Photographing a Crisis

A guide through the ethics and considerations of documenting the migrant crisis

Magnum Photographers

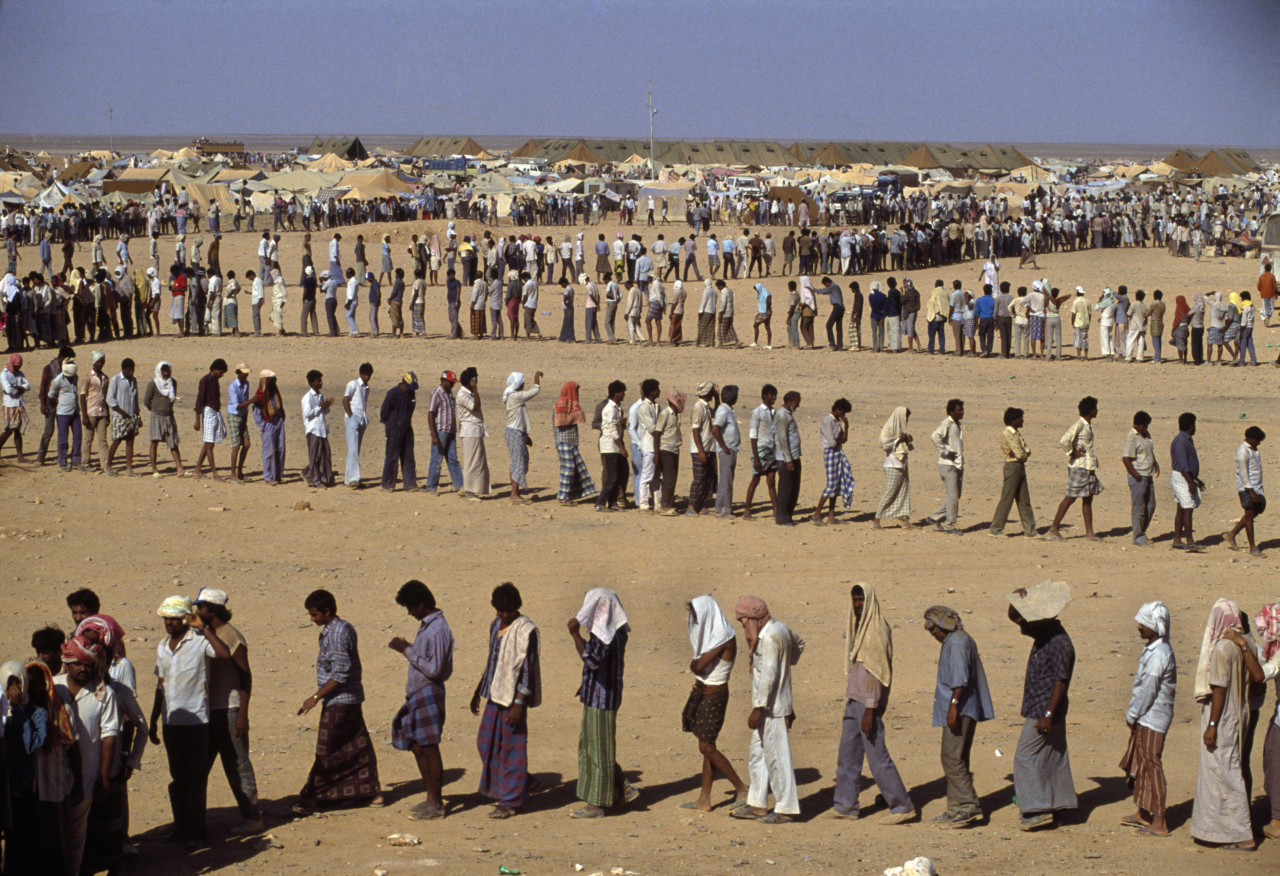

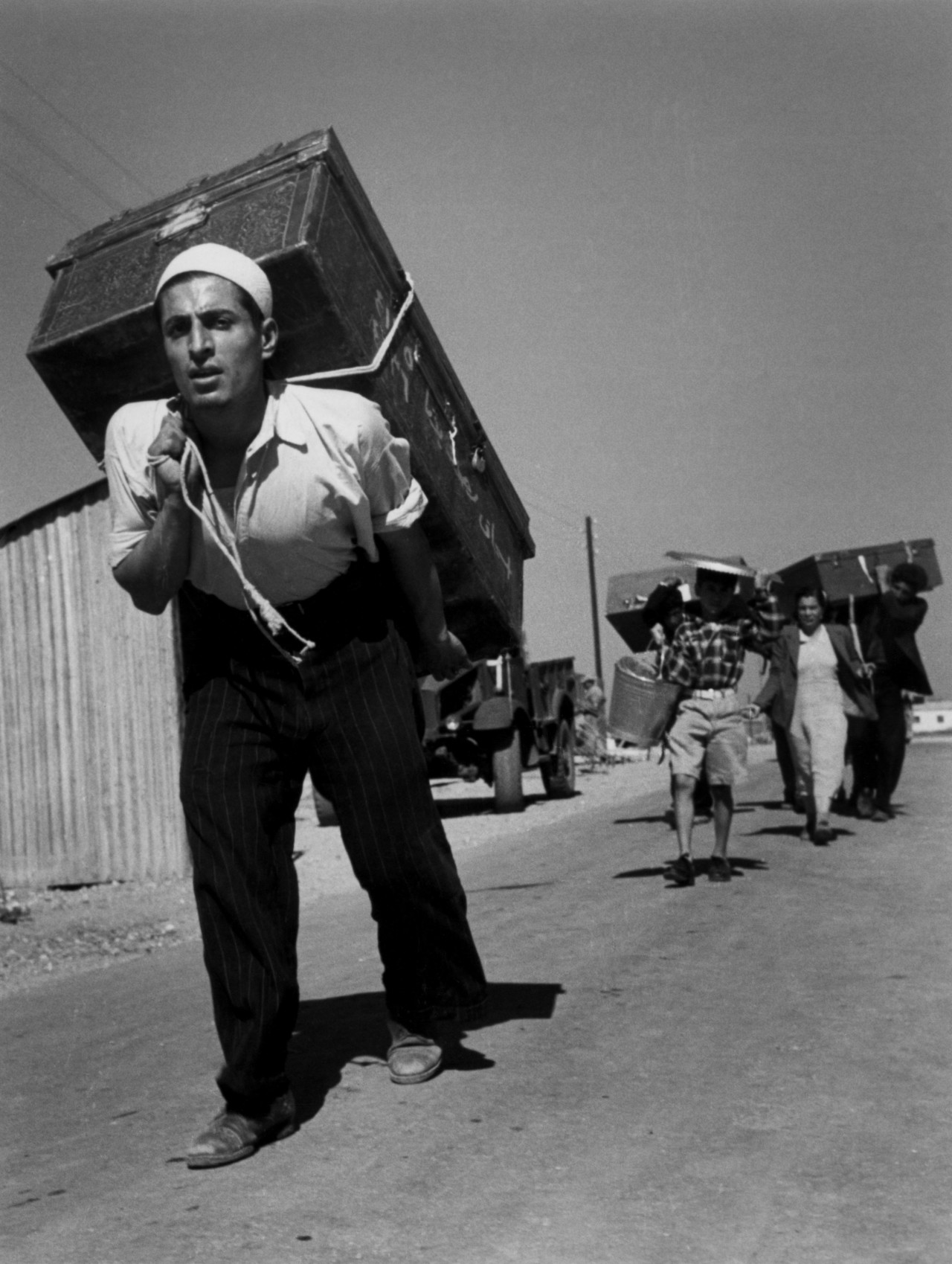

Magnum’s coverage of the movement of displaced people stretches back to the post-war Europe captured by Magnum founders Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger and David ‘Chim’ Seymour, and goes right up to the present day. The world is currently experiencing the largest movement of people since World War II, with recent figures from the UN stating that 65.3 million people, or one person in 113, were displaced from their homes by conflict and persecution in 2015. These kinds of figures and the myriad individuals with stories that make them up have spurred Magnum to once again explore migration.

