Mexico Retold

Jerome Sessini returns to the city where he first became a photographer, and is guided only by instinct and deep emotion

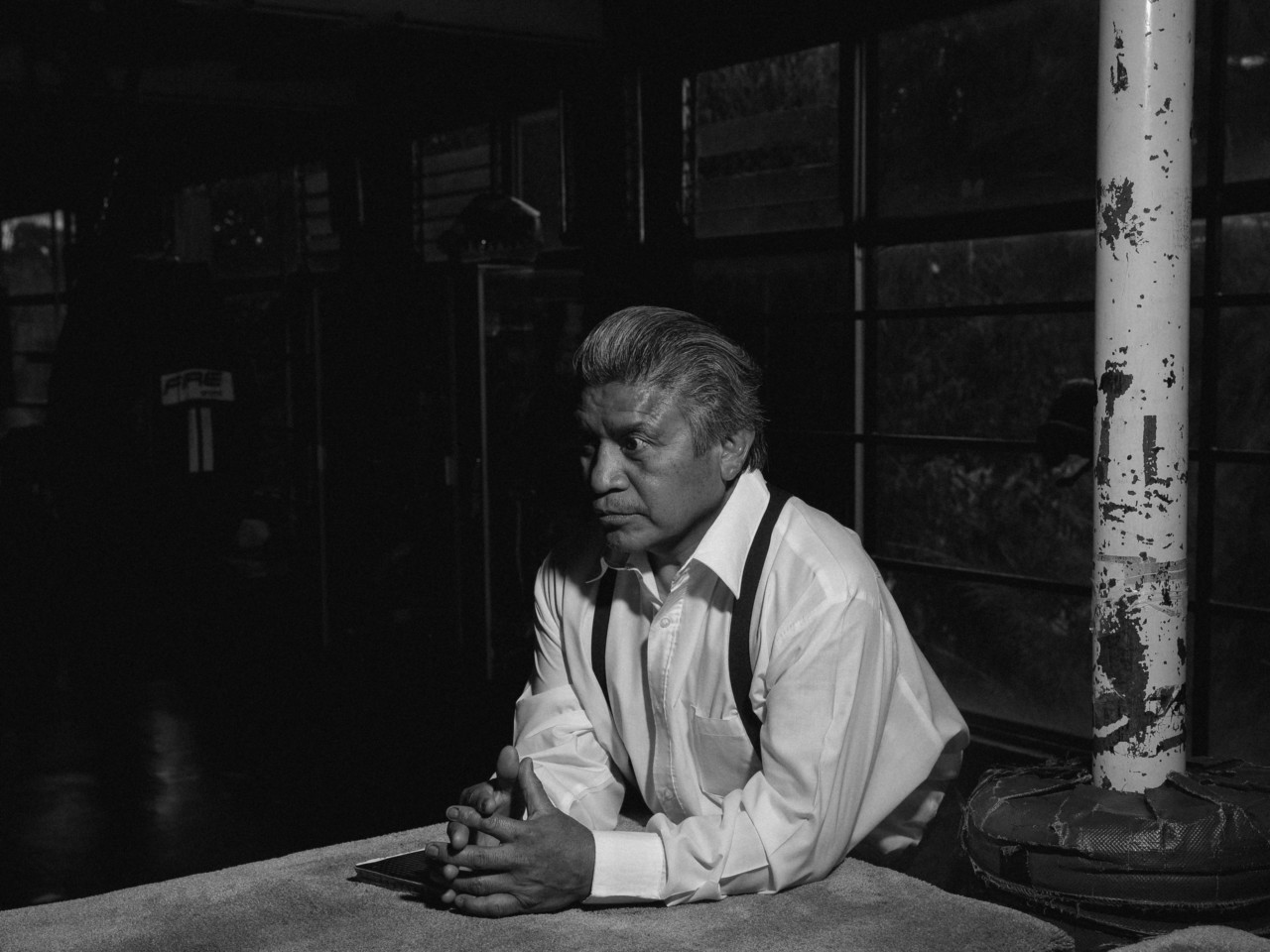

Returning six years after publishing his book on Mexico’s drug war, The Wrong Side: Living on the Mexican Border, and over 20 years after he first visited, Jerome Sessini’s new project Mexico Retold explores the photographer’s connection to the country using a more lyrical approach, represented by black and white portraiture and architectural photography. Here the photographer discusses how the project came together, including the influence of boxing, Henri Cartier-Bressson, and an emotional approach to image-making.

