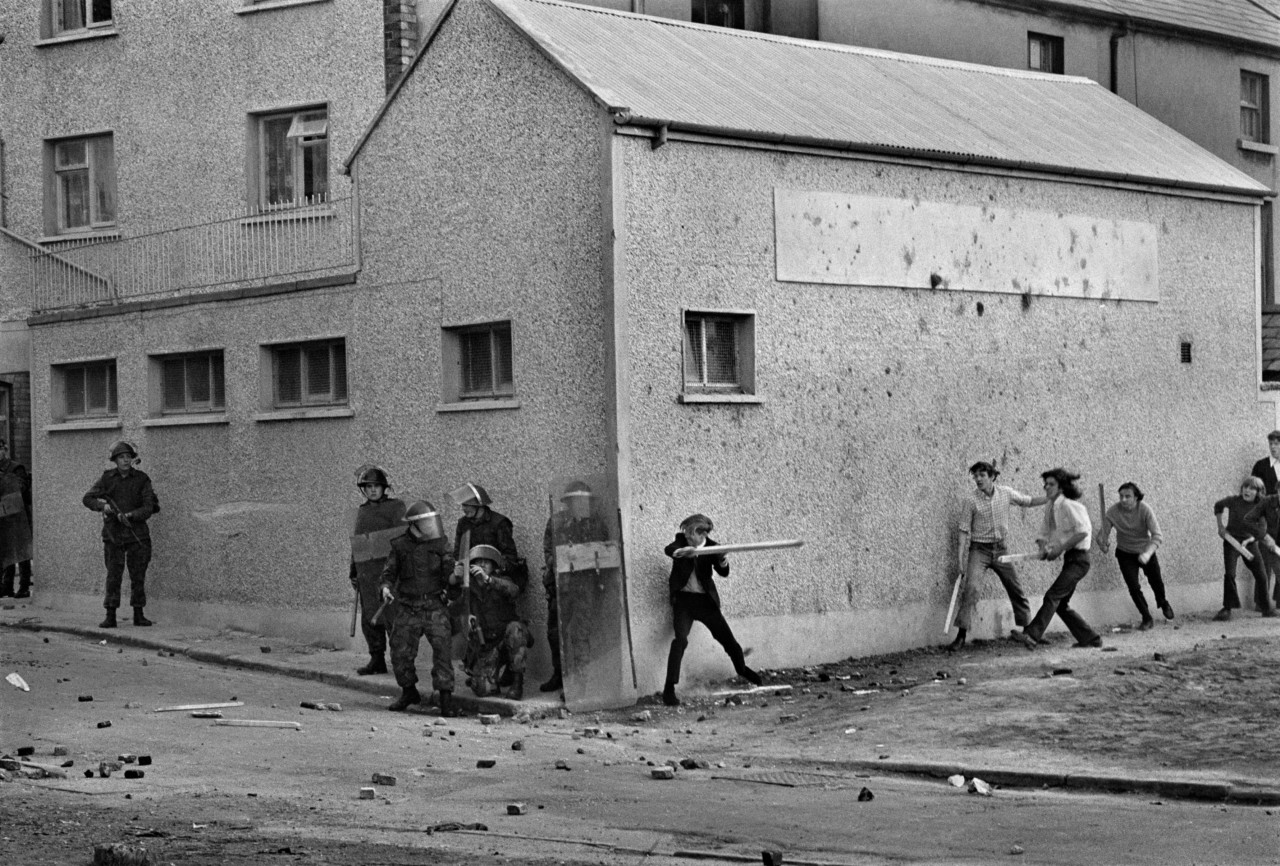

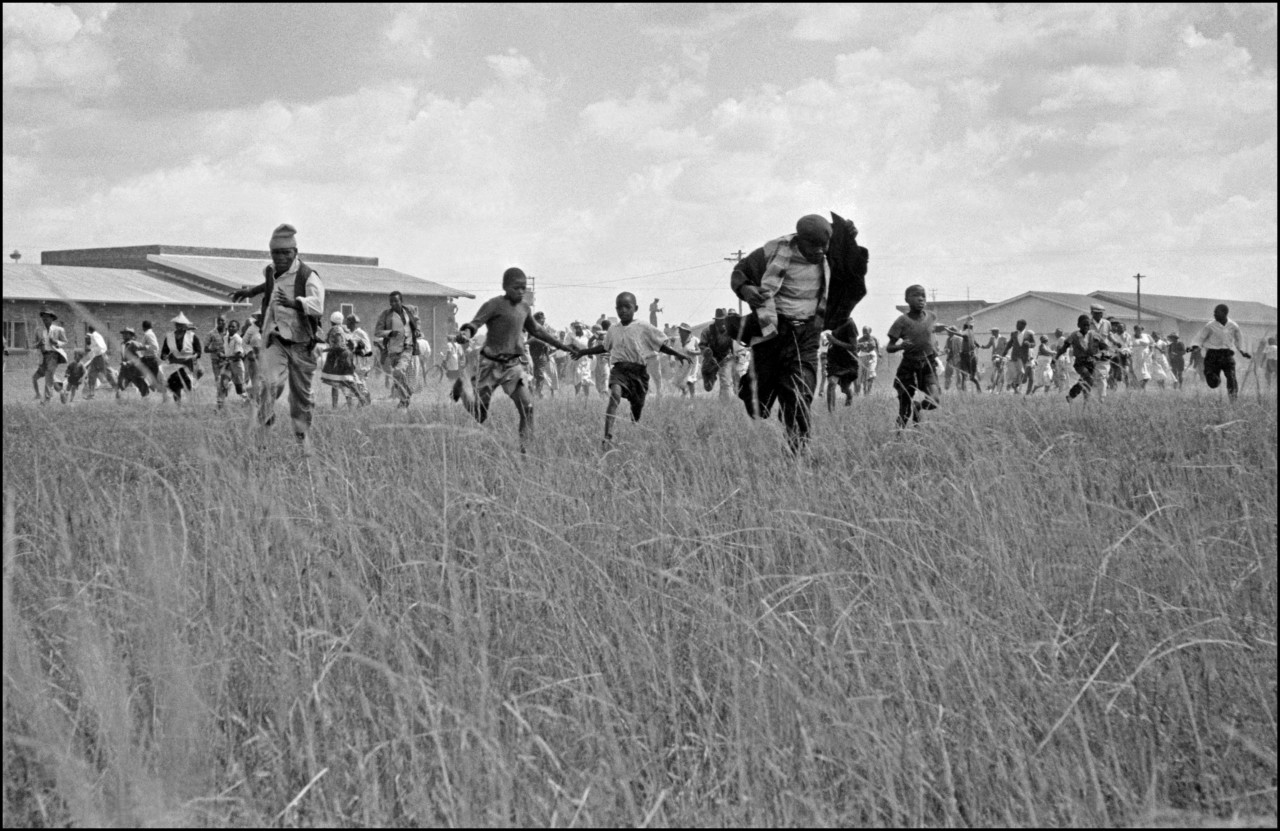

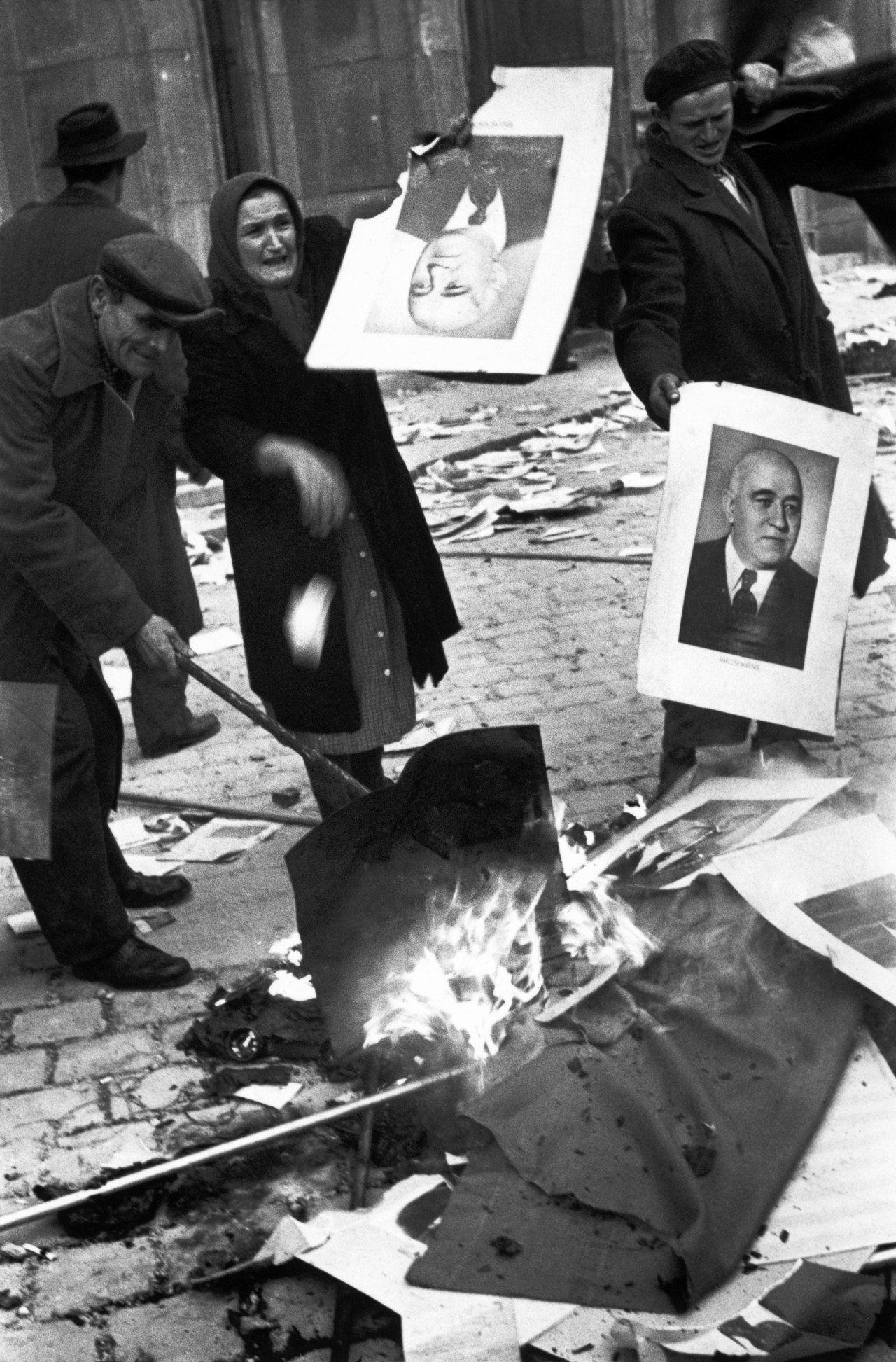

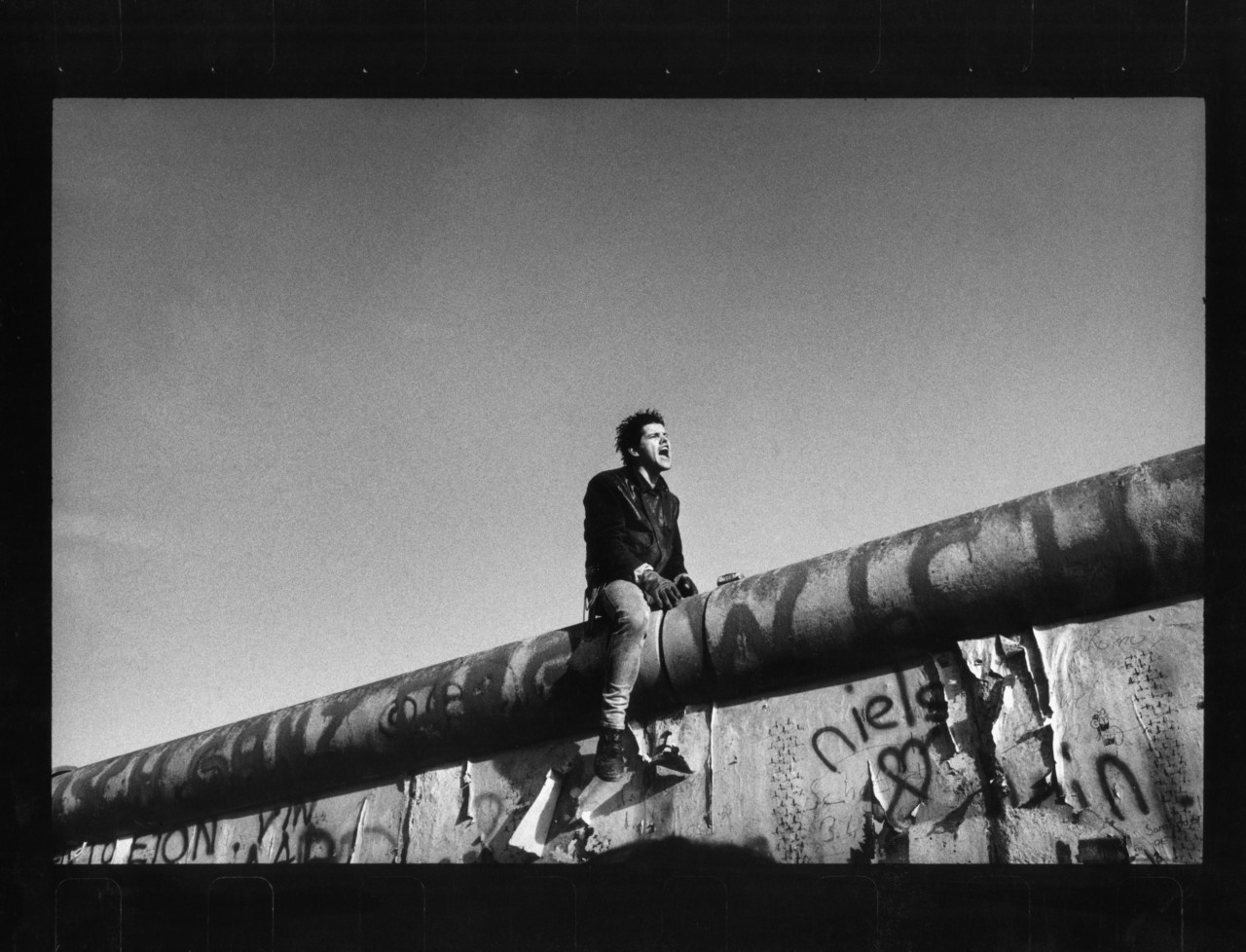

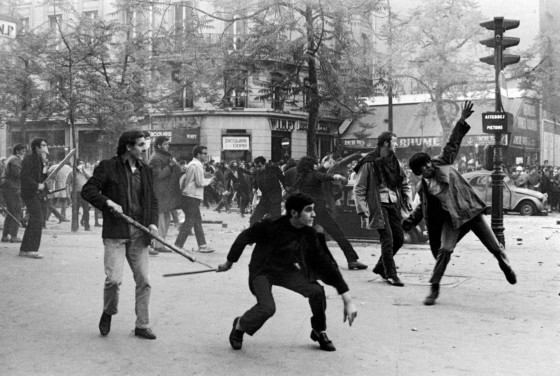

The anti-Vietnam War effort was far from the first of its kind. Ever since Magnum’s foundation in 1947, its photographers have sought out social resistance and fights for freedom of expression in the furthest corners of the world. The resulting photographs, from Josef Koudelka’s harrowing images of the Warsaw Pact troops’ invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, to Bruce