Making the Image: Leonard Freed’s Work on the NYPD

The photographer explains how a determination to understand policemen and their day-to-day life informed his work

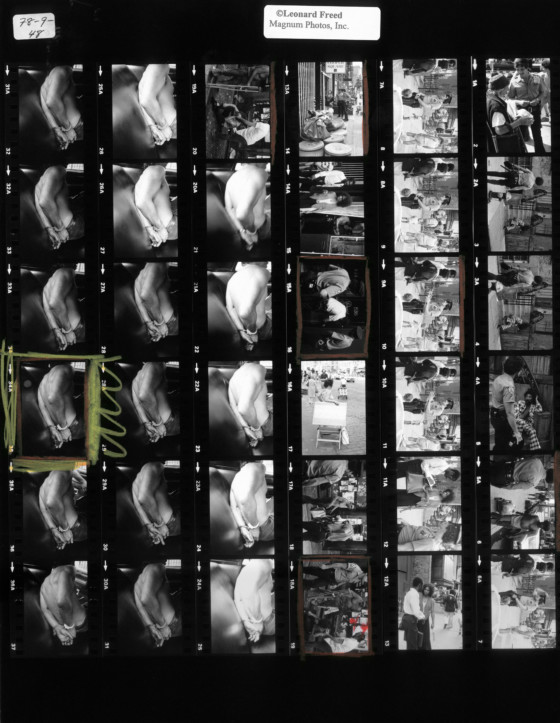

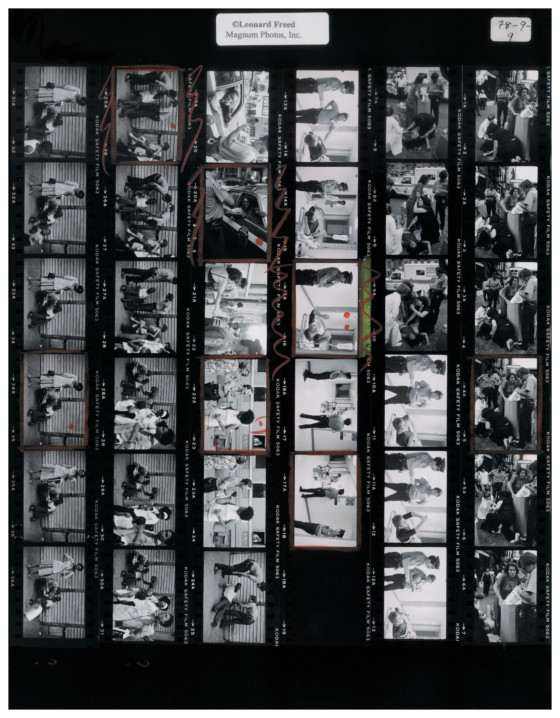

Contact sheets: direct prints of sequences of negatives were – in the pre-digital era – key for photographers to be able to see what they had captured on their rolls of film. They formed a central part of editing and indexing practices, and in themselves became revealing of photographers’ approaches: the subtle refinements of the frame, lighting and subject from photograph to photograph, tracing the image-maker’s progress toward the final composition that they ultimately saw as their best. There is a voyeuristic aspect to looking at a contact sheet also: one can retrace the photographer’s movements through time and space, tracking their eye’s smallest twitches from left to right as their attention is drawn. It is as if one were inside their head, offered a privileged view through their very eyes from the front row of their brain.

As Kristen Lubben wrote in her introduction to the book, Magnum Contact Sheets, first published in 2011 by Thames and Hudson:

“Unique to each photographer’s approach, the contact is a record of how an image was constructed. Was it a set-up, or a serendipitous encounter? Did the photographer notice a scene with potential and diligently work it through to arrive at a successful image, or was the fabled ‘decisive moment’ at play? The contact sheet, now rendered obsolete by digital photography, embodies much of the appeal of photography itself: the sense of time unfolding, a durable trace of movement through space, an apparent authentication of photography’s claims to transparent representation of reality.”