When did your journey with Mexico City begin?

Mexico City is a long story for me. I went there for the first time in the mid ‘90s and it is where I decided to become a photographer. I don’t know why but it always fascinated me; the mystery, the images by Cartier-Bresson of course, the boxing.

The atmosphere of Mexico City also impacted me a lot. It’s in a valley surrounded by volcanoes and there’s a strange mix of Aztec culture, pre-Hispanic culture, Surrealism, modernity…I feel an attraction to it and at the same time I’m scared of it.

Why did you decide to return to Mexico City in 2018 and 2019 and what did you want to explore in particular?

The previous visits were more journalistic, it was documentary work and always based on important events, especially between 2008 to 2012 when I was documenting the political situation and the narco violence. This time it was about my impressions, not related to any event. I was trying to work based on my emotions towards the city and less on a journalistic point of view. There was no pressure but at the same it was more difficult because you have to find something more deep in your emotions.

This project contrasts quite dramatically to how Mexico is often portrayed; the Day of the Dead, brash colours, a sense of aliveness. Your work here is marked by the shadows and the empty space, you have left a lot of room for interpretation.

The work of Cartier-Bresson was a great inspiration to me. The first series by him in Mexico [in 1934] is the best work he ever produced I think. It has more light and dark than the work he produced after, it’s less perfect but it’s much more poetic and there is more mystery. He was young, and made some of his first steps aboad as a photographer in Mexico. I did too.

I had some of his pictures in my mind during this project. The difficulty was not to repeat Catier-Bresson but to simply keep some images in my mind; and recall the sense of darkness. But there is one picture—a lady dressed in black holding a baby—that I was obsessed with and was the starting point for the whole project. That’s the only one I really wanted to remake. I took this picture of a young single mother holding a baby [at a Chilango Low Rider’s party] and I think this is the modern version of Cartier Bresson’s photo.

You have a personal connection to Mexico City?

I have family in Mexico, I met my wife almost 20 years ago in Mexico City. That is why I have a very special relationship with the country; I can really see the society from inside. My wife’s family are middle class, they are a big family; she has nine brothers and sisters. Every time I go there, something has happened—problems with work, problems from people running rackets for the cartel. It’s very common in Mexico, every single person has had to pay something to the cartel, rich or poor.

San Judas day, which you documented for this project, seems to show a sense of the collective spirit of that particular social strata, in the face of adversity, was that evident to you?

Yes. It is only the middle and lower classes who attend this tradition, they all come from the same area. The upper class people would not be part of it – for them it’s like an exotic country. They’re afraid of the danger. And in parts it is very dangerous – for example in the Tepito neighborhood I can’t go there at night and when I’m there during the day I have to go with someone from the area.

The project includes color images among the majority, which are black and white.

