Making the Image: Red Fuji

Chris Steele-Perkins on the flickering red light emanating from nearby roadworks which, in combination with a long exposure, created his ambiguous image

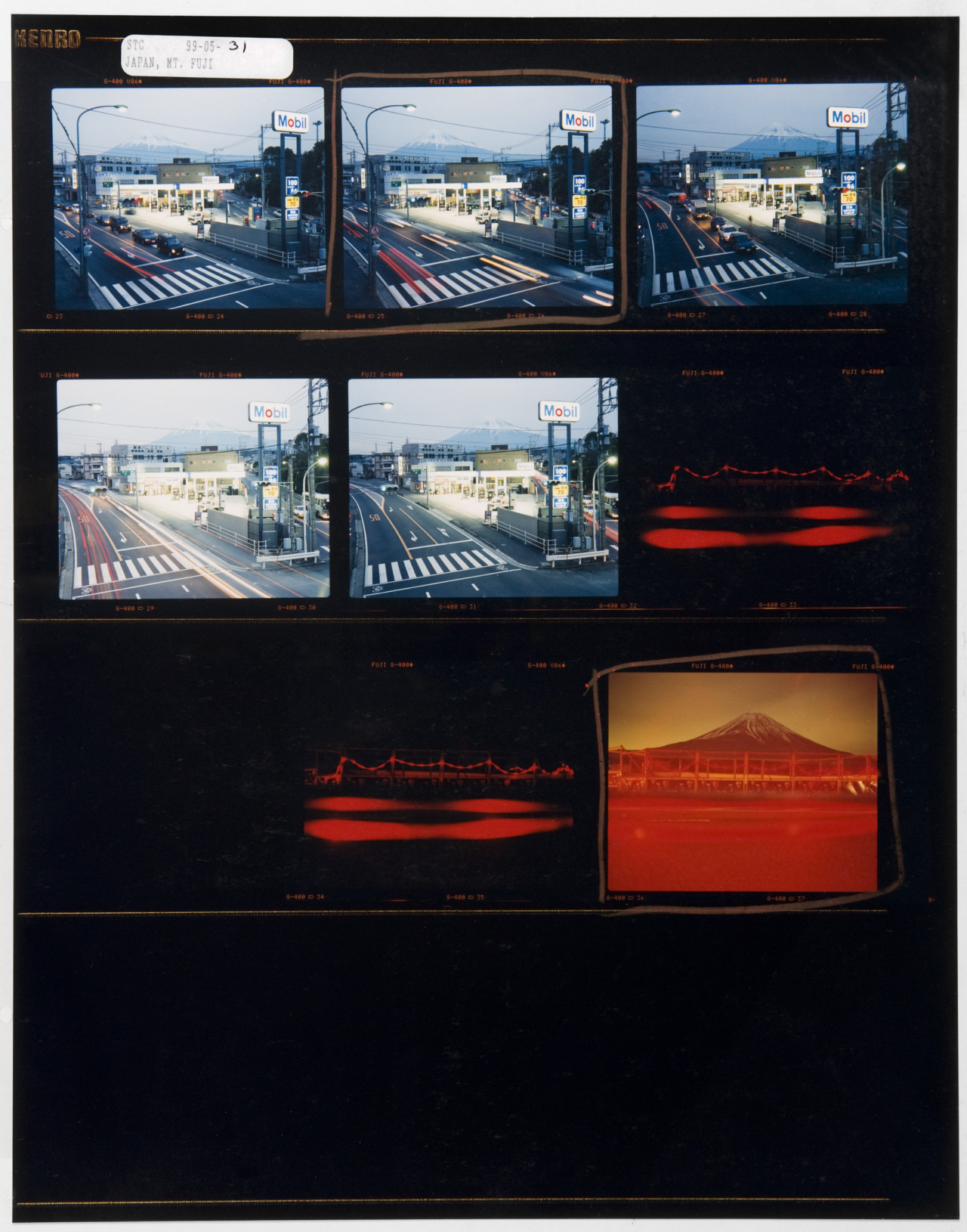

Contact sheets: direct prints of sequences of negatives were – in the pre-digital era – key for photographers to be able to see what they had captured on their rolls of film. They formed a central part of editing and indexing practices, and in themselves became revealing of photographers’ approaches: the subtle refinements of the frame, lighting and subject from photograph to photograph, tracing the image-maker’s progress toward the final composition that they ultimately saw as their best. There is a voyeuristic aspect to looking at a contact sheet also: one can retrace the photographer’s movements through time and space, tracking their eye’s smallest twitches from left to right as their attention is drawn. It is as if one were inside their head, offered a privileged view through their very eyes from the front row of their brain.

As Kristen Lubben wrote in her introduction to the book, Magnum Contact Sheets, first published in 2011 by Thames and Hudson:

“Unique to each photographer’s approach, the contact is a record of how an image was constructed. Was it a set-up, or a serendipitous encounter? Did the photographer notice a scene with potential and diligently work it through to arrive at a successful image, or was the fabled ‘decisive moment’ at play? The contact sheet, now rendered obsolete by digital photography, embodies much of the appeal of photography itself: the sense of time unfolding, a durable trace of movement through space, an apparent authentication of photography’s claims to transparent representation of reality.”

Here we look at the making of Chris Steele-Perkins‘ ‘Red Fuji’ image, which was to be used on the cover of his 2001 book Fuji: Images of Contemporary Japan. Both the image itself, and the contact sheet below are available on the Magnum Shop.

You can read other entries in Magnum’s series on contact sheets, and the making of iconic images here.

Fuji City, Japan, 1999

