Making the Image: The Wall, by Raymond Depardon

The photographer explains the background of his image which captured the energy of a young punk's cry of "freedom, anger and pleasure" as the Berlin Wall came down

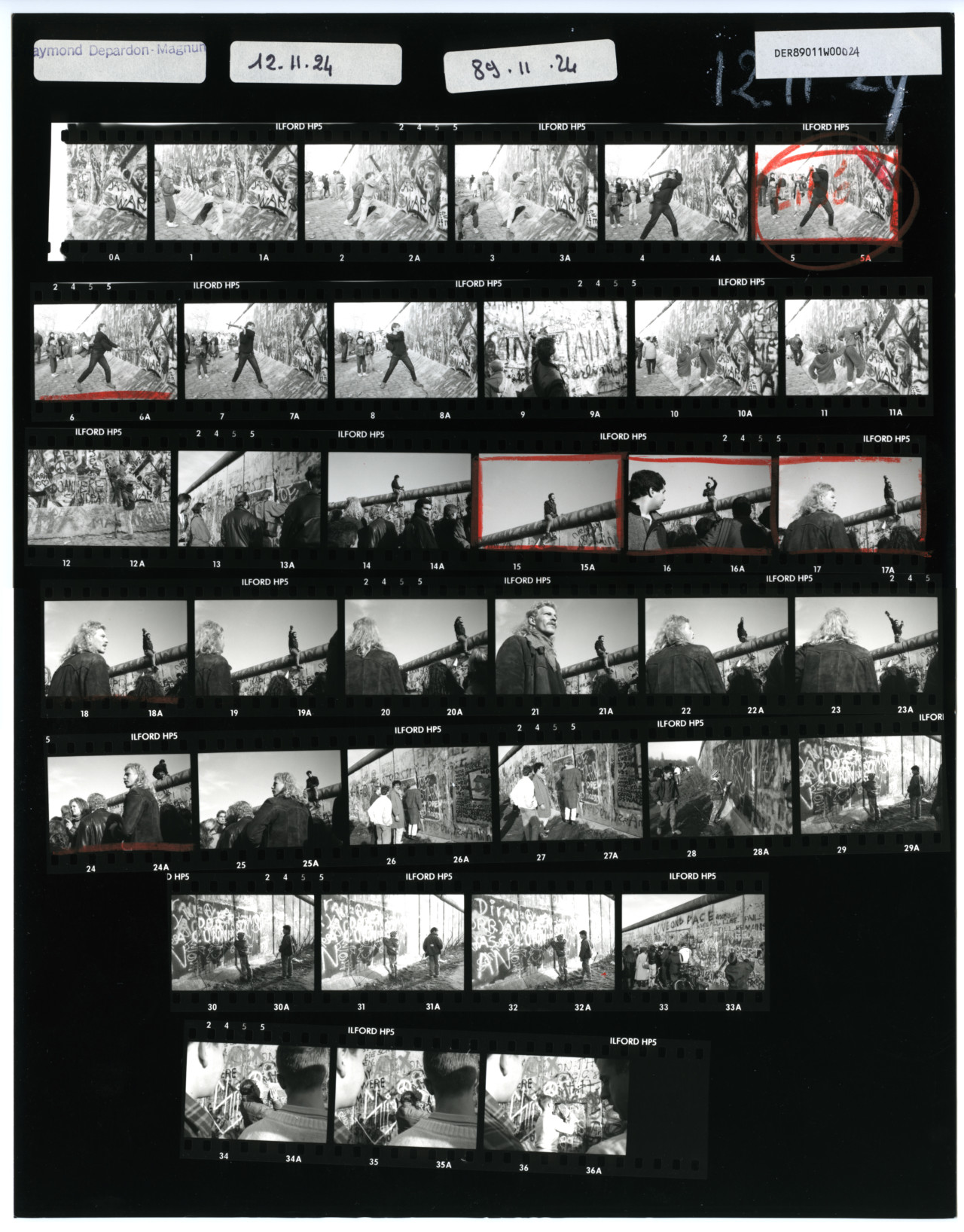

Contact sheets: direct prints of sequences of negatives were – in the pre-digital era – key for photographers to be able to see what they had captured on their rolls of film. They formed a central part of editing and indexing practices, and in themselves became revealing of photographers’ approaches: the subtle refinements of the frame, lighting and subject from photograph to photograph, tracing the image-maker’s progress toward the final composition that they ultimately saw as their best. There is a voyeuristic aspect to looking at a contact sheet also: one can retrace the photographer’s movements through time and space, tracking their eye’s smallest twitches from left to right as their attention is drawn. It is as if one were inside their head, offered a privileged view through their very eyes from the front row of their brain.

As Kristen Lubben wrote in her introduction to the book, Magnum Contact Sheets, first published in 2011 by Thames and Hudson:

“Unique to each photographer’s approach, the contact is a record of how an image was constructed. Was it a set-up, or a serendipitous encounter? Did the photographer notice a scene with potential and diligently work it through to arrive at a successful image, or was the fabled ‘decisive moment’ at play? The contact sheet, now rendered obsolete by digital photography, embodies much of the appeal of photography itself: the sense of time unfolding, a durable trace of movement through space, an apparent authentication of photography’s claims to transparent representation of reality.”

You can read other entries in Magnum’s series on contact sheets, and the making of iconic images here.