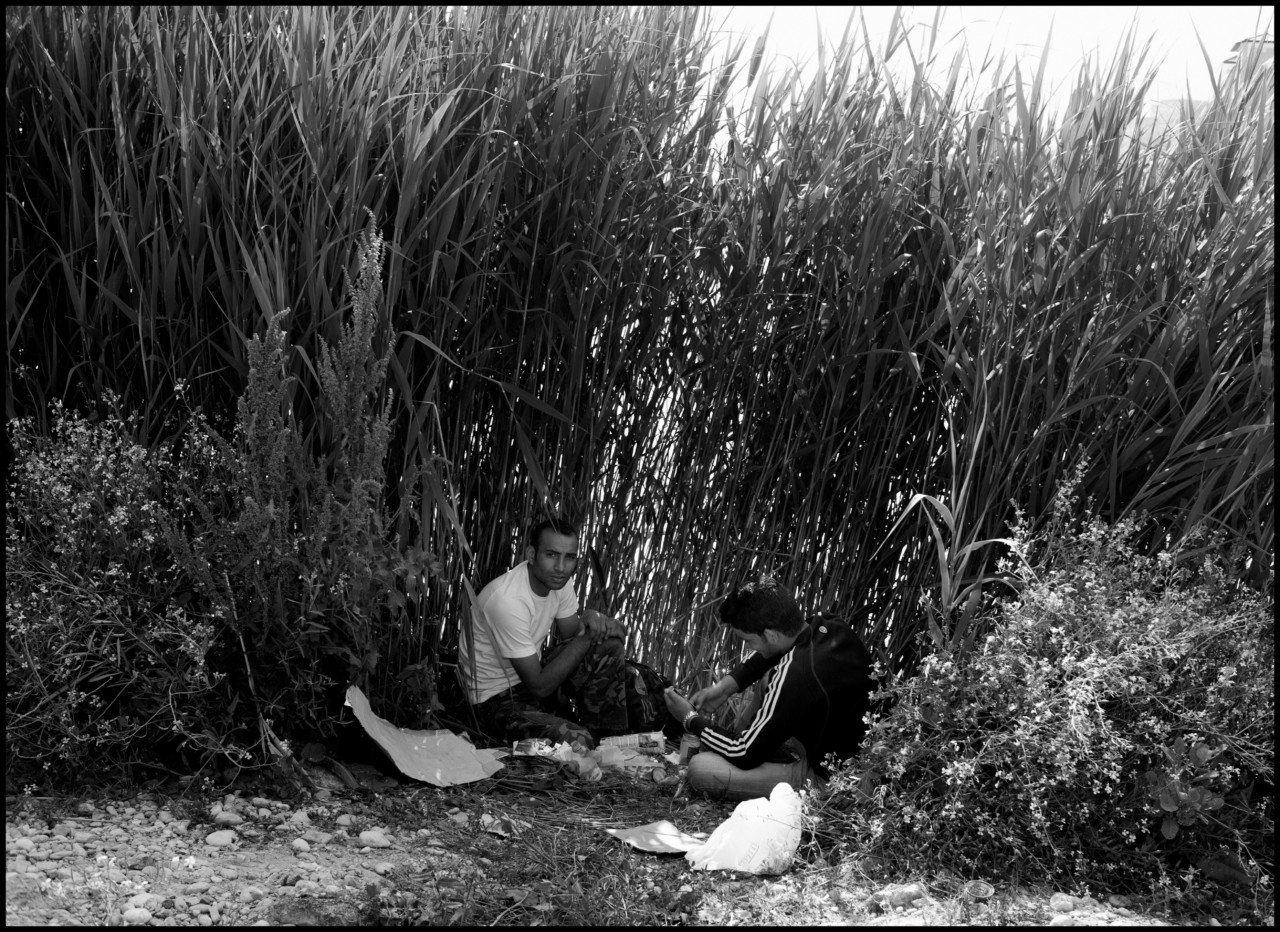

This recent work includes Paolo Pellegrin’s ‘Desperate Crossings’ series, Jérôme Sessini’s studies of the Calais Jungle, Alex Majoli’s documenting of the refugee crisis in Greece and Africa, Mark Power’s explorations of refugee camps, and Matt Black’s tracing of aid from depot to drop-off point. “We have a responsibility to think not just about what’s going in one particular place at one particular time; it is very important to capture as many ends of this story as possible,” says Magnum’s Executive Director David Kogan.

In the first of a series of talks spanning Magnum’s 70th year, The Barbican, London hosted a panel where key players in the documentation of migration photography discussed issues affecting them, from the motivation to shoot migration to the practical and ethical concerns that come with capturing it. Here, we present some of the thinking that surrounds the documentation of the migrant crisis.

A Duty to Record

In the face of human suffering, being equipped with nothing but a camera can leave a photographer feeling “helpless” – the word of Magnum’s Mark Power, who photographed the Azraq and Zaatari refugee camps in Jordan in 2015. But Power, photographers like him, and the agencies who commission them, are driven by a sense of duty, not only to tell the human story but to create an historical record. “I believe strongly in photography as a mark of history to carry forward to future generations to learn from,” says Power. “Marking history for the future is very much part of my agenda so I try to be as objective as one can be in a situation like that.”

The Power of the Single, Still Image

While footage from European borders or inside refugee camps is beamed into television screens with such regularity that there is a danger of it inducing compassion fatigue, the still photograph is a pause point. It presents a moment to stop and consider. The people in the photograph cannot walk out of shot, out of focus and out of the viewers mind, but are preserved in a visual document. “The images later become artefacts; they come to hold some sort of power,” says David Kogan.