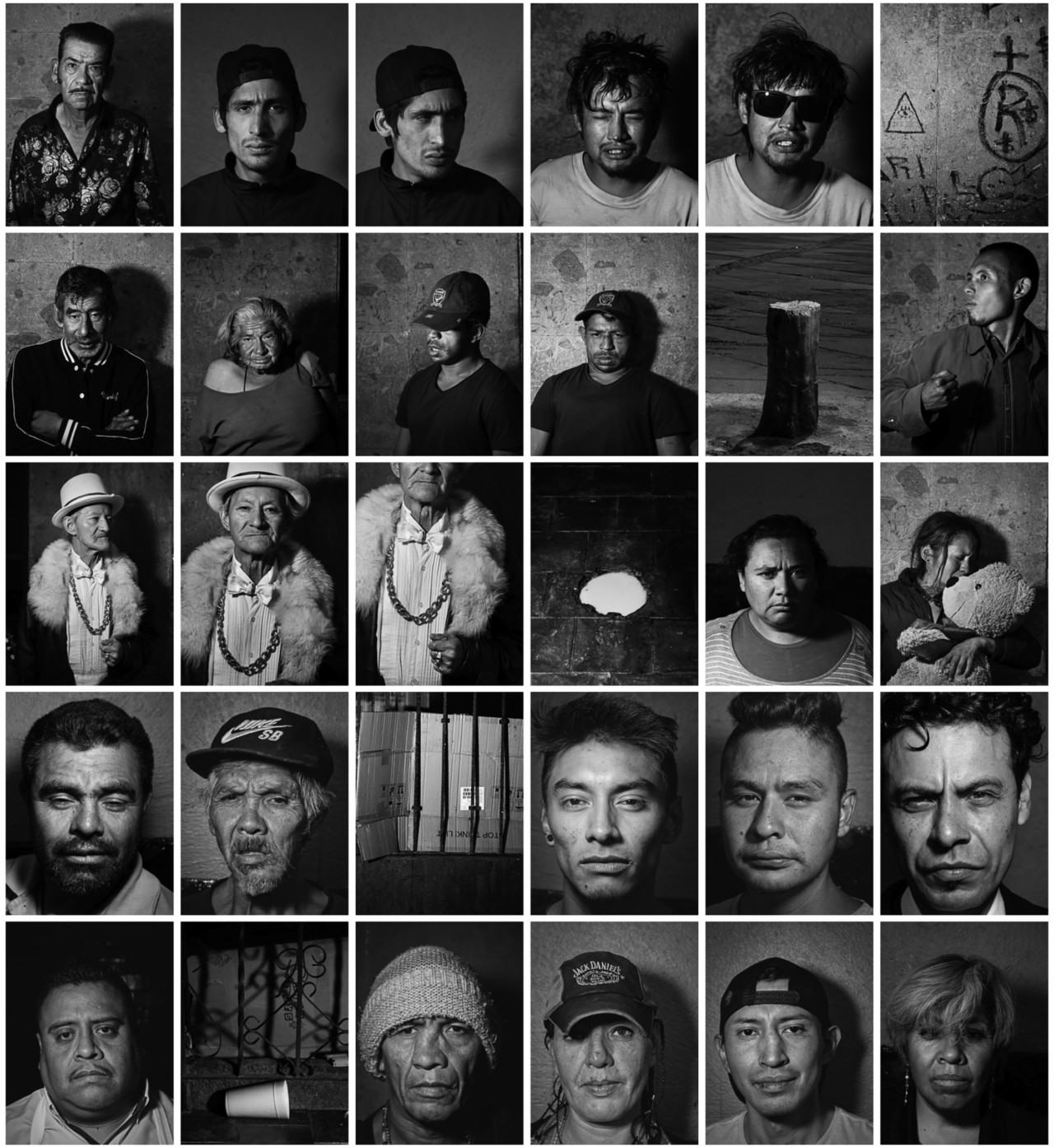

Talk me through the grid portrait, what do you think it reveals about the city?

It was a way to approach the city by just showing the faces. The faces tell a lot about the place and the atmosphere. When I made the portraits I wanted them to be all done in the same place, Plaza Garibaldi. I wanted the same background, same light, and really focus on the faces and their expression.

It’s an interesting parallel to the grids of the city. There’s the blankness of the buildings, only the cold architecture, and then the faces with their context removed…

Yes, and I’m trying more and more in my photography not to be totally exhaustive but only to make portraits and landscapes.

The portraits in Plaza Garibaldi remind me of the portraits from your opioid series in America, in the fact that although these people have a difficult situation in life, there is still a depth and humanity that is revealed – the photos are beautifully lit and the people are removed from the context of their situation, it doesn’t define them.

