Manhattan Out

Raymond Depardon's unobtrusive photographing of New York's streets and inhabitants helped him overcome a period of creative inertia

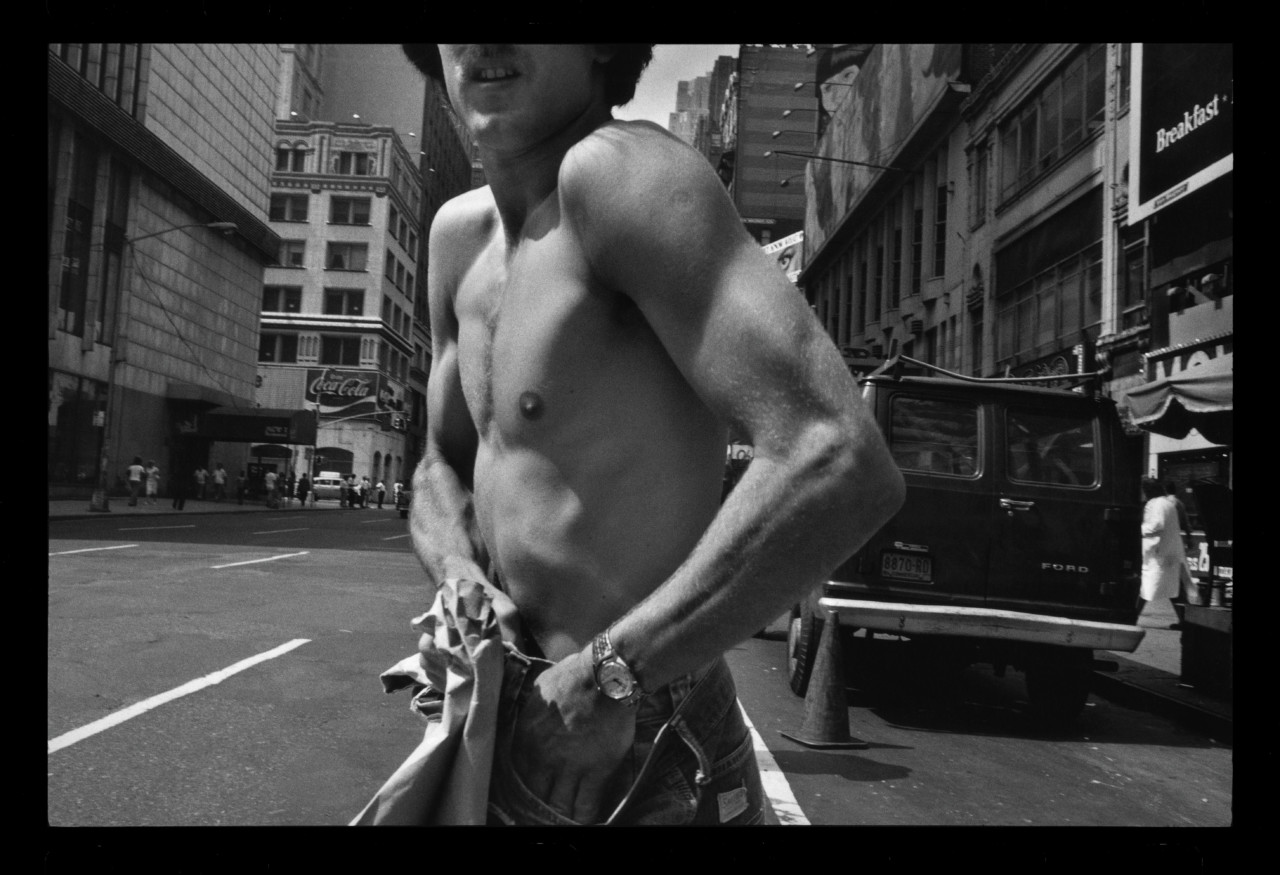

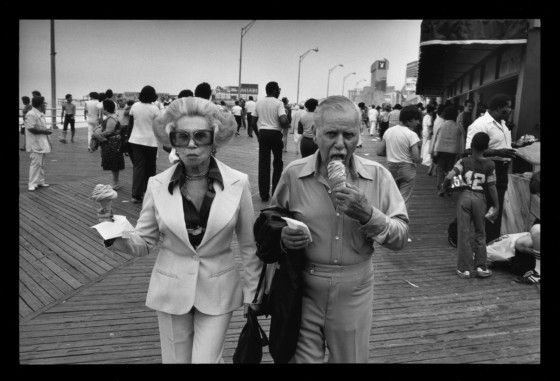

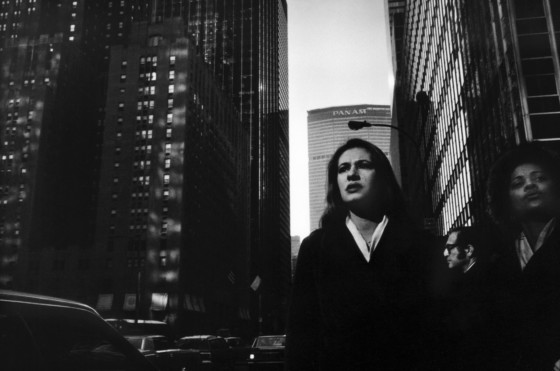

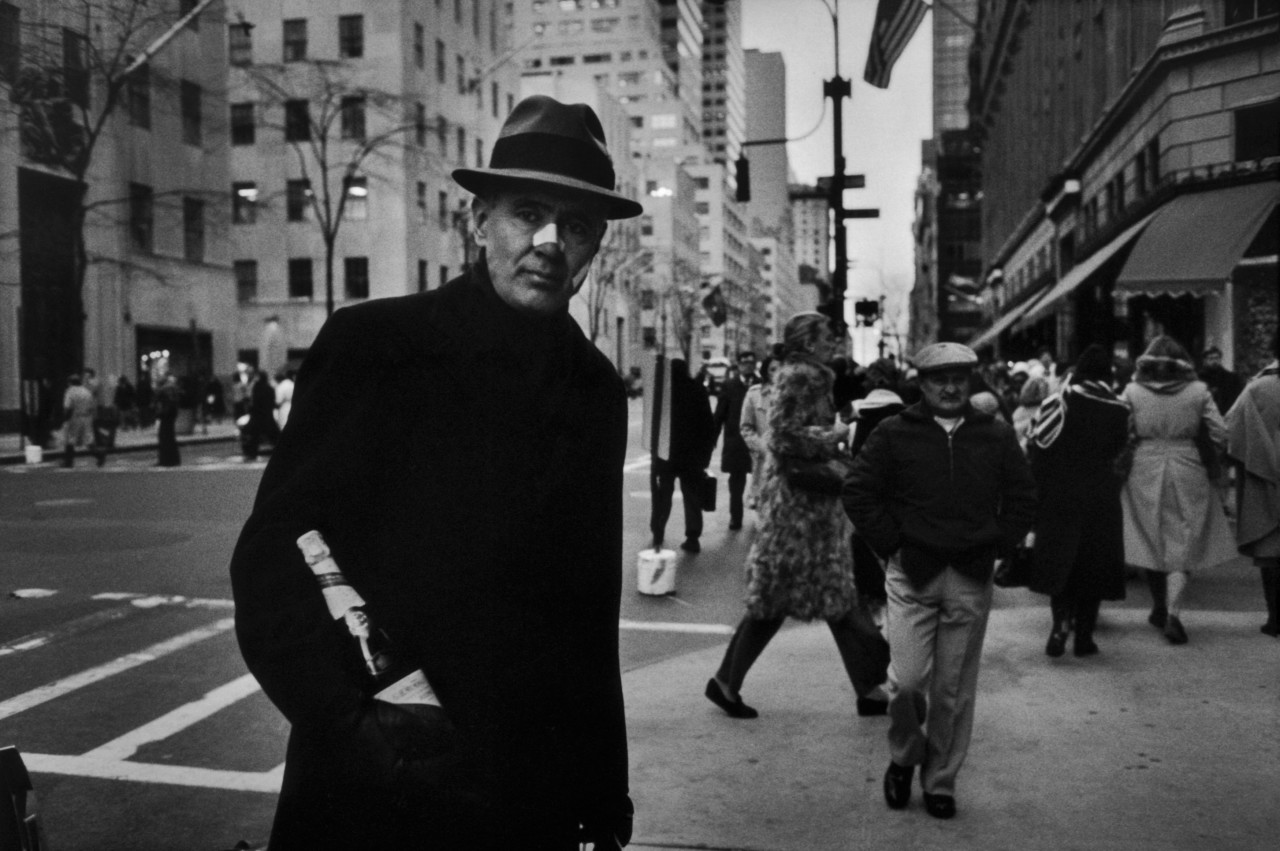

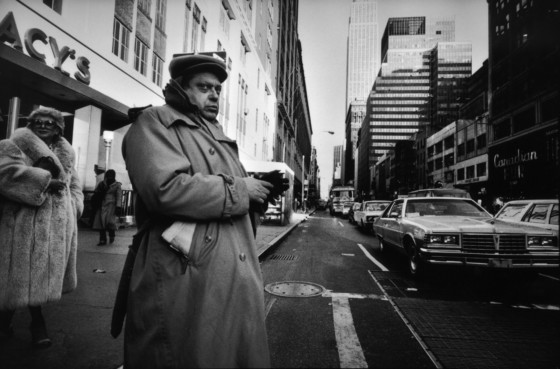

The photographs Raymond Depardon made in New York, over the winter of 1980, seem on first sight an anomaly within his wider work. The compositions are unusually chaotic, the focus somewhat haphazard, the lighting unpredictable. They convey a degree of the moodiness, closeness, bustle, and at times the seamy-ness of the midwinter streets of the city. It is only with the photographer’s own explanation of the context and mode of creating the work – only made public upon the printing of the Steidl photobook, Manhattan Out, in 2008 – that these puzzles start to be resolved…

Upon arriving in New York that year, Depardon had spent the preceding months in a psychiatric hospital near Trieste, Italy – a stay he describes as having lasted “a little