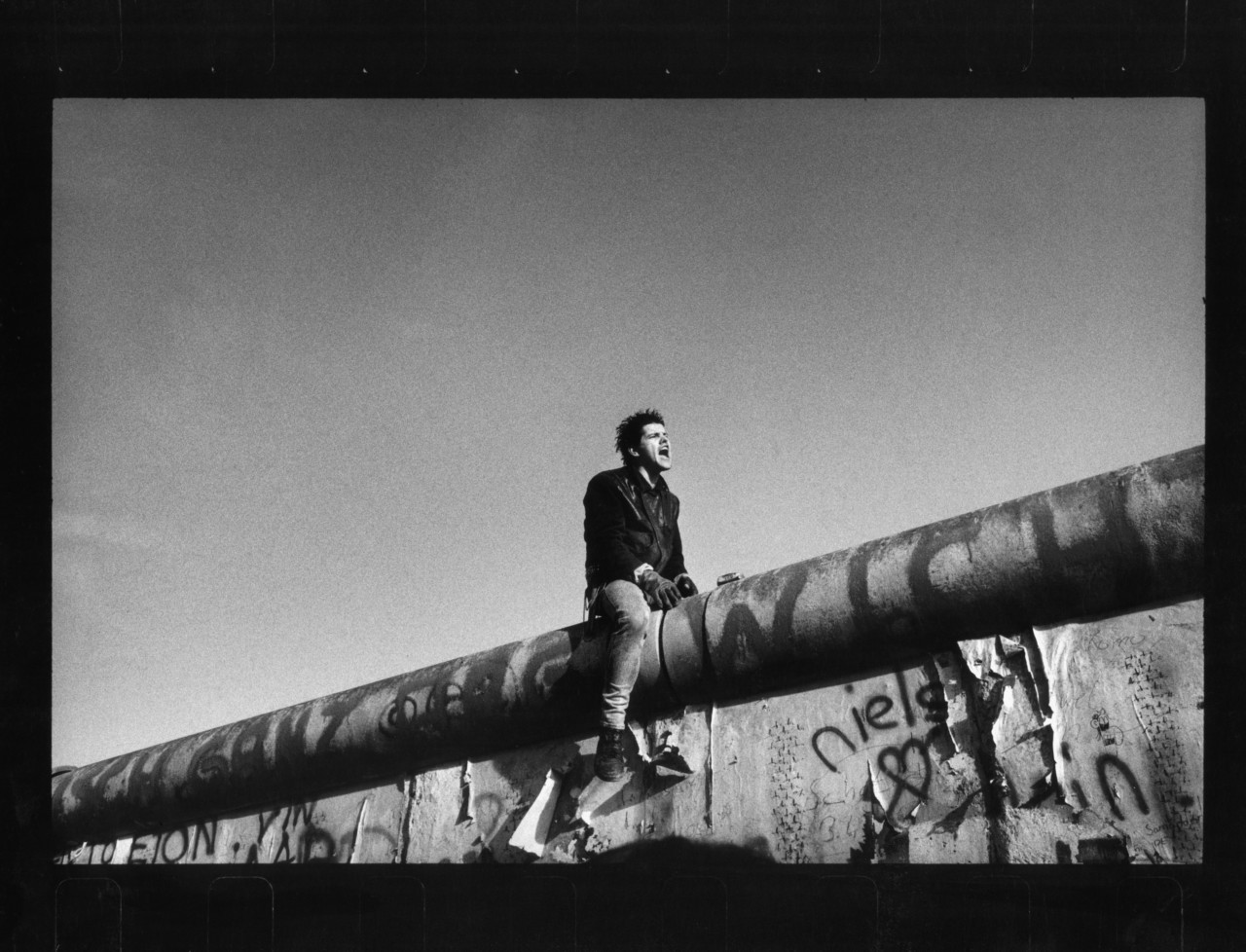

Having photographed the Berlin Wall being constructed as a 19-year-old, Raymond Depardon found himself back in the city – on assignment for the newspaper Libération – covering the Wall’s fall, in late 1989. He made the above image near the Brandenburg Gate, and while it featured on the front pages of the Financial Times, and Le Monde at the time it has, as he explains below, gained greater value over time.

Berlin, Germany, November 1989

“Back in 1961, when I was nineteen years old, I was sent to Berlin to take pictures of Robert Kennedy. It was at the time when the Berlin Wall was being constructed. I’ve therefore ended up covering its construction in 1961 and its deconstruction in 1989.

These pictures were taken in Berlin, at the Potsdamer Platz, near the Brandenburg Gate. Jean-Pierre Montagne, manager of the photo department at the newspaper Libération, had contacted me to tell me that the wall had fallen. He asked me to go there immediately to cover the event. Back then it was a ‘no man’s land’. The wall fell on the night of 9 November 1989, but all the photographers arrived on 10 November. The pictures of the young man on the wall were taken on 11 November. The wall had fallen, but not completely. Its symbolic remains were still there.

As you can see on the contact sheet, in the middle of the roll I started to focus on the young man on the wall. He was a punk from the West, and he suddenly screamed very loudly. That’s how he got my attention. He screamed and I grabbed my Leica and I shot. The power of the image is made by this rebel yell. It’s a cry of freedom, anger and pleasure. The scream symbolized the fall of the wall at the time. The picture appeared on the front page of the Financial Times and Le Monde, but it took a while before it became known as a good picture. I think it’s getting even more symbolic with time.

There are always pictures that we forget about, or don’t appreciate, or are disappointed by when we first see them. But, as time goes by, pictures become transformed. They gain in value, both sentimental and visual. I like to be on my own when I look at my contact sheets, because I’m often disappointed when I first look at them. For me it’s an intimate moment that I don’t like to share. But, as years go by, we become proud of our old contact sheets. They are a tool that allow us to fight against time.”