“The first images on this contact sheet are taken from a footbridge in a part of Fuji City where my wife’s father had a restaurant. My wife, Miyako, and I were having dinner with him that evening. The light was good when I shot from the bridge, so we decided to go back to Tokyo the long way round, in a big loop around Mount Fuji. At a certain point, Miyako pointed to the view we had of the mountain. It wasn’t terribly exciting until I came across some roadworks, and I knew I’d get something interesting from their flickering, artificial light. Because we were on a road and it was a long exposure, I had to jump in front of the camera with my coat open whenever cars drove past, in order to block out their lights. I basically guessed the exposures. The final one was about three minutes. People always ask if I used Photoshop, but I didn’t. The red is from the safety lights and the green from fluorescent lights in Fuji City behind the mountain. Two pictures from this roll of film made it into my Fuji book.

The idea for the project started when Miyako gave me a book of Hokusai’s prints, 36 Views of Mount Fuji. I was struck by the documentary nature of his images, which depict views of ordinary life, with the mountain as a presence in the background. The first view a foreigner usually gets of Fuji is on the bullet train out of Tokyo, when the mountain rises out of the surrounding industrial landscape. This is the unromantic reality, and yet in most photographic representations there is hardly any sign of human activity. I wanted to depict contemporary Japan in the shadow of Fuji as I really found it, and in so doing discover the country.

As the project progressed, I would get several rolls contacted together, from which I would then make proof prints of the images I liked. The contact sheet is interesting, as you carry in your head what you think you’ve photographed, but sometimes the actual picture doesn’t quite come up to scratch. On this sheet, for example, I didn’t realize that I’d messed up the exposures in the initial images of Fuji at the roadworks as much as I had done.

In Japan, ‘Red Fuji’ – meaning ‘Fuji tinged by evening light’ – is considered to be especially beautiful. People refer to this photo as my ‘Red Fuji’ picture, even though in the photo the mountain itself is not actually red. I like that apparent confusion, and this image ended up on the cover of my book, because it’s the sort of picture that you don’t interpret immediately; you look at it and wonder,

‘What is it? What’s going on?’ I want that. It’s ambiguous, and hopefully it draws people in.”