too long”. Depardon had been there to resolve ‘personal confinement issues’ which he attributes to his two years in Chad reporting on the nation’s civil war, and the abduction of French archaeologist Françoise Claustre, work that won him a Pulitzer Prize.

The staff at the hospital had encouraged the photographer to use his camera as a tool to explore his relations with those around him and his confines, photographing other patients subtly, often without being noticed at all by his subjects, let alone arousing suspicion. As he put it, “I was gaining precious knowledge of the art of photographing others without intruding on them…”

He took that approach with him to America, and in an effort to reengage with taking photos applied it to the streets of New York. He spoke little English, was scared by the strangeness of Americans, and was alone – bar one friend who worked long hours. He filled his days shooting blind, from the chest, and for many months avoided even getting his rolls of film developed. Yet, as he explains below, the resulting work which he found so distasteful upon first seeing it performed a role in getting him back to work, “I was cured, I was no longer afraid of snapping away.”

Below, we share Depardon’s own explanation of the work.

"I found myself walking all day long, wandering the city from top to bottom"

- Raymond Depardon

When I came back from Chad in 1976, after two years spent covering the abduction of a French woman, I felt the need to exorcise some personal confinement issues with the help of a group of Italian psychiatrists who were revolutionizing the world of mental institutions with their ground-breaking program near Trieste. My stay at the madhouse off the Venetian coast lasted a little too long. I felt at home there. I was gaining precious knowledge of the art of photographing others without intruding on them – a necessary condition for anyone wandering those corridors and enclosed courtyards. I was learning how to move before such pain and muster the courage to document their suffering, to avoid it all sinking into oblivion in a general bout of amnesia. One of the psychiatrists encouraged me to come back and keep photographing his patients.