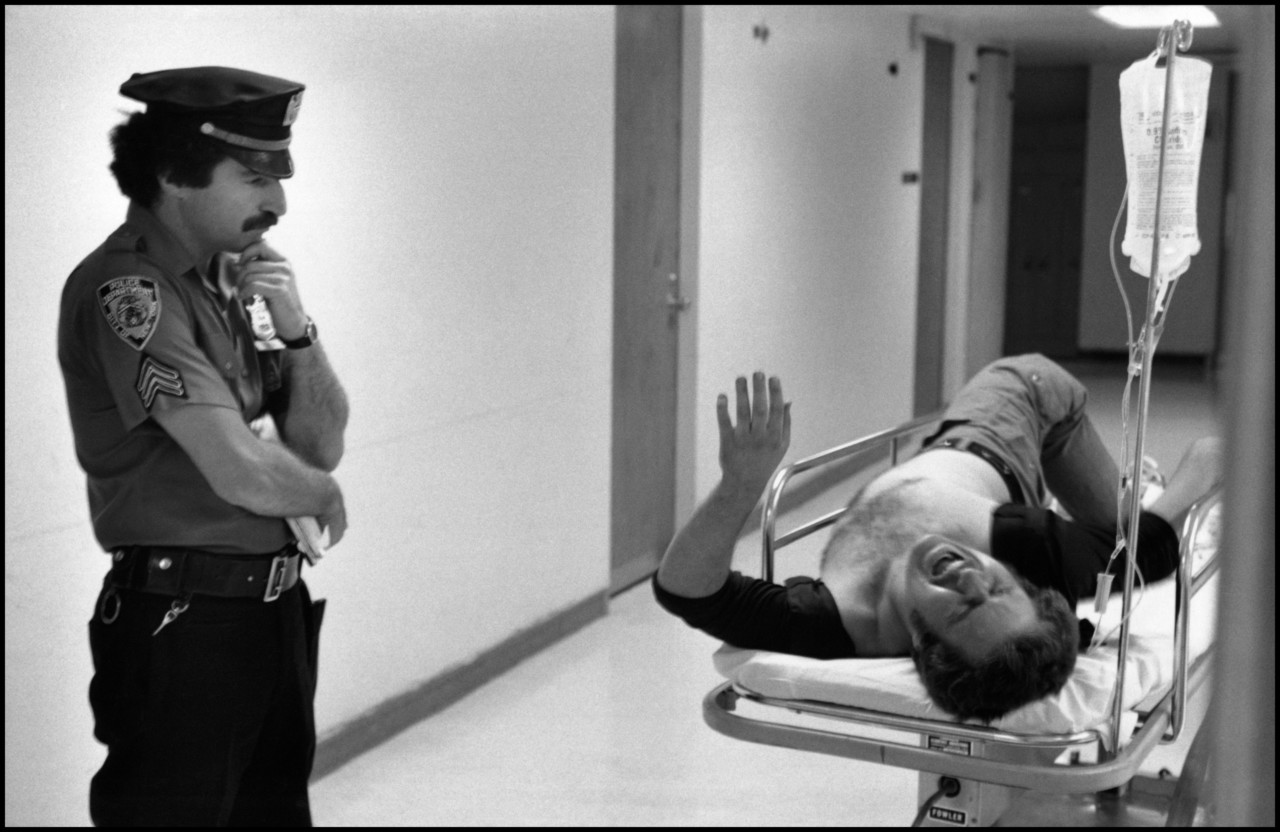

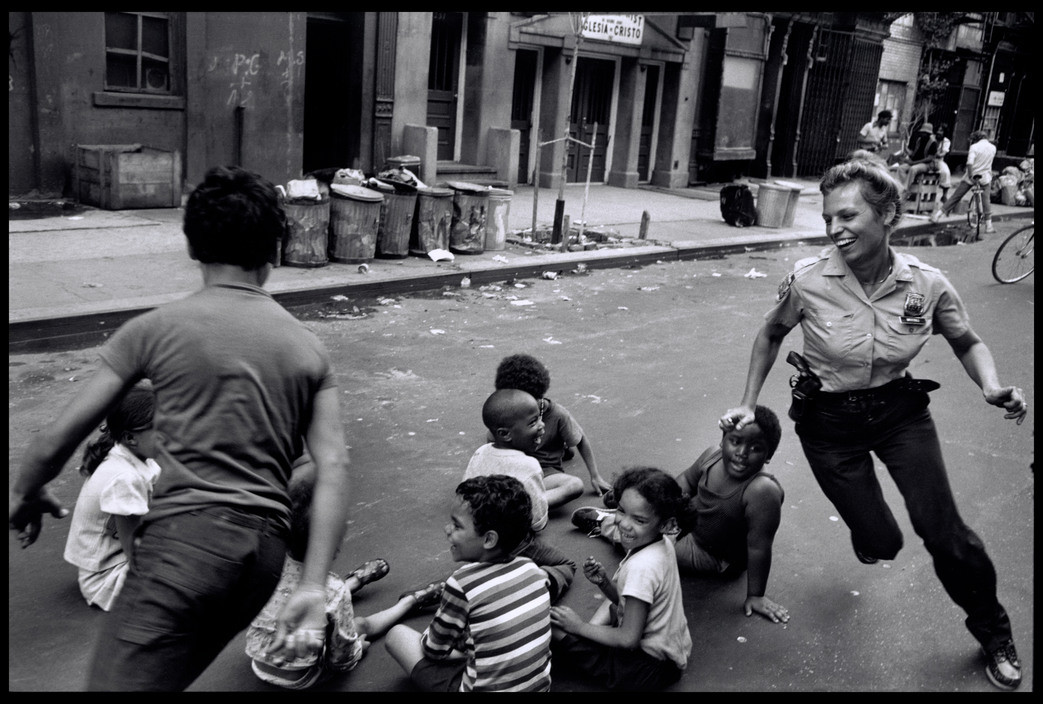

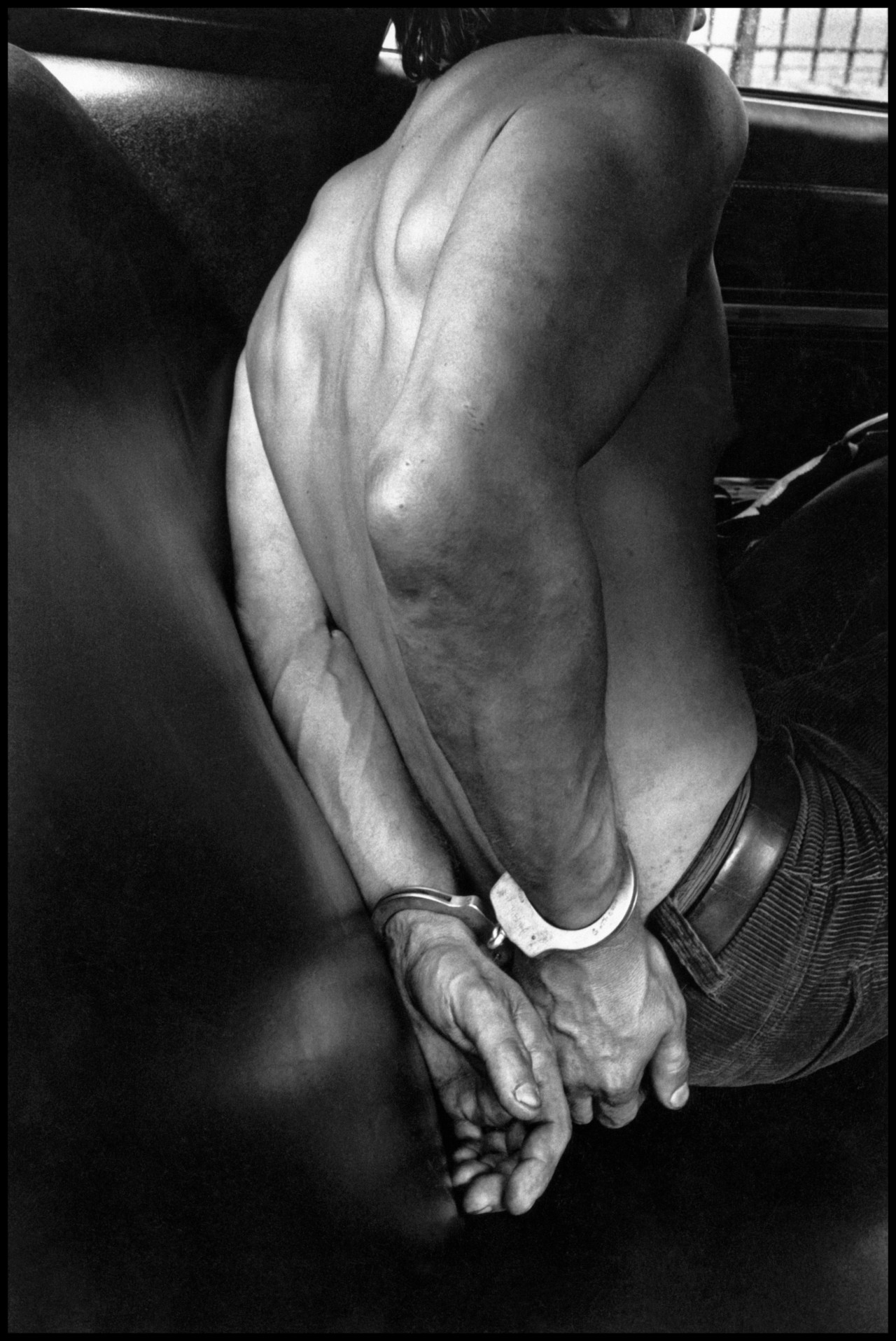

Here we look at the making of Leonard Freed’s portrayal of New York City’s Police Department during the famously tumultuous 1970s. Freed’s contact sheets capture the close relationship which he built with policemen and his determination to understand their work and lives. The images offer an alternative view of the daily life of working-class people, both those in and out of uniform.

Two of Freed’s contact sheets from his work on the NYPD are available as part of the New York Collection on the Magnum Shop. Freed’s image of an NYPD officer playing with kids in a city street is also available as part of the New York Fine Print collection.

You can read other entries in Magnum’s series on contact sheets, and the making of iconic images here.

New York, USA, 1978