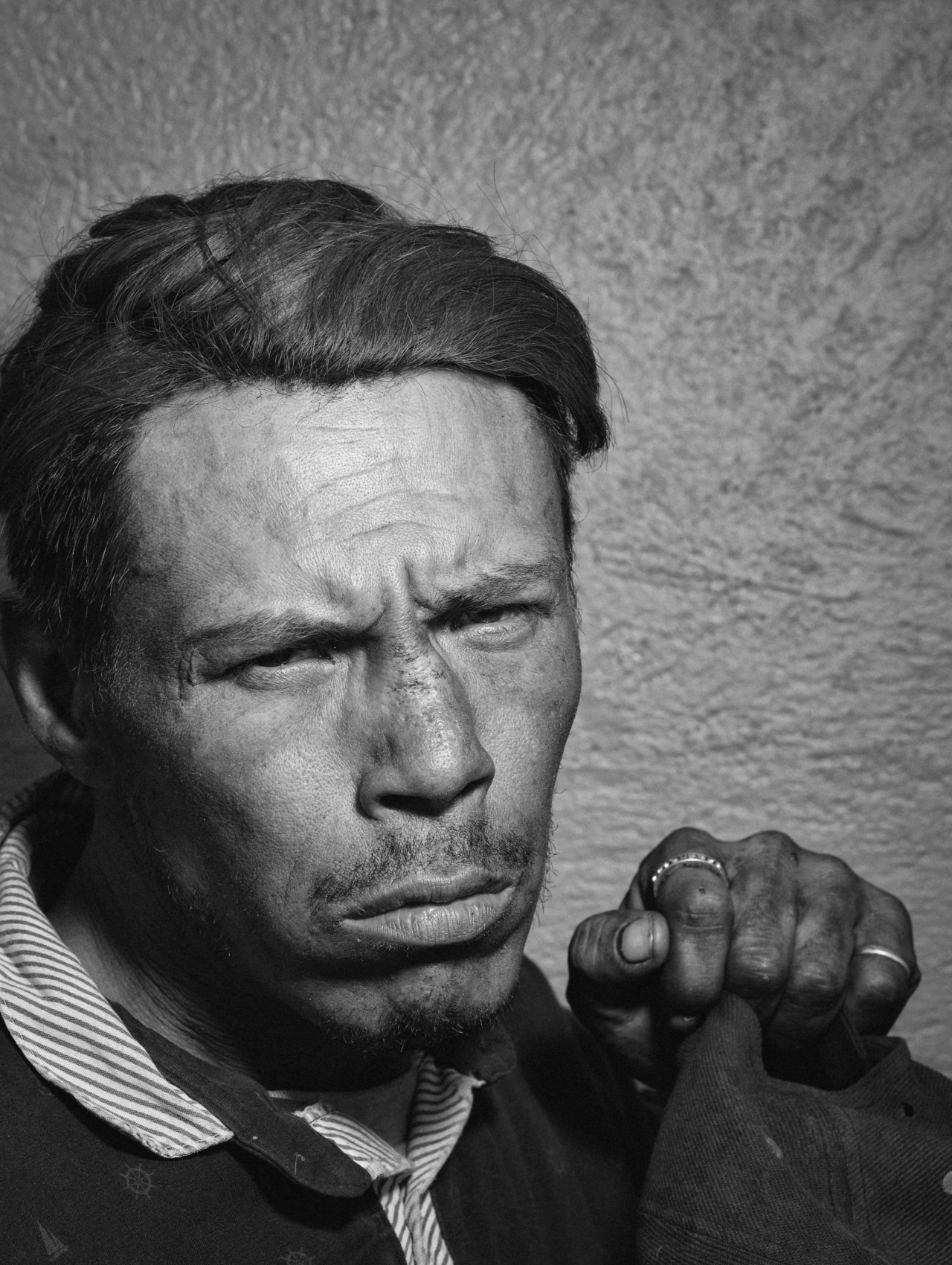

I’m always interested in people who are on the edge. They are discriminated against because of the life they chose or because of the difficult situation they are in, but when I photograph them I don’t see their social condition, I just photograph who they are as a person and I try to remove the context and all the reasons why they’re discriminated against and look for something more universal.

Someone said to me: Why do you always photograph the poor people and not the rich people? But it’s my view that with photography you have to choose what you want to show, you cannot be exhaustive because then it becomes something different. You have to choose a vision and approach and hopefully this can leave space to the audience to imagine.

This seems to be the approach you took when photographing the migrant caravan; the individual narratives are front and centre not the huge numbers of people. Why was it important to highlight the individual rather than the collective?

I tried to take the people out of the context and photograph their personality. I usually photograph the Mexican people going as migrants to the north and this was the first time that I saw Mexican people welcoming migrants from South America, so for me it was very interesting to photograph that situation.

One of your first projects in Mexico was about the boxing culture there. Why did you decide to return to this subject again now?

It was very important to photograph boxers in this photo essay because it’s the main sport in Mexico. The Mexican boxers have a particular style, Russian and Americans claim to box like Mexicans, which means very aggressive, only going forward never backing off. It very much represents the Mexican mentality; life is a struggle.

There is a long story here of violence, and since 2008 it has been getting worse every year. Fifteen years ago it was located in the north of the country on the border and it’s now all over the country, even in Mexico City , there is a drug cartel operating.

There seems to be an interesting parallel between the violence that the people don’t invite—that’s propagated by the cartel— and the violence that they do invite, through the sport of boxing.

Well most of the young people learn the violence from the street—crime, selling drugs; this is all part of the sport. Also the history; the ancestors of the Mexicans, the Aztecs, were the most violent culture in Mexico and this still exists in the street culture.