I arrived in New York in the winter of 1980 with a friend. She had just found a job there, and we decided to share a studio. She would leave at dawn and not return until late in the evening. I hardly knew anybody, so I found myself walking all day long, wandering the city from top to bottom.

"I would carry a Leica around with me, with that wonderful German-made M21 lens which had served me so well in Beirut, Afghanistan and Chad. It became my companion"

- Raymond Depardon

I soon found a way of quelling my loneliness. I would carry a Leica around with me, with that wonderful German-made M21 lens which had served me so well in Beirut, Afghanistan and Chad. It became my companion, my alibi against that feeling of guilt born from having nothing else to do. I was terrified of Americans – maybe because I did not speak their language – although I was familiar with their photographers, their movies, their music. They frightened me… more so than the hostage-takers in Tibesti or the loonies in Venice. I soon learned to dress like a courier, wearing a huge parka and woolly hood. I became one of theirs.

"Sometimes I would stop for a short break. I would buy a French newspaper and bask in the warmth of a coffee shop, or walk up a flight of stairs to a photo gallery and let those wonderful silver images recharge my batteries"

- Raymond Depardon

I did my best to blend in. I walked fast; I knew the city like the back of my hand. I would brush past people in the street without even noticing them. I decided as a rule never to lift the camera to my face, leaving it to dangle on my chest. My body would perform the tracking shots, like a filmmaker without a camera. I just keep walking… sometimes I would stop for a short break. I would buy a French newspaper and bask in the warmth of a coffee shop, or walk up a flight of stairs to a photo gallery and let those wonderful silver images recharge my batteries. When I stepped out again I was fully charged, with memories of the desert, or of my childhood days on the farm, dancing around in my head. I loved Wall Street with its hustle and bustle. The women there always seemed to wear a frown. Smiling was scarce during lunch-break and non-existent before or after office hours. I was fresh back from Peshawar and was fully aware of how different the two cities were. How could I not be. In Peshawar, everybody has their nose in other people’s business. If you are buying an item on a market stall, people will step in to give you advice or share their opinion with you. Passers-by, the person standing next to you. Everybody. New York is the opposite. As long as you abide by the prevailing fake indifference, you can get away with anything. Nobody will take a moment to talk to their neighbor. No one cares about the photographer as long as he goes by quickly. No one looks at him… but everyone sees him. American women do not like to be stared at, but the same is true in Peshawar.

"My fear would not go away. Why would it? After all, I did not talk to anybody. I was in the most tolerant city in the world, and still I was afraid of taking that next photo"

- Raymond Depardon

My fear would not go away. Why would it? After all, I did not talk to anybody. I was in the most tolerant city in the world, and still I was afraid of taking that next photo. If I bumped into a famous photographer from Magnum, I would hide my camera, hoping to avoid questions.

I spoke to no one about my photos. It took me a few months to actually pluck up the courage to have them developed. I came back to France for a while, I had rented my apartment out, so I stayed in a box-room at the Magnum office in Paris. I soon returned to New York and hit the sidewalks once again. The light had changed. My friend and I ventured upstate for the weekend. She wondered why I kept taking all those photos. I did not answer. She ignored the photographs.

I hated them when I finally saw them for the first time. The composition was wrong. So was this. So was that… later I started working on a film called New York, N.Y., a ten-minute short made of three shots. I also worked as a correspondent for the French daily Libération all summer. I was cured, I was no longer afraid of snapping away. And that was the end of it.

I forgot about those photos for twenty-seven years. I did not have any good-quality prints, and it was not until a few months ago that I finally had them blown up and showed them to a friend. It is interesting to realize that most Americans I captured on photos were looking at the lens and were therefore aware of their picture being taken. I was convinced at the time that I had them fooled.

New York is a city you always go back to. Since 9-11, it has become less complacent with wandering photographers like myself. The photogenic element is still there. But perhaps it has moved to Tokyo, the new capital of indifference to foreigners.