“The London Sunday Times asked me to do a story on violence. I photographed what I thought violence meant to me. If I couldn’t open a window because of pollution, that was violence to the person, I thought. And graffiti was a violence to the eyes, and a lack of trees in the city was a violence to the mind. Anyway, that was the story I sent to London. Afterwards they sent me a telegram from London, saying ‘Great, loved the story, but needed more blood and gore.’ I then went out and photographed over fifty homicides. They just loved it.

I was more interested in who the police were. I wanted to understand what they do, why we cannot do without them. It was a sociological study related to what I felt about the police. I assigned myself to do this project.

I wanted to get involved in their lives; to see why some people could call them ‘pigs’. What do people know about brutality? Policemen are working-class people. They’re not psychiatrists, they’re not lawyers, they’re not doctors. They are blue-collar workers. I look at them from the point of view of the working class, not the ruling class. I am very conscious that I come from a working-class family myself. My father was a working man.

I can identify myself with these people. But I am not romantic about working-class people… So this is why I tried to understand the police, to have contact with them, be sympathetic, talk to them, understand their problems. Police don’t talk to other people; they never talk to anyone about their experiences. They are not educated to talk; they are supposed to be strong, silent types. I literally spent days with policemen. Some didn’t want to work with me; some agreed. I didn’t want to be against them, to show brutality. I was not a spy…

Contact sheets are mostly a waste of money, I find. 99.9 per cent of the frames on the contact sheet are mistakes one makes while photographing. Because it is a waste of money, I love them. There are things in life we must do just because we find them unprofitable. Also, contact sheets are private: they belong to me, whereas photographs, once they are out of my hands, take on a life of their own.”