Davidson’s documentation of the Civil Rights movement and Bruno Barbey’s images of the Parisian student revolts of May 1968, are among the most powerful in the history of photojournalism. They represent the coming-together of ordinary people as one to stand up against the status quo.

Stuart Franklin’s 1989 photograph of a single man standing in front of a row of five T59 tanks in the middle of a deserted street in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square has become iconic. The image was taken during ongoing Chinese demonstrations calling for freedom of speech and an end to corruption. When he took the image, poised on a hotel balcony, Franklin thought it to be unremarkable. It wasn’t until the days which followed, while his film was making its way back to Magnum headquarters in France, that he realized how little reportage of the protests and ensuing crackdown had made it out through the media at all: with the oppressive measures taken by Chinese media, his poignant snapshot of the so-called ‘Tank Man’ was to become a monument to the freedom of expression. Franklin’s own aim, however, was far more modest. “As a photographer, the objective is to crystallize the emotion of an event and communicate that as effectively as possible,” he told The Guardian some years later. “My pictures follow the different efforts I made to come to terms with the events as they were unfolding, to tell the story even as it was changing.”

Raymond Depardon muses on the power of protest. To his mind, a photograph is only equal to its creator’s understanding of its potential impact. “I’m coming from journalism,” he once said, “but at the same time I’m tempted by poetry, politics, and maybe the idea of being a witness, a belief that you can still change things with the image.”