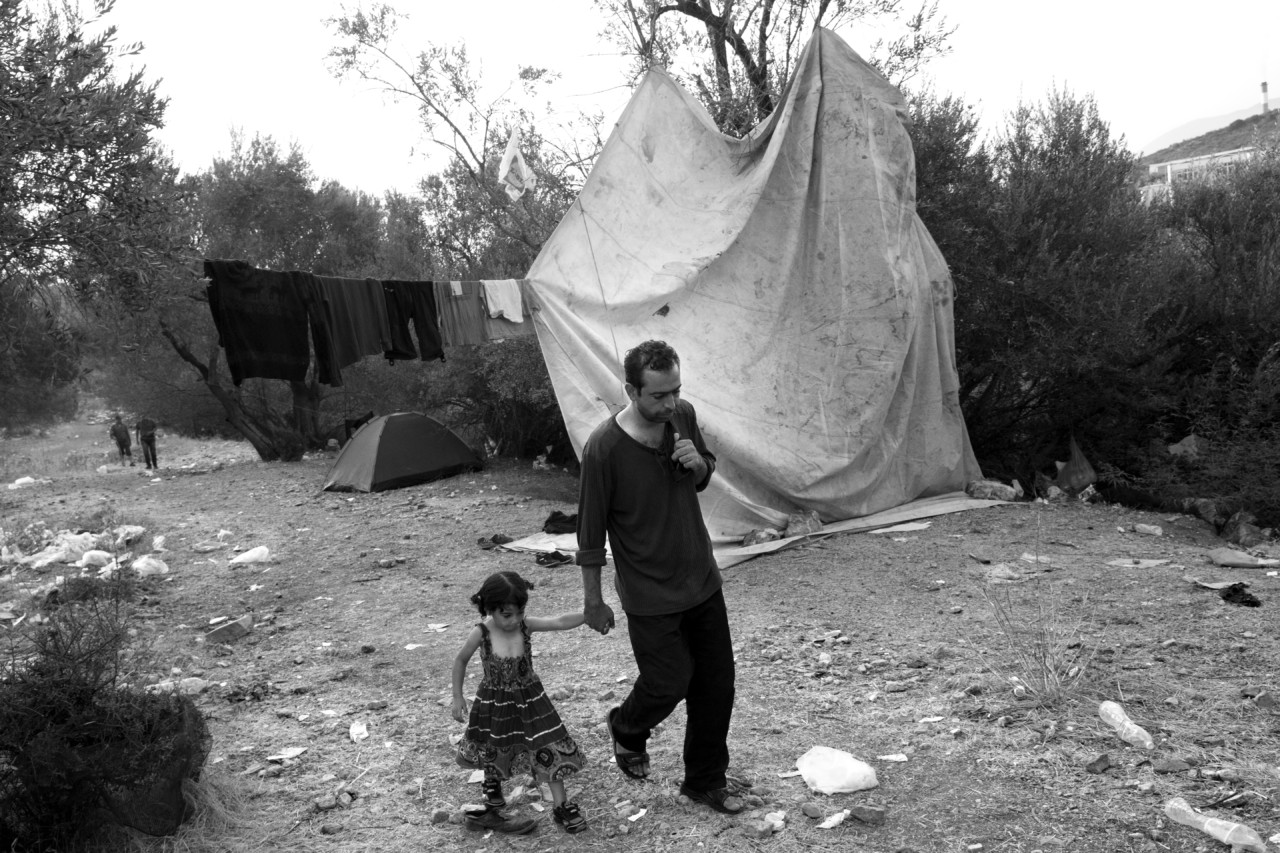

Dignity and Consent

Amnesty’s Steve Symonds says that respect for the individual depicted in the image should be a key concern for both the photographer at the point of taking the photograph and for the editors and media companies who might eventually make use of it: “We’re very cautious at Amnesty to avoid the use of images where we think people – dead or alive – are robbed of their agency and presented merely as victims. It becomes extremely difficult to engage with someone about what the consequences of giving their image or story might be before they have got to a destination, before they have resolved the circumstance that has driven them to be on the move.”

Safety of the Subject

While the benefits of telling the stories of migrants through photography may be to enhance public understanding, empathy and perhaps even effect policy change, the publication of the images can carry a risk for those depicted. For instance, many of the people Amnesty International talks to have families elsewhere, often back in the countries from which they have fled, facing the same risks from which they are fleeing. Using images of these people in campaigns or press may put these family members in danger.

The organizations publishing this material must also be aware of the particular message their use of it gives. For Amnesty, this puts images published by them within the context of their prominent position as a campaigner of human rights. “We are heavily associated with countries like Afghanistan, Syria and Eritrea. We are strong advocates against human rights abuses and therefore being too publically associated with individual people who may have family back home is potentially is a risk for family members,” explains Amnesty’s Steve Symonds.

Read about more discussions from the Magnum Photos Now events here.